Menander I

Menander I Soter, (The Saviour), known as Milinda in Indian sources, was one of the Indo-Greek rulers in northern India from c. 155 B.C.E. to 130 B.C.E. His territories covered the eastern dominions of the divided Greek empire of Bactria and extended to the modern Indian States of Punjab and Himachal Pradesh and the Jammu region. His capital was Sagala, a prosperous city in northern Punjab believed to be (modern Sialkot), a few kilometers west of what is now the border between India and Pakistan. He is one of the few Bactrian kings mentioned by Greek authors, among them Apollodorus of Artemita, who claims that the Greeks from Bactria were even greater conquerors than Alexander the Great, and that Menander was one of the two Bactrian kings, with Demetrius, who extended their power farthest into India.

He is also the first historical Westerner documented to have converted to Buddhism, renowned for his open-minded dialogues with followers of other religions.

History

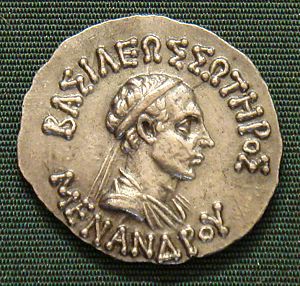

Obv: Greek legend, ╬ĺ╬Ĺ╬ú╬Ö╬Ť╬Ľ╬ę╬ú ╬ú╬ę╬Ą╬Ś╬í╬č╬ú ╬ť╬Ľ╬Ł╬Ĺ╬Ł╬ö╬í╬č╬ą (BASILEOS SOTEROS MENANDROU) lit. "Of Saviour King Menander".

Rev: Kharosthi legend: MAHARAJA TRATASA MENADRASA "Saviour King Menander." Athena advancing right, with thunderbolt and shield. Taxila mint mark.

The reign of Menander was long and successful. Generous findings of coins testify to the prosperity and extension of his empire and the finds of his coins are the most numerous and the most widespread of all the Indo-Greek kings. Precise dates of his reign, as well as his origin, remain elusive however. Guesses among historians have been that Menander was either a nephew (or a former general) of the Greco-Bactrian king Demetrius I, but the two kings are now thought to be separated by at least 30 years. Menander's predecessor in Punjab seems to have been the king Apollodotus I.

The Greek historian Strabo describes the powerful kingdom forged by Menander:

"The Greeks who caused Bactria to revolt grew so powerful on account of the fertility of the country that they became masters, not only of Ariana, but also of India, as Apollodorus of Artemita says: and more tribes were subdued by them than by AlexanderÔÇöby Menander in particular (at least if he actually crossed the Hypanis towards the east and advanced as far as the Ima├╝s), for some were subdued by him personally and others by Demetrius, the son of Euthydemus the king of the Bactrians; and they took possession, not only of Patalena, but also, on the rest of the coast, of what is called the kingdom of Saraostus and Sigerdis. In short, Apollodorus says that Bactriana is the ornament of Ariana as a whole; and, more than that, they extended their empire even as far as the Seres and the Phryni." (Strabo 11.11.1)[1]

Strabo also suggests that these Greek conquests went as far as the capital Pataliputra in northeastern India (today Patna):

- "Those who came after Alexander went to the Ganges and Pataliputra" (Strabo, 15.698).

The Indian records also describe Greek attacks on Mathura, Panchala, Saketa, and Pataliputra. This is particularly the case of some mentions of the invasion by Patanjali around 150 B.C.E., and of the Yuga Purana, which describes Indian historical events in the form of a prophecy:

"After having conquered Saketa, the country of the Panchala and the Mathuras, the Yavanas (Greeks), wicked and valiant, will reach Kusumadhvaja. The thick mud-fortifications at Pataliputra being reached, all the provinces will be in disorder, without doubt. Ultimately, a great battle will follow, with tree-like engines (siege engines)." (Gargi-Samhita, Yuga Purana chapter, No5).

In the West, Menander seems to have repelled the invasion of the dynasty of Greco-Bactrian usurper Eucratides, and pushed them back as far as the Paropamisadae, thereby consolidating the rule of the Indo-Greek kings in the northern part of the Indian Subcontinent.

The Milinda Panha gives some glimpses of his military methods:

- "Has it ever happened to you, O king, that rival kings rose up against you as enemies and opponents?

- -Yes, certainly.

- -Then you set to work, I suppose, to have moats dug, and ramparts thrown up, and watch towers erected, and strongholds built, and stores of food collected?

- -Not at all. All that had been prepared beforehand.

- -Or you had yourself trained in the management of war elephants, and in horsemanship, and in the use of the war chariot, and in archery and fencing?

