Shabbatai Zevi

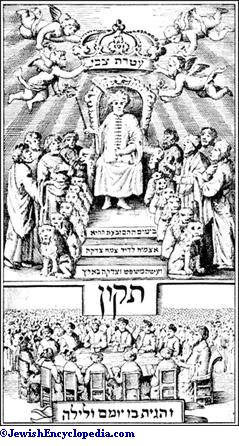

Sabbatai Zevi, (Hebrew: ◊©÷∑◊Ā◊Ď÷į÷ľ◊™÷∑◊ô ◊¶÷į◊Ď÷ī◊ô, Shabbetay Šļíevi) (other spellings include Shabbethai, Sabbetai,¬†; Zvi, Tzvi) (August 1, 1626 ‚Äď c. September 17, 1676) was a rabbi and Kabbalist who claimed to be the long-awaited Jewish Messiah and gained a major following among world Jewry in the mid-late seventeenth century. He was the founder of the Jewish Sabbatean movement and inspired the founding of a number of other similar sects, such as the Donmeh in Turkey.

Born in Smyrna in today's Turkey he became interested in Kabbalistic studies at an early age and soon developed a strong mystical and ascetic orientation. Already harboring messianic pretensions at the age of 22, he gathered followers and received several confirmations of his identity, but soon ran afoul of local rabbinical authorities. He later gained important disciples during his stays in Cairo and Jerusalem.

In the early 1660s, Sabbatai developed a significant following, and his fame spread to Jews everywhere. In Jerusalem, he again faced persecution from conservative Jewish authorities and returned to Smyrna, where he was welcomed with great fanfare, publicly proclaiming himself as Messiah in 1665. Jews throughout the world prepared to join him in a restored Kingdom of Israel the following year. However he soon found himself in prison in Istanbul. This only inflamed the expectation of Jews, however, who heard reports of Sabbatai's relatively good treatment and saw this as a precursor to the Ottoman sultan's submission to Sabbatai and the restoration of Israel.

A crisis arose, however, as Sabbatai was denounced to Ottoman authorities and, under severe threats, declared his own conversion to Islam. A great disillusionment ensued, but a wave of hope soon followed as Sabbatai, now given a privileged position in the sultan's court, showed indications that his supposed conversion might only be a subterfuge to win the Muslims to his cause. This double game, however, could not last, and Sabbatai was exiled to a small town in Montenegro, where he died alone in 1676.

His death did not entirely end his movement. A Jewish-Islamic sect known as Donmeh persists to this day, based on his teachings during his time in Turkey. European Sabbateanism became marginalized from the Jewish mainstream and caused a major controversy in the early eighteenth century under the leadership of Jacob Frank, who taught the abrogation of fundamental Jewish laws and ultimately led many of his followers to accept Christian baptism. A small contemporary movement of European and American Sabbateans operates today under the name of Donmeh West.

Early years

Sabbatai's family came from Patras, presently in Greece, and descended from the Greek-speaking Jews of the Ottoman Empire. They were neither Sephardi nor Ashkenazi, but belonged to a distinctive group known as Romaniotes. His father, Mordecai, was a poor poultry dealer. Later, when Smyrna became the center of Levantine trade with Europe, Mordecai became the Smyrnian agent of an English noble house, and he acquired considerable wealth.

In accordance with the Jewish custom, Sabbatai's father had him study the Talmud. He thus attended a yeshiva under the erudite rabbi of Smyrna, Joseph Escapa. On the other hand, he was fascinated by mysticism and the Kabbalah, in the prevailing style of Rabbi Isaac Luria. He found the "practical Kabbalah," with its asceticism&ndashthrough which its devotees claimed to be able to communicate with God and the angels, to predict the future, and to perform all sorts of miracles‚ÄĒespecially appealing.

Sabbatai was also much inclined to solitude. Like others of the time he married early, but he reportedly avoided intercourse with his wife. She therefore applied for a divorce, which he willingly granted. The same thing happened with a second wife. Later, he imposed the severe mortifications on his body: he meditated and prayed for long hours, bathed frequently in the sea in winter, and fasted for days on end. He reportedly lived constantly in either a state of complete ecstasy, or intense melancholy.

