Peasant

Peasant revolts coincided with the Protestant Reformation, and also the development of stronger classes and improved abilities of peasants to own have improved political rights. Much contemporary thought is based on the European experience alone, though there is variation in the continued development of farm workers around the world.

Background

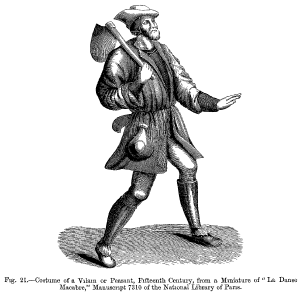

Historically, peasant is a word for farmer. But in the world before the development of individual ownership, free trade and democracy, to be a peasant meant to stay alive. All land was owned by various aristocracy or state governments, and as the modern division of labor and industry had not developed, the way to eat was to cultivate the land. Peasants were part of their land and depended on it.(illustration, above right). A peasant had to be a jack-of-all trades, handy at everything and able to solve all problems that came up. Peasants lived within agricultural time; the "world-time," in Fernand Braudel's term, of politics and economics did not directly affect the peasant. Peasants typically made up the majority of the population. In modern society, where a market economy has taken root, the term may be more loosely referring to the traditionalist rural population where land is chiefly held by smallholders, peasant proprietors.

A rural peasant population differs enormously in its values and economic behavior from an urban worker population. Peasants tend to more conservative than urbanites, and are often very loyal to inherited power structures that define their rights and privileges and protect them from interlopers, despite their generally lower status within them.

Peasant societies developed strong social support networks. Especially in harder climates, members of the community who had a poor harvest or suffered some form of hardship often have been taken care of by the rest of the community. Loyalties and vengeance both ran very deep. Peasant communities can be difficult to access or understand by outsiders.

Peasant societies often have had very stratified social hierarchies within them.

Some commentary has been made that in a barter economy, peasants characteristically had a different attitude to work than peasants— or towndwellers— in a money economy would. Often such societies have been markedly less competative.

Fernand Braudel devoted the first volume of his major work, Civilization and Capitalism 15th–18th Century to the largely silent and invisible world that existed below the market economy, in The Structures of Everyday Life.

Since the literate classes who left the most record tended to dismiss the peasants as figures of coarse appetite and rustic comedy, "peasant" may have had a pejorative rather than descriptive connotation in historical memory. However, it was not always that way; peasants were once viewed as pious and seen with respect and pride. Life was hard for peasants, but before modern technology and a money economy, life was hard for everyone. Society was theorized as organized in three "estates": those who work, those who pray and those who fight.

The position of the medieval European Peasant diverges

The relative position of Western European peasants greatly improved after the Black Death unsettled medieval Europe, granting far greater economic and political power to those peasants fortunate enough to survive the cataclysm. In the wake of this disruption to the established hierarchy, later centuries saw the invention of the original printing presses, widespread literacy and the enormous social and intellectual changes of the Protestant Reformation and the Enlightenment. The evolution of ideas in an environment of relatively widespread literacy laid the groundwork for the Industrial Revolution, which enabled mechanically and chemically augmented agricultural production while simultaneously increasing the demand for factory workers in cities. The factory workers were low skilled and easy to replace and quickly came to occupy the same socio-economic stratum as the original medieval peasants. The tension between the interests of these two groups forms an underlying context for much of the social and economic debate of the past century and a half. Much of this dialogue was applied to regions that were culturally very different from 19th/20th century Western Europe.

This is especially pronounced in Eastern Europe. Lacking any catalysts for sweeping change in the 14th century, the Eastern European peasants largely continued upon the original medieval path until the 18th and 19th centuries, when the tsars began to notice that the West had made enormous strides they had not. They responded by forcing the largely illiterate peasant populations under their control to embark upon a Westernization and industrialization campaign. Using methods of coercion and inept central planning that were largely continued by the later Communists, Peter the Great initiated a half-successful attempt to force over five hundred years worth of social change in the space of a few generations. Although this approach eventually (under the Communists) produced a technologically advanced and literate population, it came at the cost of many millions of lives and a cultural legacy that persists to this day.

Peasant Revolts

Peasant, Peasants' or Popular is variously paired with Revolt, Uprising and War and may refer to (sorted chronologically):

Peasant revolt in Flanders 1323-1328

The revolt began as a series of scattered rural riots in late 1323, and peasant insurrection escalated into a full-scale rebellion that dominated public affairs in Flanders for nearly five years until 1328. It was caused by excessive taxations levied by Count Louis I of Flanders, and by his pro-French policies. The insurrection had urban leaders and rural factions which took over most of Flanders by 1325. The king of France directly intervened and the uprising was decisively put down at the Battle of Cassel in August 1328.

English peasants' revolt of 1381

The revolt was precipitated by heavy-handed attempts to enforce the third poll tax, first levied in 1377 supposedly to finance military campaigns overseas — a continuation of the Hundred Years' War initiated by King Edward III of England. The Black Death had greatly reduced the labour force, and as a consequence, the labourers had been able to demand enhanced terms and conditions. The Statute attempted to curb this by pegging wages and restricting the mobility of labour. Probably those labourers employed by lords were effectively exempted, but those labourers working for other employers, both artisans and more substantial peasants, were liable to be fined or held in the stocks. As result, this rebellion had representations from memebers of these classes as well as peasants.

