Difference between revisions of "Reductionism" - New World Encyclopedia

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) |

m (→References) |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

==Varieties of reductionism== | ==Varieties of reductionism== | ||

| − | + | Most reductionist claims in philosophy can be put in one of two categories, which are sometimes called ontological reductionism and theoretical reductionism. | |

===Ontological reductionism=== | ===Ontological reductionism=== | ||

| − | + | Some claims about reductionism concern things in the world, such as objects, properties, and events. These claims state that one thing or set of things can be reduced to some other, more basic thing or set of things. Consider a particular example: | |

| − | |||

| − | + | <blockquote>The population of Springfield is nothing more than Adam, Alex, Alice, Anna...</blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In this claim, a thing (the population of Springfield) is reduced to a set of individual people. The idea is that that set of people is all there is to 'the population', and everything that's true about the latter comes down to something that's true about the former. For example, if it's true that the population is shrinking, this might be explained by saying that Adam and Alex left town. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Note that there's an asymmetry in the relation between those two facts: if Adam and Alex leave town (and everyone else stays put), then it's necessarily true that the population of Springfield shrinks. But if the population of Springfield shrinks, it's not necessarily true that Adam and Alex left; it might instead be the case that Alice and Anna left. This asymmetry is indicative of the fact that the set of people is more 'basic' than the population. So the reductionist claim doesn't merely state that there's some close relation between the two, it further claims that one is more fundamental. You can understand everything about the population by understanding what's going on with Adam, Alex, Alice, Anna etc., but not the other way around. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | One subtle issue about ontological reductionism is whether one 'reduces away' the thing or things in question. In the above example, it intuitively seems that even though the population reduces to the set of people, the population still exists. But consider a different example: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <blockquote>Santa Claus is nothing more than a story told to children.</blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | As before, everything that's true about Santa Claus comes down to something true about the story. If it's true that Santa Claus lives on the North Pole, that's just because that's part of the story. But in this case, the fact that Santa Claus is reduced to a story seems to mean that Santa does not exist. Putting the matter metaphorically, he has been reduced away. | |

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===Theoretical reductionism=== |

| − | + | A distinct but related type of reduction can hold between ''theories'' - where 'theories' are understood as sets of claims. For example, it is often claimed (though not without controversy) that biology will ultimately be reduced to chemistry, and chemistry in turn will be reduced to physics. There are two dominant models of how this is supposed to work, one expounded by Ernest Nagel and the other by John Kemeny and Paul Oppenheim. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ====The Nagel Model==== | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ====The Kemeny-Oppenheim Model==== | |

== History == | == History == | ||

| Line 61: | Line 45: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * | + | *Churchland, P.S. (1986) ''Neurophilosophy'', Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. |

| − | * | + | *Kemeny, J. and Oppenheim, P. (1956) ‘On Reduction’, ''Philosophical Studies'' 7: 6–18. |

| − | * | + | *Kim, J. (1998) 'Reduction, Problems of'. In E. Craig (Ed.), ''Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy.'' London: Routledge |

| − | + | *Nagel, E. (1961) ''The Structure of Science''. New York: Harcourt Press. | |

| − | *Nagel, E. (1961) ''The Structure of Science''. New York | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

Revision as of 00:57, 24 August 2007

In philosophy, reductionism is a theory that asserts that the nature of complex things is reduced to the nature of sums of simpler or more fundamental things. This can be said of objects, phenomena, explanations, theories, and meanings.

Reductionism is often understood to imply the unity of science. For example, fundamental chemistry is based on physics, fundamental biology and geology are based on chemistry, psychology is based on biology, sociology is based on psychology, and political science, anthropology, and even economics are based on sociology. The first two of these reductions are commonly accepted but the last three or four — psychology to biology and so on — are controversial. For example, aspects of evolutionary psychology and sociobiology are rejected by those who claim that complex systems are inherently irreducible or holistic. Some strong reductionists believe that the behavioral sciences should become "genuine" scientific disciplines by being based on genetic biology, and on the systematic study of culture (cf. Dawkins's concept of memes).

