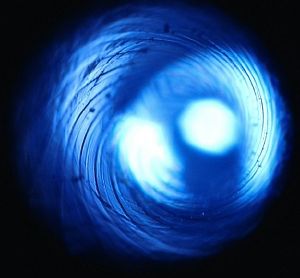

A rifle is a firearm with a barrel that has a helical groove or pattern of grooves ("rifling") cut into the barrel walls. This pattern is known as "rifling," and produces raised areas or "lands," which make contact with the projectile (usually a bullet), imparting spin around an axis corresponding to the center line of the projectile. When the projectile leaves the barrel, the conservation of angular momentum, as in a spinning gyroscope, improves accuracy and range, in the same way that a properly thrown American football or rugby ball behaves. The word "rifle" originally referred to the grooving, and a rifle was called a "rifled gun." Rifles are used in warfare, competitive target shooting, hunting and sport shooting. Artillery pieces used in warfare, including 12-inch or larger naval guns and the like, also usually have rifled barrels.

Our interest and concentration in this article will be confined to shoulder-fired rifles, not in artillery pieces.

Typically, a bullet is propelled by the contained deflagration (rapid burning) of gunpowder; this was originally black powder, later Cordite, and now smokeless powder, usually made of nitrocellulose or a combination of nitrocellulose and nitroglycerin. Other means such as compressed air are used in air rifles, which are popular for vermin control, hunting small game, casual shooting ("plinking"), and some target competitions.

Types of Rifles

Theye are numerous types of rifles today, based on the gun mechanism.

Bolt Action Rifles

The first is the bolt action rifle. In this action type, there is a turning bolt that has lugs that lock into recesses in the receiver part of the rifle, at either the head of the bolt, or (less commonly) the rear of the bolt, or (in the case of .22 rimfire and similar low-power rifles) using the base of the bolt handle. In this type of rifle, the shooter manipulates the bolt handle, turning it up and pulling it back to eject the spent cartridge case. Bolt action rifles can be either single-shots—meaning that they have no magazine and have to be loaded manually after each firing—or they can have magazines holding one or more fresh cartridges. If it is a magazine rifle and there is a cartridge in the magazine, the bolt then can be pushed forward and turned down, locking it in place and the gun will be ready to fire again. Some single shot bolt action rifles have manual cocking, meaning that the cocking piece needs to bre pulled back and set manually before the gun can be fired. Such manual cocking often appears on guns designed to be used by young shooters, as this is condsidered to be an additional safety feature of such guns. So called youth guns are usually single shots, usually bolt action, usually made smaller in order to fit the body size of a younger person, and often requiring manual cocking.

Probably the greatest designer of turnbolt-type bolt action rifles was the German Paul Mauser, and Mauser rifles bear his name to this day. His designs culminated in the 1898 Mauser, which was Germany's primary battle weapon through two World Wars. Mauser's rifle designs also serve as the foundation of nearly all subsequent centerfire turnbolt-type bolt action rifle designs to today—they can be thought of as modifications of Mauser's work—including the U.S. made 1903 Springfield, the pattern '13 and '17 Enfields, the Winchester Models 54 and 70 sporting rifles, the Remington models 30, 721 and 700, the Ruger Model 77, the Czech Brno, the Dakota, and numerous others.

Single shot bolt action rifles can be relatively inexpensive, about US$100 for a youth gun, or cost thousands of dollars, as in ultra high quality target rifles made for the most stringent rifle competition, especially bench rest shooting.

Bolt action rifles are the most common action type used in hunting, plinking (informal shooting), and target competition, although they are now mostly obsolete for military use except for long-range sniper weapons. They are available in a full range of caliber sizes, from the smallest (such as the .22 short rimfire) to the largest (such as the .50 caliber Browning Machine Gun cartridge or the .700 Holland & Holland Nitro Express). They can also be made to be the most accurate of all rifles.

Break Open Rifles

A second type of rifle is the break open rifle. These can be either single shots or double rifles (similar to a double barrel shotgun). This gun action-type opens on a hinge pin, with the barrel (and its chamber) opening to the operator. There is a latch in the gun frame that holds the gun closed with the barrel in firing position until the handle of the latch is pushed ot the open position.