- -Not at all. I had learnt all that before.

- -But why?

- -With the object of warding off future danger."

- (Milinda Panha, Book III, Chap 7)

Menander's empire survived him in a fragmented manner until the last Greek king Strato II disappeared around 10 C.E.

Menander was the first Indo-Greek ruler to introduce the representation of Athena Alkidemos ("Athena, saviour of the people") on his coins, probably in reference to a similar statue of Athena Alkidemos in Pella, capital of Macedon. This type was subsequently used by most of the later Indo-Greek kings.

Menander and Buddhism

The Milinda Pa├▒ha

According to tradition, Menander embraced the Buddhist faith, as described in the Milinda Pa├▒ha, a classical Pali Buddhist text on the discussions between Milinda and the Buddhist sage N─ügasena. He is described as constantly accompanied by a guard of 500 Greek ("Yonaka") soldiers, and two of his counsellors are named Demetrius and Antiochus. This type of discussion was known to ancient Greeks as a "sozo" (a conversation about salvation).

Obv: Greek legend, ╬ĺ╬Ĺ╬ú╬Ö╬Ť╬Ľ╬ę╬ú ╬ú╬ę╬Ą╬Ś╬í╬č╬ú ╬ť╬Ľ╬Ł╬Ĺ╬Ł╬ö╬í╬č╬ą (BASILEOS SOTEROS MENANDROU) lit. "Of Saviour King Menander" with eight-spoked wheel.

Rev: Kharosthi legend MAHARAJA TRATASA MENADRASA "Saviour King Menander," with palm of victory.

In the Milindanpanha, Menander is introduced as:

"King of the city of S├ógala in India, Milinda by name, learned, eloquent, wise, and able; and a faithful observer, and that at the right time, of all the various acts of devotion and ceremony enjoined by his own sacred hymns concerning things past, present, and to come. Many were the arts and sciences he knewÔÇöholy tradition and secular law; the S├ónkhya, Yoga, Ny├óya, and Vaisheshika systems of philosophy; arithmetic; music; medicine; the four Vedas, the Pur├ónas, and the Itih├ósas; astronomy, magic, causation, and magic spells; the art of war; poetry; conveyancing in a word, the whole nineteen. As a disputant he was hard to equal, harder still to overcome; the acknowledged superior of all the founders of the various schools of thought. And as in wisdom so in strength of body, swiftness, and valour there was found none equal to Milinda in all India. He was rich too, mighty in wealth and prosperity, and the number of his armed hosts knew no end." (Milinda Panha),[2]

Buddhist tradition relates that, following his discussions with N─ügasena, Menander adopted the Buddhist faith:

- "May the venerable Nâgasena accept me as a supporter of the faith, as a true convert from to-day onwards as long as life shall last!" (The Questions of King Milinda, Translation by T. W. Rhys Davids, 1890).

He then handed over his kingdom to his son and retired from the world:

- "And afterwards, taking delight in the wisdom of the Elder, he handed over his kingdom to his son, and abandoning the household life for the houseless state, grew great in insight, and himself attained to Arahatship!" (The Questions of King Milinda, Translation by T. W. Rhys Davids, 1890)

There is, however, little besides this testament to indicate that Menander in fact abdicated his throne in favor of his son. Based on numismatic evidence (evidence from coins), Sir Tarn believes that he in fact died, leaving his wife Agathocleia to rule as a regent, until his son Strato could rule properly in his stead. Despite the success of his reign, it is clear that after his death, his "loosely hung" empire splintered into a variety of Indo-Greek successor kingdoms, of various size and stability.

Other Indian accounts

- A second century B.C.E. relief from a Buddhist stupa in Bharhut, in eastern Madhya Pradesh (today at the Indian Museum in Calcutta), represents a foreign soldier with the curly hair of a Greek and the royal headband with flowing ends of a Greek king, and may be a depiction of Menander. In his left hand, he hold a branch of ivy, symbol of Dionysos. Parts of his dress, with rows of geometrical folds, are characteristically Hellenistic in style. On his sword appears the Buddhist symbol of the three jewels, or Triratana.

- A Buddhist reliquary found in Bajaur bears a dedicatory inscription referring to "the 14th day of the month of K─ürttika" of a certain year in the reign of "Mah─ür─üja Minadra" ("Great King Menander"):

- According to an ancient Sri Lankan source, the Mahavamsa, Greek monks seem to have been active proselytizers of Buddhism during the time of Menander: the Yona (Greek) Mahadhammarakkhita (Sanskrit: Mahadharmaraksita) is said to have come from "Alasandra" (thought to be Alexandria of the Caucasus, the city founded by Alexander the Great, near todayÔÇÖs Kabul) with 30,000 monks for the foundation ceremony of the Maha Thupa ("Great stupa") at Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka, during the second century B.C.E.:

- "From Alasanda the city of the Yonas came the thera ("elder") Yona Mahadhammarakkhita with thirty thousand bhikkhus." (Mahavamsa, XXIX)[4]

These elements tend to indicate the importance of Buddhism within Greek communities in northwestern India, and the prominent role Greek Buddhist monks played in them, probably under the sponsorship of Menander.

