Division of labor

Division of Labor is the specialization of cooperative labor in specific, circumscribed tasks and roles, intended to increase efficiency of output. It has been present in most cultures throughout human history. In its most essential form, there is a division of based on gender, such as in hunter-gatherer societies where men hunt and women gather food while taking care of children. The growth of a more and more complex division of labor is closely associated with the growth of trade, the rise of capitalism, and of the complexity of industrialization processes. While such division of labor is often viewed in a negative light, as leading to an unequal distribution of reward for effort, it nonetheless must be recognized as an essential efficiency in larger societies. The challenge in developing harmony and prosperity for all is how to maintain division of labor without attaching different value to those performing different tasks.

Overview

The division of labor can apply to any field. Division of labor may be applied to the differences in work done by different genders, workers in an industrial assembly line, to different social classes or professions within a society. The division of labor can also be abstracted to a global level and seen through the lens of globalization as countries have followed the mold of David Ricardo's comparative advantage and attempted to specialize in producing those goods or services they are best placed to produce.

Theories

The concept of dividing labor for increased efficiency has existed for a long time in human history. Theories of the benefits associated with division of labor have been refined over time.

Plato

In Plato's Republic we are instructed that the origin of the state lies in that "natural" inequality of humanity that is embodied in the division of labor:

Well then, how will our state supply these needs? It will need a farmer, a builder, and a weaver, and also, I think, a shoemaker and one or two others to provide for our bodily needs. So that the minimum state would consist of four or five men.[1]

Xenophon

Xenophon, writing in the fourth century B.C.E. makes a passing reference to division of labor in his Cyropaedia (also known as Education of Cyrus).

Just as the various trades are most highly developed in large cities, in the same way food at the palace is prepared in a far superior manner. In small towns the same man makes couches, doors, plows and tables, and often he even builds houses, and still he is thankful if only he can find enough work to support himself. And it is impossible for a man of many trades to do all of them well. In large cities, however, because many make demands on each trade, one alone is enough to support a man, and often less than one: for instance one man makes shoes for men, another for women, there are places even where one man earns a living just by mending shoes, another by cutting them out, another just by sewing the uppers together, while there is another who performs none of these operations but assembles the parts, Of necessity, he who pursues a very specialized task will do it best.[2]

William Petty

Sir William Petty was the first modern writer to take note of division of labor, showing its existence and usefulness in Dutch shipyards. Classically the workers in a shipyard would build ships as units, finishing one before starting another. The Dutch, however, had it organized with several teams each doing the same tasks for successive ships.

Petty applied this principle to his survey of Ireland. His breakthrough was to divide up the work so that large parts of it could be done by people with no extensive training.[3]

Bernard de Mandeville

Bernard de Mandeville discussed the matter in the second volume of The Fable of the Bees. This elaborates many matters raised by the original poem about a "Grumbling Hive:"

But if one will wholly apply himself to the making of Bows and Arrows, whilst another provides Food, a third builds Huts, a fourth makes Garments, and a fifth Utensils, they not only become useful to one another, but the Callings and Employments themselves will in the same Number of Years receive much greater Improvements, than if all had been promiscuously follow’d by every one of the Five.[4]

David Hume

David Hume talked about "partition of employments" in A Treatise of Human Nature (1739):

When every individual person labors a-part, and only for himself, his force is too small to execute any considerable work; his labor being employ’d in supplying all his different necessities, he never attains a perfection in any particular art; and as his force and success are not at all times equal, the least failure in either of these particulars must be attended with inevitable ruin and misery. Society provides a remedy for these three inconveniences. By the conjunction of forces, our power is augmented: By the partition of employments, our ability encreases: And by mutual succour we are less expos’d to fortune and accidents. ’Tis by this additional force, ability, and security, that society becomes advantageous.[5]

Henri Louis Duhamel du Monceau

In his additions to l'Art de l'Épinglier (The Art of the Pin-Maker) in 1761, Henri Louis Duhamel du Monceau wrote about the division of labor:

There is nobody who is not surprised of the small price of pins; but we shall be even more surprised, when we know how many different operations, most of them very delicate, are mandatory to make a good pin. We are going to go through these operations in a few words to stimulate the curiosity to know their detail; this enumeration will supply as many articles which will make the division of this labor. […] The first operation is to have brass go through the drawing plate to calibrate it.[6]

Adam Smith

In the first sentence of An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), Adam Smith foresaw the essence of industrialism by determining that division of labor represents a qualitative increase in productivity. His example was the making of pins. Unlike Plato, Smith did not regard the division of labor as a consequence of human inequality but famously argued that the difference between a street porter and a philosopher was as much a consequence of the division of labor as its cause. Therefore, while for Plato the level of specialization determined by the division of labor was externally determined, for Smith it was the dynamic engine of economic progress.

