Seven Days Battles

| The Seven Days Battles | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

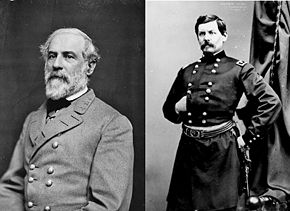

Lee and McClellan of the Seven Days | |||||||

| |||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

| United States of America | Confederate States of America | ||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| George B. McClellan | Robert E. Lee | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 104,100[1] | 92,000[2] | ||||||

| Casualties | |||||||

| 15,855 (1,734 killed, 8,066 wounded, 6,055 missing/captured)[3] | 20,204 (3,494 killed, 15,758 wounded, 952 missing/captured)[4] | ||||||

The Seven Days Battles was a series of six major battles over the seven days, from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia, in the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, away from Richmond and into a retreat down the Virginia Peninsula. The series of battles is sometimes known erroneously as the Seven Days Campaign, but it was actually the culmination of the Peninsula Campaign, not a separate campaign in its own right.

The Seven Days Battles began with a Union attack in the minor Battle of Oak Grove on June 25, 1862, but McClellan quickly lost the initiative, as Lee began a series of attacks at Beaver Dam Creek on June 26, Gaines' Mill on June 27, the minor actions at Garnett's and Golding's Farm on June 27 and June 28, and the attack on the Union rear guard at Savage's Station on June 29. McClellan's Army of the Potomac continued its retreat toward the safety of Harrison's Landing on the James River. Lee's final opportunity to intercept the Union Army was at the Battle of Glendale on June 30, but poorly executed orders allowed his enemy to escape to a strong defensive position on Malvern Hill. At the Battle of Malvern Hill on July 1, Lee launched futile frontal assaults and suffered heavy casualties in the face of strong infantry and artillery defenses.

The Seven Days ended with McClellan's army in relative safety next to the James River, having suffered almost 16,000 casualties during the retreat. Lee's army, which had been on the offensive during the Seven Days, lost over 20,000. As Lee became convinced that McClellan would not resume his threat against Richmond, he moved north for the Northern Virginia Campaign and the Maryland Campaign. McClellan's movements were characterized by gross overestimates of his foe that resulted in a hesitance to attack promptly.[5] Lee's success in this campaign certainly prolonged the war, the bloodiest in American history. On the other hand, when the Confederate States of America were ultimately defeated, the fact that their troops had conducted themselves well against the better trained and equipped North, enabled the vanquished to retain some sense of dignity and pride. Without this, the task of rebuilding the nation after the war would have been much more difficult.

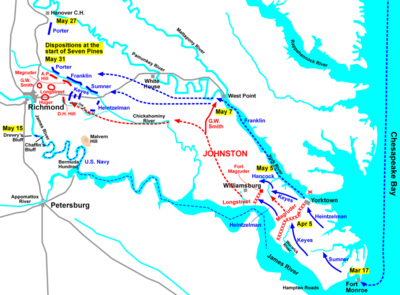

Start of the Peninsula Campaign

The Peninsula Campaign was the unsuccessful attempt by McClellan to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond and end the war. It started in March 1862, when McClellan landed his Army of the Potomac at Fort Monroe on the tip of the Virginia Peninsula. Moving slowly and cautiously up the peninsula, McClellan fought a series of minor battles and sieges against Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, who was equally cautious in the defense of his capital, retreating step by step to within six miles (10 km) of Richmond. There, the Battle of Seven Pines (also known as the Battle of Fair Oaks) took place on May 31 and June 1, 1862. It was a tactical draw, but it had wide-ranging consequences for the warâJohnston was wounded and replaced by the much more aggressive Gen. Robert E. Lee. Lee spent almost a month extending his defensive lines and organizing his Army of Northern Virginia; McClellan accommodated this by sitting passively to his front until the start of the Seven Days. Lee, who had developed a reputation for caution early in the war, knew he had no numerical superiority over McClellan, but he planned an offensive campaign that marked the aggressive nature by which he was characterized for the remainder of the war.

