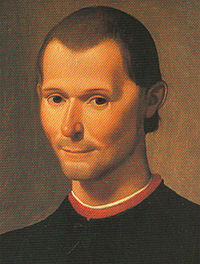

Niccolò di Bernado dei Machiavelli (May 3, 1469 â June 21, 1527) was an Italian political philosopher, musician, poet, and playwright. He was a key figure of the Renaissance, best known for his treatise on realist political theory, The Prince (Il principe) (1513). His other major work, Discourses on the First Ten Books of Livy, deserves to be better known for its exposition of the political theory and practice of democratic states.

Active in politics during a tumultuous era that saw popes leading armies, the wealthy city-states of Italy falling one after another into the hands of foreign powers, and governments rising and falling within a few weeks, Machiavelli analyzed the successes and failures he saw around him. The Prince described various means by which a prince could gain and retain control of his kingdom, evaluating each means in terms of how well it would strengthen the position of the prince while serving the public interest. Machiavelliâs focus on practical success at the expense of traditional moral values earned him the reputation of an amoralist. The term "Machiavellian," originally used by some of his contemporaries in discussions of "just" reasons of state, has come to describe one who deceives and manipulates others for gain, and judges the importance of actions by how well they achieve the desired result.

Life

Early life

Relatively little is known for certain about Machiavelli's early life. Machiavelli was born on May 3, 1469, in Florence, Italy, the second son of Bernardo di Niccolò Machiavelli and his wife Bartolommea di Stefano Nelli. Machiavelli's family had been prominent in Florence since the thirteenth century, sometimes holding important offices. His father, a lawyer, was among the poorest members of the family; he lived frugally, administering a small landed property near the city and supplementing his meager income with his law practice, which was restricted because he was debarred from any public office as an insolvent debtor of the commune of Florence. Machiavelli later wrote that he had âlearned to do without before he learned to enjoy.â

Poverty may have been the reason why he did not receive the same education as other talented Florentine youths, who studied Greek and Latin under Politian. Machiavelli never studied Greek; according to his father's memoirs, he studied Latin under obscure teachers and educated himself from the books in his home. This isolation probably contributed to the originality of his thought and the force of his style. After achieving a good grasp of the Latin and Italian classics, he entered government service as a clerk in 1494.

That same year, Florence expelled the Medici family, who had ruled the city for nearly sixty years, and restored the Republic of Florence. In 1498, after the changes in the Florentine government following the execution of Savonarola, an ascetic monk who tried to impose extreme political and religious reforms on the republic, and the triumph of the opposing faction, Machiavelli was named as a member of the council responsible for diplomatic negotiations and military matters. Machiavelli, 29 years old and completely unknown, was made head of the second chancery (cancelleria), which originally dealt with internal affairs of the republic, but was later merged with the secretariat of âthe Tenâ (i Dieci), the executive council. Machiavelli was also secretary to the magistracy, which directed foreign affairs and defense in the name of the Signoria, or governing council. The chancellors were entrusted with diplomatic missions to Italian and foreign courts when it was not desirable to send ambassadors.

Diplomatic missions

Machiavelli's first important mission was to the French court in 1500. From 1499 to 1512, Machiavelli was sent on a number of diplomatic missions to the court of Louis XII in France, Ferdinand II of Spain, and the pope in Rome. When he returned to Florence after six months in France in 1499, he found the republic on the verge of ruin as a result of the ambitions of Cesare Borgia, who was attempting to create a principality for himself in central Italy. Machiavelli was sent twice to Cesare Borgia, and witnessed Borgiaâs bloody vengeance on his mutinous captains at the town of Sinigaglia (December 31, 1502), of which he wrote a famous account, On the Manner Adopted by the Duke Valentino to Kill VitellozzoâŚ. (Descrizione del modo tenuto dal Duca Valentino nello ammazzare Vitellozzo⌠). The strong and sinister leader captured the imagination of Machiavelli, who adapted Borgiaâs methods to his own ideal of a ânew prince.â He did not admire Borgia as a person; after the death of Pope Alexander VI (father of Cesare Borgia) and his successor, Pope Pius III, Machiavelli was sent to Rome for the conclave that elected Pope Julius II, an enemy of the Borgias. He celebrated the imprisonment of Cesare, which, he said, âhe deserved as a rebel against Christ.â