However, in a further chapter of the same book Smith criticized the division of labor saying it leads to a "mental mutilation" in workers; they become ignorant and insular as their working lives are confined to a single repetitive task. The contradiction has led to some debate over Smith's opinion of the division of labor.

Specialization and concentration of workers on their single subtasks often leads to greater skill and greater productivity on their particular subtasks than would be achieved by the same number of workers each carrying out the original broad task.

Smith saw the importance of matching skills with equipment—usually in the context of an organization. For example, pin makers were organized with one making the head, another the body, each using different equipment. Similarly he emphasized that a large number of skills, used in cooperation and with suitable equipment, were required to build a ship.

In modern economic discussion the term "human capital" would be used. Smith's insight suggests that the huge increases in productivity obtainable from technology or technological progress are possible because human and physical capital are matched, usually in an organization.[7]

Karl Marx

Increasing specialization may also lead to workers with poorer overall skills and a lack of enthusiasm for their work. This viewpoint was extended and refined by Karl Marx. He described the process as alienation; workers become more and more specialized and work repetitious which eventually leads to complete alienation. Marx wrote that "with this division of labor," the worker is "depressed spiritually and physically to the condition of a machine." He believed that the fullness of production is essential to human liberation and accepted the idea of a strict division of labor only as a temporary necessary evil.[8]

Marx's most important theoretical contribution was his sharp distinction between the "social" division and the "technical" or economic division of labor. That is, some forms of labor co-operation are due purely to "technical necessity," but others are purely a result of a "social control" function related to a class and status hierarchy. If these two divisions are conflated, it might appear as though the existing division of labor is technically inevitable and immutable, rather than (in good part) socially constructed and influenced by power relationships.

It may be, for example, that it is technically necessary that both pleasant and unpleasant jobs must be done by a group of people. But from that fact alone, it does not follow that any particular person must do any particular (pleasant or unpleasant) job. If particular people are assigned the unpleasant jobs and others the pleasant jobs, this cannot be explained by technical necessity; it is a socially made decision, which could be made using a variety of different criteria. Or, the tasks could be rotated periodically, ensuring that all people spend time on both pleasant and unpleasant tasks.

In Marx's imagined communist society, the division of labor is transcended, meaning that balanced human development occurs where people fully express their nature in the variety of creative work that they do.

Émile Durkheim

Émile Durkheim wrote that as societies advanced they came to resemble complex machines and naturally adopted principles of the division of labor.[9] In early societies, people have a common consciousness as they all perform identical labor so they can identify strongly with one another. As society grows more complex and people begin to specialize in their lines of work, they become alienated from one another.

Max Weber

In the early 1900s, Max Weber designed a rational organizational form, called a bureaucracy. Among the characteristics of this "ideal" organization were specialization, division of labor, and a hierarchical organizational design. Many aspects of modern public administration are attributed to Max Weber and his theory of bureaucracy. A classic, hierarchically organized civil service of the continental type is called "Weberian civil service," although this is only one ideal type of public administration and government described in his magnum opus, Economy and Society. In this work, Weber outlined his description of rationalization (of which bureaucratization is a part) as a shift from a value-oriented organization and action (traditional authority and charismatic authority) to a goal-oriented organization and action (legal-rational authority). The result, according to Weber, is a "polar night of icy darkness," in which increasing rationalization of human life traps individuals in an "iron cage" of rule-based, rational control.

Weber described the "ideal type" bureaucracy in positive terms, considering it to be a more rational and efficient form of organization than the alternatives that preceded it, which he characterized as "charismatic domination" and "traditional domination." According to his terminology, bureaucracy is part of legal domination. However, he also emphasized that bureaucracy becomes inefficient when a decision must be adapted to an individual case.

According to Weber, the attributes of modern bureaucracy include its impersonality, concentration of the means of administration, a leveling effect on social and economic differences, and implementation of a system of authority that is practically indestructible. Thus, bureaucracy goes beyond division of labor in a broad sense, although that is a necessary condition for the existence of bureaucratic systems. It involves precise, detailed definitions of the duties and responsibilities of each person or office. Administrative regulations determine areas of responsibility and control the allocation of tasks to each area.

Ludwig von Mises

Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises criticized Karl Marx's work. He argued that the gains accruing from the division of labor by far outweigh the costs; that it is fully possible to achieve balanced human development within capitalism, and that alienation is more a romantic fiction. After all, work is not all there is; there is also leisure time.[10]

Frederick Winslow Taylor

The division of labor reached the level of a scientifically-based management practice with the time and motion studies associated with Taylorism, which originated in Frederick Winslow Taylor's work The Principles of Scientific Management. Taylor believed that decisions based upon tradition and rules of thumb should be replaced by precise procedures developed after careful study of an individual at work. He is most remembered for developing the time and motion study, which actually combines Taylor's studies of the time involved in the component parts of each job with Frank Gilbreth's work on reducing the number of movements required to complete a job.

