John Hood

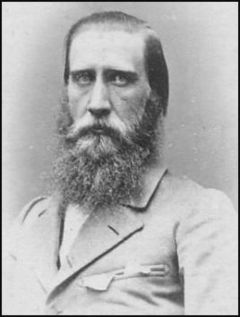

| John Bell Hood | |

|---|---|

| June 1 or June 29, 1831 – August 30, 1879 | |

Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood | |

| Nickname | "Sam," "Old Wooden Head" |

| Place of birth | Owingsville, Kentucky |

| Place of death | New Orleans, Louisiana |

| Allegiance | United States Army Confederate States Army |

| Years of service | 1853–61 (USA) 1861–65 (CSA) |

| Rank | Lieutenant General |

| Commands held | Texas Brigade Army of Tennessee |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War * Peninsula Campaign * Seven Days Battles * Second Battle of Bull Run * Battle of Antietam * Battle of Fredericksburg * Battle of Gettysburg * Battle of Chickamauga * Atlanta Campaign * Franklin-Nashville Campaign - Battle of Franklin II - Battle of Nashville |

John Bell Hood (June 1[1] or June 29,[2] 1831 – August 30, 1879) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War. Hood had a reputation for bravery and aggressiveness that sometimes bordered on recklessness. Arguably one of the best brigade and division commanders in the Confederate States Army, Hood became increasingly ineffective as he was promoted to lead larger, independent commands, and his career was marred by his decisive defeats leading an army in the Atlanta Campaign and the Franklin-Nashville Campaign. These reversals damaged his reputation but hastened the end of a conflict that divided families and a nation and saw the loss of 258,000 lives and many permanent injuries. Academics are still debating exactly what caused the war. However, had the Confederates won, slavery would have continued, at least for the foreseeable future, in the South, and the Union would have lost eleven out of its then 23 states and seven territories.

Early life

Hood was born in Owingsville, in Bath County, Kentucky, and was the son of John W. Hood, a doctor, and Theodosia French Hood. He was the cousin of future Confederate general G.W. Smith and the nephew of U.S. Representative Richard French. French obtained an appointment for Hood at the U.S. Military Academy, despite his father's reluctance to support a military career for his son. Hood graduated in 1853, ranked 44th in a class of 52, after a tenure marred by disciplinary problems and near-expulsion in his final year. At West Point and in later Army years, he was known to friends as "Sam." His classmates included James B. McPherson and John M. Schofield; he received instruction in artillery from George H. Thomas. These three men became Union Army generals who opposed Hood in battle.

Hood was commissioned a second lieutenant in the 4th U.S. Infantry, served in California, and later transferred to the 2nd U.S. Cavalry in Texas, where he was commanded by Colonel Robert E. Lee. While commanding a reconnaissance patrol from Fort Mason, Hood sustained one of the many wounds that marked his lifetime in military service—an arrow through his left hand in action against the Comanches at Devil's River, Texas.

Civil War

Brigade and division command

Hood resigned from the U.S. Army immediately after Fort Sumter and, dissatisfied with the neutrality of his native Kentucky, decided to serve his adopted state of Texas. He joined the Confederate army as a cavalry captain, but by September 30, 1861, was promoted to be colonel in command of the 4th Texas Infantry, which was stationed near the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia.[3]

Hood became the brigade commander of the unit that was henceforth known as Hood's Texas Brigade on February 20, 1862, part of the Confederate Army of the Potomac, and was promoted to brigadier general on March 3, 1862. Leading the Texas brigade as part of the Army of Northern Virginia in the Peninsula Campaign, he established his reputation as an aggressive commander, eager to lead his troops personally into battle from the front. His men called him "Old Wooden Head." At the Battle of Gaines' Mill on June 27, he distinguished himself by leading a brigade charge that broke the Union line, the most successful Confederate performance in the Seven Days Battles. While Hood escaped the battle with no injuries, every other officer in his brigade was killed or wounded.

