Encyclopedia, Difference between revisions of "William Z. Ripley" - New World

m ({{Contracted}}) |

|||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

{{epname}} | {{epname}} | ||

| − | '''William Zebina Ripley''' ( | + | '''William Zebina Ripley''' (born October 13, 1867 – died August 16, 1941) was an [[United States|American]] [[economy|economist]] and [[race|racial]] theorist, famous for his tripartite racial theory of Europe and his criticisms of American corporate and railroad economics in the 1920s and 1930s. |

| − | == | + | ==Life== |

| − | |||

| − | + | '''William Z. Ripley''' was born in Medford, [[Massachusetts]], into the family of Nathaniel L. Ripley and Estimate R.E. Baldwin. He attended the [[Massachusetts Institute of Technology]] for his undergraduate education in engineering, graduating in 1890, and received a master's and doctorate degree from [[Columbia University]] in 1892 and 1893 respectively. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | In | + | In 1893, Ripley married Ida S. Davis. From 1839 until 1901, Ripley lectured on sociology at Columbia University and from 1895 until 1901 he was a professor of economics at MIT. From 1901 to the end of his career he was a professor of political economics at [[Harvard University]]. |

| − | |||

| − | Ripley's book, originally written to help finance his children's education, became a very-well respected work of early | + | Ripley was the first American recipient of the Huxley Medal of the [[Royal Anthropological Institute]] in [[1908]] on account of his contributions to anthropology. |

| + | |||

| + | As the first part of his career was mostly spent in studies in anthropology and sociology, the second part of it was totally dedicated to economy. Ripley had worked under [[Theodore Roosevelt]] on the United States Industrial Commission in 1900, helping negotiate relations between railway companies and [[anthracite coal]] companies. In 1916, he served on the Eight Hour Commission, adjusting railway wages to the new [[eight-hour workday]]. From 1917 to 1918 he served as Administrator of Labor Standards for the United States Department of War, and helped to settle railway strikes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ripley served as the Vice President of the American Economics Association in 1898, 1900, and 1901, and was elected president of it in 1933. From 1919 to 1920, he served as the chairman of the National Adjustment Commission of the United States Shipping Board, and from 1920 to 1923, he served with the [[Interstate Commerce Commission]]. In 1921, he was ICC special examiner on the construction of railroads. There, he wrote the ICC's plan for the regional consolidation of U.S. railways, which became known as the ''Ripley Plan''. In 1929, the ICC published Ripley's Plan under the title ''Complete Plan of Consolidation''. Numerous hearings were held by the ICC regarding the plan under the topic of "In the Matter of Consolidation of the Railways of the United States into a Limited Number of Systems". | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1920 Ripley started to criticize big corporations for their methods of doing business, and advocate for the corporations to make public their records of income. However, after an automobile accident in January of 1927, Ripley suffered a [[nervous breakdown]] and was forced to recuperate at a [[sanitarium]] in [[Connecticut]]. After the Wall Street Crash of 1929, he was occasionally credited with having predicted the financial disaster. One article published in 1929 implied that his automobile accident may have been part of a conspiracy. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ripley was unable to return to teaching until at least 1929. However, in the early 1930s, he continued to issue criticisms of the railroad industry labor practices. In 1931, he had also testified at a [[United States Senate|Senate]] banking inquiry, urging the curbing of investment trusts. In 1932, he appeared at the Senate Banking and Currency Committee, and demanded public inquiry into the financial affairs of corporations and authored a series of articles in the ''New York Times'' stressing the importance of railroad economics to the country's economy. Yet, by the end of the year he had suffered another nervous breakdown, and retired in early 1933. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ripley died in 1941 at his summer home in Edgecomb, [[Maine]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Work== | ||

| + | |||

| + | William Z. Ripley was a well-known sociologist and an economist, mostly remembered for his racial theory and a criticism of American corporate and railroad economics. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===''The Races of Europe''=== | ||