In his book The Blind Watchmaker, Richard Dawkins introduced the term "hierarchical reductionism" (p. 13) to describe the view that complex systems can be described with a hierarchy of organizations, each of which can only be described in terms of objects one level down in the hierarchy. He provides the example of a computer, which under hierarchical reductionism can be explained well in terms of the operation of hard drives, processors, and memory, but not on the level of AND or NOR gates, or on the even lower level of electrons in a semiconductor medium.

Varieties of reductionism

Most reductionist claims in philosophy can be put in one of two categories, which are sometimes called ontological reductionism and theoretical reductionism.

Ontological reductionism

Some claims about reductionism concern things in the world, such as objects, properties, and events. These claims state that one thing or set of things can be reduced to some other, more basic thing or set of things. Consider a particular example:

The population of Springfield is nothing more than Adam, Alex, Alice, Anna...

In this claim, a thing (the population of Springfield) is reduced to a set of individual people. The idea is that that set of people is all there is to 'the population', and everything that's true about the latter comes down to something that's true about the former. For example, if it's true that the population is shrinking, this might be explained by saying that Adam and Alex left town.

Note that there's an asymmetry in the relation between those two facts: if Adam and Alex leave town (and everyone else stays put), then it's necessarily true that the population of Springfield shrinks. But if the population of Springfield shrinks, it's not necessarily true that Adam and Alex left; it might instead be the case that Alice and Anna left. This asymmetry is indicative of the fact that the set of people is more 'basic' than the population. So the reductionist claim doesn't merely state that there's some close relation between the two, it further claims that one is more fundamental. You can understand everything about the population by understanding what's going on with Adam, Alex, Alice, Anna etc., but not the other way around.

One subtle issue about ontological reductionism is whether one 'reduces away' the thing or things in question. In the above example, it intuitively seems that even though the population reduces to the set of people, the population still exists. But consider a different example:

Santa Claus is nothing more than a story told to children.

As before, everything that's true about Santa Claus comes down to something true about the story. If it's true that Santa Claus lives on the North Pole, that's just because that's part of the story. But in this case, the fact that Santa Claus is reduced to a story seems to mean that Santa does not exist. Putting the matter metaphorically, he has been reduced away.

Theoretical reductionism

A distinct but related type of reduction can hold between theories - where 'theories' are understood as sets of claims. For example, it is often claimed (though not without controversy) that biology will ultimately be reduced to chemistry, and chemistry in turn will be reduced to physics. There are two dominant models of how this is supposed to work, one expounded by Ernest Nagel and the other by John Kemeny and Paul Oppenheim.

The Nagel Model

The Kemeny-Oppenheim Model

History

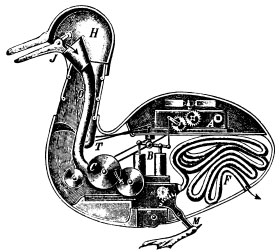

The idea of reductionism was introduced by Descartes in Part V of his Discourses (1637). Descartes argued the world was like a machine, its pieces like clockwork mechanisms, and that the machine could be understood by taking its pieces apart, studying them, and then putting them back together to see the larger picture. Descartes was a full mechanist, but only because he did not accept the conservation of direction of motions of small things in a machine, including an organic machine. Newton's theory required such conservation for inorganic things at least. When such conservation was accepted for organisms as well as inorganic objects by the middle of the 20th century, no organic mechanism could easily, if at all, be a Cartesian mechanism.

See also

- holism

- emergentism

- scientific reductionism

- theology

- Aristotle

- Philosophy of Mind

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Churchland, P.S. (1986) Neurophilosophy, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kemeny, J. and Oppenheim, P. (1956) ‘On Reduction’, Philosophical Studies 7: 6–18.

- Kim, J. (1998) 'Reduction, Problems of'. In E. Craig (Ed.), Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. London: Routledge

- Nagel, E. (1961) The Structure of Science. New York: Harcourt Press.

External links

- John Dupré: The Disunity of Science, an interview at the Galilean Library covering criticisms of reductionism.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.