Messianic Career

A young man possessed of a beautiful singing voice, charismatic personality, and reputation as a devoted Kabbalistic ascetic, at age 22 Sabbatai revealed himself to a group at Smyrna as Messiah designated by God to restore the Kingdom of Israel. He dared even to pronounce the sacred name of God. This was of great significance to those acquainted with rabbinical and especially Kabbalistic literature. However, Sabbatai's authority at such a young age did not reach far enough for him to gain many adherents.

Among the first of those to whom he revealed his messiahship were Isaac Silveyra and Moses Pinheiro, the latter a brother-in-law of the Italian rabbi and Kabbalist Joseph Ergas. Sabbatai remained at Smyrna for several years, leading the pious life of a mystic, and giving rise to much argument in the community. The local college of rabbis watched Sabbatai closely. When his messianic pretensions became too bold, they put him and his followers under a ban of cherem, a type of excommunication in classical Judaism.

As a result, Sabbatai and his disciples were banished from Smyrna sometime in the early 1650s. Later, in Constantinople, he met the prophetic preacher Abraham ha-Yakini, who confirmed Sabbatai's messiahship. Ha-Yakini reportedly wrote an apocalyptic narrative entitled the The Great Wisdom of Solomon, which declared:

I, Abraham, was confined in a cave for 40 years, and I wondered greatly that the time of miracles did not arrive. Then was heard a voice proclaiming, "A son will be born in the Hebrew year 5386 (English calendar year 1626) to Mordecai Zevi; and he will be called Sabbetai. He will humble the great dragon; ... he, the true Messiah, will sit upon My throne."

Salonica, Cairo, and Jerusalem

With this document, Sabbatai traveled to the Kabbalistic center of Salonica. There he gained many adherents. Among the signs of his authority, he celebrated his mystical marriage as the ‚ÄúSon of God‚ÄĚ to the Torah. The rabbis of Salonica promptly banished him from the city.

After various wanderings, he settled in Cairo, Egypt, where he resided for about two years probably from 1660 to 1662. In Cairo, he met a wealthy and influential Jew named Raphael Joseph Halabi, who was also an official of Ottoman government. This gentleman became his financial supporter and one of the most zealous promulgators of his Sabbatai's messianic plans.

With the apocalyptic year 1666 approaching, Sabbatai traveled to Jerusalem. Arriving there in about 1663, he at first remained inactive, so as not to offend the community. He demonstrated his piety by frequent fasting, gaining the respect of many. Having a very melodious voice, he also used to sing psalms the whole night long. At other times he reportedly prayed at the graves of pious men and women, shedding floods of tears. He acted generously to the poor and became known for his distributing sweetmeats to the children on the streets.

Soon, when the Jewish community of Jerusalem faced severe pressure from corrupt Turkish officials, Sabbatai was chosen as the envoy to travel to Cairo to seek the monetary aid of Raphael Joseph Halabi, which was quickly forthcoming. This act brought the tremendous gratitude of the Jews of Jerusalem and gained great prestige for Sabbatai as a literal deliver of his people, if not yet on a messianic scale.

Marriage to Sarah

During a second stay at Cairo, Sabbetai also fulfilled his destiny to consummate a marriage with a physical bride, and no ordinary bride at that. Sarah was a Jewish orphan girl who had survived the Chmielnicki massacres in Poland, which wiped out a large portion of the Jewish population there. After ten years confined in a convent, she escaped, finding her way through Amsterdam to Livorno where she reportedly had to support herself through a life of prostitution. During this time she also came to believe that she was destined to become the bride of the Messiah, who was soon to appear.

The story of this girl and her destiny reached Cairo, and Sabbatai at once reported that such a wife had been promised to him in a dream. Messengers were sent to Livorno, and Sarah, now 16, was brought to Cairo, where she was married to Sabbatai at Halabi's house. Through her, a powerfully romantic element entered Sabbatai's career. Her beauty and eccentricity gained for him many new followers, and even her past lewd life was looked upon as an additional confirmation of his messiahship, since the prophet Hosea had been commanded by God to take a "wife of whoredom" as the first symbolic act of his own calling to restore the wayward ways of God's people.