Because of his success on the Peninsula, Hood was given command of a division in Maj. Gen. James Longstreet's First Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia. He led the division in the Northern Virginia Campaign and continued his reputation as the premier leader of shock troops during Longstreet's massive assault on John Pope's left flank at the Second Battle of Bull Run, which nearly destroyed the Union army. In the pursuit of Union forces, Hood was involved in a dispute over captured ambulances with a superior officer, Nathan Evans. Longstreet had Hood arrested over the dispute and ordered him to leave the army, but Robert E. Lee intervened and retained him in service. During the Maryland Campaign, just before the Battle of South Mountain, Hood was in the rear, still in virtual arrest. His Texas troopers shouted to General Lee as he rode by, "Give us Hood!" Lee restored Hood to command, despite Hood's refusal to apologize for his conduct. The issue was never fully resolved. During the Battle of Antietam, Hood's division came to the relief of Stonewall Jackson's corps on the Confederate left flank. Hood's men surprised the larger Union forces of General Joseph Hooker in the cornfield outside of Dunker Church and the area was quickly turned into a ghastly scene. Jackson was impressed with Hood's performance and recommended his promotion to major general, which occurred on October 10, 1862. He was assigned to command of the I Corps. By this time he had gained a reputation for skill and valor in the battlefield.

In the Battle of Fredericksburg in December, Hood's division saw little action. And in the spring of 1863, he missed the great victory of the Battle of Chancellorsville because most of Longstreet's Corps was on detached duty in Suffolk, Virginia.

Gettysburg

At the Battle of Gettysburg, Longstreet's Corps arrived late on the first day, July 1, 1863. General Lee planned an assault for the second day that would feature Longstreet's Corps attacking northeast up the Emmitsburg Road into the Union left flank. Hood was dissatisfied with his assignment in the assault because it would face difficult terrain in the boulder-strewn area known as the Devil's Den. He requested permission from Longstreet to move around the left flank of the Union army, beyond the mountain known as (Big) Round Top, to strike the Union in their rear area. Longstreet refused permission, citing Lee's orders, despite repeated protests from Hood. Yielding to the inevitable, Hood's division stepped off around 4 p.m. on July 2, but a variety of factors caused it to veer to the east, away from its intended direction, where it would eventually meet with Union forces at Little Round Top. Just as the attack was starting, however, Hood was the victim of an artillery shell exploding over his head, severely damaging his left arm, which incapacitated him. (Although the arm was not amputated, he was unable to make use of it for the rest of his life.) His ranking brigade commander, Brig. Gen. Evander M. Law, assumed command of the division, but confusion as to orders and command status dissipated the direction and strength of the Confederate attack, significantly affecting the outcome of the battle.

Hood recuperated in Richmond, Virginia, where he made a social impression on the ladies of the Confederacy. In August 1863, famous diarist Mary Chesnut wrote of Hood:

When Hood came with his sad Quixote face, the face of an old Crusader, who believed in his cause, his cross, and his crown, we were not prepared for such a man as a beau-ideal of the wild Texans. He is tall, thin, and shy; has blue eyes and light hair; a tawny beard, and a vast amount of it, covering the lower part of his face, the whole appearance that of awkward strength. Some one said that his great reserve of manner he carried only into the society of ladies. Major [Charles S.] Venable added that he had often heard of the light of battle shining in a man's eyes. He had seen it once—when he carried to Hood orders from Lee, and found in the hottest of the fight that the man was transfigured. The fierce light of Hood's eyes I can never forget.

Hood was involved in an embarrassing incident when he became convinced that the prettiest girl in Richmond society was in love with him. He promptly proposed and she promptly refused.[4]

Chickamauga

Meanwhile, in the Western Theater, the Confederate army under General Braxton Bragg was faring poorly. Lee dispatched Longstreet's Corps to Tennessee and Hood was able to rejoin his men on September 18. At the Battle of Chickamauga, Hood's division broke the Federal line at the Brotherton Cabin, which led to the defeat of General William Rosecrans's Union army. However, Hood was once again wounded severely, and his right leg was amputated four inches below the hip. His condition was so grave that the surgeon sent his severed leg along with Hood in the ambulance, assuming that they would be buried together. Because of Hood's bravery at Chickamauga, Longstreet recommended that he be promoted to lieutenant general as of that date, September 20, 1863.