Break open guns can have either extractors, which lift the shell out of the chamber slightly (about ¼ to ½ inch) so that it can be manually grabbed and removed, or ejectors, which are spring loaded devices that actively eject the cartridge case from the gun when the gun is broken open. Extractors are often made automatic, so that they perform as extractors if the cartridge in the barrel has not been fired, or as ejectors if it has been fired. (This is true of shotguns too; which often have selective automatic ejectors, ejecting the spent case from whichever, or both, of the barels that have been fired, and performing as an extractor for any unfired cases.)

The single shot break-open rifle is quite similar to a break-open single shot shotgun. This gun often has an exposed hammer that needs to be manually cocked before the rifle can be fired. The rifle is loaded manually, by breaking open the rifle, removing the spent cartridge case, and inserting a fresh round into the chamber. The rifle is then closed and it is ready to be cocked (if manual cocking is necessary) and fired. A feature of such rifles is that they often have interchangeable barrels, meaning that the shooter can have numerous calibers of rifle on the same gun frame, simply by switching to a barrel of a different caliber. Break open single shot rifles are generally relatively inexpensive, in the range of US$150 - 300, and although not so often seen, are not rare in the United states.

The second type of break open rifle is the double barrel. In this gun type there are two barrels fastened together into one unit, and each barrel is loaded separately, so that two shots are available before the gun needs to be reloaded. After the first shot is fired, the second shot is fired when the trigger is pulled again (in single-trigger type double barrels) or when the second trigger is pulled (in double trigger guns).

As with shotguns, there are two differnt configurations of double barrel rifles: the side by side and the over under. In the side by side, the two barrels are next to each other horizontally, and in the over under one barrel is above the other vertically. Both types have certain advantages. The side by side does not need to open on as large an arc so that both barrels can be loaded or unloaded. The over under presents a narrower sighting plane to the shooter. Most side by side double rifles have double triggers; single triggers are more common on over unders.

Double rifles of either type are the most expensive rifles made. They start at US $5000 or more, and can go up to US$50,000 or $100,000 or even more—a Holland & Holland or Boss (British) side by side double can go for £90,000 (about US$180,000) or more. They are often custom made, with a substantial amount of hand labor put into them. They are rare in America, but were commonly used in Europe. They were especially favored in African hunting, usually in heavy calibers, for the largest and most dangerous game. They are not especially accurate—it takes a great deal of expensive work, called [regulation]], to get the two barrels to shoot to the same point—but are designed to get off two very quick shots at relatively short distances. For gun aficonados, double rifles often represent the pinnacle of the gunmaking arts.

Lever Action Rifles

The lever action rifle was one of the first repeater rifle designs. The most common version is the Winchester Model 94—the gun often seen in Western movies. Operating the lever, which is under the butt stock and behind the trigge guard, ejects the spent shell and loads a fresh csrtridge from the magazine into the chamber for firing. Many lever action rifles have an exposed hammer that can be lowered without firing the round and then needs to be cocked manually for firing.

Lever action rifles are made in calibers from .22 rimfire to larger, including (for some makes and models) the .30-06 or .45-70, but the largest or most powerful of rifles are usually not made in lever actions—this action type is not strong enough for the heaviest or most powerful cartridges or loads. Some, such as the Winchester 94, are top ejecting, meaning that a scope cannot be mounted directly above the bore. Others, like the Marlin Model 336, are side ejecting.

In a lever action rifle there is usually a tubular magazine under the rifle barrel. Since the cartridges are lined up in the magazine with the tip of one facing the base of another, there is a danger with sharp-pointed bullets that the point of one might hit the primer of the one ahead of it and set it off, so ammunition with sharp-pointed bullets must not be used in the tubular magazines of lever rifles.

There are lever action rifles with non-tubular magazines, so that problem does not apply to them. One is the Savage Model 99; none of those have tubular magazines and some had a rotary magazine, and others have simple box-type magazines. The Browning Lever Action Rifle (BLR) also has a box-type magazine, and is availoable in powerful calibers such as .30-06 and others. The Savage is unlike the others in not having an exposed hammer.