In France, where he went on a second mission early in 1504, and in Romagna, Machiavelli developed the idea of giving the Florentine state a militia of its own, recruited from the peoples under its control. Immediately after his return from Rome, he persuaded the gonfalonier to have a law passed establishing a militia (1505). In 1506, as the importance of the new militia increased, Machiavelli was made secretary of the council of âthe Nineâ which controlled it. The territory of the republic was divided into districts, and Machiavelli himself carried out inspections and oversaw the levies.

In December 1507, Florence's gonfalonier sent Machiavelli on another journey to report on the Holy Roman emperor, Maximilian I, who was preparing an invasion of Italy from Germany. On the day after his return to Florence (June 17, 1508), Machiavelli produced a Report on the State of Germany (Rapporto delle cose della Magna), which together with the literary version published four years later, pointed out with keen insight the political strengths and weaknesses of the German nation, but were not complete and accurate sources of information.

In 1509, Machiavelli commanded the newly-formed Florentine militia in an effort to recapture the city of Pisa, and passionately insisted on accompanying his soldiers in the front lines. Pisa capitulated on June 8, 1509. In July 1510, Machiavelli was sent to France again to attempt to persuade Florence's ally, Louis XII, to make peace with Pope Julius IIâor at least to avoid involving Florence in a war that would bring the republic to ruinâemphasizing that a neutral Florence could be useful to the French. The mission, which resulted in the Ritratto di cose di Francia, was not successful, and he returned in October 1510 convinced that Florence would be involved in a major war between the French king and the pope. At the end of the summer of 1511, he went to France again to ask Louis XII to remove a schismatic council that he was sponsoring in Pisa and which had brought the anger of Julius II upon the Florentines. On his return from France, Machiavelli himself went to Pisa and removed this council, but the army of the pope's Holy League was on its way to punish Florence. The gonfalonier Soderini was deposed, and in 1512 the Medici family returned as masters of the city.

Under the Medici

Machiavelli lost his position and was forbidden to enter the governmental Palazzo della Signoria. Early in 1513, Machiavelli was accused of complicity in a plot against the Medicis. Imprisoned, he maintained his innocence even under severe torture. He was finally released from prison, but his freedom was restricted. In the meantime, Julius II had died, and Giovanni de' Medici had become Pope Leo X. Machiavelli composed a pious Canto degli spiriti beati (âSong of the Blessed Spiritsâ) for the occasion and tried in vain to get into the good graces of the Medici.

Reduced to poverty, Machiavelli sought refuge in the little property near Florence that he had inherited from his father. There he employed his leisure in writing, between spring and autumn 1513, his two most famous works, The Prince (Il principe) and a large part of the Discourses on the First Ten Books of Livy (Discorsi sopra la prima deca di Tito Livio). In a famous letter to his friend Francesco Guicciardini, historian and Florentine diplomat, Machiavelli described how he spent his days:

When evening comes, I return home [from work and from the local tavern] and go to my study. On the threshold I strip naked, taking off my muddy, sweaty workaday clothes, and put on the robes of court and palace, and in this graver dress I enter the courts of the ancients and am welcomed by them, and there I taste the food that alone is mine, and for which I was born. And there I make bold to speak to them and ask the motives of their actions, and they, in their humanity, reply to me. And for the space of four hours I forget the world, remember no vexation, fear poverty no more, tremble no more at death; I pass indeed into their world.[1]

During this time Machiavelli also wrote the comedy The Mandrake (Commedia di Callimaco e di Lucrezia, later La Mandragola) (1518), satirizing the wickedness and corruption of men, particularly of the clergy.