Nathan of Gaza

Having Halabi's money, a charming wife, and many additional followers, Sabbatai triumphantly returned to Palestine. Passing through the city of Gaza, he met another man who was to become crucial in his subsequent messianic career. This was Nathan Benjamin Levi, known to history as Nathan of Gaza. He became Sabbatai's chief disciple, and professed to be the returned Elijah, the precursor of the Messiah. In 1665, Nathan announced that the messianic age was to begin in the following year. Sabbatai himself spread this announcement widely. Nathan, as Elijah, would conquer the world without bloodshed, and Sabbetai, the Messiah, would then lead the Ten Lost Tribes, together with the Jews of the diaspora, back to the Holy Land. These claims were widely circulated and believed by many Jews throughout Europe, Asia Minor, the Middle East, and Northern Africa.

Return to Smyrna

The rabbis of Jerusalem, however, regarded the movement with great suspicion, and threatened its followers with excommunication. Sabbatai then left for his native city of Smyrna, while his prophet, Nathan, proclaimed that henceforth Gaza, and not Jerusalem, would be the sacred city. On his way from Jerusalem to Smyrna, Sabbatai was enthusiastically greeted at Aleppo.

At Smyrna, which he reached in the autumn of 1665, even greater homage was paid to him. There, in the city's synagogue on the Jewish New Year, he publicly declared himself to be the Messiah, with the blowing of trumpets, and the multitude greeting him with: "Long live our King, our Messiah!"

The joy of his followers knew no bounds. Sabbatai, assisted by his wife, now became the leading member of the Jewish community. In this capacity he deposed the previous chief rabbi of Smyrna, Aaron Lapapa, and appointed in his place Hayyim Benveniste. His popularity grew with incredible rapidity, as not only Jews but Christians, too, also spread his story far and wide.

His fame extended to all countries. Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands all had centers where the messianic movement was ardently promulgated, and the Jews of Hamburg and Amsterdam received confirmation of the extraordinary events in Smyrna from trustworthy Christian travelers. A distinguished German scholar, Heinrich Oldenburg, wrote to Baruch Spinoza: "All the world here is talking of a rumor of the return of the Israelites... to their own country... Should the news be confirmed, it may bring about a revolution in all things" (Spinozae Epistolae No 33).

Sabbatai numbered many prominent rabbis as followers, including Isaac Aboab da Fonseca, Moses Raphael de Aguilar, Moses Galante, Moses Zacuto, and the above-mentioned Hayyim Benveniste. Even the secularized scholar Dionysius Mussafia Musaphia became one of Sabbatai's zealous adherents. Meanwhile, the Jewish community of Avignon, France, prepared to emigrate to the new messianic kingdom in the spring of 1666.

The adherents of Sabbatai apparently planned to abolish a number of the Jewish ritualistic observances because‚ÄĒaccording to an opinion in the Talmud‚ÄĒthey were to lose their obligatory character in the messianic age. The first step was the changing of the fast of the Tenth of Tevet to a day of feasting and rejoicing. Samuel Primo, who acted as Sabbatai's secretary, directed the following circular to the whole of Israel:

The first-begotten Son of God, Shabbetai Zevi, Messiah and Redeemer of the people of Israel, to all the sons of Israel, Peace! Since ye have been deemed worthy to behold the great day and the fulfillment of God's word by the Prophets, your lament and sorrow must be changed into joy, and your fasting into merriment; for ye shall weep no more. Rejoice with song and melody, and change the day formerly spent in sadness and sorrow into a day of jubilee, because I have appeared.

This message produced considerable excitement in Jewish communities, as many of the leaders who had hitherto regarded the movement sympathetically were shocked at these radical innovations. The prominent Smyrnian Talmudist Solomon Algazi and other members of the rabbinate who opposed the abolition of the fast, narrowly escaped with their lives.

Several additional traditional fast days were later turned to feast days in Sabbataian circles as well.

In Istanbul

At the beginning of the year 1666, Sabbatai left Smyrna for Istanbul, the Ottoman Empire's capital. The reason for his trip is unclear: either it was because he was compelled to do so by the city's Gentile authorities, or because of a hope that a miracle would happen in the Turkish capital to fulfill the prophecy of Nathan of Gaza that Sabbatai would place the Sultan's crown on his own head. As soon as he reached the landing-place, however, he was arrested at the command of the grand vizier and cast into prison in chains.