Opposing forces

Almost 200,000 men were in the armies that fought in the Seven Days Battles, although the inexperience or caution of the generals involved often prevented the appropriate concentration of forces and mass necessary for decisive tactical victories.

On the Confederate side, Lee's Army of Northern Virginia was larger than the one he inherited from Johnston, and, at about 92,000 men, larger than any army he commanded for the rest of the war.

- Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson, having just arrived from his victories in the Valley Campaign, commanded a force consisting of his own division (now commanded by Brig. Gen. Charles S. Winder) and those of Maj. Gen. Richard S. Ewell, Brig. Gen. William H. C. Whiting, and Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill.

- Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill's "Light Division" (which was so named because it traveled light and was able to maneuver and strike quickly) consisted of the brigades of Brig. Gens. Charles W. Field, Maxcy Gregg, Joseph R. Anderson, Lawrence O'Bryan Branch, James J. Archer, and William Dorsey Pender.

- Maj. Gen. James Longstreet's division consisted of the brigades of Brig. Gens. James L. Kemper, Richard H. Anderson, George E. Pickett, Cadmus M. Wilcox, Roger A. Pryor, and Winfield Scott Featherston. Longstreet also had operational command over Hill's Light Division.

- Maj. Gen. John B. Magruder commanded the divisions of Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws, Brig. Gen. David R. Jones, and Magruder's own division, commanded by Brig. Gen. Howell Cobb.

- Maj. Gen. Benjamin Huger's division consisted of the brigades of Brig. Gens. William Mahone, Ambrose R. Wright, Lewis A. Armistead, and Robert Ransom, Jr.

- Maj. Gen. Theophilus H. Holmes's division consisted of the brigades of Brig. Gens. Junius Daniel, John G. Walker, Henry A. Wise, and the cavalry brigade of Brig. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart.

McClellan's Army of the Potomac, with approximately 104,000 men, was organized largely as it had been at Seven Pines.

- II Corps, Brig. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner commanding: Divisions of Brig. Gens. Israel B. Richardson and John Sedgwick.

- III Corps, Brig. Gen. Samuel P. Heintzelman commanding: Divisions of Brig. Gens. Joseph Hooker and Philip Kearny.

- IV Corps, Brig. Gen. Erasmus D. Keyes commanding: Divisions of Brig. Gens. Darius N. Couch and John J. Peck.

- V Corps, Brig. Gen. Fitz John Porter commanding: Divisions of Brig. Gens. George W. Morrell, George Sykes, and George A. McCall.

- VI Corps, Brig. Gen. William B. Franklin commanding: Divisions of Brig. Gens. Henry W. Slocum and William F. âBaldyâ Smith.

- Reserve forces included the cavalry reserve under Brig. Gen. Philip St. George Cooke (Jeb Stuart's father-in-law) and the supply base at White House Landing under Brig. Gen. Silas Casey.

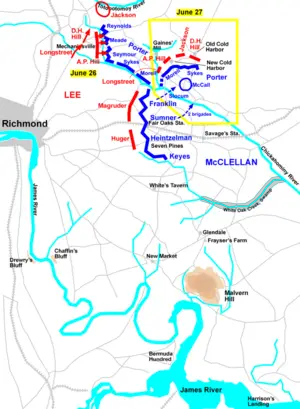

Lee's plan

Similar to Johnston's plan at Seven Pines, Lee's attack plan was complex and required expert coordination and execution by all of his subordinates. It was developed at a meeting on June 23. Union forces to his front consisted of about 30,000 men under Porter on the northern side of the Chickahominy River; the remaining 60,000 on the front were scattered to the south. He intended for Jackson to attack Porter's right flank early on the morning of June 26, and A.P. Hill would move from Meadow Bridge to Beaver Dam Creek, which flows into the Chickahominy, advancing on the Federal trenches. (Lee expected, somewhat hopefully, that Porter would evacuate his trenches under pressure, obviating the need for a direct frontal assault.) Following this, Longstreet and D.H. Hill would pass through Mechanicsville and join the battle. Huger and Magruder would provide diversions on their fronts to distract McClellan as to Lee's real intentions. Lee hoped that Porter would be overwhelmed from two sides by the mass of 65,000 men, and Lee's two leading divisions would move on Cold Harbor and cut McClellan's communications with White House Landing. However, the execution of the plan was seriously bungled.