Machiavelli hoped in vain that The Prince, dedicated to Lorenzo de' Medici, ruler of Florence from 1513, would gain him an official position that would support his family and satisfy his desire for action. His prospects improved when, on the death of Duke Lorenzo, the Cardinal Giulio de' Medici came to govern Florence. He was presented to the Cardinal by Lorenzo Strozzi, to whom in gratitude he dedicated the dialogue Dell'arte della guerra (1520) which is complementary to his two political treatises.

The cardinal first sent Machiavelli to Lucca on a matter of small importance. Finally the cardinal agreed to have Machiavelli elected official historiographer of the republic, a post to which he was appointed by the University of Florence in November 1520 with a salary of 57 gold florins a year, later increased to 100. Under the terms of his contract, Machiavelli was permitted to undertake additional employment. In the meantime, he was to compose for the Medici Pope Leo X a Discorso on the organization of the government of Florence after the death of Duke Lorenzo; in this he boldly advised the Pope to restore the city's ancient liberties. Shortly after, in May 1521, he was sent to the Franciscan chapter at Carpi.

After the death of Pope Adrian VI in September 1523, Giulio de' Medici became Pope Clement VII. In June 1525, Machiavelli presented the pope with eight books of the Istorie fiorentine, his official history of Florence, and received 120 florins and encouragement to continue the work. In April 1526 Machiavelli was elected secretary of a five-man body responsible for superintending the fortifications of Florence. Next, Machiavelli went with the army to join Francesco Guicciardini, the pope's lieutenant, against the Holy Roman emperor Charles V, until the sack of Rome by the emperor's forces brought the war to an end in May 1527. Since Florence had cast off the Medici and regained its freedom, Machiavelli on his return hoped to be restored to his old post in the chancery, but his loyalty to his native Florence was ignored because of his cooperation with the Medici. Following this disappointment, Machiavelli fell ill and died within a month. His resting place is unknown; however, a cenotaph in his honor was placed at the Church of Santa Croce in Florence.

Thought and works

Machiavelli was born into a tumultuous era, one that saw popes leading armies and wealthy city-states of Italy falling one after another into the hands of France, Spain, and the Holy Roman Empire. It was a time of constantly shifting alliances, mercenaries who changed sides without warning, governments rising and falling in the space of a few weeks, and the rise of Lutheranism. Surrounded by these circumstances, Machiavelli turned his penetrating mind to analyzing the successes and failures he saw around him. The reports that he wrote on France, Germany, and Rome in his capacity as chancellor showed more occupation with political theory and concepts than with actual details. Wherever he went, Machiavelli observed the activity around him in terms of its ultimate outcome.

His two most famous works, The Prince and a large part of the Discourses on the First Ten Books of Livy were both written in 1513 during a period of unemployment.

The Prince

Machiavelli's best known work is The Prince (1513), a practical guide to the exercise of power over a Renaissance principality. It was written in hopes of securing the favor of the Medici family and was therefore deliberately provocative. Machiavelli argued that the character and ability of the leader determined the success of the state in the face of unpredictable fortune. He described various means by which a prince could gain and retain control of his kingdom, evaluating each in terms of how well it would strengthen the position of the prince while serving the public interest. He focused primarily on what he called the principe nuovo or "new prince," under the assumption that a hereditary prince needed only to carefully maintain the institutions that the people are used to; a new prince had the much more difficult task of stabilizing his new found power and building a structure that would endure.

Machiavelli sought a leader who could redeem Italy by overcoming political corruption, the weakness of the Italian states, and the threat of foreign conquest. These difficult circumstances did not allow for weakness or error. The practical techniques which Machiavelli recommended in The Prince were suited to the times and took the reality of human nature into account. Machiavelli remarked that if mankind had not been wicked, he would not have proposed certain cynical precepts. He longed for a society of good and pure men, seeking it in ancient times and in the less civilized nations, which he believed to be less corrupt.

The prince was to be publicly above reproach, but might be required to do evil things in private, in order to maintain his position and the stability of the state. Machiavelliâs focus on practical success at the expense of traditional moral values earned him the reputation of an amoralist who advocated ruthlessness, deception, and cruelty. Though Machiavelli himself had deep religious feelings, in The Prince he subordinated religion to the needs of the state and made it into a political tool. The Roman Catholic Church put the work in its Index Librorum Prohibitorum and it was viewed in a negative light by many humanists, including Erasmus.

