Orange Revolution

| Orange Revolution | |||

Orange-clad demonstrators gather in the Independence Square in Kyiv on 22 November 2004. | |||

| Date | 22 November 2004 – 23 January 2005 (Template:Age in years, months, weeks and days) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Caused by | *Kuchmagate crisis severely undermined the legitimacy of President Kuchma and "his candidate" and Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovych[1]

| ||

| Goals | *Annulment of results of the second round of the 2004 presidential elections[2]

| ||

| Methods | Demonstrations, civil disobedience, civil resistance, strike actions | ||

| Resulted in | *Revote ordered by the Supreme Court of Ukraine

| ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| Lead figures | |||

| |||

| Numbers | |||

| Casualties and Losses | |||

| Death(s) | 1 man died from a heart attack | ||

The Orange Revolution (Ukrainian: Помаранчева революція) was a series of protests and political events that took place in Ukraine from late November 2004 to January 2005 in the immediate aftermath of the run-off vote of the 2004 Ukrainian presidential election. Claims of massive corruption, voter intimidation and electoral fraud were alleged. Kyiv, the Ukrainian capital, was the focal point of the movement's campaign of civil resistance, with thousands of protesters demonstrating daily. The revolution was highlighted by a series of nationwide acts of civil disobedience, sit-ins, and general strikes organized by the opposition movement.

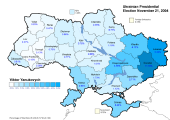

The protests were prompted by reports from several domestic and foreign election monitors as well as the widespread public perception that the results of the run-off vote of November 21, 2004 between leading candidates Viktor Yushchenko and Viktor Yanukovych were rigged by the authorities in favor of the latter. The nationwide protests succeeded when the results of the original run-off were annulled, and a revote was ordered by Ukraine's Supreme Court for 26 December 2004. Under intense scrutiny by domestic and international observers, the second run-off was declared to be "free and fair." The final results showed a clear victory for Yushchenko, who received about 52% of the vote, compared to Yanukovych's 45%. Yushchenko was declared the official winner and with his inauguration on January 23, 2005 in Kyiv, the Orange Revolution ended.

Background

Gongadze assassination or Kuchmagate crisis

Georgiy Gongadze, a Ukrainian journalist and the founder of Ukrayinska Pravda (an Internet newspaper well known for publicizing the corruption or unethical conduct of Ukrainian politicians) was kidnapped and murdered in 2000. Persistent rumors suggested that Ukrainian President Kuchma ordered the killing. Gen. Oleksiy Pukach, a former police officer, was accused of the murder under the orders of a former minister who committed suicide in 2005. Pukach was arrested in 2010[4] and was sentenced to life in prison in 2013.[5] This murder sparked a movement against Kuchma in 2000 that can be seen as the origin of the Orange Revolution in 2004. After two terms of presidency (1994-2005) and the Cassette Scandal of 2000 that ruined his image irreparably, Kuchma decided not to run for a third term in the 2004 elections and instead supported Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovych in the presidential race against Viktor Yushchenko of the Our Ukraine–People's Self-Defense Bloc.

Causes of the Orange Revolution

The state of Ukraine during the 2004 presidential election is considered an "ideal condition" for an outburst from the public. During this time Ukrainians were impatient while waiting for the economic and political transformation.[6] The results of the election were thought to be fraudulent.

Factors enabling the Orange Revolution

The Ukrainian regime that was in power before the Orange Revolution created a path for a democratic society to emerge. It was based on a "competitive authoritarian regime" that is considered a "hybrid regime", allowing for a democracy and market economy to come to life. The election fraud emphasised the Ukrainian citizens' desire for a more pluralistic type of government.

The Cassette Scandal sparked the public's desire to create a social reform movement. It not only undermined the peoples' respect for Kuchma as a president, but also for the elite ruling class in general. Because of Kuchma's scandalous behaviour, he lost many of his supporters with high ranking government positions. Many of the government officials who were on his side went on to fully support the election campaign of Yushchenko as well as his ideas in general.

After a clear lack of faith in the government had been instilled in the Ukrainian population, Yushchenko's role had never been more important to the revolution. Yushchenko was a charismatic candidate who showed no signs of being corrupt. Yuschenko was on the same level as his constituents and presented his ideas in a "non-Soviet" way. Young Ukrainian voters were extremely important to the outcome of the 2004 Presidential election. This new wave of younger people had different views of the main figures in Ukraine. They were exposed to a lot of negativity from the Kuchmagate and therefore had very skewed visions about Kuchma and his ability to lead their country.