Battles

- Battle of Oak Grove (June 25, 1862)

- A minor clash that preceded the major battles of the Seven Days. Attempting to move siege guns closer to Richmond and drive back Confederate pickets, Union forces under Hooker attacked through a swamp without affecting the Confederate assault that started the next morning.

- Battle of Beaver Dam Creek (June 26)

- Beaver Dam Creek, or Mechanicsville, was the first major battle of the Seven Days. Jackson moved slowly without contact, and by 3 p.m., A.P. Hill grew impatient and began his attack without orders. Two hours of heavy fighting between Hill and McCall's division resulted. Porter reinforced McCall with the brigades of Brig. Gens. John H. Martindale and Charles Griffin, and he extended and strengthened his right flank. He fell back and concentrated along Beaver Dam Creek and Ellerson's Mill. Jackson and his command arrived late in the afternoon but, unable to find A.P. Hill or D.H. Hill, did nothing. Although a major battle was raging within earshot, he ordered his troops to bivouac for the evening. A.P. Hill, with Longstreet and D.H. Hill behind him, continued his attack, despite orders from Lee to hold his ground. His assault was beaten back with heavy casualties. Despite being a Union tactical victory, it was the start of a strategic debacle. McClellan, believing that the diversions by Huger and Magruder south of the river meant that he was seriously outnumbered, withdrew to the southeast to evade the imaginary threat of being surrounded and never regained the initiative.[6]

- Battle of Gaines' Mill (June 27)

- Lee continued his offensive, launching the largest Confederate attack of the war. (It occurred in almost the same location as the 1864 Battle of Cold Harbor and had similar numbers of total casualties.) The Union forces were concentrated into a semicircle with Porter collapsing his line into an east-west salient north of the river and the corps south of the river remaining in their original positions. Porter was ordered by McClellan to hold Gaines' Mill at all costs so that the army could change its base of supply to the James River. Several of his subordinates urged him to attack Magruder, but he still feared the vast numbers of Confederates he believed to be before him. A.P. Hill resumed his attack across Beaver Dam Creek early in the morning, but found the line lightly defended. By early afternoon, he ran into strong opposition by Porter, deployed along Boatswain's Creek, and the swampy terrain was a major obstacle against the attack. As Longstreet arrived to the south of A.P. Hill, he saw the difficulty of attacking over such terrain and delayed until Jackson could attack on Hill's left. Once again, however, Jackson was late. D.H. Hill attacked the Federal right and was held off by Sykes; he backed off to await Jackson's arrival. Longstreet was ordered to conduct a diversionary attack to stabilize the lines until Jackson could arrive and attack from the north. In that attack, Pickett's brigade was beaten back under severe fire with heavy losses. Jackson finally arrived at 3 p.m. and was completely disoriented following a day of pointless marching and counter-marching. Porter's line was saved by Slocum's division moving into position. Shortly after dark, the Confederates mounted another attack, poorly coordinated, but this time collapsing the Federal line. Brig. Gen. John Bell Hood's Texas Brigade opened a gap in the line, as did Pickett's Brigade on its second attempt of the day. Once again, Magruder was able to continue fooling McClellan south of the river and occupying 60,000 Federal troops while the heavier action occurred north of the river. By 4 a.m. on June 28, Porter withdrew across the Chickahominy, burning the bridges behind him. The planned attack on the Confederate capital at Richmond was forfeited for the time being.