Coins of Menander

Menander has left behind an immense corpus of silver and bronze coins, more so than any other Indo-Greek king. During his reign, the fusion between Indian and Greek coin standards reached its apogee. The coins feature the legend (Greek: ╬ĺ╬Ĺ╬ú╬Ö╬Ť╬Ľ╬ę╬ú ╬ú╬ę╬Ą╬Ś╬í╬č╬ú ╬ť╬Ľ╬Ł╬Ĺ╬Ł╬ö╬í╬č╬ą (BASILEOS SOTEROS MENANDROU)/ Kharosthi: MAHARAJA TRATASA MENADRASA).

- According to Bopearachchi, his silver coinage begins with a rare series of drachms depicting on the obverse Athena and on the reverse her attribute the owl. The weight and monograms of this series match those of earlier king Antimachus II, indicating that Menander succeeded Antimachus II.

- On the next series, Menander introduces his own portrait, a hitherto unknown custom among Indian rulers. The reverse features his dynastical trademark: the so-called "Athena Alkidemos" throwing a thunderbolt, an emblem used by many of Menander's successors and also the emblem of the Antigonid kings of Macedonia.

- In a further development, Menander changed the legends from circular orientation to the arrangement seen on coin 4 to the right. This modification ensured that the coins could be read without being rotated, and was used without exception by all later Indo-Greek kings.

These alterations were possibly an adaption on Menander's part to the Indian coins of the Bactrian Eucratides I, who had conquered the westernmost parts of the Indo-Greek kingdom, and are interpreted by Bopearachchi as an indication that Menander recaptured these western territories after the death of Eucratides.

- Menander also struck very rare Attic standard coinage with monolingual inscriptions (coin 5), which were probably intended for use in Bactria (where they have been found), perhaps thought to demonstrate his victories against the Bactrian kings, as well as Menander's own claim to that the kingdom.

- The bronze coins of Menander featuring a manifold variation of Olympic, Indian and other symbols. It seems as though Menander introduced a new weight standard for bronzes.

Menander II, a separate Buddhist ruler

- Main article Menander the Just

Rev: Winged figure bearing diadem and palm, with halo, probably Nike. The Kharoshthi legend reads MAHARAJASA DHARMIKASA MENADRASA (Great King, Menander, follower of the Dharma, Menander).

A second king named Menander with the epithet Dikaios, "the Just" ruled in the Punjab after 100 B.C.E. Earlier scholars, such as A.Cunningham and W.W.Tarn, believed there were only one Menander and assumed that the king had changed his epithet and/or was expelled from his western dominions. A number of coincidences led them to this assumption:

- The portraits are relatively similar, and Menander II usually looks older than Menander I.

- The coins of Menander II feature several Buddhist symbols, which were interpreted as proof of the conversion mentioned in Milinda panha.

- The epithet Dikaios was translated into Kharosthi as Dharmikasa, which means "Follower of the Dharma" and was interpreted likewise.

However, modern numismatists as Bopearachchi and R.C. Senior have shown, by difference in coin findings, style and monograms, that there were indeed two distinct rulers. The second Menander could have been a descendant of the first, and his Buddhist symbols a means of alluding to his great ancestor's conversion.

Obv: Athena standing, with spear and palm branch, shield at her feet, making a benediction gesture with the right hand, similar to the Buddhist vitarka mudra. The Greek legend reads ╬ĺ╬Ĺ╬ú╬Ö╬Ť╬Ľ╬ę╬ú ╬ö╬Ö╬Ü╬Ĺ╬Ö╬č╬ą ╬ť╬Ľ╬Ł╬Ĺ╬Ł╬ö╬í╬č╬ą (Of King Menander the Just).

Rev: Buddhist lion. Kharoshti legend reads MAHARAJASA DHARMIKASA MENADRASA (Great King, follower of the Dharma, Menander).]]

With this distinction, the numismatical evidence for the Milinda panha is all but gone. The first Menander only struck a rare bronze series with a Buddhist wheel (coin 3).