Winchester also made the Model 95 lever action rifle in such powerful calibers as .30-06 Springfield and .405 Winchester. It had a box-type magazine. Later on Winchester also made the Model 88. It had a box-type magazine, a one-piece streamlined stock and a rotating front-locking bolt like a bolt action rifle but that was operated by a lever. It was an entirely different rifle than the classic Winchester lever actions and was available in .308 Winchester, .284 Winchester, .358 Winchester, and some other calibers.

Probably the most common cartridge ever used in lever action rifles—especially the Winchester Model '94 and Marlin Model 336 ones—is the 30-30 Winchester. And, although it is now near-obsolete and has mostly been supplanted by the better .308 Winchester, the .300 Savage in a Savage Model 99 rifle was once a very commonly used hunting rifle for deer, black bear, elk, moose and other big game. Some lever action rifles, such as the Winchester 95, have also been used by various armed forces as military weapons.

Marlin, Winchester, and Savage lever action rifles were recently available for about $450, but Winchester prices are now rising because WWinchester rifles have been discontinued. The Browning BLR is about $800 today.

Pump Action Rifles

In a pump action rifle (also known as slide action, and sometimes a trombone action), the forestock is manually pulled back and then manually pushed forward to operate the gun mechanism. This action expels the spent case or shell and then takes a fresh cartridge from the magazine and chambers it in the barrel. It also cocks the firing mechanism of the rifel so that it is ready to fire when the trigger is pulled. Although pump action rifles have been made by various manufacturers, Remington has dominated in this type. Browning also make a pump rifle tne BPR. Pump-type rifles can have either tubular or box-type (or clip-type) magazines, and have been available in calibers as powerful as the .30-06 and .35 Whelen. Many .22 rimfire rifles in pump action have also been made.

This rifle type is popular in North America, but—for whatever reason—has been almost unknown in Europe, Asia, or Africa. It is the fastest-operating of all the manually operated rifles.

Autoloading Rifles

An autoloading rifle operates on the principle of using either the recoil of firing (recoil operated, or "blowback" operated) or some of the gas generated by firing (gas operated) to operate the gun mechanism to eject the spent shell and load a fresh cartridge from the magazine. The rifle can then be fired again simply by pulling the trigger. This type of rifle is sometimes mistakenly called an "automatic" but a true automatic is a machine gun, which means it continues firing as long as fresh cartridges are available to it and the trigger is kept pulled. A gun which reloads itself, but in which the trigger must be pulled for each shot is properly called an autoloader or semi-automatic.

The first great military autoloader was the gas operated U.S. M-1 Garand, in .30-06 caliber (John Garand himself was Canadian). It was used in WWII, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. General George S Patton called the M-1 "The greatest battle implement ever devised". Since that time a lare number of autoloading military rifles have been built and used all over the world.

Besides military rifles, very many sporting autoloading rifles have been made. The most popular .22 rimfire rifles are blowback type ones,[1] such as the Ruger 10/22, and many others. Remington, Browning, Benelli, and many other manufacturers have made and continue to make autoloading centerfire rifles, on various designs. Some have tubular magazines and others have box magazines; the Ruger 10/22 has a rotary type removable box magazine.

Assault Weapons and Machine Guns

An assault weapon is a military weapon that has the ability to be operated either as a semiautomatic gun (the trigger must be pulled for every shot) or as a true automatic (the gun continues firing as long as the trigger is pulled and there is fresh ammunition in the magazine), with the switch of a lever. Some assault weapons have a multiple position switch: semi automatic, short burst of about 3 to 5 shots, or fully automatic. The Russian AK-47 is the best known and most widely used military assault weapon in the world; millions have been manufactured in many different places in the world: Russia, the Eastern Bloc, China, Egypt, and elsewhere. It was originally in caliber 7.62 x 39mm; more recently some have been made in a .22 caliber version known as

Overview

Originally, in military use, rifles were sharpshooter weapons, while the regular infantry made use of the greater firepower of massed muskets, which fired round musket balls of calibers up to 0.75 inch (19 mm). Benjamin Robins, an English mathematician, realized that an extruded bullet would retain the mass and kinetic force of a musket ball, but would slice through the air with much greater ease. The innovative work of Robins and others would take until the end of the 18th century to gain acceptance.

