Difference between revisions of "Utopia" - New World Encyclopedia

m ({{Contracted}}) |

MaedaMartha (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{otheruses}} | {{otheruses}} | ||

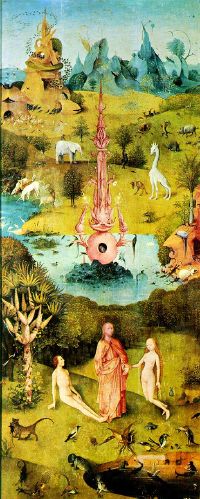

| − | [[Image:Hieronymus Bosch - The Garden of Earthly Delights - The Earthly Paradise (Garden of Eden).jpg|thumbnail|right|200px|Left panel (''The Earthly Paradise'', Garden of Eden), from [[Hieronymus_Bosch|Hieronymus Bosch]]'s '' | + | [[Image:Hieronymus Bosch - The Garden of Earthly Delights - The Earthly Paradise (Garden of Eden).jpg|thumbnail|right|200px|Left panel (''The Earthly Paradise'', Garden of Eden), from [[Hieronymus_Bosch|Hieronymus Bosch]]'s ''The Garden of Earthly Delights''. This artist showed in his paintings part of the desires that induce human beings in pursuit of a heaven on earth.]] |

| − | '''Utopia''', | + | '''Utopia''' is a term denoting a visionary or ideally perfect state of society, whose members live the best possible life. The term “Utopia” was coined by Thomas More from the Greek words ou (no or not), and topos (place), as the name for the ideal state in his book, "De optimo reipublicae statu deque nova insula Utopia" (Louvain, 1516). |

| − | + | “Utopianism” refers to the various ways in which people think about, depict and attempt to create a perfect society. Utopian thought deals with morality, ethics, psychology and political philosophy, and originates from the belief that reason and intelligence can bring about the betterment of society. It is usually characterized by optimism that an ideal society is possible. Utopianism plays an important role in motivating social and political change. | |

| − | " | + | The adjective "utopian" is sometimes used in a negative connotation to discredit ideas as too advanced, too optimistic or unrealistic and impossible to realize. An example is [[Marxism|Marxist]] use of such expressions as "utopian socialism.” |

| − | + | “Utopian”also been used to describe actual communities founded in attempts to create an ideal economic and political system. Many works of utopian literature offer detailed and practical descriptions of an ideal society. | |

| + | ==More's ''Utopia''== | ||

| + | [[Image:Utopia.jpg|right|thumb|Woodcut by [[Ambrosius Holbein]] for the 1518 edition of Thomas More's ''Utopia'']] | ||

| − | + | The term “Utopia” was coined by Thomas More from the Greek words ou (no or not), and topos (place), as the name for the ideal state in his book, "De optimo reipublicae statu deque nova insula Utopia" (“Utopia” Louvain, 1516). The book is narrated by a Portuguese traveler named Raphael Hythlodaeus, who criticizes the laws and customs of European states while admiring the ideal institutions which he observes during a five year sojourn on the island of Utopia. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Utopia, largely based on [[Plato]]'s ''Republic,'' is a perfect society, where poverty and misery have been eliminated, there are few laws and no lawyers, and the citizens, though ready to defend themselves if necessary, are pacifists. Citizens hold property in common, and care is taken to teach everyone a trade from which he can make a living, so that there is no need for crime. Agriculture is treated as a science and taught to children as part of their school curriculum; every citizen spends some of his life working on a farm. The people live in fifty-four cities, separated from each other by a distance of at least twenty-four miles. The rural population lives in communal farmhouses scattered through the countryside. Everyone works only six hours a day; this is sufficient because the people are industrious and do not require the production of useless luxuries for their consumption. A body of wise and educated representatives deliberates on public affairs, and the country is governed by a prince, selected from among candidates chosen by the people. The prince is elected for life, but can be removed from office for tyranny. All religions are tolerated and exist in harmony; atheism is not permitted since, if a man does not fear a god of some kind, he will commit evil acts and weaken society. Utopia rarely sends its citizens to war, but hires [[mercenary|mercenaries]] from among its warlike neighbors, deliberately sending them into danger in the hope that the more belligerent populations of all surrounding countries will be gradually eliminated. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | “Utopia” was first published in Louvain in 1516, without More’s knowledge, by his friend Erasmus. It was not until 1551, sixteen years after More's execution as a traitor, that it was first published in England as an [[English language|English]] translation. The word “Utopia” overtook More's short work and has been used ever since to describe any type of imaginary ideal society. | |