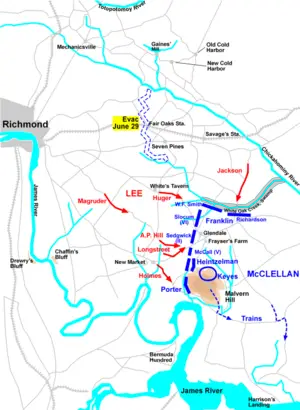

That night, McClellan ordered his entire army to withdraw to a secure base at Harrison's Landing on the James. His actions have puzzled military historians ever since. He was actually in a strong position, having withstood strong Confederate attacks, while having deployed only one of his five corps in battle. Porter had performed well against heavy odds. Furthermore, McClellan was aware that the War Department had created a new Army of Virginia and ordered it to be sent to the Peninsula to reinforce him. But Lee had unnerved him, and he surrendered the initiative. He sent a telegram to the Secretary of War that included the statement: "If I save this Army now I tell you plainly that I owe no thanks to you or any other persons in Washingtonâyou have done your best to sacrifice this Army." (The military telegraph department chose to omit this sentence from the copy given to the Secretary.) McClellan ordered Keyes's IV Corps to move west of Glendale and protect the army's withdrawal, and Porter was to move to the high ground at Malvern Hill to develop defensive positions. The supply trains were ordered to move south toward the river. McClellan departed for Harrison's Landing without specifying any exact routes of withdrawal and without designating a second-in-command. For the remainder of the Seven Days, he had no direct command of the battles.

- Battle of Garnett's & Golding's Farm (June 27âJune 28)

- A minor Confederate demonstration and attack south of the river, a continuation of the action at Gaines' Mill. As an outgrowth of Magruder's demonstrations, the brigades of Col. George T. Anderson and Brig. Gen. Robert Toombs engaged in some heavy fighting against the brigade of Brig. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock. The attacks were easily repulsed but served to further unnerve McClellan. Toombs resumed the attack the following morning, and although achieving more success than on June 27, his men withdrew under heavy artillery fire from Garnett's farm.

- Battle of Savage's Station (June 29)

- As the Union corps operated without direction from McClellan's headquarters, they approached positions near Savage's Station on the Richmond & York River Railroad, preparing for the difficult march through and around the White Oak Swamp. Magruder ran into the rearguard of the Union force at the station. He was slow in organizing an attack but was able to do so against Sumner's corps and Baldy Smith's division by mid-afternoon. He was expecting to be assisted by Jackson at any moment, but for the third time in the campaign, Jackson failed to arrive. He had spent the day of June 29 resting his men and rebuilding a bridge over the Chickahominy, even though a suitable ford was available nearby. After his troops had advanced an arduous 5 miles (8 km) Magruder's assaults were repulsed, and the Union corps were able to escape, principally because of Jackson's procrastination. By noon on June 30, all of the Army of the Potomac had cleared White Oak Swamp Creek, but because of the uncoordinated withdrawal, a bottleneck developed at Glendale.

- Battle of White Oak Swamp (June 30)

- The Union rearguard under Franklin stopped Jackson's divisions at the White Oak Bridge crossing, resulting in an artillery duel, while the main battle raged two miles (3 km) farther south at Glendale. White Oak Swamp is often considered to be part of the Glendale engagement.

- Battle of Glendale (June 30)

- Lee ordered his army to converge on the bottlenecked Union forces between the White Oak Swamp and the crossroads at Frayser's Farm, which is another name for the battle. Once again, Lee's plan was poorly executed. Huger was slowed by obstructions along the Charles City Road and failed to participate in the battle. Magruder marched around indecisively and eventually joined Holmes in an unsuccessful maneuver against Porter at Malvern Hill. Jackson again moved slowly and spent the entire day north of the creek, making only feeble efforts to cross and attack Franklin (the Battle of White Oak Swamp). Lee, Longstreet, and visiting Confederate President Jefferson Davis were observing the action on horseback when they came under heavy artillery fire, and the party withdrew with two men wounded and three horses killed. Because of the setbacks, only A.P. Hill and Longstreet were able to attack in the battle. Longstreet performed poorly, sending in brigades in a piecemeal fashion, rather than striking with concentrated force in the manner for which he was known later in the war. They struck George McCall's division and forced it back, but the penetration was soon sealed off by Union reinforcements. McCall was captured during the battle; Meade, Sumner, Anderson, Featherston, and Pender were wounded. Lee would have only one more opportunity to intercept McClellan's army before it reached the safety of the river.

