Vertigo

Horizontal nystagmus, a sign which can accompany vertigo. | |

|---|---|

| ICD-10 | A88.1, H81, R42, T75.2 |

| ICD-O: | |

| ICD-9 | 078.81, 386, 780.4 |

| OMIM | [1] |

| MedlinePlus | [2] |

| eMedicine | / |

| DiseasesDB | 29286 |

Vertigo is a specific type of dizziness where the individual has a sensation that his or her body is spinning, or that the environment is spinning around the body, even though there is no movement. This illusion of movement is a major symptom of a balance disorder.

There are two basic types of vertigo: subjective and objective. Subjective vertigo is when a person feels a false sensation of movement. Objective vertigo is when the surroundings will appear to move past a person's field of vision.

The effects of vertigo may be slight. It can cause nausea and vomiting and, if severe, may give rise to difficulty in maintaining equilibrium, including difficulty with standing and walking. The causes of vertigo also can be minor, such as cases of actual spinning from a playground carousel, or can suggest more serious problems (drug toxicities, strokes, tumors, infection and inflammation of the inner ear, cerebral hemorrhage, etc.). In these cases, the onset of vertigo can serve a useful purpose in alerting a person to a possible underlying condition.

The word "vertigo" comes from the Latin verter, meaning "to turn" and the suffix -igo, meaning "a condition"; in other words, a condition of turning about (Merriam-Webster 2007).

Causes of vertigo

| Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo Classification and external resources | |

| Exterior of labyrinth. | |

| ICD-10 | H81.1 |

| ICD-9 | 386.11 |

| OMIM | 193007 |

| DiseasesDB | 1344 |

| eMedicine | ent/761  emerg/57 neuro/411 |

| MeSH | D014717 |

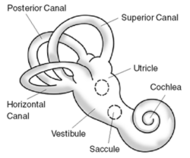

Vertigo is usually associated with a problem in the inner ear, or in the brain, or with the nerve connections between these two organs.

The most common cause of vertigo is benign paroxysmal positional vertigo or BPPV (Bellot and Mikhail 2005). This is characterized by the initiation of the sensation of motion by sudden head movements. Another cause is labyrinthitis‚ÄĒinflammation within the inner ear. This is usually associated with sudden onset of vertigo (Bellot and Mikhail 2005).

Other causes include meniere disease, acoustic neuroma (type of tumor), decreased blood flow to the brain and base of the brain, multiple sclerosis, head trauma or neck injury, and migraine (Bellot and Mikhail 2005). Vertigo can be brought on suddenly through various actions or incidents, such as skull fractures or brain trauma, sudden changes of blood pressure, or as a symptom of motion sickness while sailing, riding amusement rides, airplanes, or in a motor vehicle.

The onset of vertigo can be a symptom of an underlying harmless cause, such as cases of actual spinning, like the BPPV experienced from amusement rides. In such cases, vertigo is natural given that the fluid in the inner ear continues to spin although the body has stopped, among other factors. In other cases, vertigo can suggest more serious problems, such as drug toxicities (specifically gentamicin), strokes, or tumors (though these are much less common than BPPV). Vertigo can be a symptom of an inner ear infection. Bleeding into the back of the brain (cerebellar hemorrhage) is characterized by vertigo, among other symptoms (Bellot and Mikhail 2005).

Vertigo-like symptoms may also appear as paraneoplastic syndrome (PNS) in the form of opsoclonus myoclonus syndrome, a multi-faceted neurological disorder associated with many forms of incipient cancer lesions or virus. If conventional therapies fail, the patient should consult with a neuro-oncologist familiar with PNS.

Vertigo is typically classified into one of two categories depending on the location of the damaged vestibular pathway. These are peripheral or central vertigo. Each category has a distinct set of characteristics and associated findings.

Vertigo in context with the cervical spine

According to chiropractors, ligamental injuries of the upper cervical spine can result in head-neck-joint instabilities that can cause vertigo. In this view, instabilities of the head neck joint are affected by rupture or over-stretching of the alar ligaments and/or capsule structures mostly caused by whiplash or similar biomechanical movements.

Symptoms during damaged alar ligaments besides vertigo often are

- dizziness

- reduced vigilance, such as somnolence

- seeing problems, such as seeing "stars," tunnel views or double contures

- Some patients tell about unreal feelings that stands in correlation with:

- depersonalization and attentual alterations

Medical doctors (MDs) generally do not endorse this explanation of vertigo due to a lack of any data to support it, from an anatomical or physiological standpoint. Often the patients who have an odyssey of medical consultations without any clear diagnosis and are sent to a psychiatrist because doctors think about depression or hypochondria. Standard imaging technologies such as CT Scan or MRI are not capable of finding instabilities without taking functional poses.