| − | + | Although some readers have regarded Utopia as a realistic blueprint for a working nation, More probably intended it as a satire, allowing him to call attention to European political and social abuses without risking censure by the king. The similarities to the ideas later developed by Marx are evident, but More was a devout Roman Catholic and probably used monastic communalism as his model. The politics of ''Utopia'' have been seen as influential to the ideas of [[Anabaptism]], [[Mormonism]] and [[Communism]]. An applied example of More's utopia can be seen in [[Vasco de Quiroga]]'s implemented society in Michoacán, [[México]], which was directly taken and adapted from More's work. | |

| + | == Utopian Literature == | ||

| + | The word “Utopia” overtook More's short work and has been used ever since to describe any type of imaginary ideal society. Although he may not have founded the genre of Utopian and dystopian fiction, More certainly popularized it. Some of the early works which owe something to ''Utopia'' include ''The City of the Sun'' by Tommaso Campanella, ''Description of the Republic of Christianopolis'' by Johannes Valentinus Andreae, New Atlantis by [[Francis Bacon]] and Candide by [[Voltaire]]. | ||

| − | + | The more modern genre of science fiction frequently depicts utopian or dystopian societies, in fictional works such as [[Aldous Huxley]]'s ''Brave New World'' (1932) ''Lost Horizon'' by [[James Hilton]] (1933), "A Modern Utopia" (1905) and "New Worlds for Old" (1908) by H. G. Wells, ”The Great Explosion”, [[Eric Frank Russell]] (1963) “Andromeda Nebula''(1957) by [[Ivan Efremov]], “1984” (1949) by George Orwell, and The Giver (1993) by Lois Lowry. Authors of utopian fiction are able to explore some of the problems raised by utopian concepts and to develop interesting consequences. Many works make use of an outsider, a time-traveler or a foreigner, who observes the features of the society and describes them to the reader. | |

| − | + | == Utopianism == | |

| − | [[ | + | Utopian thought is born from the premise that through reason and intelligence, man is capable of creating an ideal society in which every individual can achieve fulfillment without infringing on the happiness and well-being of the other members of society. It includes the consideration of morality, ethics, psychology and social and political philosophy. Utopian thinking is generally confined to physical life on earth, although it may include the preparation of the members of society for a perceived afterlife. It invariably includes criticism of the current state of society and seeks ways to correct or eliminate abuses. Utopianism is characterized by tension between philosophical ideals and the practical realities of society, such as crime and immorality; there is also a conflict between respect for individual freedom and the need to maintain order. Utopian thinking implies a creative process that challenges existing concepts, rather than an ideology or justification for a belief system which is already in place. |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | Two of Plato’s dialogues, “Republic, and “Laws” contain one of the earliest attempts to define a political organization that will not only allow its citizens to live in harmony, but will provide the education and experience necessary for each citizen to realize his highest potential. | |

| − | + | During the nineteenth century, Henri Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, and Etienne Cabet in France, and Robert Owen in England, known as the utopian socialists, popularized the idea of creating small, experimental communities to put philosophical ideals into practice. Marx and Engels, while recognizing that utopianism offered a vision for a better future, dismissed it as lacking a wider understanding of social and political realities which could contribute to actual political change. Bloch and Marcuse made a distinction between “abstract” utopias based on fantasy and dreams, and “concrete” utopias based on critical social theory. Utopianism is considered to originate in the imaginative capacity of the subconscious mind, which is able to transcend conscious reality by projecting images of hopes, dreams and desires. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Utopian ideas, though they may never be fully realized, play an important role in bringing about positive social change. They allow thinkers to distance themselves from the existing reality and consider new possibilities. The optimism that a better society can be achieved provides motivation and a focal point for those involved in bringing about social or political change. Women’s rights and feminism, the Civil Rights movement, the establishment of a welfare system to take care of the poor, the Red Cross, and multiculturalism are all examples of utopian thinking applied to practical life. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Types of Utopia == | |

| − | + | ===Economic Utopias === | |

| − | The | + | The harsh economic conditions of the nineteenth century and the social disruption created by the development of commercialism and [[capitalism]] gave rise to a “utopian socialist" movement. It was characterized by shared ideals: an equal distribution of goods according to need, frequently with the total abolition of [[money]]; and citizens laboring for the common good, doing work which they enjoyed, and having ample leisure for the cultivation of the arts and sciences. One such utopia was described in [[Edward Bellamy]]'s ''Looking Backward''. Another socialist utopia was [[William Morris]]' ''News from Nowhere'', written partially in criticism of the bureaucratic nature of Bellamy's utopia. As the socialist movement developed it moved away from utopianism; [[Marx]] in particular became a harsh critic of earlier socialisms which he described as “utopian”, saying they were incapable of bringing about substantial political change. |

| − | + | [[Capitalism|Capitalist]] utopias, such as the one portrayed in [[Robert A. Heinlein]]'s ''[[The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress]]'' or Ayn Rand’s “The Fountainhead,” are generally [[individualism|individualistic]] and [[Libertarianism|libertarian]], are based on [[free market|perfect market]] economies, in which there is no [[market failure]]. [[Eric Frank Russell]]'s book ''The Great Explosion'' (1963) details an economic and social utopia, the first to mention of the idea of [[Local Exchange Trading Systems]] (LETS). | |