By the mid-19th century, however, manufacturing had advanced sufficiently that the musket was replaced by a range of rifles—generally single-shot, breech-loading—designed for aimed, discretionary fire by individual soldiers. Then, as now, rifles had a stock, either fixed or folding, to be braced against the shoulder when firing. Early military rifles, such as the Baker rifle were shorter than the day's muskets, and usually the weapon of a marksman. Until the early 20th century rifles tended to be very long—an 1890 Martini-Henry was almost six feet (1.8 m) in length with a fixed bayonet. The demand for more compact weapons for cavalrymen led to the carbine, or shortened rifle.

History

Origins

Muskets were smooth-bore, large caliber weapons using ball-shaped ammunition fired at relatively low velocity. Due to the high cost and great difficulty of precision manufacturing, and the need to load readily from the muzzle, the musket ball was a loose fit in the barrel. Consequently on firing the ball bounced off the sides of the barrel when fired and the final direction on leaving the muzzle was unpredictable. (In the late 1800s, the term "rifled musket" was used to distinguish between smoothbore and rifled long arms.)

The performance of muskets were sufficient in early warfares primarily because of the styles of warfare at the time. At the time, European soldiers tended to stand in stationary long lines and fire at the opposing forces, which meant that you did not necessarily have to have the bullet going in the direction you wanted to hit an opponent.

The origins of rifling are difficult to trace, but some of the earliest practical experiments seem to have occurred in Europe during the fifteenth century. Archers had long realized that a twist added to the tail feathers of their arrows gave them greater accuracy. Early muskets produced large quantities of smoke and soot, which had to be cleaned from the action and bore of the musket frequently; either the action of repeated bore scrubbing, or a deliberate attempt to create 'soot grooves' might also have led to a perceived increase in accuracy, although no-one knows for sure. True rifling dates from the mid-15th century, although the precision required for its effective manufacture kept it out of the hands of infantrymen for another three and a half centuries, when it largely replaced the unrifled musket as the primary infantry weapon.

First designs

Some early rifled guns were created with special barrels that had a twisted polygonal shape. Specially-made bullets were designed to match the shape so the bullet would grip the rifle bore and take a spin that way.These were generally limited to large caliber weapons and the ammunition still did not fit tightly in the barrel. Many experimental designs used different shapes and degrees of spiraling. Although uncommon, polygonal rifling is still used in some weapons today with one example being the Glock line of pistols. Unfortunately, many early attempts resulted in dangerous backfiring, which could lead to destruction of the weapon and serious injury to the person firing.

19th Century

Gradually, rifles appeared with cylindrical barrels cut with helical grooves, the surfaces between the grooves being called "lands." The innovation shortly preceded the mass adoption of breech-loading weapons, as it was not practical to push an overbore bullet down through a rifled barrel, only to then (try to) fire it back out. The dirt and grime from prior shots was pushed down ahead of a tight bullet or ball (which may have been a loose fit in the clean barrel before the first shot), and, of course, loading was far more difficult, as the lead had to be deformed to go down in the first place, reducing the accuracy due to deformation. Several systems were tried to deal with the problem, usually by resorting to an under-bore bullet that expanded upon firing.

The original muzzle-loading rifle, with a closely fitting ball to take the rifling grooves, was loaded with difficulty, particularly when foul, and for this reason was not generally used for military purposes. Even with the advent of rifling the bullet itself didn't change, but was wrapped in a greased, cloth patch to grip the rifling grooves.

The first half of the nineteenth century saw a distinct change in the shape and function of the bullet. In 1826 Delirque, a French infantry officer, invented a breech with abrupt shoulders on which a spherical bullet was rammed down until it caught the rifling grooves. Delirque's method, however, deformed the bullet and was inaccurate.

Minié

One of the most famous was the Minié system, which relied on a conical bullet (known as a Minié ball) with a hollow at the base of the bullet that caused the base of the round to expand from the pressure of the exploding charge and grip the rifling as the round was fired. Minié system rifles, notably the U.S. Springfield and the British Enfield of the early 1860s, featured prominently in the U.S. Civil War, due to the enhanced power and accuracy. The better seal gave more power, as less gas escaped past the bullet, which combined with the fact that for the same bore (caliber) diameter a long bullet was heavier than a round ball. Enhanced accuracy came from the expansion to grip the rifling, which spun the bullet more consistently.