Menander's death

Plutarch (Praec. reip. ger. 28, 6) reports that Menander died in camp while on campaign, thereby differing with the version of the Milindapanha. Plutarch gives Menander as an example of benevolent rule, contrasting him with disliked tyrants such as Dionysius, and goes on explaining that his subject towns disputed about the honour of his burial, ultimately sharing his ashes among them and placing them in "monuments" (possibly stupas), in a manner reminiscent of the funerals of the Buddha [5].

- "But when one Menander, who had reigned graciously over the Bactrians, died afterwards in the camp, the cities indeed by common consent celebrated his funerals; but coming to a contest about his relics, they were difficultly at last brought to this agreement, that his ashes being distributed, everyone should carry away an equal share, and they should all erect monuments to him." (Plutarch, "Political Precepts" Praec. reip. ger. 28, 6 [6]

Despite his many successes, Menander's last years may have been fraught with another civil war, this time against Zoilos I who reigned in Gandhara. This is indicated by the fact that Menander probably overstruck a coin of Zoilos.

The Milinda Panha might give some support the idea that Menander's position was precarious, since it describes him as being somewhat cornered by numerous enemies into a circumscribed territory:

- After their long discussion "Nagasaka asked himself "though king Milinda is pleased, he gives no signs of being pleased". Menander says in reply: "As a lion, the king of beasts, when put in a cage, though it were of gold, is still facing outside, even so do I live as master in the house but remain facing outside. But if I were to go forth from home into homelessness I would not live long, so many are my enemies" (Milinda Panha, Book III, Chapter 7, quoted in Boppearachchi).[7]

Theories of Menander's successors

Menander was the last Indo-Greek king mentioned by ancient historians, and the development after his death is, therefore, difficult to trace.

a) The traditional view, supported by W.W. Tarn and Boperachchi, is that Menander was succeeded by his Queen Agathokleia, who acted as regent to their infant son Strato I until he became an adult and took over the crown. Strato I used the same reverse as Menander I, Athena hurling a thunderbolt, and also the title Soter.

According to this scenario, Agathocleia and Straton I only managed to maintain themselves in the eastern parts of the kingdom, Punjab and at times Gandhara. Paropamisadae and Pushkalavati were taken over by Zoilos I, perhaps because some of Agathocleia's subjects may have been reluctant to accept an infant king with a queen regent.

b) Against this, R.C. Senior and other numismatics such as David Bivar have suggested that Straton I ruled several decades after Menander: they point out that Straton's and Agathocleia's monograms are usually different from Menander's, and overstrikes and hoard findings also associates them with later kings.

In this scenario, Menander was briefly succeeded by his son Thrason, of whom a single coin is known. After Thrason was murdered, competing kings such as Zoilos I or Lysias may have taken over Menander's kingdom. Menander's dynasty was thus dethroned and did not return to power until later, though his relative Nicias may have ruled a small principality in the Kabul valley.

Legacy and Significance

Buddhism

After the reign of Menander I, Strato I and several subsequent Indo-Greek rulers, such as Amyntas, Nicias, Peukolaos, Hermaeus, and Hippostratos, depicted themselves or their Greek deities forming with the right hand a symbolic gesture identical to the Buddhist vitarka mudra (thumb and index joined together, with other fingers extended), which in Buddhism signifies the transmission of the Buddha's teaching. At the same time, right after the death of Menander, several Indo-Greek rulers also started to adopt on their coins the Pali title of "Dharmikasa," meaning "follower of the Dharma" (the title of the great Indian Buddhist king Ashoka was Dharmaraja "King of the Dharma"). This usage was adopted by Strato I, Zoilos I, Heliokles II, Theophilos, Peukolaos and Archebios.

Altogether, the conversion of Menander to Buddhism suggested by the Milinda Panha seems to have triggered the use of Buddhist symbolism in one form or another on the coinage of close to half of the kings who succeeded him. Especially, all the kings after Menander who are recorded to have ruled in Gandhara (apart from the little known Demetrius III) display Buddhist symbolism in one form or another.

Both because of his conversion and because of his unequaled territorial expansion, Menander may have contributed to the expansion of Buddhism in Central Asia. Although the spread of Buddhism to Central Asia and Northern Asia is usually associated with the Kushans, a century or two later, there is a possibility that it may have been introduced in those areas from Gandhara "even earlier, during the time of Demetrius and Menander"[8].

Representation of the Buddha

The anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha is absent from Indo-Greek coinage, suggesting that the Indo-Greek kings may have respected the Indian an-iconic rule for depictions of the Buddha, limiting themselves to symbolic representation only. Consistently with this perspective, the actual depiction of the Buddha would be a later phenomenon, usually dated to the 1st century, emerging from the sponsorship of the syncretic Kushan Empire and executed by Greek, and, later, Indian and possibly Roman artists. Datation of Greco-Buddhist statues is generally uncertain, but they are at least firmly established from the first century.