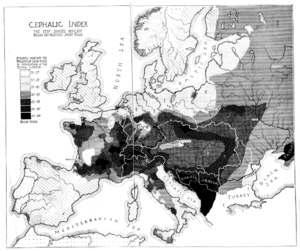

| + | [[Image:Ripley map of cephalic index in Europe.png|right|thumb|300px|Ripley's map of cephalic index in Europe, from ''[[The Races of Europe]]'' (1899).]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1899, Ripley authored a book entitled ''The Races of Europe'', which had grown out of a series of lectures he had given at the Lowell Institute at Columbia in 1896. Ripley believed that "[[race]]" was the central engine to understanding human history. However, his work also afforded strong weight to environmental and non-biological factors, such as traditions. He believed, as he wrote in the introduction to ''Races of Europe'', that: | ||

| + | |||

| + | :''"Race, properly speaking, is responsible only for those peculiarities, mental or bodily, which are transmitted with constancy along the lines of direct physical descent from father to son. Many mental traits, aptitudes, or proclivities, on the other hand, which reappear persistently in successive populations, may be derived from an entirely different source. They may have descended collaterally, along the lines of purely mental suggestion by virtue of mere social contact with preceding generations."'' (The Races of Europe, 1899). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ripley's book, originally written to help finance his children's education, became a very-well respected work of early 20th century anthropology, renowned for its careful writing, compilation, and criticism of the data of many other anthropologists in [[Europe]] and the [[United States]]. | ||

Ripley based his conclusions about race by correlating [[anthropometry|anthropometric]] data with geographical data, paying special attention to the use of the [[cephalic index]], which at the time was considered a well-established measure. However, later research determined that the cephalic index was largely an effect of the environment. From this and other socio-geographical factors, Ripley classified Europeans into three distinct races: | Ripley based his conclusions about race by correlating [[anthropometry|anthropometric]] data with geographical data, paying special attention to the use of the [[cephalic index]], which at the time was considered a well-established measure. However, later research determined that the cephalic index was largely an effect of the environment. From this and other socio-geographical factors, Ripley classified Europeans into three distinct races: | ||

| − | #'' | + | #''Teutonic race'' — members of the northern race were long-skulled (or dolichocephalic), tall in stature, and possessed pale eyes and skin. |

| − | #'' | + | #''Mediterranean race'' — members of the southern race were long-skulled (or dolichocephalic), short in stature, and possessed dark eyes and skin. |

| − | #'' | + | #''Alpine race'' — members of the central race were round-sculled (or brachycephalic), stocky in stature, and possessed intermediate eye and skin color. |

| + | |||

| + | Ripley's tripartite system of race put him at odds both with other scholars who insisted that there was only one European race, and those who insisted that there were dozens of European races (such as [[Joseph Deniker]], who Ripley saw as his chief rival). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Economics=== | ||

| + | Though he is today most often remembered for his work on race, in his time Ripley was just as famous, if not more so, for his critics of big corporations’ business strategies in 1920s and his views on [[railroad]] economics. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Starting with a series of articles in the ''Atlantic Monthly'' in 1925 under the headlines of "Stop, Look, Listen!", Ripley became a major critic of American corporate practices. In 1926, he issued a well circulated critique of [[Wall Street]]'s practices of [[speculation]] and [[secrecy]]. More than often corporations would conceal their affairs from the ordinary stockholders. Ripley received a full-page profile in the ''New York Times'' magazine, with the headline, "When Ripley Speaks, Wall Street Heeds”. He advocated for corporations make public their reports of their income and regularly report on the state of their inventories. Since corporations were reluctant to do that, Ripley asked the Federal Trade Commission demand such reports. | ||

| + | |||

| + | After the economic crash in 1929, Ripley was often credited for predicting the crash. He later advocated for the federal government having bigger role in economy. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ripley was also a strong critic of a railroad economics of United States. He believed that railroads are of a particular importance for the economy of the country, and he advocated for the greater discipline within the railroad industry. He proposed the reorganization of the complete railroad system. Such for example, under his Ripley plan, he suggested that administrative functions of the Interstate Commerce Commission (locomotive inspection, accident investigation, safety equipment orders) be transferred to the Department of Transportation. | ||