| − | + | === Political and Historical Utopias === | |

| + | Political utopias are ones in which the government establishes a society that is striving toward perfection. These utopias are based on laws administered by a government, and often restrict individualism when it conflicts with the primary goals of the society. Sometimes the state or government replaces religious and family values. A global utopia of [[world peace]] is often seen as one of the possible inevitable ends of history. | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | ===Religious Utopia=== | ||

| + | [[Image:New Harmony by F. Bate (View of a Community, as proposed by Robert Owen) printed 1838.jpg|300px|right|thumb|New Harmony, Indiana, a utopian attempt; depicted as proposed by [[Robert Owen]]]] | ||

| − | + | Through history a number of religious communities have been created to reflect the virtues and values they believe have been lost or which await them in the [[Afterlife]]. | |

| − | + | In the [[United States]] and [[Europe]] during and after the [[Second Great Awakening]] of the nineteenth century, many radical religious groups sought to form communities where all aspects of people's lives could be governed by their faith. Among the best-known of these utopian societies wer the Puritans, and the [[Shakers|Shaker]] movement, which originated in England in the 18th century but moved to America shortly after its founding. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The most common utopias are based on [[religion|religious]] ideals, and usually required adherence to a particular religious tradition. The [[Judaism|Jewish]], [[Christianity|Christian]] and [[Islam|Islamic]] concepts of the [[Garden of Eden]] and [[Heaven]] may be interpreted as forms of [[utopianism]], especially in their[[folk religion|folk-religious]] forms. Such religious "utopias" are often described as "gardens of delight", implying an existence free from worry in a state of bliss or enlightenment. They postulate existences free from sin, pain, poverty and death, and often assume communion with beings such as [[angel]]s or the [[houri]]. In a similar sense the [[Hinduism|Hindu]] concept of [[Moksha]] and the [[Buddhism|Buddhist]] concept of [[Nirvana]] may be thought of as a kind of utopia. | |

| − | + | Many cultures and cosmogonies include a myth or memory of a distant past when humankind lived in a primitive and simple state of perfect happiness and fulfillment. The various myths describe a time when there was an instinctive harmony between man and nature, and man’s needs were easily supplied by the abundance of nature. There was no motive for [[war]] or oppression, or any need for hard and painful work. Humans were simple and [[piety|pious]], and felt themselves close to the gods. These mythical or religious archetypes resurge with special vitality during difficult times, when the myth is not projected towards the remote past, but towards the future or a distant and fictional place (for example, [[Cockaygne|The Land of Cockaygne]], a straightforward parody of a paradise), where the possibility of living happily must exist. | |

'''Golden Age''' | '''Golden Age''' | ||

[[Image:Goldenes-Zeitalter-1530-2.jpg|thumbnail|right|200px|''The Golden Age'' by Lucas Cranach the Elder.]] | [[Image:Goldenes-Zeitalter-1530-2.jpg|thumbnail|right|200px|''The Golden Age'' by Lucas Cranach the Elder.]] | ||

| − | + | ''Works and Days,' compilation of the mythological tradition by the [[Greek language|Greek]] [[poet]] [[Hesiod]], around the eighth century b.c.e., explained that, prior to the present era, there were four progressively most perfect ones. | |

| − | + | A medieval poem (c. 1315) , entitled "The Land of Cokaygne" depicts a land of extravagance and excess where cooked larks flew straight into one's mouth; the rivers ran with wine, and a fountain of youth kept everyone young and active. | |

:Far in the sea, to the west of Spain, | :Far in the sea, to the west of Spain, | ||

| Line 79: | Line 70: | ||

:Cokaygne is of far fairer sight.... | :Cokaygne is of far fairer sight.... | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | === Scientific and Technological Utopias === | |

| − | + | Scientific and technical utopias are set in the future, when it is believed that advanced [[science]] and [[technology]] will allow utopian living standards; for example, the absence of [[death]] and suffering; changes in [[human nature]] and the human condition. These utopian societies tend to change what "human" is all about. Normal human functions, such as sleeping, eating and even reproduction are replaced by artificial means. | |

| − | + | ===Related terms=== | |

| − | + | *'''Dystopia''' is a ''negative'' utopia: a world wherein utopian ideals have been subverted. example: [[George Orwell]]'s ''1984'', [[Aldous Huxley]]'s ''Brave New World''. | |

| − | + | *'''Eutopia''' is a ''positive'' utopia, roughly equivalent to the regular use of the word "utopia". | |

| − | + | *'''Outopia''' is argued to be the word "Utopia" was derived from, coming from the latin 'Uo-' for "no" and '-topos' for "place" bringing a meaning of "no place" a fictional, non-realistic place | |