Another possibility is that just as the Indo-Greeks routinely represented philosophers in statues (but certainly not on coins) in Antiquity, the Indo-Greek may have initiated anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha in statuary only, possibly as soon as the second-first century B.C.E., as advocated by Foucher and suggested by Chinese murals depicting Emperor Wu of Han worshipping Buddha statues brought from Central Asia in 120 B.C.E. An Indo-Chinese tradition also explains that Nagasena, also known as Menander's Buddhist teacher, created in 43 B.C.E. in the city of Pataliputra a statue of the Buddha, the Emerald Buddha, which was later brought to Thailand.

Stylistically, Indo-Greek coins generally display a very high level of Hellenistic artistic realism, which declined drastically around 50 B.C.E. with the invasions of the Indo-Scythians, Yuezhi and Indo-Parthians. The first known statues of the Buddha are also very realistic and Hellenistic in style and are more consistent with the pre-50 B.C.E. artistic level seen on coins.

This would tend to suggest that the first statues were created between 130 B.C.E. (death of Menander) and 50 B.C.E., precisely at the time when Buddhist symbolism appeared on Indo-Greek coinage. From that time, Menander and his successors may have been the key propagators of Buddhist ideas and representations: "the spread of Gandhari Buddhism may have been stimulated by Menander's royal patronage, as may have the development and spread of Gandharan sculpture, which seems to have accompanied it"[9]

Geography

In Classical Antiquity, from at least the first century, the "Menander Mons," or "Mountains of Menander," came to designate the mountain chain at the extreme east of the Indian subcontinent, today's Naga Hills and Arakan, as indicated in the Ptolemy world map of the first century geographer Ptolemy.

| Preceded by: Demetrius II of India |

Indo-Greek ruler (Paropamisadae, Arachosia, Gandhara, Punjab) 155/150-130 B.C.E. |

Succeeded by: (In Paropamisadae, Arachosia:) Zoilos I (In Gandhara, Punjab:) Agathokleia |

Notes

- ÔćĹ Strabo 11.11.1 Full text Perseus Project. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ÔćĹ Milinda Panha|The Questions of King Milinda, Translation by T. W. Rhys Davids, 1890 sacred-texts.com. Retrieved January 25, 2009.

- ÔćĹ Osmund Bopearachchi, (1991). Monnaies Gr├ęco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques, Catalogue Raisonn├ę. (Paris: Biblioth├Ęque Nationale de France, ISBN 2717718257), 19.

- ÔćĹ Chapter XXIX of the Mahavamsa: Text THE BEGINNING OF THE GREAT THUPA lakdiva.org. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ÔćĹ A passage in the "Mah─ü-parinibb├óna sutta" of the "Dighanikaya" relates the dispute of Indian kings over the ashes of the Buddha, which they finally shared between themselves and enshrined in a series of stupas.

- ÔćĹ Plutarch, "Political precepts," 147-148 online, Full text Library of Liberty Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ÔćĹ Osmund Bopearachchi. Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian and Indo-Parthian coins in the Smithsonian Institution. (Manohar, 1993. ISBN 0043940017), 33.

- ÔćĹ B.N. Puri. (2002). Buddhism in Central Asia. (New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 8120803728.)

- ÔćĹ Thomas Mc Evilly. (2002). The Shape of Ancient Thought. (Comparative studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies.) (New York: Allworth Press and the School of Visual Arts. ISBN 1581152035), 378

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boardman, John (1994). The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691036802

- Bopearachchi, Osmund. Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian and Indo-Parthian coins in the Smithsonian Institution. Manohar, 1993. ISBN 0043940017.

- Bopearachchi, Osmund (1991). Monnaies Gr├ęco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques, Catalogue Raisonn├ę. Paris: Biblioth├Ęque Nationale de France, ISBN 2717718257.

- Keown, Damien. Dictionary of Buddhism. Oxford University Press, ISBN 0198605609.

- McEvilley, Thomas (2002). The Shape of Ancient Thought. Comparative studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies. New York: Allworth Press and the School of Visual Arts. ISBN 1581152035

- No author (1992). The Crossroads of Asia. Transformation in Image and symbol. Ancient India and Iran Trust. ISBN 0951839918.

- Puri, B.N. (2002). Buddhism in Central Asia. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 8120803728.

External links

All links retrieved April 29, 2025.

- Coins of King Menander

- The Debate of King Milinda abridgement by Bhikkhu Pesala. buddhanet.net.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.