A careless reading of The Prince could easily lead one to believe that its central argument is that "the ends justify the means"; that any evil action can be justified if it is done for a good purpose. Machiavelli, however, limited the circumstances under which an evil action could be justified. First, he specified that the only acceptable end was the stabilization and health of the state; individual power for its own sake was not an acceptable end and did not justify evil actions. Second, Machiavelli did not dispense entirely with morality nor advocate wholesale selfishness or degeneracy. Instead he clearly laid out criteria for the acceptability of a cruel action (it must be swift, effective and short-lived).

The term "Machiavellian" was used by some of Machiavelli's contemporaries in the introductions of political tracts of the sixteenth century that promoted "just" reasons of state, most notably those of Jean Bodin and Giovanni Botero. The pejorative term "Machiavellian" is used today to describe one who deceives and manipulates others for gain, and judges the importance of actions by how well they achieve the desired result.

VirtĂš and Fortuna

In The Prince, Machiavelli developed a complex relationship between ethics and politics that associated princely âvirtuâ with the capacity to understand and act within the political world as it âis,â and with the ability to dispense violence and practice deception when needed. Machiavelli viewed politics as a realm of appearances, where the practice of moral or Christian virtues often resulted in a princeâs downfall and knowing âhow not to be goodâ might achieve greater security and well-being for both prince and people. The Italian word virtĂš would normally translate into English as âvirtue,â connoting conventional moral goodness. Machiavelli employed the concept of virtĂš to refer to the range of personal qualities necessary for the prince to âmaintain his stateâ and to âachieve great things,â the two standards of political success.

Machiavelli warned that the princeâs possibilities for success were always mediated by Fortuna (fortune), the enemy of political order and the ultimate threat to the safety and security of the state. One aspect of virtĂš was the ability of a prince to adapt his procedures to the times and his nature to âthe necessity of the case.â In chapter 25 of The Prince, Machiavelli compared Fortuna to âone of our destructive rivers which, when it is angry, turns the plains into lakes, throws down the trees and buildings, takes earth from one spot, puts it in another; everyone flees before the flood; everyone yields to its fury and nowhere can repel it.â The furor of a raging river, however, did not mean that its depredations were beyond human control; it was possible to take precautions to divert the worst consequences of the natural elements. âThe same things happen about Fortuna,â Machiavelli observed. âShe shows her power where virtĂš and wisdom do not prepare to resist her, and directs her fury where she knows that no dikes or embankments are ready to hold herâ (Machiavelli 1965, 90). A prince could resist Fortuna by preparing, with âvirtĂš and wisdomâ for her inevitable arrival. He observed from his own experience that âit is better to be impetuous than cautiousâ in dealing with fortune, and that those who took aggressive action were usually more successful.

Criticism of Machiavelliâs thought

The ideas expressed by Machiavelli in The Prince have been the subject of controversy since the sixteenth century, when some denounced him as an apostle of the devil, and others who were sympathetic to his thought enunciated the doctrine of âreason of stateâ (Viroli 1992). The main object of debate was Machiavelli's attitude toward conventional moral and religious standards of human conduct, which some considered to be immoral. Leo Strauss (1957, 9-10) called Machiavelli a âteacher of evilâ on the grounds that he counseled leaders to avoid the common values of justice, mercy, temperance, wisdom, and love of their people, and to use cruelty, violence, fear, and deception. Benedetto Croce (1925) viewed Machiavelli as simply a ârealistâ or a âpragmatistâ advocating the suspension of commonplace ethics in matters of politics. Ernst Cassirer (1946) described Machiavelliâs attitude as scientific, distinguishing between the âfactsâ of political life and the âvaluesâ of moral judgment. Quentin Skinner (1978), concentrating on the claim in The Prince that a head of state ought to do good if he can, but must be prepared to commit evil if he must (Machiavelli 1965, 58), argued that Machiavelli preferred conformity to moral virtue and that the commission of vicious acts by a ruler is a âlast bestâ option.