The abundance of younger people who participated showed an increasing sense of nationalism that was developing in the country. The Orange Revolution had enough popular impact that it interested people of all ages.[7]

Prelude to the Orange Revolution

Political alliances

In late 2002, Viktor Yushchenko (Our Ukraine), Oleksandr Moroz (Socialist Party of Ukraine), Petro Symonenko (Communist Party of Ukraine) and Yulia Tymoshenko (Yulia Tymoshenko Bloc) issued a joint statement concerning "the beginning of a state revolution in Ukraine." The communists left the alliance. Symonenko opposed the idea of a single candidate from the alliance in the Ukrainian presidential election of 2004; but the other three parties remained allied[9] until July 2006.[10] (In the autumn of 2001 both Tymoshenko and Yushchenko had broached the idea of setting up such a coalition.

On July 2, 2004 Our Ukraine and the Yulia Tymoshenko Bloc established the Force of the People, a coalition which aimed to stop "the destructive process that has, as a result of the incumbent authorities, become a characteristic for Ukraine" - President Leonid Kuchma and Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovych were the "incumbent authorities" that she referenced. The pact included a promise by Viktor Yushchenko to nominate Tymoshenko as Prime Minister if Yushchenko won the October 2004 presidential election.[11]

2004 Ukraine presidential election campaign

The 2004 presidential election in Ukraine eventually featured two main candidates:

- sitting Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovych, largely supported by Leonid Kuchma (the outgoing President of Ukraine who had already served two terms in office from 1994 and was precluded from running himself due to constitutional term limits)

- the opposition candidate Viktor Yushchenko, leader of the Our Ukraine faction in the Ukrainian parliament and a former Prime Minister (1999–2001)

The election took place in a highly charged atmosphere, with the Yanukovych team and the outgoing president's administration using their control of the government and state apparatus for intimidation of Yushchenko and his supporters. In September 2004 Yushchenko suffered dioxin poisoning under mysterious circumstances. While he survived and returned to the campaign trail, the poisoning undermined his health and altered his appearance dramatically (his face remains disfigured by the consequences).

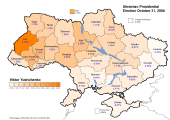

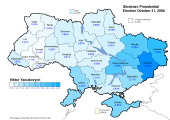

The two main candidates were neck and neck in the first-round vote held on October 31, 2004, with Yanulovych winning 39.32% and Yushchenko gaining 39.87% of the votes cast. The candidates who came third and fourth collected much less: Oleksandr Moroz of the Socialist Party of Ukraine and Petro Symonenko of the Communist Party of Ukraine received 5.82% and 4.97%, respectively. Since no candidate had won more than 50% of the cast ballots, Ukrainian law mandated a run-off vote between two leading candidates. After the announcement of the run-off, Oleksandr Moroz threw his support behind Viktor Yushchenko. The Progressive Socialist Party's Natalia Vitrenko, who won 1.53% of the vote, endorsed Yanukovych, who hoped for Petro Simonenko's endorsement but did not receive it.

In the wake of the first round of the election, many complaints emerged regarding voting irregularities in favor of the government-supported Yanukovych. However, as it was clear that neither nominee was close enough to collecting an outright majority in the first round, challenging the initial result would not have affected the outcome of the round. So the complaints were not actively pursued and both candidates concentrated on the upcoming run-off scheduled for November 21.

Pora! activists were arrested in October 2004, but the release of many (reportedly on President Kuchma's personal order) gave growing confidence to the opposition.[12]

Yushchenko's supporters originally adopted orange as the signifying color of his election campaign. Later, the color gave its name to an entire series of political labels, such as the Oranges (Pomaranchevi in Ukrainian) for his political camp and its supporters. At the time when the mass protests grew, and especially when they brought about political change in the country, the term Orange Revolution came to represent the entire series of events.

In view of the success of using color as a symbol to mobilize supporters, the Yanukovych camp chose blue for themselves.