During Hood's second recuperation in Richmond that fall, he befriended Confederate President Jefferson Davis, who would subsequently promote him to a more important role.

Hood would be assigned to serve under Joseph E. Johnston after the latter had replaced Bragg to assume command of the Army of Tennessee.[5]

Commander, Army of Tennessee

In the spring of 1864, the Confederate Army of Tennessee, under Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, was engaged in a campaign of maneuver against William T. Sherman, who was driving from Chattanooga toward Atlanta. During the campaign, Hood sent the government in Richmond letters very critical of Johnston's conduct (actions that were considered highly improper for a man in his position). On July 17, 1864, just before the Battle of Peachtree Creek, Jefferson Davis lost patience with Johnston's strategy of withdrawals and relieved him. Hood, commanding a corps under Johnston, was promoted to the temporary rank of full general on July 18, and given command of the army just outside the gates of Atlanta. At 33, Hood was the youngest man on either side of the war to be given command of an army. Robert E. Lee counseled Davis against this choice, supposedly saying that Hood was "all lion, no fox." (Hood's temporary appointment as a full general was never confirmed by the Senate. His commission as a lieutenant general resumed on January 23, 1865.[6]) Hood conducted the remainder of the Atlanta Campaign with the strong aggressive actions for which he was famous. He launched four major offensives that summer in an attempt to break Sherman's siege of Atlanta, starting almost immediately with Peachtree Creek. All of the offensives failed, with significant Confederate casualties. After failure resulted at Jonesboro, Hood realized he could no longer hold his position. Finally, on September 2, 1864, Hood evacuated the city of Atlanta, burning as many military supplies and installations as possible.

As Sherman regrouped in Atlanta, preparing for his March to the Sea, Hood and Jefferson Davis attempted to devise a strategy to defeat him. Their plan was to attack Sherman's lines of communications from Chattanooga and to move north through Alabama and into central Tennessee, assuming that Sherman would be threatened and follow. Hood's hope was that he could maneuver Sherman into a decisive battle, defeat him, recruit additional forces in Tennessee and Kentucky, and pass through the Cumberland Gap to come to the aid of Robert E. Lee, who was besieged at Petersburg. Sherman did not cooperate, however. Instead, he sent Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas to take control of the Union forces in Tennessee and coordinate the defense against Hood, while the bulk of Sherman's forces prepared to march toward Savannah.

Hood's Tennessee Campaign lasted from September to December 1864, comprising seven battles and hundreds of miles of marching. In November, Hood led his troops across the Tennessee River towards Nashville. After failing to defeat a large part of the Union Army of the Ohio under Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield at Spring Hill, Tennessee, on November 29, the next day at the Battle of Franklin his troops were unsuccessful in their attempt to breach the defensive Union breastworks and they allowed the Union force to withdraw unimpeded toward Nashville. Two weeks later, George Thomas defeated him again at the Battle of Nashville, in which most of his army was wiped out, one of the most significant Confederate battle losses in the Civil War. After the catastrophe of Nashville, the remnants of the Army of Tennessee retreated to Mississippi and Hood resigned his temporary commission as a full general as of January 23, 1865, reverting back to lieutenant general.[7]

Near the end of the war, Jefferson Davis ordered Hood to travel to Texas to raise another army. Before he could arrive, however, General Edmund Kirby Smith surrendered his Texas forces to the Union and Hood surrendered himself in Natchez, Mississippi, where he was paroled on May 31, 1865.

Postbellum career

After the war, Hood moved to New Orleans, Louisiana, and became a cotton broker and worked as a President of the Life Association of America, an insurance business. In 1868, he married New Orleans native Anna Marie Hennen, with whom he would father eleven children, including three pairs of twins, over ten years. He also served the community in numerous philanthropic endeavors, as he assisted in fund raising for orphans, widows, and wounded soldiers left behind from the ravages of war. His insurance business was ruined by a yellow fever epidemic in New Orleans during the winter of 1878–79 and he succumbed to the disease himself, dying just days after his wife and oldest child, leaving ten destitute orphans, who were adopted by families in Louisiana, Mississippi, Georgia, Kentucky, and New York.