| − | + | *'''Heterotopia''', the "other place", with its real and imagined possibilities (a mix of "utopian" [[escapism]] and turning virtual possibilities into reality) — example: [[cyberspace]]. [[Samuel R. Delany]]'s novel ''Trouble on Triton'' is subtitled ''An Ambiguous Heterotopia'' to highlight that it is not strictly utopian (though certainly not dystopian). The novel offers several conflicting perspectives on the concept of utopia. | |

| − | + | *'''Ourtopia''' combines the English 'our' with the Greek 'topos' to give 'our place'—the nearest thing to a utopian planet that is actually attainable. | |

| − | + | Other subcategories, developed by Ruth Levitas, include Arcadias and Cockaygnes. | |

==Examples of utopia== | ==Examples of utopia== | ||

| − | *'' | + | *''New Australia'' A utopian movement founded in 1893 in Paraguay by William Lane |

| − | *'' | + | *'' Plato's Republic '' (400 B.C.E.) was, at least on one level, a description of a political utopia ruled by an elite of philosopher king s, conceived by Plato . (Compare to his Laws (dialogue)|Laws , discussing laws for a real city.) [http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/150 a Gutenburg text of the book] |

| − | *'' | + | *'' The City of God '' (written 413 – 426 ) by Augustine of Hippo , describes an ideal city, the”eternal”Jerusalem, the archetype of all”Christian”utopias. |

| − | *'' | + | *'' Utopia (Novel)|Utopia '' ( 1516 ) by Thomas More [http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/2130 a Gutenberg text of the book] |

| − | *'' | + | *'' Christianopolis|Reipublicae Christianopolitanae descriptio (Beschreibung des Staates Christenstadt) '' ( 1619 ) by Johann Valentin Andrea|Johann Valentin Andreæ , describes a Christian religious utopia inhabited by a community of scholar-artisans and run as a democracy. |

| − | *'' | + | *'' The Anatomy of Melancholy '' ( 1621 ) by Robert Burton (scholar)|Robert Burton , a utopian society is described in the preface. |

| − | *'' | + | *'' The City of the Sun '' ( 1623 ) by Tommaso Campanella depicts a theocratic and communist society. |

| − | *'' | + | *'' The New Atlantis '' ( 1627 ) by Francis Bacon (philosopher)|Francis Bacon |

| − | *'' | + | *'' Oceana '' ( 1656 the Integral, praising the efficiency, the rationality, and the happiness that life within the confines of the One State can bring to those worlds the Integral will someday visit. |

| − | * | + | * Aldous Huxley 's '' Brave New World '' ( 1932 ) can be considered an example of pseudo-utopian satire (see also dystopia ). One of his other books, '' Island (novel)|Island '' ( 1962 ), demonstrates a positive utopia. |

| − | *'' | + | *'' Shangri-La '' described in the novel '' Lost Horizon '' by James Hilton ( 1933 ) |

| − | *'' | + | *'' Islandia '' ( 1942 ), by Austin Tappan Wright , an imaginary island in the Southern Hemisphere, a utopian containing many Arcadia (utopia)|Arcadian elements, including a rejection of technology. |

| − | * | + | * B. F. Skinner 's '' Walden Two '' ( 1948 ) |

| − | *'' | + | *'' The Cloud of Magellan '' ( 1955 ) by Stanisław Lem |

| − | *'' | + | *'' Andromeda Nebula '' ( 1957 ) is a classic communist utopia by Ivan Efremov |

| − | * | + | * The Great Explosion , Eric Frank Russell 1963 In the last section setting out a workable utopian economic system leading to a different social and political reality. |

| − | *'' | + | *'' The Corridors of Time '' by Poul Anderson (1965) |

| − | *'' | + | *'' Star Trek '' ( 1966 ) science fiction television series by Gene Roddenberry |

| − | *'' | + | *'' The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas '' ( 1969 ), by Ursula K. Le Guin |

| − | + | *''The Kingdom of Zeal in Chrono Trigger '' ( 1995 ) is a utopian society. | |

| − | *''The | + | *''|The Hedonistic Imperative '' ( 1996 ), an online manifesto by David Pearce , outlines how genetic engineering and nanotechnology will abolish suffering in all sentient life. |

| − | *'' | + | *''The Kin of Ata Are Waiting for You'' ( 1997 ) by Dorothy Bryant |

| − | *''The Kin of Ata Are Waiting for You'' ( | + | *'' The Matrix '' ( 1999 ), a film by the Wachowski brothers , describes a virtual reality controlled by artificial intelligence such as Agent Smith . Smith says that the first Matrix was a utopia, but humans rejected it because they "define their reality through misery and suffering." Therefore, the Matrix was redesigned to simulate human civilization with all its suffering. |