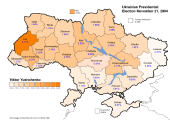

Protests

Template:History of Ukraine Protests began on the eve of the second round of voting, as the official count differed markedly from exit poll results which gave Yushchenko up to an 11% lead, while official results gave the election win to Yanukovych by 3%. While Yanukovych supporters have claimed that Yushchenko's connections to the Ukrainian media explain this disparity, the Yushchenko team publicized evidence of many incidents of electoral fraud in favor of the government-backed Yanukovych, witnessed by many local and foreign observers.[13] These accusations were reinforced by similar allegations, though at a lesser scale, during the first presidential run of October.[14][15]

The Yushchenko campaign publicly called for protest on the dawn of election day, November 21, 2004, when allegations of fraud began to spread in the form of leaflets printed and distributed by the 'Democratic Initiatives' foundation, announcing on the basis of its exit poll that Yushchenko had won. Beginning on November 22, 2004, massive protests[nb 1] In 2016 the Russian newspaper Izvestia claimed, "in Central Asia weak regimes are already being attacked by extremists and 'Orange Revolutions'."{{#tag:ref|Writing about the 2016 US presidential election Izvestia claimed "If the war-like, Russia-hating Hillary Clinton wins the US election, a third front could open up in the Caucasus; money will pour in to support terrorists, just like it did during the two Chechen wars. There could even be a fourth front in Central Asia, where weak regimes are already being attacked by extremists and 'Orange [66]

In Russian nationalist circles the Orange Revolution has been linked with fascism because, albeit marginal, Ukrainian nationalist extreme right-wing groups and Ukrainian Americans (including Viktor Yushchenko's wife, Kateryna Yushchenko, who was born in the United States) were involved in the demonstrations; Russian nationalist groups see both as branches of the same tree of fascism. The involvement of Ukrainian Americans lead them to believe the Orange Revolution was steered by the CIA.[67]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Abel Polese and Donnacha Ó Beacháin, "The Colour Revolutions in the Former Soviet Republics: Ukraine," by Nathaniel Copsey, Routledge Contemporary Russia and Eastern Europe Series, 30-44. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ↑ "Ukraine profile," BBC News, March 1, 2022. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ↑ "Ukrainian Politics, Energy and Corruption under Kuchma and Yushchenko," Harvard University, March 7, 2008. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ↑ "Georgiy Gongadze murder tied to late Ukrainian minister," BBC News, September 14, 2010. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ↑ Roy Greenslade, "Ukrainian policeman gets life for murder of journalist," The Guardian, January 30, 2013. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ↑ Taras Kuzio, "Ukraine's Orange Revolution: Causes and Consequences," University of Ottawa, April 28, 2005.

- ↑ Joanna Konieczna, "The Orange Revolution in Ukraine. An Attempt to Understand the Reasons," Centre for Eastern Studies;;, July 13, 2005. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ↑ Wojciech Stanistawski, "The Orange Ribbon: A Calendar of the Political Crisis in Ukraine," Centre for Eastern Studies, Warsaw, Autumn 2004.

- ↑ Paul J. D'Anieri, Understanding Ukrainian Politics: Power, Politics, and Institutional Design (London, UK: Routledge, 2006, ISBN 978-0765618115), 117.

- ↑ "Ukraine coalition born in chaos," BBC News, July 11, 2006. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ↑ Anders Aslund and Michael A. McFaul, Revolution in Orange: The Origins of Ukraine's Democratic Breakthrough (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2006, ISBN 978-0870032219)

- ↑ Adam Roberts and Timothy Garton Ash, eds., Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Non-violent Action from Gandhi to the Present (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0199552016), 345.

- ↑ Paul Quinn-Judge, Yuri Zarakhovich, "The Orange Revolution," Time, November 28, 2004. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ↑ Andrew Wilson, "Ukraine's 'Orange Revolution' of 2004: The Paradoxes of Negotiation", in Adam Roberts and Timothy Garton Ash (eds.), Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Non-violent Action from Gandhi to the Present (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0199552016), 295–316.

- ↑ Adrian Karatnycky, "Ukraine's Orange Revolution," Foreign Affairs, March-April 2005.