Sabbatai's imprisonment had no discouraging effect either on him or on his followers. On the contrary, the lenient treatment which he secured by means of bribes served to strengthen them in their messianic beliefs. In the meantime, all sorts of fabulous reports concerning the miraculous deeds which Shabbetai was performing in the Turkish capital were spread by Nathan and Primo among the Jews of Smyrna and in many other communities. The expectations of large numbers of Jews were raised to a still higher pitch.

At Abydos

| ‚Äú | Blessed be God who hath restored again that which was forbidden. | ‚ÄĚ |

After two months' imprisonment in Istanbul, Sabbatai was brought to the state prison in the castle of Abydos. Here he was treated very generously there, some of his friends even being allowed to accompany him. At Passover, he slew a paschal lamb for himself and his followers and ate it with its fat, a violation of the priestly law. He reportedly pronounced over it the benediction: "Blessed be God who hath restored again that which was forbidden."

The immense sums sent to him by his wealthier adherents, the charms of the queenly Sarah, and the reverential admiration shown him even by the Turkish officials enabled Sabbatai to display royal splendor in the castle prison of Abydos, accounts of which were exaggerated and spread among Jews in Europe, Asia, and Africa.

In some parts of Europe Jews began to make physical and financial preparation for a new "exodus." In almost every synagogue, Sabbatai's initials were posted, and prayers for him were inserted in the following form: "Bless our Lord and King, the holy and righteous Sabbatai Zevi, the Messiah of the God of Jacob." In Hamburg the council introduced this custom of praying for Sabbatai not only on Saturday, but also on Monday and Thursday. Sabbatai's picture was printed together with that of King David in many prayer-books, as well as his kabbalistic formulas and penances.

These and similar innovations caused great dissension in various communities. In Moravia, the excitement reached such a pitch that the government had to interfere, while in Morocco, the emir ordered a persecution of the Jews.

Sabbatai adopts Islam

After a meeting with the Polish Kabbalist and self-proclaimed prophet Nehemiah ha-Kohen turned sour, Nehemiah escaped in fear of his life to Istanbul, where he reportedly pretended to embrace Islam and betrayed the allegedly treasonable intent of Sabbatai to authorities. Sultan Mehmed IV commanded that Sabbatai be taken from Abydos to Adrianople, where the sultan's physician, a former Jew, advised him to convert to Islam or face dire consequences. Realizing the danger, and perhaps seeing an opportunity, Sabbatai took the physician's advice. On the following day, September 16, 1666, after being brought before the sultan, he cast off his Jewish garb and put a Turkish turban on his head; and thus his supposed conversion to Islam was accomplished.

| ‚Äú | God has made me an Ishmaelite; He commanded, and it was done. | ‚ÄĚ |

The sultan was much pleased and rewarded Sabbatai by conferring on him the title Effendi and appointing him as his doorkeeper with a high salary. Sarah and a number of Sabbatai's followers also went over to Islam. To complete his acceptance of Islam, Sabbatai was ordered to take an additional wife. Some days after his conversion he wrote to Smyrna: "God has made me an Ishmaelite; He commanded, and it was done." It is widely believed that Sabbatai had some connection with the Bektashi Sufi order during this time.

Disillusion

Sabbatai's conversion was devastating for his many and widespread followers. In addition to the misery and disappointment from within, Muslims and Christians jeered at and scorned the credulous Jews. The sultan even planned to decree that all Jewish children should be brought up in Islam, also that 50 prominent rabbis should be executed. Only the contrary advice of some of his counselors and of the sultan's mother prevented these calamities.

In spite of Sabbatai's apostasy, however, many of his adherents still tenaciously clung to him, claiming that his conversion was a part of the messianic scheme of tikkun, the Kabbalistic formula of cosmic restoration. This belief was upheld and strengthened by the prophet Nathan and Sabbatai's secretary Primo. In many communities, Sabbatai's feast-days, replacing traditional days of fasting, continued to be observed in spite of bans and excommunications.