Legacy

Hood was known for his aggressive maneuvers and was an excellent commander early in the war, when he led smaller forces. Under Lee's command, Hood was capable of aiding the army in major victories, most notably at Antietam, where he helped prevent Lee's forces from suffering a premature defeat. Hood was much less efficient when given command over more troops. He would prove inept as a general, even seemingly ordering the sacrifice of his men in the disastrous final days of his military career. He would go on to defend his leadership abilities and battlefield decisions after the fact in an effort to redeem himself for major failures he suffered during the war.

In memoriam

John Bell Hood is buried in the Hennen family tomb at Metairie Cemetery, New Orleans. He is memorialized by Hood County, Texas, and the U.S. Army installation, Fort Hood, Texas.

Stephen Vincent Benét's poem, "Army of Northern Virginia"[8] included a poignant passage about Hood:

- Yellow-haired Hood with his wounds and his empty sleeve,

- Leading his Texans, a Viking shape of a man,

- With the thrust and lack of craft of a berserk sword,

- All lion, none of the fox.

- When he supersedes

- Joe Johnston, he is lost, and his army with him,

- But he could lead forlorn hopes with the ghost of Ney.

- His bigboned Texans follow him into the mist.

- Who follows them?

After the defeats in the Franklin-Nashville Campaign, Hood's troops sang with wry humor a verse about him as part of the song The Yellow Rose of Texas:

- My feet are torn and bloody,

- My heart is full of woe,

- I'm going back to Georgia

- To find my uncle Joe.

- You may talk about your Beauregard,

- You may sing of Bobby Lee,

- But the gallant Hood of Texas

- He played hell in Tennessee.

In popular culture

- In the movies Gods and Generals and Gettysburg, Hood was portrayed by actor Patrick Gorman, a man considerably older looking than Hood, who was only 32 years old at the time.

Notes

- ↑ John H. Eicher and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2001), 302.

- ↑ Sam Hood, John Bell Hood. Retrieved September 6, 2007.

- ↑ James Meredith, "John Bell Hood," in Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, eds. David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000). ISBN 9781576070666

- ↑ Mike West, 45th Tennessee spared at Battle of Franklin. Retrieved September 17, 2007.

- ↑ Meredith, 997.

- ↑ Eicher, 303.

- ↑ Meredith, 998.

- ↑ Stephen Vincent Benét, Army of Northern Virginia. Retrieved September 17, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Benét, Stephen Vincent. Army of Nortern Virginia. Retrieved September 17, 2007.

- Chesnut, Mary. Diary of Mary Chesnut. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1905.

- Eicher, John H. and David J. Civil War High Commands. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3

- Hood, Sam. John Bell Hood, Confederate General at Gettysburg, Chickamauga, Atlanta Campaign, Nashville Campaign. Retrieved September 6, 2007.

- JohnBellHood.org. John Bell Hood Retrieved September 6, 2007.

- Meredith, James. "John Bell Hood." In Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler, 995-98. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04758-X

- McMurry, Richard M. John Bell Hood and the War for Southern Independence. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992. ISBN 0-8032-8191-9

- Tagg, Larry. The Generals of Gettysburg. El Dorado Hills: Savas Publishing, 1998. ISBN 1-882810-30-9

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 0-8071-0823-5

- West, Mike. "45th Tennessee spared at Battle of Franklin." Mufreesboro Post.

- University of Texas. John Bell Hood. Retrieved September 6, 2007.

External links

All links retrieved January 30, 2025.

- John Bell Hood posts on The Battle of Franklin blog

- Entry for General John B. Hood from the Biographical Encyclopedia of Texas published 1880, hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- Charging into Battle with Hood's Texas Brigade a Primary Source Adventure, a lesson plan hosted by The Portal to Texas History.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.