| − | *'' | + | *''Equilibrium '' ( 2002 ), a film describing a future in which feelings are forbidden. *”Fahrenheit 451” by Ray Bradbury . |

| − | *'' | + | *'' Xen: Ancient English Edition '', ( 2004 ) "translated" by D.J. Solomon |

| − | *'' | + | *'' Ensaio sobre a Lucidez '' ("Treatise on Lucidity") by José Saramago ( 2004 ), describes a city where there is 83% of blank votes at an election. |

| − | *'' | + | *'' Globus Cassus, '' ( 2004 ), is a project for the transformation of the Earth into a large, hollow structure inhabited on the inside |

| − | + | *The first story arc in the seventh season ( 2004 - 2005 ) of the supernatural dramedy series Charmed involves the transformation of the world into utopia through the fear of a common enemy. | |

| − | *'' | ||

| − | *The first story arc in the seventh season ( | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * | + | *Kateb, G. “Utopianism and Its Enemies” New York, Free Press, 1963. |

| − | * | + | *Kumar, Krishan (1991) ''Utopianism'' .Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-335-15361-5 |

| − | * | + | *Kumar, K (1987) ''Utopia and Anti-utopia in Modern Times'' Oxford: Blackwell. 1979. ISBN 0-631-16714-5 |

| + | *Levitas, Ruth. Concept of Utopia (Utopianism & Communitarianism) .Syracuse University Press; 1st ed. edition, 1991. | ||

| + | *Mannheim, Karl. Ideology and Utopia: An Introduction to the SOCIOLOGY (740) of Knowledge. Harvest Books; Reprint edition, 1955. | ||

| + | *Manuel, Frank & |Manuel, Fritzie ''Utopian Thought in the Western World'' . Oxford: Blackwell, 1979. ISBN 0-674-93185-8 | ||

| − | ==Links | + | == External Links == |

* Full text of [http://www.gutenberg.net/etext/2130 Thomas More's Utopia] from [[Project Gutenberg]] | * Full text of [http://www.gutenberg.net/etext/2130 Thomas More's Utopia] from [[Project Gutenberg]] | ||

* [http://www.bartleby.com/65/ut/Utopia.html Utopia - The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2001] | * [http://www.bartleby.com/65/ut/Utopia.html Utopia - The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2001] | ||

* [http://www.utoronto.ca/utopia/ Society for Utopian Studies] is the Main Page for the Society for Utopian Studies, an international, interdisciplinary association devoted to the study of utopianism in all its forms, with a particular emphasis on literary and experimental utopias. | * [http://www.utoronto.ca/utopia/ Society for Utopian Studies] is the Main Page for the Society for Utopian Studies, an international, interdisciplinary association devoted to the study of utopianism in all its forms, with a particular emphasis on literary and experimental utopias. | ||

* [http://www.abolitionist-soci | * [http://www.abolitionist-soci | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{credit|88884514}} | {{credit|88884514}} | ||

Revision as of 16:25, 13 December 2006

- For other uses, see Utopia (disambiguation).

Utopia is a term denoting a visionary or ideally perfect state of society, whose members live the best possible life. The term “Utopia” was coined by Thomas More from the Greek words ou (no or not), and topos (place), as the name for the ideal state in his book, "De optimo reipublicae statu deque nova insula Utopia" (Louvain, 1516).

“Utopianism” refers to the various ways in which people think about, depict and attempt to create a perfect society. Utopian thought deals with morality, ethics, psychology and political philosophy, and originates from the belief that reason and intelligence can bring about the betterment of society. It is usually characterized by optimism that an ideal society is possible. Utopianism plays an important role in motivating social and political change.

The adjective "utopian" is sometimes used in a negative connotation to discredit ideas as too advanced, too optimistic or unrealistic and impossible to realize. An example is Marxist use of such expressions as "utopian socialism.”

“Utopian”also been used to describe actual communities founded in attempts to create an ideal economic and political system. Many works of utopian literature offer detailed and practical descriptions of an ideal society.

More's Utopia

The term “Utopia” was coined by Thomas More from the Greek words ou (no or not), and topos (place), as the name for the ideal state in his book, "De optimo reipublicae statu deque nova insula Utopia" (“Utopia” Louvain, 1516). The book is narrated by a Portuguese traveler named Raphael Hythlodaeus, who criticizes the laws and customs of European states while admiring the ideal institutions which he observes during a five year sojourn on the island of Utopia.