Taylor believed that the industrial management of his day was amateurish, that management could be formulated as an academic discipline, and that the best results would come from the partnership between a trained and qualified management and a cooperative and innovative workforce. Each side needed the other, and there was no need for trade unions. Taylor's scientific management consisted of four principles:

- Replace rule-of-thumb work methods with methods based on a scientific study of the tasks

- Scientifically select, train, and develop each employee rather than passively leaving them to train themselves

- Provide detailed instruction and supervision of each worker in the performance of that worker's discrete task

- Divide work nearly equally between managers and workers, so that the managers apply scientific management principles to planning the work and the workers actually perform the tasks

Taylor had very precise ideas about how to introduce his system:

It is only through enforced standardization of methods, enforced adaption of the best implements and working conditions, and enforced cooperation that this faster work can be assured. And the duty of enforcing the adaption of standards and enforcing this cooperation rests with management alone.[11]

Division according to gender

The clearest exposition of the principles of sexual division of labor across the full range of human societies can be summarized by a large number of logically complementary implicational constraints of the following form: If women of childbearing ages in a given community tend to do X (such as preparing soil for planting) they will also do Y (the planting) while for men the logical reversal in this example would be that if men plant they will prepare the soil.

Tasks more frequently chosen by women in these order relations are those more convenient in relation to childrearing.[12] This type of finding has been replicated in a variety of studies, including modern industrial economies. These entailments do not restrict how much work for any given task could be done by men (such as cooking) or by women (such as clearing forests) but are only least-effort or role-consistent tendencies. To the extent that women clear forests for agriculture, for example, they tend to do the entire agricultural sequence of tasks on those clearings. In theory, these types of constraints could be removed by provisions of child care, but ethnographic examples are lacking.

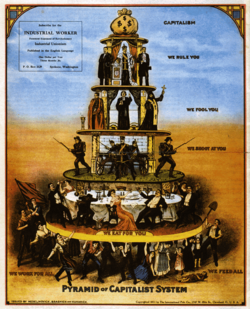

Division according to class

For most of recorded human history, societies have been agricultural and have existed with essentially two classes—those who owned productive agricultural land, and those who worked for landowners, with the landowning class arranging itself into a sometimes elaborate hierarchy, but without ever changing the essential power relationship of owner to worker. In the 1770s, when the term "social class" first entered the English lexicon, the concept of a "middle class" within that structure was also becoming very important. The Industrial Revolution allowed a much greater portion of the population time for the kind of education and cultural refinement once restricted to the European "leisure class" of large landholders. Also, the far greater distribution of news and liberal arts knowledge was making workers question and rebel against the privileges and religious assumptions of the leisure class.

Today, most talk of social class assumes three general categories: an upper class of powerful owners, a middle class of people who may not exert power over others but do control their own destiny through commerce or land ownership, and a lower class of people who own neither property nor stock in the corporate system, and who rely on wages from above for their livelihood.

Industrialization

The division of labor allowed for greater industrialization as the theories became manifest in assembly lines being used for mass production. The mass production system involves the production of large amounts of standardized products on production lines, and was popularized by Henry Ford as a tool for manufacturing his Model T automobiles. Mass production typically uses moving tracks or conveyor belts to move partially complete products to workers, who perform simple repetitive tasks to permit very high rates of production per worker, allowing the high-volume manufacture of inexpensive finished goods.

In a factory for a complex product, rather than one assembly line, there may be many auxiliary assembly lines feeding sub-assemblies (such as car engines or seats) to a backbone "main" assembly line. A diagram of a typical mass-production factory thus looks more like the skeleton of a fish than a single straight line. However, the principle of division of labor remains the essential foundation.

Modern debates

In the modern world, theorists of the division of labor are those involved in management and organization. In view of the global extremities of the division of labor, the question is often raised about what division of labor would be most ideal, beautiful, efficient, and just.

Labor hierarchy is to a great extent inevitable, simply because no one can do all tasks at once; but the way these hierarchies are structured can be influenced by a variety of different factors.

It is often agreed that the most equitable principle in allocating people within hierarchies is that of true (or proven) competency or ability. This important Western concept of meritocracy could be read as an explanation or as a justification of why a division of labor is the way it is.