Meanwhile, Sabbatai himself encouraged continued faith in his role. In March 1668, he announced that he had again been filled with the Holy Spirit at Passover, and had received a revelation. He reportedly published a mystical work addressed to the Jews in which it was claimed that he was indeed the true Messiah, in spite of his conversion, his object being to bring over thousands of Muslims to Judaism.

To the sultan, however, he said that his activity among the Jews was to bring them over to Islam. He therefore received permission to associate with his former co-religionists, and even to preach in their synagogues. He indeed seems to have succeeded in bringing over a number of Muslims to his Kabbalistic views, and, on the other hand, in converting many Jews to a type of Islam, thus forming a Judeo‚ÄďTurkish sect whose followers implicitly believed in him.

Gradually, however, the Turks tired of Sabbatai's double game. He was deprived of his salary and banished from Adrianople to Istanbul. In a village near the latter city he was one day discovered singing psalms in a tent with Jews, whereupon the grand vizier ordered his banishment to Dulcigno (today called Ulcinj), a small place in Montenegro, where he died in solitude in 1676.

Legacy

Sabbatai's Zevi's apostasy had two main effects in Judaism. First, those who maintained their faith in Sabbatai's beliefs became more and more mystical in their orientation sometimes adopting attitudes of extremism. In Poland, these marginalized Jews formed numerous secret societies known as "Sabbathai Zeviists," or "Shebs" (according to the Western pronunciation of "Sabbatai"). The members of these societies threw off the burden of strict Jewish dogma and discarded many religious laws and customs. From among this group rose the leader Jacob Frank, who influenced his followers to adopt a radical antinomianism [1] and eventually led many of them to accept baptism as Christians, in imitation of Sabbetai's own conversion to Islam.

Second, all these events strengthen the hand of the conservative Talmudists who had opposed Sabbatai, consequently weakening the position of Kabbalists in general, and the Lurianic Kabbalah specifically. Mainstream Judaism cast Kabbalistic study not only as superstition, but as morally and politically dangerous. Sabbatai having led the Jews into calamity by becoming enthralled with mysticism at an early age, Kabbalah study was banned to young men and forbidden to women altogether. Furthermore, the messianic hope itself came to be seen as something not to be spoken of in immediate terms.

Meanwhile, in Turkey, Sabbatai's teachings had formed a half-Jewish, half-Islamic sect that persisted through the centuries despite having to operate in secret. Although little is known about them, various groups called Donmeh (Turkish for "apostate") continue to follow Sabbatai Zevi today. Estimates of the numbers vary, but they seem to number close to 100,000 and perhaps many more. Isik University (a private university in Istanbul) and the Feyziye Schools Foundation under whose umbrella the University is operating, were rumored to be founded by the Karakash group of Donmeh.

A group calling itself Donmeh West, founded in California in 1983 by Reb Yakov Leib, considers itself a "Neo-Sabbatian collective," and draws on Sabbatai Zevi's teachings to form a syncretistic movement [2] which also draws heavily on Sufism, Judaism, and other faiths. Donmeh West does have direct historical ties to the Donmeh active in Turkey.

See also

- Messiah

- Islam and Judaism

- Sabbateans

- Jacob Frank

- Bar Kochba

- Donmeh

- Nathan of Gaza

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Asch, Sholem. Sabbatai Zevi: A Tragedy in Three Acts. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society: 1930. OCLC 193734

- Carlebach, Elisheva. Pursuit of Heresy: Rabbi Moses Hagiz and the Sabbatian Controversy. New York: Columbia University Press, 1990. ISBN 9780231071901

- Halperin, David J. Sabbatai Zevi: Testimonies to a Fallen Messiah. Oxford, Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2007. ISBN 9781904113256

- Freely, John. Lost Messiah: In Search of Sabbatai Sevi. London: Penguin, 2002. ISBN 0140284915

- Scholem, Gershom. Sabbatai Sevi: The Mystical Messiah: 1626-1676. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1973: ISBN 0691099162

- This article incorporates text from the 1901‚Äď1906 Jewish Encyclopedia, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved January 26, 2023.

- Shabbetai Zvi in Jewish Virtual Library ‚Äď www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.