| − | + | ==Legacy== | |

| − | ''The Races of Europe'' | + | ''The Races of Europe'' was an influential book of the [[Progressive Era]] in the field of racial taxonomy. Ripley's tripartite system was especially championed by [[Madison Grant]], who changed Ripley's "Teutonic" type into Grant's own [[Nordic race|Nordic type]] (taking the name, but little else, from Deniker), which he postulated as a [[master race]]. It is in this light that Ripley's work on race is usually remembered today, though little of Grant's supremacist ideology is present in Ripley's original work. |

| − | + | Ripley’s work in economy, especially his criticism of the old railway system, helped reconstruct and modernize American railroad system. | |

| + | ==Publications== | ||

| − | + | * Ripley, William Z. 1899. ''A selected bibliography of the anthropology and ethnology of Europe''. D. Appleton | |

| − | Ripley | + | * Ripley, William Z. 1899. ''Notes on map making and graphic representation''. American Statistical Association |

| − | + | * Ripley, William Z. 1908. ''The European population of the United States: The Huxley memorial lecture for 1908''. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. | |

| − | + | * Ripley, William Z. 1914. ''Railroad over-capitalization''. Harvard University Press. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | * Ripley, William Z. 1916. ''Trusts, pools and corporations''. | |

| − | Ripley | + | * Ripley, William Z. 1973 (original work published in 1929). ''Main Street and Wall Street''. Arno Press. ISBN 0405051093 |

| − | |||

| − | + | * Ripley, William Z. 1978. ''Financial History of Virginia 1609-1776''. AMS Press Inc. ISBN 0404510108 | |

| + | |||

| + | * Ripley, William Z. 1999 (original work published in 1899). ''The Races of Europe: A Sociological Study''. Johnson Reprint Corp. ISBN 0384509304 | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Ripley, William Z. 2000. ''Railway Problems'', (2 vols.). Beard Books. ISBN 1587980754 | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Ripley, William Z. 2005 (original work published in 1913). ''Railroads: Rates and Regulation. Adamant Media Corporation''. ISBN 1421221977 | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | |||

| + | * Guterl, Matthew P. 2001. ''The Color of Race in America, 1900-1940.'' Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Leonard, Thomas C. 2003. More Merciful and Not Less Effective: Eugenics and Economics in the Progressive Era. ''Historical of Political Economy'' 35(4), 687-712. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Leonard, Thomas C. 2005. [http://www.princeton.edu/~tleonard/papers/retrospectives.pdf Eugenics and Economics in the Progressive Era. ''Journal of Economic Perspectives'', 19( 4), 207–224 | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Thomas, William G. 1999. ''Lawyering for the Railroad: Business, Law, and Power in the New South.'' Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0807125040 | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Watt, William J. 2000. ''The Pennsylvania Railroad in Indiana: Railroads Past and Present''. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253337089 | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==External links== | ||

| + | |||

| + | * [http://web.jjay.cuny.edu/~thematic/umbach/lostworlds/1908.html ''Races in United States''] – Full text, originally from ''The Atlantic Monthly'', December 1908; Volume 102, No. 6; pages 745-759 | ||

| + | |||

| + | * [http://hbswk.hbs.edu/archive/2951.html ''State Regulators and Pragmatic Federalism in the United States, 1889-1945''] – Text by William Childs from Ohio State University on the history of railroad laws | ||

{{Credit1|William_Z._Ripley|86609024|}} | {{Credit1|William_Z._Ripley|86609024|}} | ||

Revision as of 14:36, 16 November 2006

William Zebina Ripley (born October 13, 1867 – died August 16, 1941) was an American economist and racial theorist, famous for his tripartite racial theory of Europe and his criticisms of American corporate and railroad economics in the 1920s and 1930s.

Life

William Z. Ripley was born in Medford, Massachusetts, into the family of Nathaniel L. Ripley and Estimate R.E. Baldwin. He attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for his undergraduate education in engineering, graduating in 1890, and received a master's and doctorate degree from Columbia University in 1892 and 1893 respectively.