Utopia, largely based on Plato's Republic, is a perfect society, where poverty and misery have been eliminated, there are few laws and no lawyers, and the citizens, though ready to defend themselves if necessary, are pacifists. Citizens hold property in common, and care is taken to teach everyone a trade from which he can make a living, so that there is no need for crime. Agriculture is treated as a science and taught to children as part of their school curriculum; every citizen spends some of his life working on a farm. The people live in fifty-four cities, separated from each other by a distance of at least twenty-four miles. The rural population lives in communal farmhouses scattered through the countryside. Everyone works only six hours a day; this is sufficient because the people are industrious and do not require the production of useless luxuries for their consumption. A body of wise and educated representatives deliberates on public affairs, and the country is governed by a prince, selected from among candidates chosen by the people. The prince is elected for life, but can be removed from office for tyranny. All religions are tolerated and exist in harmony; atheism is not permitted since, if a man does not fear a god of some kind, he will commit evil acts and weaken society. Utopia rarely sends its citizens to war, but hires mercenaries from among its warlike neighbors, deliberately sending them into danger in the hope that the more belligerent populations of all surrounding countries will be gradually eliminated.

“Utopia” was first published in Louvain in 1516, without More’s knowledge, by his friend Erasmus. It was not until 1551, sixteen years after More's execution as a traitor, that it was first published in England as an English translation. The word “Utopia” overtook More's short work and has been used ever since to describe any type of imaginary ideal society.

Although some readers have regarded Utopia as a realistic blueprint for a working nation, More probably intended it as a satire, allowing him to call attention to European political and social abuses without risking censure by the king. The similarities to the ideas later developed by Marx are evident, but More was a devout Roman Catholic and probably used monastic communalism as his model. The politics of Utopia have been seen as influential to the ideas of Anabaptism, Mormonism and Communism. An applied example of More's utopia can be seen in Vasco de Quiroga's implemented society in Michoacán, México, which was directly taken and adapted from More's work.

== Utopian Literature ==

The word “Utopia” overtook More's short work and has been used ever since to describe any type of imaginary ideal society. Although he may not have founded the genre of Utopian and dystopian fiction, More certainly popularized it. Some of the early works which owe something to Utopia include The City of the Sun by Tommaso Campanella, Description of the Republic of Christianopolis by Johannes Valentinus Andreae, New Atlantis by Francis Bacon and Candide by Voltaire.

The more modern genre of science fiction frequently depicts utopian or dystopian societies, in fictional works such as Aldous Huxley's Brave New World (1932) Lost Horizon by James Hilton (1933), "A Modern Utopia" (1905) and "New Worlds for Old" (1908) by H. G. Wells, ”The Great Explosion”, Eric Frank Russell (1963) “Andromeda Nebula(1957) by Ivan Efremov, “1984” (1949) by George Orwell, and The Giver (1993) by Lois Lowry. Authors of utopian fiction are able to explore some of the problems raised by utopian concepts and to develop interesting consequences. Many works make use of an outsider, a time-traveler or a foreigner, who observes the features of the society and describes them to the reader.

Utopianism

Utopian thought is born from the premise that through reason and intelligence, man is capable of creating an ideal society in which every individual can achieve fulfillment without infringing on the happiness and well-being of the other members of society. It includes the consideration of morality, ethics, psychology and social and political philosophy. Utopian thinking is generally confined to physical life on earth, although it may include the preparation of the members of society for a perceived afterlife. It invariably includes criticism of the current state of society and seeks ways to correct or eliminate abuses. Utopianism is characterized by tension between philosophical ideals and the practical realities of society, such as crime and immorality; there is also a conflict between respect for individual freedom and the need to maintain order. Utopian thinking implies a creative process that challenges existing concepts, rather than an ideology or justification for a belief system which is already in place.

Two of Plato’s dialogues, “Republic, and “Laws” contain one of the earliest attempts to define a political organization that will not only allow its citizens to live in harmony, but will provide the education and experience necessary for each citizen to realize his highest potential.

During the nineteenth century, Henri Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, and Etienne Cabet in France, and Robert Owen in England, known as the utopian socialists, popularized the idea of creating small, experimental communities to put philosophical ideals into practice. Marx and Engels, while recognizing that utopianism offered a vision for a better future, dismissed it as lacking a wider understanding of social and political realities which could contribute to actual political change. Bloch and Marcuse made a distinction between “abstract” utopias based on fantasy and dreams, and “concrete” utopias based on critical social theory. Utopianism is considered to originate in the imaginative capacity of the subconscious mind, which is able to transcend conscious reality by projecting images of hopes, dreams and desires.

Utopian ideas, though they may never be fully realized, play an important role in bringing about positive social change. They allow thinkers to distance themselves from the existing reality and consider new possibilities. The optimism that a better society can be achieved provides motivation and a focal point for those involved in bringing about social or political change. Women’s rights and feminism, the Civil Rights movement, the establishment of a welfare system to take care of the poor, the Red Cross, and multiculturalism are all examples of utopian thinking applied to practical life.