Another important area of development was the way that cartridges were stored and used in the weapon. The Spencer repeating rifle was a breech-loading manually operated lever action rifle, that was adopted by the United States and over 20,000 were used during the Civil War. It marked the first adoption of a removable magazine-fed infantry rifle by any country. The design was completed by Christopher Spencer in 1860. It used copper rimfire cartridges stored in a removable seven round tube magazine, enabling the rounds to be fired one after another, and which, when emptied, could be exchanged for another.

As the bullet enters the barrel, it screws itself into the rifling, a process that gradually wears down the barrel, and more rapidly causes the barrel to heat up. Therefore, some machine-guns are equipped with quick-change barrels that can be swapped every few thousand rounds, or, in earlier designs, were water-cooled. Unlike older carbon steel barrels, which were limited to around 1,000 shots before the extreme heat caused accuracy to fade, modern stainless steel barrels for target rifles are much harder, and so wear far less, allowing tens of thousands of rounds to be fired before accuracy drops. (Many shotguns and small arms have chrome-lined barrels to reduce wear and enhance corrosion resistance. This is rare on rifles designed for extreme accuracy, as the plating process is difficult and liable to reduce the effect of the rifling.) Hardened armor piercing bullets produce wear rapidly, which necessitates that they are encased in a softer metal jacket (typically Copper) or Teflon.

Bullet design

Over the 19th century, bullet design also evolved, the slugs becoming gradually smaller and lighter. By 1910 the standard blunt-nosed bullet had been replaced with the pointed, 'spitzer' slug, an innovation that increased range and penetration. Cartridge design evolved from simple paper tubes containing black powder and shot to sealed brass cases with integral primers for ignition, while black powder itself was replaced with cordite, and then other smokeless mixtures, propelling bullets to higher velocities than before.

The increased velocity meant that new problems arrived, and so bullets went from being soft lead to harder lead, then to copper jacketed, in order to better engage the spiraled grooves without "stripping" them in the same way that a screw or bolt thread would be stripped if subjected to extreme forces.

20th Century

As mentioned above, rifles were initially single-shot, muzzle-loading weapons. During the 18th century, breech-loading weapons were designed, which allowed the rifleman to reload while under cover, but defects in manufacturing and the difficulty in forming a reliable gas-tight seal prevented widespread adoption. During the 19th century, multi-shot repeating rifles using lever, pump or linear bolt actions became standard, further increasing the rate of fire and minimizing the fuss involved in loading a firearm. The problem of proper seal creation had been solved with the use of brass cartridge cases, which expanded in an elastic fashion at the point of firing and effectively sealed the breech while the pressure remained high, then relaxed back enough to allow for easy removal. By the end of the 19th century, the leading bolt-action design was that of Paul Mauser, whose action—wedded to a reliable design possessing a five-shot magazine—became a world standard through two world wars and beyond. The Mauser rifle was paralleled by Britain's ten-shot Lee-Enfield and America's 1903 Springfield Rifle models (the latter pictured above). The American M1903 closely copied Mauser's original design.

The advent of massed, rapid firepower and of the machine gun and the rifled artillery piece was so quick as to outstrip the development of any way to attack a trench defended by riflemen and machine gunners. The carnage of World War I was perhaps the greatest vindication and vilification of the rifle as a military weapon. By World War II, military thought was turning elsewhere, towards more compact weapons.

WWII

Experience in World War I led German military researchers to conclude that long-range aimed fire was less significant at typical battle ranges of 500 m. As mechanisms became smaller, lighter and more reliable, semi-automatic rifles, including the American M1 Garand, appeared. World War II saw the first mass-fielding of such rifles, which culminated in the Sturmgewehr 44, the first assault rifle and one of the most significant developments of 20th century small-arms. Today, most military rifles throughout the world are semi-automatic types; the exception is some highly refined bolt action rifles designed for extremely accurate long range shooting—these are often known as sniper rifles.