- ↑ "Timeline: Battle for Ukraine," January 23, 2005. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ↑ Veronica Khokhlova, "New Kids On the Bloc," The New York Times, November 26, 2004. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ Kamil Tchorek, "Protest grows in western city," The Times, November 26, 2004. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Yushchenko takes reins in Ukraine," BBC NEWS, January 23, 2005. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ↑ USAID Report "Democracy Rising," (PDF) USAID, September 2005. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Supreme Court of Ukraine decision regarding the annulment of 21 November vote," Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Yanukovych says presidential election scenario of 2004 won't be repeated in 2010," Interfax-Ukraine, November 27, 2009. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Results of Voting in Ukraine Presidential Elections 2004", Central Election Commission of Ukraine. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ Timeline: Battle for Ukraine

- ↑ "Official CEC announcement of results as of 10 January 2005," Central Election Commission, March 12, 2005. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ Peter Finn, "In a Final Triumph, Ukrainian Sworn In," Washington Post, January 24, 2005. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ Orest Subtelny, Ukraine: A History 4th Edition (Toronto, CA: University of Toronto Press, 2009, ISBN 1442609915)

- ↑ C. J. Chivers, "BACK CHANNELS: A Crackdown Averted; How Top Spies in Ukraine Changed the Nation's Path," The New York Times, January 17, 2005. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ For question on ultimate source of orders and mobilisation details see Lehrke, Jesse Paul. The Transition to National Armies in the Former Soviet Republics, 1988–2005. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge (2013), 188–89.

- ↑ "How Yanukovich Forged the Elections. Headquarters’ Telephone Talks Intercepted," Ukrainska Pravda, November 24, 2004. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ Abel Polese, Russia, the US, “the Others” and the “101 Things to Do to Win a (Colour)Revolution”: Reflections on Georgia and Ukraine, Routledge October 26, 2011. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ McFaul, Michael, "Transitions from Postcommunism," Journal of Democracy 16 (3), (2005): 12.

- ↑ Joshua Goldstein, "The Role of Digital Networked Technologies in the Ukrainian Orange Revolution," Berkman Center Research Publication, 2007, 14.

- ↑ Thomas Kalil, Harnessing the Mobile Revolution, The New Policy Institute, 2008, 14.

- ↑ "Update: Return to 1996 Constitution strengthens president, raises legal questions," Kyiv Post, October 1, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Court forbade Maydan after first tour of election," UNIAN, January 134, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Central Election Commission Candidate Results," CEC Ukraine, January 19, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Ukraine. Farewell to the Orange Revolution," EuropaRussia, January 19, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Ukraine election: Yanukovych urges Tymoshenko to quit," BBC News, February 10, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Yanukovych appeals to the nation, asks Tymoshenko to step down," Kyiv Post, February 10, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Akhmetov: Ideals of 'Orange Revolution' won at election in 2010," Kyiv Post, February 26, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Yulia Tymoshenko’s address to the people of Ukraine,", Yulia Tymoshenko official website, February 22, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Day of Freedom: here comes the end to revolutions," ForUm November 23, 2011. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Yanukovych signs decree on new holiday replacing Ukrainian Independence Day," Kyiv Post, December 30, 2011. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Yanukovych abolishes Day of Liberty on 22 November," Observer, December 30, 2011. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Yanukovych cancels Freedom Day on 22 Nov," Z I K, December 31, 2011. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Ukrainians to celebrate Day of Dignity and Freedom on November 21, Unity Day on January 22," | Interfax-Ukraine, November 13, 2014. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ D'Anieri, 63.

- ↑ Andrew Rettman, "EU endorses Ukraine election result," euobserver, February 8, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ World Digest, "International observers say Ukrainian election was free and fair," Washington Post, February 9, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ "European Parliament president greets Ukraine on conducting free and fair presidential election," Kyiv Post, February 9, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ Andrej Lushnycky and Mykola Riabchuk, Ukraine on its meandering path between East and West, (Pieterlin and Bern, SW: Peter Lang Publishers, 2009, ISBN 303911607X), 52.