Types of Utopia

Economic Utopias

The harsh economic conditions of the nineteenth century and the social disruption created by the development of commercialism and capitalism gave rise to a “utopian socialist" movement. It was characterized by shared ideals: an equal distribution of goods according to need, frequently with the total abolition of money; and citizens laboring for the common good, doing work which they enjoyed, and having ample leisure for the cultivation of the arts and sciences. One such utopia was described in Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward. Another socialist utopia was William Morris' News from Nowhere, written partially in criticism of the bureaucratic nature of Bellamy's utopia. As the socialist movement developed it moved away from utopianism; Marx in particular became a harsh critic of earlier socialisms which he described as “utopian”, saying they were incapable of bringing about substantial political change.

Capitalist utopias, such as the one portrayed in Robert A. Heinlein's The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress or Ayn Rand’s “The Fountainhead,” are generally individualistic and libertarian, are based on perfect market economies, in which there is no market failure. Eric Frank Russell's book The Great Explosion (1963) details an economic and social utopia, the first to mention of the idea of Local Exchange Trading Systems (LETS).

Political and Historical Utopias

Political utopias are ones in which the government establishes a society that is striving toward perfection. These utopias are based on laws administered by a government, and often restrict individualism when it conflicts with the primary goals of the society. Sometimes the state or government replaces religious and family values. A global utopia of world peace is often seen as one of the possible inevitable ends of history.

Religious Utopia

Through history a number of religious communities have been created to reflect the virtues and values they believe have been lost or which await them in the Afterlife. In the United States and Europe during and after the Second Great Awakening of the nineteenth century, many radical religious groups sought to form communities where all aspects of people's lives could be governed by their faith. Among the best-known of these utopian societies wer the Puritans, and the Shaker movement, which originated in England in the 18th century but moved to America shortly after its founding.

The most common utopias are based on religious ideals, and usually required adherence to a particular religious tradition. The Jewish, Christian and Islamic concepts of the Garden of Eden and Heaven may be interpreted as forms of utopianism, especially in theirfolk-religious forms. Such religious "utopias" are often described as "gardens of delight", implying an existence free from worry in a state of bliss or enlightenment. They postulate existences free from sin, pain, poverty and death, and often assume communion with beings such as angels or the houri. In a similar sense the Hindu concept of Moksha and the Buddhist concept of Nirvana may be thought of as a kind of utopia.

Many cultures and cosmogonies include a myth or memory of a distant past when humankind lived in a primitive and simple state of perfect happiness and fulfillment. The various myths describe a time when there was an instinctive harmony between man and nature, and man’s needs were easily supplied by the abundance of nature. There was no motive for war or oppression, or any need for hard and painful work. Humans were simple and pious, and felt themselves close to the gods. These mythical or religious archetypes resurge with special vitality during difficult times, when the myth is not projected towards the remote past, but towards the future or a distant and fictional place (for example, The Land of Cockaygne, a straightforward parody of a paradise), where the possibility of living happily must exist.

Golden Age

Works and Days,' compilation of the mythological tradition by the Greek poet Hesiod, around the eighth century B.C.E., explained that, prior to the present era, there were four progressively most perfect ones.

A medieval poem (c. 1315) , entitled "The Land of Cokaygne" depicts a land of extravagance and excess where cooked larks flew straight into one's mouth; the rivers ran with wine, and a fountain of youth kept everyone young and active.

- Far in the sea, to the west of Spain,

- Is a country called Cokaygne.

- There's no land not anywhere,

- In goods or riches to compare.

- Though Paradise be merry and bright

- Cokaygne is of far fairer sight....

Scientific and Technological Utopias

Scientific and technical utopias are set in the future, when it is believed that advanced science and technology will allow utopian living standards; for example, the absence of death and suffering; changes in human nature and the human condition. These utopian societies tend to change what "human" is all about. Normal human functions, such as sleeping, eating and even reproduction are replaced by artificial means.

Related terms

- Dystopia is a negative utopia: a world wherein utopian ideals have been subverted. example: George Orwell's 1984, Aldous Huxley's Brave New World.

- Eutopia is a positive utopia, roughly equivalent to the regular use of the word "utopia".

- Outopia is argued to be the word "Utopia" was derived from, coming from the latin 'Uo-' for "no" and '-topos' for "place" bringing a meaning of "no place" a fictional, non-realistic place

- Heterotopia, the "other place", with its real and imagined possibilities (a mix of "utopian" escapism and turning virtual possibilities into reality) — example: cyberspace. Samuel R. Delany's novel Trouble on Triton is subtitled An Ambiguous Heterotopia to highlight that it is not strictly utopian (though certainly not dystopian). The novel offers several conflicting perspectives on the concept of utopia.

- Ourtopia combines the English 'our' with the Greek 'topos' to give 'our place'—the nearest thing to a utopian planet that is actually attainable.

Other subcategories, developed by Ruth Levitas, include Arcadias and Cockaygnes.