In general, in capitalist economies, such things are not decided consciously. Different people try different things, and that which is most effective (produces the most and best output with the least input) will generally be adopted. Often techniques that work in one place or time do not work as well in another. This does not present a problem, as the only requirement of a capitalist system is that the value of the outputs exceed the value of the inputs.

Division of labor is thus seen to have both advantages and disadvantages. Some of each are listed below.

Advantages

- More efficient in terms of time

- Reduces the time needed for training because the task is simplified

- Increases productivity because training time is reduced and the worker is productive in a short amount of time

- Concentration on one repetitive task makes workers more skilled at performing that task

- Little time is spent moving between tasks so overall time wasted is reduced

- The overall quality of the product will increase bringing welfare gains to the consumer

Disadvantages

- Lack of motivation: The quality of labor decreases while absenteeism may rise

- Growing dependency: A break in production may cause problems to the entire process

- Loss of flexibility: Workers have limited knowledge while not many jobs opportunities are available

- Higher start-up costs: High initial costs necessary to buy the special machinery lead to a higher break-even point

Notes

- ↑ Plato, Republic (Hackett Publishing Company, 1992, ISBN 0872201368).

- ↑ M.I. Finley, The Ancient Economy (University of California Press, 1999, ISBN 0520219465), p. 135

- ↑ William Petty, The Political Anatomy of Ireland: With the Establishment for that Kingdom and Verbum Sapienti (Irish University Press, 1970, ISBN 0716500930).

- ↑ Bernard de Mandeville, The Fable of the Bees: And Other Writings (Hackett Publishing Company, 1997, ISBN 0872203743).

- ↑ David Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature (NuVision Publications, 2007, ISBN 1595478590).

- ↑ R. Réaumur and A. de Ferchault, Art de l'Épinglier avec des additions de M. Duhamel du Monceau et des remarques extraites des mémoires de M. Perronet, inspecteur général des Ponts et Chaussées (Paris: Saillant et Nyon, 1761).

- ↑ Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (University of Chicago Press, 1977, ISBN 0226763749).

- ↑ Karl Marx, Capital (Pluto Press, 2003, ISBN 074532049X).

- ↑ Émile Durkheim, The Division of Labor in Society (Free Press, 1997, ISBN 0684836386).

- ↑ David Ramsay Steele, From Marx to Mises: Post-Capitalist Society and the Challenge of Economic Calculation (Open Court, 1999, ISBN 0812690168).

- ↑ Frederick Taylor, Scientific Management (Routledge, 2003, ISBN 0415279836).

- ↑ Douglas R. White, Michael L. Burton, and Lilyan A. Brudner, Entailment Theory and Method: A Cross-Cultural Analysis of the Sexual Division of Labor, Behavior Science Research Vol 12, No 1, (1977). Retrieved December 20, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Braverman, Harry. Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Labor in the 20th Century. Monthly Review Press, 1998. ISBN 0853459401

- Coontz, Stephanie, and Peta Henderson. Women's Work, Men's Property: The Origins of Gender and Class. Verso Books, 1986. ISBN 0805272550

- Durkheim, Émile. The Division of Labor in Society. Free Press, 1997. ISBN 0684836386

- Finley, M. I. The Ancient Economy. University of California Press, 1999. ISBN 0520219465

- Gorz, André. The Division of Labor: The Labor Process and Class Struggle in Modern Capitalism. Harvester Press, 1976. ISBN 0855271248

- Hume, David. A Treatise of Human Nature. NuVision Publications, 2007. ISBN 1595478590

- Mandeville, Bernard de. The Fable of the Bees: And Other Writings. Hackett Publishing Company, 1997. ISBN 0872203743

- Marx, Karl. Capital. Pluto Press, 2003. ISBN 074532049X.

- Montgomery, David. The Fall of the House of Labor: The Workplace, the State, and American Labor Activism, 1865-1925. Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Petty, William. The Political Anatomy of Ireland: With the Establishment for that Kingdom and Verbum sapienti. Irish University Press, 1970. ISBN 0716500930

- Plato. Republic. Hackett Publishing Company, 1992. ISBN 0872201368

- Rattansi, Ali. Marx and the Division of Labor. MacMillan, 1982. ISBN 0333285565

- Rothbard, Murray. Freedom, Inequality, Primitivism and the Division of Labor. Ludwig von Mises Institute. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- Smith, Adam. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. University of Chicago Press, 1977. ISBN 0226763749

- Steele, David Ramsay. From Marx to Mises: Post-Capitalist Society and the Challenge of Economic Calculation. Open Court, 1999. ISBN 0812690168

- Taylor, Frederick. Scientific Management. Routledge, 2003. ISBN 0415279836

- Weber, Max. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology (2 volume set). University of California Press, 1978. ISBN 978-0520035003

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.