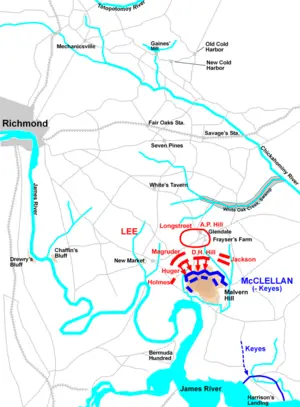

- Battle of Malvern Hill (July 1)

- The final battle of the Seven Days was the first in which the Union Army occupied favorable ground. Malvern Hill offered good observation and artillery positions. The open fields to the north could be swept by fire from the 250 guns placed by Col. Henry J. Hunt, McClellan's chief of artillery. Major General D.H. Hill famously said of the engagement, "It wasn't war; it was murder."

Beyond this space, the terrain was swampy and thickly wooded. Rather than flanking the position, Lee attacked it directly, hoping that his artillery would clear the way for a successful infantry assault (just as he miscalculated the following year in Pickett's Charge at Gettysburg). The Union artillery was superior in position and expertise, and their counter-battery fire disabled numerous Confederate guns. Lee canceled his attack, but late in the afternoon he observed Union troop movements and, assuming that they were part of a withdrawal, ordered another attack. It was a poorly managed, piecemeal affair with separate attacks by D.H. Hill, Jackson, and finally Huger. A.P. Hill and Longstreet were not deployed. Porter, the senior man on the hill during McClellan's absence, repulsed the attacks with ease. Lee's army suffered over 5,000 casualties (versus 3,200 Union) in this wasted effort and withdrew to Richmond, while the Union Army completed its retreat to Harrison's Landing, rather than counterattack as McClellan's subordinates had suggested.[7]

Aftermath

The Seven Days Battles ended the Peninsula Campaign. The Army of the Potomac encamped around Berkeley Plantation, birthplace of William Henry Harrison. With its back to the James River, the army was protected by Union gunboats, but suffered heavily from heat, humidity, and disease. In August, they were withdrawn by order of President Abraham Lincoln to reinforce the Army of Virginia in the Northern Virginia Campaign and the Second Battle of Bull Run.

The casualties to both sides were dreadful. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia suffered about 20,000 casualties (3,494 killed, 15,758 wounded, and 952 captured or missing) out of a total of over 90,000 soldiers during the Seven Days, losing about one-fourth of his total force. McClellan reported casualties of about 16,000 (1,734 killed, 8,062 wounded, and 6,053 captured or missing) out of a total of 105,445. Despite their victory, many Confederates were stunned by the losses.

The effects of the Seven Days Battles were widespread. After a successful start on the Peninsula that foretold an early end to the war, Northern morale was crushed by McClellan's retreat. McClellan would stall until late July and then move his army to Fort Monroe to regroup. Despite heavy casualties and clumsy tactical performances by Lee and his generals, Confederate morale skyrocketed, and Lee was emboldened to continue his aggressive strategy through Second Bull Run and the Maryland Campaign. McClellan's previous position as general-in-chief of all the Union armies, vacant since March, was filled on July 11, 1862, by Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, although McClellan did retain command of the Army of the Potomac. Lee reacted to the performances of his subordinates by a reorganization of his army and by forcing the reassignment of Holmes and Magruder out of Virginia.

Notes

- â Stephen W. Sears, To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign (New York: Ticknor and Fields, 1992), 195.

- â Sears, 195.

- â Sears, 345.

- â Sears, 343.

- â Jospeh M. McCarthy, "Seven Days' Battles," in Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, eds. David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000), 1732.

- â McCarthy, 1734.

- â McCarthy, 1735.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bailey, Ronald H. Forward to Richmond: McClellan's Peninsular Campaign. Alexandria: Time-Life Books, 1983. ISBN 0-8094-4720-7

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5

- Esposito, Vincent J. West Point Atlas of American Wars. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1959.

- McCarthy, Jospeh M. "Seven Days' Battles." In Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History. Edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler, 1732-1735. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04758-X

- Sears, Stephen W. To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign. New York: Ticknor and Fields, 1992. ISBN 0-89919-790-6

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.