Examples of utopia

- New Australia A utopian movement founded in 1893 in Paraguay by William Lane

- Plato's Republic (400 B.C.E.) was, at least on one level, a description of a political utopia ruled by an elite of philosopher king s, conceived by Plato . (Compare to his Laws (dialogue)|Laws , discussing laws for a real city.) a Gutenburg text of the book

- The City of God (written 413 – 426 ) by Augustine of Hippo , describes an ideal city, the”eternal”Jerusalem, the archetype of all”Christian”utopias.

- Utopia (Novel)|Utopia ( 1516 ) by Thomas More a Gutenberg text of the book

- Christianopolis|Reipublicae Christianopolitanae descriptio (Beschreibung des Staates Christenstadt) ( 1619 ) by Johann Valentin Andrea|Johann Valentin Andreæ , describes a Christian religious utopia inhabited by a community of scholar-artisans and run as a democracy.

- The Anatomy of Melancholy ( 1621 ) by Robert Burton (scholar)|Robert Burton , a utopian society is described in the preface.

- The City of the Sun ( 1623 ) by Tommaso Campanella depicts a theocratic and communist society.

- The New Atlantis ( 1627 ) by Francis Bacon (philosopher)|Francis Bacon

- Oceana ( 1656 the Integral, praising the efficiency, the rationality, and the happiness that life within the confines of the One State can bring to those worlds the Integral will someday visit.

- Aldous Huxley 's Brave New World ( 1932 ) can be considered an example of pseudo-utopian satire (see also dystopia ). One of his other books, Island (novel)|Island ( 1962 ), demonstrates a positive utopia.

- Shangri-La described in the novel Lost Horizon by James Hilton ( 1933 )

- Islandia ( 1942 ), by Austin Tappan Wright , an imaginary island in the Southern Hemisphere, a utopian containing many Arcadia (utopia)|Arcadian elements, including a rejection of technology.

- B. F. Skinner 's Walden Two ( 1948 )

- The Cloud of Magellan ( 1955 ) by Stanisław Lem

- Andromeda Nebula ( 1957 ) is a classic communist utopia by Ivan Efremov

- The Great Explosion , Eric Frank Russell 1963 In the last section setting out a workable utopian economic system leading to a different social and political reality.

- The Corridors of Time by Poul Anderson (1965)

- Star Trek ( 1966 ) science fiction television series by Gene Roddenberry

- The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas ( 1969 ), by Ursula K. Le Guin

- The Kingdom of Zeal in Chrono Trigger ( 1995 ) is a utopian society.

- |The Hedonistic Imperative ( 1996 ), an online manifesto by David Pearce , outlines how genetic engineering and nanotechnology will abolish suffering in all sentient life.

- The Kin of Ata Are Waiting for You ( 1997 ) by Dorothy Bryant

- The Matrix ( 1999 ), a film by the Wachowski brothers , describes a virtual reality controlled by artificial intelligence such as Agent Smith . Smith says that the first Matrix was a utopia, but humans rejected it because they "define their reality through misery and suffering." Therefore, the Matrix was redesigned to simulate human civilization with all its suffering.

- Equilibrium ( 2002 ), a film describing a future in which feelings are forbidden. *”Fahrenheit 451” by Ray Bradbury .

- Xen: Ancient English Edition , ( 2004 ) "translated" by D.J. Solomon

- Ensaio sobre a Lucidez ("Treatise on Lucidity") by José Saramago ( 2004 ), describes a city where there is 83% of blank votes at an election.

- Globus Cassus, ( 2004 ), is a project for the transformation of the Earth into a large, hollow structure inhabited on the inside

- The first story arc in the seventh season ( 2004 - 2005 ) of the supernatural dramedy series Charmed involves the transformation of the world into utopia through the fear of a common enemy.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Kateb, G. “Utopianism and Its Enemies” New York, Free Press, 1963.

- Kumar, Krishan (1991) Utopianism .Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-335-15361-5

- Kumar, K (1987) Utopia and Anti-utopia in Modern Times Oxford: Blackwell. 1979. ISBN 0-631-16714-5

- Levitas, Ruth. Concept of Utopia (Utopianism & Communitarianism) .Syracuse University Press; 1st ed. edition, 1991.

- Mannheim, Karl. Ideology and Utopia: An Introduction to the SOCIOLOGY (740) of Knowledge. Harvest Books; Reprint edition, 1955.

- Manuel, Frank & |Manuel, Fritzie Utopian Thought in the Western World . Oxford: Blackwell, 1979. ISBN 0-674-93185-8

External Links

- Full text of Thomas More's Utopia from Project Gutenberg

- Utopia - The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2001

- Society for Utopian Studies is the Main Page for the Society for Utopian Studies, an international, interdisciplinary association devoted to the study of utopianism in all its forms, with a particular emphasis on literary and experimental utopias.

- [http://www.abolitionist-soci

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.