- ↑ Jan Maksymiuk, "Ukraine:Has Yushchenko Betrayed The Orange Revolution?" Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, September 30, 2005. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ Tammy M. Lynch, "Independent standpoint on Ukraine:Dismissal of Prosecutor-General, Closure of Poroshenko Case Create New," Institute for the Study of Conflict, Ideology & Policy, October 28, 2005. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ Pavel Polityuk and Richard Balmforth, "Yanukovich declared winner in Ukraine poll," The Independent, February 15, 2010. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ↑ "Viktor Yanukovych sworn in as Ukraine president," BBC News, February 25, 2010. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ↑ Julia Lugovska, "The upcoming parliamentary elections in Ukraine [Summary], WSN, October 23, 2012. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Q&A:Ukrainian parliamentary election," BBC News, October 23, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ↑ Taras Kuzio, "BEREZOVSKY HOPES TO SELL ORANGE REVOLUTION TO RUSSIA," Eurasia Daily Monitor 2(54), March 17, 2005. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ Taras Kuzio, "Ukraine is Not Russia:Comparing Youth Political Activism," SAIS Review 26(2), Summer–Fall 2006. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ↑ "Lukashenko Growls at Inauguration," The Moscow Times, January 24, 2011. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ↑ "Putin calls 'color revolutions' an instrument of destabilization," Kyiv Post, December 15, 2011. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ↑ Interfax-Ukraine, "'Orange' methods will fail in South Ossetia," Kyiv Post, December 2, 2011. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Russians Rally as Putin Hints Reforms, Warns of Regime Change," Sputnik International, February 4, 2012. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Putin’s aide calls opinion that all Ukrainians want European integration 'sick self-delusion'," Interfax-Europe, August 21, 2013.

- ↑ "Russian media's love affair with Trump," BBC news, November 2, 2016. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ↑ Andreas Umland, "New Extremely Right-Wing Intellectual Circles in Russia: The Anti-Orange Committee, the Isborsk Club and the Florian Geyer Club," International Relations and Security Network, August 5, 2013. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Further reading

- Paul D'Anieri, ed. Orange Revolution and Aftermath: Mobilisation, Apathy, and the State in Ukraine (Johns Hopkins University Press; 2011) 328 pages

- Tetyana Tiryshkina. The Orange Revolution in Ukraine – a Step to Freedom (2nd ed. 2007)

- Andrew Wilson (March 2006). Ukraine's Orange Revolution. Yale University Press. Template:ISBN.

- Anders Åslund and Michael McFaul (January 2006). Revolution in Orange: The Origins of Ukraine's Democratic Breakthrough. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Template:ISBN.

- Askold Krushelnycky (2006). An Orange Revolution: A Personal Journey Through Ukrainian History. Template:ISBN.

- Pavol Demes and Joerg Forbrig (eds.). Reclaiming Democracy: Civil Society and Electoral Change in Central and Eastern Europe. German Marshall Fund, 2007.

- Lehrke, Jesse Paul. "The Transition to National Armies in the Former Soviet Republics, 1988–2005." Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge (2013). Especially p. 185-199 but also p. 152-159 for background. (See: http://www.routledge.com/books/details/9780415688369/ {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}}).

- Andrey Kolesnikov (2005). Первый Украинский: записки с передовой (First Ukrainian [Front]: Notes from the Front Line). Moscow: Vagrius. Template:ISBN. {{#invoke:lang/utilities|in_lang|template=in lang}}

- Giuseppe D'Amato, EuroSogno e i nuovi Muri ad Est {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}} (The Euro-Dream and the new Walls to the East). L'Unione europea e la dimensione orientale. Greco-Greco editore, Milano, 2008. pp. 133–151. (Italian).

- The Orange Ribbon: A Calendar of the Political Crisis in Ukraine, compiled by Wojciech Stanistawski. Warsaw: Centre for Eastern Studies (www.osw.waw.pl), 2005. by the Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW), Warsaw, 2005.

- US campaign behind the turmoil in Kiev {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}}, The Guardian, 2, 6 November 2004.

- Six questions to the critics of Ukraine's orange revolution {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}}, The Guardian, 2 December 2004.

- The Orange Revolution, TIME.com, Monday, 6 December 2004 (excerpt, requires subscription)

- The price of People Power {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}}, The Guardian, 7 December 2004.

- U.S. Money has Helped Opposition in Ukraine {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}}, Associated Press, 11 December 2004.

External links

Template:Commons category multi

- Orange Winter, a feature documentary about the Orange revolution by Andrei Zagdansky

- "Role of Internet-based Information Flows and Technologies in Electoral Revolutions:The Case of Ukraine’s Orange Revolution", Lysenko, V.V., and Desouza, K.C., First Monday, 15 (9), 2010

- [1] The Economic Policy of Ukraine after the Orange Revolution by Anders Åslund

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Cite error: <ref> tags exist for a group named "nb", but no corresponding <references group="nb"/> tag was found