Some readers have construed The Prince as a work of satire. Jean-Jacques Rousseau long ago remarked that the real lesson of The Prince is to expose, rather than celebrate, the immorality of one-man rule. Garrett Mattingly (1958) pronounced Machiavelli the supreme satirist, pointing out the foibles of princes and their advisers, and pointed out that Machiavelli later wrote biting popular stage comedies. Mary Deitz (1986) asserted that Machiavelli's advice was actually a trap designed to undo the ruler if the advice were taken seriously and followed.

The Prince speaks with equal disdain and admiration about the condition of the contemporary church and its pope (Machiavelli 1965, 29, 44â46, 65, 91â91). Many scholars have taken this to indicate that Machiavelli was himself profoundly anti-Christian, preferring the pagan civil religions of ancient societies, which he regarded as more suitable for a city endowed with virtĂš (Sullivan 1996). Others portray Machiavelli as a man of conventional piety, prepared to respect the external rites of worship but not deeply devoted to the tenets of Christian faith. Sebastian de Grazia (1989) argued that Machiavelli was not indifferent to Christianity, demonstrating that central biblical themes run throughout Machiavelli's writings, and that they exhibit a coherent conception of a divinely centered and ordered cosmos guided by a divine will and plan.

Discorsi

Discourse on the First Ten Books of Titus Livy or Discorsi (which comprise the early history of Rome) (1513) was a series of lessons on how a republic should be started, structured, and maintained. Each discourse began with a principle, supported with examples from Livy's history of Rome or other ancient models, and then gave a contemporary example from fifteenth- or sixteenth-century Italy. Many of the ideas set forth in Discorsi, including the concept of checks and balances, the strength of a tripartite structure, and the superiority of a republic over a principality, are as valid today as they were six centuries ago, and clear applications of his practical political philosophy can be found in the governments of many democracies today including the United States.

Other works

His History of Florence (Istorie fiorentine) shows the same power and originality as Machiavelliâs earlier works. It was written in several stages and was continued during Machiavelliâs later years. Affected by the necessity of avoiding offense to his powerful patrons, he wrote history more as a politician than a historian, often accepting sources uncritically and accommodating facts to his thesis. The Art of War (Dell'arte della guerra) (1520) explained in detail effective procedures for the acquisition, maintenance, and use of a military force.

Machiavelli also wrote plays (Clizia, Mandragola), poetry (Sonetti, Canzoni, Ottave, Canti carnascialeschi), novels (Belfagor arcidiavolo), and translated classical works.

Legacy

While The Prince, Machiavelli's better-known work, is of great historical interest and teaches valuable lessons about preparing for the future, his Discorsi have probably made a more constructive and long-lasting contribution to political science by taking important concepts of republican government from ancient Rome and developing them in a more modern context which influenced European thinkers. In some respects, Machiavelli can be regarded as the founder of âmodernâ pragmatic political science, in contrast to the classical Aristotelian political science of virtue.

Original works

- Discorso sopra le cose di Pisa, 1499

- Del modo di trattare i popoli della Valdichiana ribellati, 1502

- Del modo tenuto dal duca Valentino nell' ammazzare Vitellozzo Vitelli, Oliverotto da Fermo, etc., 1502 (Description of the Methods Adopted by the Duke Valentino when Murdering Vitellozzo Vitelli, Oliverotto da Fermo, the Signor Pagolo, and the Duke di Gravina Orsini)

- Discorso sopra la provisione del danaro, 1502

- Decennale primo (poem in terza rima), 1506

- Ritratti delle cose dell'Alemagna, 1508â1512

- Decennale secondo, 1509

- Ritratti delle cose di Francia, 1510

- Discorsi sopra la prima deca di Tito Livio, 3 vols., 1512â1517 (Discourses on Livy)

- Il principe, 1513 (The Prince)

- Andria, comedy translated from Terence, 1517

- Mandragola, (prose comedy in five acts, with prologue in verse) (The Mandrake), 1518