In 1893, Ripley married Ida S. Davis. From 1839 until 1901, Ripley lectured on sociology at Columbia University and from 1895 until 1901 he was a professor of economics at MIT. From 1901 to the end of his career he was a professor of political economics at Harvard University.

Ripley was the first American recipient of the Huxley Medal of the Royal Anthropological Institute in 1908 on account of his contributions to anthropology.

As the first part of his career was mostly spent in studies in anthropology and sociology, the second part of it was totally dedicated to economy. Ripley had worked under Theodore Roosevelt on the United States Industrial Commission in 1900, helping negotiate relations between railway companies and anthracite coal companies. In 1916, he served on the Eight Hour Commission, adjusting railway wages to the new eight-hour workday. From 1917 to 1918 he served as Administrator of Labor Standards for the United States Department of War, and helped to settle railway strikes.

Ripley served as the Vice President of the American Economics Association in 1898, 1900, and 1901, and was elected president of it in 1933. From 1919 to 1920, he served as the chairman of the National Adjustment Commission of the United States Shipping Board, and from 1920 to 1923, he served with the Interstate Commerce Commission. In 1921, he was ICC special examiner on the construction of railroads. There, he wrote the ICC's plan for the regional consolidation of U.S. railways, which became known as the Ripley Plan. In 1929, the ICC published Ripley's Plan under the title Complete Plan of Consolidation. Numerous hearings were held by the ICC regarding the plan under the topic of "In the Matter of Consolidation of the Railways of the United States into a Limited Number of Systems".

In 1920 Ripley started to criticize big corporations for their methods of doing business, and advocate for the corporations to make public their records of income. However, after an automobile accident in January of 1927, Ripley suffered a nervous breakdown and was forced to recuperate at a sanitarium in Connecticut. After the Wall Street Crash of 1929, he was occasionally credited with having predicted the financial disaster. One article published in 1929 implied that his automobile accident may have been part of a conspiracy.

Ripley was unable to return to teaching until at least 1929. However, in the early 1930s, he continued to issue criticisms of the railroad industry labor practices. In 1931, he had also testified at a Senate banking inquiry, urging the curbing of investment trusts. In 1932, he appeared at the Senate Banking and Currency Committee, and demanded public inquiry into the financial affairs of corporations and authored a series of articles in the New York Times stressing the importance of railroad economics to the country's economy. Yet, by the end of the year he had suffered another nervous breakdown, and retired in early 1933.

Ripley died in 1941 at his summer home in Edgecomb, Maine.

Work

William Z. Ripley was a well-known sociologist and an economist, mostly remembered for his racial theory and a criticism of American corporate and railroad economics.

The Races of Europe

In 1899, Ripley authored a book entitled The Races of Europe, which had grown out of a series of lectures he had given at the Lowell Institute at Columbia in 1896. Ripley believed that "race" was the central engine to understanding human history. However, his work also afforded strong weight to environmental and non-biological factors, such as traditions. He believed, as he wrote in the introduction to Races of Europe, that:

- "Race, properly speaking, is responsible only for those peculiarities, mental or bodily, which are transmitted with constancy along the lines of direct physical descent from father to son. Many mental traits, aptitudes, or proclivities, on the other hand, which reappear persistently in successive populations, may be derived from an entirely different source. They may have descended collaterally, along the lines of purely mental suggestion by virtue of mere social contact with preceding generations." (The Races of Europe, 1899).

Ripley's book, originally written to help finance his children's education, became a very-well respected work of early 20th century anthropology, renowned for its careful writing, compilation, and criticism of the data of many other anthropologists in Europe and the United States.

Ripley based his conclusions about race by correlating anthropometric data with geographical data, paying special attention to the use of the cephalic index, which at the time was considered a well-established measure. However, later research determined that the cephalic index was largely an effect of the environment. From this and other socio-geographical factors, Ripley classified Europeans into three distinct races:

- Teutonic race — members of the northern race were long-skulled (or dolichocephalic), tall in stature, and possessed pale eyes and skin.

- Mediterranean race — members of the southern race were long-skulled (or dolichocephalic), short in stature, and possessed dark eyes and skin.