Neurochemistry of vertigo

The neurochemistry of vertigo includes six primary neurotransmitters that have been identified between the three-neuron arc that drives the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR). Many others play more minor roles.

Three neurotransmitters that work peripherally and centrally include glutamate, acetylcholine, and GABA.

Glutamate maintains the resting discharge of the central vestibular neurons and may modulate synaptic transmission in all three neurons of the VOR arc. Acetylcholine appears to function as an excitatory neurotransmitter in both the peripheral and central synapses. GABA is thought to be inhibitory for the commissures of the medial vestibular nucleus, the connections between the cerebellar Purkinje cells and the lateral vestibular nucleus, and the vertical VOR.

Three other neurotransmitters work centrally. Dopamine may accelerate vestibular compensation. Norepinephrine modulates the intensity of central reactions to vestibular stimulation and facilitates compensation. Histamine is present only centrally, but its role is unclear. It is known that centrally acting antihistamines modulate the symptoms of motion sickness.

The neurochemistry of emesis overlaps with the neurochemistry of motion sickness and vertigo. Acetylcholinc, histamine, and dopamine are excitatory neurotransmitters, working centrally on the control of emesis. GABA inhibits central emesis reflexes. Serotonin is involved in central and peripheral control of emesis but has little influence on vertigo and motion sickness.

Symptoms and diagnostic testing

True vertigo, as opposed to generally symptoms of lightheadedness or fainting, requires a symptom of disorientation or motion and may also have symptoms of nausea or vomiting, sweating, and abnormal eye movements (Bellot and Mikhail 2005). There may also be ringing in the ears, visual disturbances, weakness, decreased level of consciousness, and difficulty walking and/or speaking (Bellot and Mikhail 2005). Symptoms may last minutes or hours, and be constant or episodic (Bellow and Mikhail 2005).

Tests of vestibular system (balance) function include electronystagmography (ENG), rotation tests, Caloric reflex test (BCM 2006), and Computerized Dynamic Posturography (CDP).

Tests of auditory system (hearing) function include pure-tone audiometry, speech audiometry, acoustic-reflex, electrocochleography (ECoG), otoacoustic emissions (OAE), and auditory brainstem response test (ABR; also known as BER, BSER, or BAER).

Other diagnostic tests include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computerized axial tomography (CAT, or CT).

Treatment

Treatment is specific for underlying disorder of vertigo. Among treatments are medicine (taken orally, through the skin, or through an an IV), antibiotics (cause of bacterial infection of the middle ear), surgery (such as hole in the inner ear), dietary change (such as low salt diet for Meniere disease), or physical rehabilitation (Bellot and Mikhail 2005). Medications may include meclizine hydrocholoride (Antivert), scopolamine transdermal patch, promethazine hydrochloride (Phenergan), diazepam (Valium), and diphehydramine (Benadryl) (Bellot and Mikhail 2005). Vetibular rehabilitation may involve sitting on the edge of a table and laying down to one side until the vertigo ceases, then sitting up and lying down on the other side until it goes away, and repeating this until the condition resolves (Bellot and Mikhail 2005).

Possible treatments depending on the cause include:

- Vestibular rehabilitation

- Anticholinergics

- Antihistamines

- Benzodiazepines

- calcium channel antagonists, specifically Verapamil and Nimodipine

- GABA modulators, specifically gabapentin and baclofen

- Neurotransmitter reuptake inhibitors such as SSRI's, SNRI's and Tricyclics

- Antibiotics

- Surgery

- Dietary change

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baylor College of Medicine (BCM). Bobby R. Alford Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery. 2006. Core curriculum: Inner ear disease‚ÄďVertigo. Baylor College of Medicine. Retrieved January 7, 2008.

- Bello, A. J., and M. Mikhail. 2005. Vertigo eMedicineHealth. Retrieved January 7, 2008.

- Furman, J. M., S. P. Cass, and B. C. Briggs. 1998. Treatment of benign positional vertigo using heels-over-head rotation. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 107: 1046-1053.

- Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. 2007. Vertigo Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved January 7, 2008.

- Radtke, A., M. von Brevern, K. Tiel-Wilck, A. Mainz-Perchalla, H. Neuhauser, and T. Lempert. 2004. Self-treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: Semont maneuver vs Epley procedure. Neurology 63(1).

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.