By contrast, civilian rifle design has, for the most part, not significantly advanced since the early part of the 20th century. Modern hunting rifles have either wood or fiberglass and carbon fibre stocks and more advanced recoil pads, but are fundamentally the same as infantry rifles from 1910. Many modern sniper rifles can trace their ancestry back for well over a century, and the Russian 7.62 x 54 mm cartridge, as used in the front-line SVD Dragunov sniper rifle, dates from 1891.

History of use

Muskets were used for comparatively rapid, unaimed volley fire, and the average conscripted soldier could be easily trained to use them. The (muzzle-loaded) rifle was originally a sharpshooter's weapon used for targets of opportunity and sniper fire. During the Napoleonic Wars, the British 95th Regiment (Green Jackets) and 60th Regiment (Royal American) used the rifle to great effect during skirmishing. Because of a slower loading time than a musket, they were not adopted by the whole army. The adoption of cartridges and breech-loading in the 19th century was concurrent with the general adoption of rifles. In the early part of the 20th century, soldiers were trained to shoot accurately over long ranges with high-powered cartridges. World War I Lee-Enfields rifles (among others) were equipped with long-range 'volley sights' for massed firing at ranges of up to a mile (1600 m). Individual shots were unlikely to hit, but a platoon firing repeatedly could produce a 'beaten ground' effect similar to light artillery or machine guns; but experience in WWI showed that long-range fire was best left to them.

During and after WW II it became accepted that most infantry engagements occur at ranges of less than 500 m; the range and power of the large rifles was "overkill"; and the weapons were heavier than the ideal. This led to Germany's development of the 7.92 x 33 mm Kurz (short) round, the Karabiner 98, the MKb-42, and ultimately, the assault rifle. Today, an infantryman's rifle is optimised for ranges of 300 m or less, and soldiers are trained to deliver individual rounds or bursts of fire within these distances. The application of accurate, long-range fire is the domain of the sniper in warfare, and of enthusiastic target shooters in peacetime. The modern sniper rifle is usually capable of accuracy better than one minute of angle arcminute (300 μrad).

In recent decades, large-caliber anti-materiel sniper rifles, typically firing .50BMG (12.7 mm) and 20mm caliber cartridges, have been developed. The US Barrett M82A1 is probably the best known such rifle. These weapons are typically used to strike critical, vulnerable targets such as computerized command and control vehicles, radio trucks, radar antennae, vehicle engine blocks and the jet engines of enemy aircraft. Anti-materiel rifles can be used against human targets, but the much higher weight of rifle and ammunition, and the massive recoil and muzzle blast, usually make them less than practical for such use. The Barrett M82 is credited with a maximum effective range of 1800 m (1.1 mi); and it was with a .50BMG caliber McMillan TAC-50 rifle that Canadian Corporal Rob Furlong made the longest recorded confirmed sniper kill in history, when he shot a Taliban insurgent at a range of 2,430 metres (1.51 miles) in Afghanistan during Operation Anaconda in 2002.

Modern Civilian Use

Currently, rifles are the most common firearm in general use for hunting purposes (with the exception of bird hunting where shotguns are favored). Use of rifles in competitve shooting sports is also very common, and includes Olympic events. There are many different types of shooting competitions, each with its specific rules and its characteristic type of rifle. Military-style rifles in semi-automatic such as the AR-15 have become popular in the United States and are now sometimes used for hunting, although bolt action, lever action, and other rifle types are more commonly used.

See also

- British military rifles

- Pistol

- Shotgun

- Antique guns

- Rifle range

- Gun safety

- Rifle grenade

- List of rifle cartridges

- Rifling

- Service rifle

- List of Countries and Their Service Rifles

Kinds of rifles

- Air rifle

- Spencer rifle

- Automatic rifle

- Assault rifle; List of assault rifles

- Anti-materiel rifle

- Battle rifle

- Carbine

- Double rifle

- Lloyd rifle

- Musket

- Repeating rifle

- Recoilless rifle

- Sniper rifle; List of sniper rifles

- Long rifle

- Lever-action

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ In a blowback rifle, the breechblock is a relatively heavy moving bolt, held in place by a spring. This works for low-power cartridges, such as the .22 rimfire and some low-power pistol cartridges. More powerful cartridges require some locking mechanism, sometimes called a retarded blowback, or a bolt that is operated by the gas system, as in the M-1.