"Wat" Tyler, brought a contingent from Kent in June of 1831 and the 'Men of Essex' had gathered with Jack Straw. The renegade Lollard priest, John Ball, preached a sermon for them that included the famous question that has echoed down the centuries: "When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?"John Ball (priest)#Footnotes|[1]. The rebels were encouraged by this, and crossed London Bridge into the heart of the city the next day and began a systematic attack on certain properties, many of them associated with John of Gaunt and/or the Knights of Hospitaller Order. On June 14, they are reputed to have been met by the young king himself, and to have presented him with a series of demands, including the dismissal of some of his more unpopular ministers and the effective abolition of serfdom.

Meanwhile, a group of rebels stormed the Tower of London— after likely being let in— and summarily executed those hiding there. Richard II of England agreed to reforms such as fair rents, and the abolition of serfdom.

At Smithfield, London, on the following day, further negotiations with the king were arranged, but on this occasion the meeting did not go according to plan. Wat Tyler is is alleged to have behaved belligerently when negotiating with the King, and in the ensuing dispute Tyler was killed. King Richard, seized the opportunity, rode forth and promised the Rebels all was well, that Tyler had been knighted, and their demands would be met - they were to March to St John's Fields, where Wat Tyler would meet them. They did this and were tricked as the Nobles re-established their control, and most of the other leaders of the rebellion were pursued, captured and executed, including John Ball. Jack Straw turned on his associates under torture and betrayed many of them to the executioner - though it did not save him. Following the collapse of the revolt, the king's concessions were quickly revoked, and the tax was levied.

Slovenian peasant revolt of 1515

The Croatian and Slovenian peasant revolt of 1573 was a large peasant revolt in Croatia and what is now Slovenia. The revolt, sparked by cruel treatment of serfs by a local baron, ended after 12 days with the defeat of the rebels and bloody retribution by the nobility.

German peasants war of 1524-1525

The Peasants' War (in German, der Deutsche Bauernkrieg) was a popular revolt in Europe, specifically in the Holy Roman Empire between 1524-1525. It consisted, like the preceding Bundschuh movement and the Hussite Wars, of a mass of economic as well as religious revolts by peasants, townsfolk and nobles. The movement possessed no common programme. The conflict was in the southern, western and central areas, but also affected Switzerland and Austria. There were about 300,000 peasant insurgents: contemporary estimates put the dead at 100,000. The revolt was in many respects a direct consequence of the Protestant reformation, which taught that all people were valued by God and could access God directly without the need of priestly mediation. Some translated this into the political realm, arguing that all people, regardless of social rank, should participate in governance.

Swiss peasant war of 1653

The Old Swiss Confederacy in the 17th century was a federation of thirteen largely independent cantons. The federation comprised rural cantons as well as city states that had expanded their territories into the countryside by political and military means at the cost of the previously ruling liege lords. The cities just took over the preexisting administrative structures. In these city cantons, the city councils ruled the countryside; they held the judicial rights and also appointed the district sheriffs (Landvögte).[1]

Rural and urban cantons had the same standing in the federation. Each canton was sovereign within its territory, pursuing its own foreign politics and also minting its own money. The diet and central council of the federation, the Tagsatzung, held no real power and served more as a coordination instance. The reformation in the early 16th century had led to a confessional division amongst the cantons: the central Swiss cantons including Lucerne had remained Catholic, while Zürich, Berne, Basel, Schaffhausen, and also the city of St. Gallen had become Protestant. The Tagsatzung was often paralysed by disagreements between the equally strong factions of the Catholic and Protestant sides.[2]

Territories that had been conquered since the early 15th century were governed as condominiums by the cantons. Reeves for these territories were assigned by the Tagsatzung for a period of two years; the posts changed bi-annually between the cantons.[3] The Aargau had been annexed in 1415. The western part belonged to Berne, while the eastern part comprised the two condominiums of the former County of Baden in the north and the Freie Ämter ("Free Districts")[b] in the south. The Free Districts had been forcibly recatholized after the Reformation in Switzerland, and the Catholic cantons, especially Lucerne, Zug, and Uri considered these districts part of their sphere of influence and the reeves typically came from these cantons.[4] The Thurgau, which had been annexed in 1460, was also a condominium of the Confederacy.

- 1907 Romanian Peasants' Revolt

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- The Journal of Peasant Studies, 1973 to the present

- Braudel, Fernand, The Structures of Everyday Life vol I of Civilization and Capitalism1992. ISBN-10: 0520081145

- Ladurie, Emmanuel Le Roy, Montaillou : The Promised Land of Error

- Mollat, Michael, The Poor in the Middle Ages, 1986. ISBN: 9780300027891

- Kishlansky, Mark, Civilization in the West, fourth edition, 2001. ISBN-10: 0321070909

- TeBrake, William H. "A Plague of Insurrection: Popular Politics and Peasant Revolt in Flanders, 1323-1328",1993. ISBN 0-8122-3241-0.

External links

- Jerome Blum, Lord and Peasant in Russia From the Ninth to the Nineteenth Century (Princeton University Press, 1961).

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.