- Della lingua (dialog), 1514

- Clizia, comedy in prose, 1525

- Belfagor arcidiavolo (novel), 1515

- Asino d'oro (poem in terza rima, a new version of the The Golden Ass, a classic work by Apuleius), 1517 (The Golden Ass)

- Dell'arte della guerra, 1519â1520 (The Art of War)

- Discorso sopra il riformare lo stato di Firenze, 1520

- Sommario delle cose della citta di Lucca, 1520

- Vita di Castruccio Castracani da Lucca, 1520 (The Life of Castruccio Castracani of Lucca)

- Istorie fiorentine, eight books, 1520â1525 (Florentine Histories, commissioned by Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici who went on to become Pope Clement VII)

- Frammenti storici, 1525

See also

- Political Philosophy

- Republicanism

Notes

- â The Literary Works of Machiavelli, trans. Hale (Oxford, 1961), p. 139.

Bibliography

There are numerous books about Machiavelli. Select titles only.

Primary sources

- Machiavelli, Niccolo. 2003. The Art of War. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226500403, ISBN 9780226500409, ISBN 0226500462, ISBN 9780226500461

- Machiavelli, Niccolò; Julia Conaway Bondanella and Peter E. Bondanella. 1997. Discourses on Livy. Oxford World's Classics. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192829459

- Machiavelli, Niccolò, et al. 1940. The Prince and the Discourses. New York: Modern Library.

- Machiavelli, Niccolò; Carl von Clausewitz and Antoine Henri de Jomini. 2007. The Prince, On War and The Art of War, special edition of three all-time classics on politics and war by Niccolo Machiavelli (The Prince, as translated by W. K. Marriott), Carl von Clausewitz (On War, as translated by J. J. Graham) and Antoine Henri de Jomini (The Art of War, as translated by G. H. Mendell and W.P. Craighill). Rockville, MD: Arc Manor. ISBN 9780978653651, ISBN 0978653653, ISBN 0978653653, ISBN 9780978653651

Secondary sources

- Baron, Hans. 1997. "Machiavelli: The Republican Citizen and Author of 'The Prince.'" In Dunn and Harris, Machiavelli. Great Political Thinkers 5. Cheltenham, UK: E. Elgar. ISBN 1858981018

- Bock, Gisela; Quentin Skinner and Maurizio Viroli (eds.). 1990. Machiavelli and Republicanism. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521383765

- Donaldson, Peter S. 1988. Machiavelli and Mystery of State. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521345464

- Magee, Brian. 2001. The Story of Philosophy. New York: DK Publishing, Inc., pp. 72-73. ISBN 078943511X

- Najemy, John M. 1996. "Baron's Machiavelli and Renaissance Republicanism." American Historical Review 101(1): 119-129.

- Pocock, J. G. A. 1975. The Machiavellian Moment: Florentine Political Thought and the Atlantic Republican Tradition. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691075603

- Soll, Jacob. 2005. Publishing The Prince: History, Reading and the Birth of Political Criticism. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472114735

- Sullivan, Vickie B. (ed.). 2000. The Comedy and Tragedy of Machiavelli: Essays on the Literary Works. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300082584

- Sullivan, Vickie B. 1996. Machiavelli's Three Romes: Religion, Human Liberty, and Politics Reformed. Northern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0875802133

- Viroli, Maurizio. 2000. Niccolò's Smile: A Biography of Machiavelli. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. OCLC 46640125

- Whelan, Frederick G. 2004. Hume and Machiavelli: Political Realism and Liberal Thought. Lexington. ISBN 0739106317

External links

All links retrieved June 30, 2025.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entries:

- eMachiavelli.com â Machiavelli's works, their summaries, and bibliography

- Works by Machiavelli. Project Gutenberg â Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

- Machiavelli, Niccolo. "The Seven Books on the Art of War" â the Marxists Internet Archive, The Constitution Society

- Works by Niccolò Machiavelli at the IntraText Digital Library â Text, concordances and frequency list

General philosophy sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.