- Alpine race — members of the central race were round-sculled (or brachycephalic), stocky in stature, and possessed intermediate eye and skin color.

Ripley's tripartite system of race put him at odds both with other scholars who insisted that there was only one European race, and those who insisted that there were dozens of European races (such as Joseph Deniker, who Ripley saw as his chief rival).

Economics

Though he is today most often remembered for his work on race, in his time Ripley was just as famous, if not more so, for his critics of big corporations’ business strategies in 1920s and his views on railroad economics.

Starting with a series of articles in the Atlantic Monthly in 1925 under the headlines of "Stop, Look, Listen!", Ripley became a major critic of American corporate practices. In 1926, he issued a well circulated critique of Wall Street's practices of speculation and secrecy. More than often corporations would conceal their affairs from the ordinary stockholders. Ripley received a full-page profile in the New York Times magazine, with the headline, "When Ripley Speaks, Wall Street Heeds”. He advocated for corporations make public their reports of their income and regularly report on the state of their inventories. Since corporations were reluctant to do that, Ripley asked the Federal Trade Commission demand such reports.

After the economic crash in 1929, Ripley was often credited for predicting the crash. He later advocated for the federal government having bigger role in economy.

Ripley was also a strong critic of a railroad economics of United States. He believed that railroads are of a particular importance for the economy of the country, and he advocated for the greater discipline within the railroad industry. He proposed the reorganization of the complete railroad system. Such for example, under his Ripley plan, he suggested that administrative functions of the Interstate Commerce Commission (locomotive inspection, accident investigation, safety equipment orders) be transferred to the Department of Transportation.

Legacy

The Races of Europe was an influential book of the Progressive Era in the field of racial taxonomy. Ripley's tripartite system was especially championed by Madison Grant, who changed Ripley's "Teutonic" type into Grant's own Nordic type (taking the name, but little else, from Deniker), which he postulated as a master race. It is in this light that Ripley's work on race is usually remembered today, though little of Grant's supremacist ideology is present in Ripley's original work.

Ripley’s work in economy, especially his criticism of the old railway system, helped reconstruct and modernize American railroad system.

Publications

- Ripley, William Z. 1899. A selected bibliography of the anthropology and ethnology of Europe. D. Appleton

- Ripley, William Z. 1899. Notes on map making and graphic representation. American Statistical Association

- Ripley, William Z. 1908. The European population of the United States: The Huxley memorial lecture for 1908. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland.

- Ripley, William Z. 1914. Railroad over-capitalization. Harvard University Press.

- Ripley, William Z. 1916. Trusts, pools and corporations.

- Ripley, William Z. 1973 (original work published in 1929). Main Street and Wall Street. Arno Press. ISBN 0405051093

- Ripley, William Z. 1978. Financial History of Virginia 1609-1776. AMS Press Inc. ISBN 0404510108

- Ripley, William Z. 1999 (original work published in 1899). The Races of Europe: A Sociological Study. Johnson Reprint Corp. ISBN 0384509304

- Ripley, William Z. 2000. Railway Problems, (2 vols.). Beard Books. ISBN 1587980754

- Ripley, William Z. 2005 (original work published in 1913). Railroads: Rates and Regulation. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1421221977

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Guterl, Matthew P. 2001. The Color of Race in America, 1900-1940. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Leonard, Thomas C. 2003. More Merciful and Not Less Effective: Eugenics and Economics in the Progressive Era. Historical of Political Economy 35(4), 687-712.

- Leonard, Thomas C. 2005. [http://www.princeton.edu/~tleonard/papers/retrospectives.pdf Eugenics and Economics in the Progressive Era. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19( 4), 207–224

- Thomas, William G. 1999. Lawyering for the Railroad: Business, Law, and Power in the New South. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0807125040

- Watt, William J. 2000. The Pennsylvania Railroad in Indiana: Railroads Past and Present. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253337089

External links

- Races in United States – Full text, originally from The Atlantic Monthly, December 1908; Volume 102, No. 6; pages 745-759

- State Regulators and Pragmatic Federalism in the United States, 1889-1945 – Text by William Childs from Ohio State University on the history of railroad laws

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.