Larsen, Nella

Joshua Sapad (talk | contribs) |

Joshua Sapad (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

===Later work=== | ===Later work=== | ||

| − | In 1930, Larsen published "Sanctuary" [http://www.nku.edu/~diesmanj/sanctuary.html], a short story for which she was | + | In 1930, Larsen published "Sanctuary" [http://www.nku.edu/~diesmanj/sanctuary.html], a short story for which she suffered from controversy and accusations of plagiarism. A reader saw a resemblance in "Sanctuary" to [[Sheila Kaye-Smith]]'s "Mrs. Adis". Kaye-Smith was an English writer, mainly on rural themes, and very popular in the United States. "Sanctuary"’s basic plot, and a little of the descriptions and dialogue were virtually identical. Compared to Kaye-Smith’s tale, "Sanctuary" was longer, better written and more explicitly political, specifically around issues of race, rather than class as in "Mrs Adis." Larsen reworked and updated the tale into a modern American black context. Much later Sheila Kaye-Smith herself wrote in "All the Books of My Life" (Cassell, London, 1956) that she had in fact based "Mrs Adis" on an old story by [[St Francis de Sales]]. It is unknown whether she ever knew of the Larsen controversy. Larsen was able to exonerate herself, with confirmation from editors who had viewed early drafts of the story. |

| − | + | Despite having cleared her name, Larsen lost some confidence in her writing during the ordeal and due to the breakup of her marriage, and she found her subsequent travels in Europe, under a prestigious [[Guggenheim Fellowship]], to be fruitless. She spent time in [[Mallorca]] and [[Paris]] working on a novel about a love triangle among the three white protagonists; the book was never published. Upon returning from Europe, she initially remained committed to her craft, but did not publish any work. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Later life== | ==Later life== | ||

| − | + | Larsen returned to New York in 1933 after her divorce to Imes was complete. She lived on [[alimony]] until her ex-husband's death in 1942; by then she had stopped writing, apparently depressed, and was suspected to have been using drugs. In order to support herself, she returned to working as a nurse and disappeared from the literary circles in which she previously thrived. She lived on the Lower East Side, and did not venture to Harlem. | |

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

Revision as of 07:15, 23 December 2007

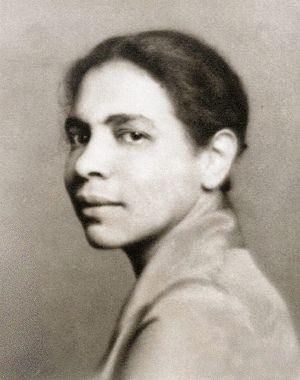

Nellallitea 'Nella' Larsen (April 13, 1891 – March 30, 1964) was a mixed-race novelist of the Harlem Renaissance, an era marked by a creative flourish among African-American artists in Harlem. As a writer, Larsen showed early promise, but she only published two novels, as well as a few short stories. Though her literary output was scant, critical consensus is that what she wrote was of extraordinary quality, and her work earned her recognition by her contemporaries and by present day scholars.

Early life

Nella Larsen was born “Nellie Walker in Chicago on April 13, 1891. Her mother, Marie Hanson, was a Danish immigrant domestic case worker. Her father, Peter Walker, was a black West Indian from Saint Croix. Her father soon disappeared from the picture and her mother married Peter Larsen, whose surname Nella adopted. Her stepfather and her mother also had a daughter, Nella’s half-sister.

As a child, Larsen experienced struggles as the lone mixed-race member of the household. As the racial lines in Chicago became more and more rigid, the family found it difficult finding racially-accepting neighborhoods. Later, Larsen left Chicago and lived several years with her mother's relatives in Denmark. In 1907-08, she briefly attended Fisk University, in Nashville, Tennessee, a historically Black University, which at that time had an entirely Black student body. Biographer George Hutchinson speculates that she was expelled for some violation of Fisk's very strict dress or conduct codes. In 1910 she returned to Denmark, auditing courses at the University of Copenhagen for two years.

By 1912, Larsen moved to New York City, and she studied nursing at Lincoln Hospital. Upon graduating in 1915, she went South to work at the Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama where she became head nurse at a hospital and training school. While in Tuskegee, she came in contact with Booker T. Washington's model of education and became disillusioned with it. (Washington died shortly after Larsen arrived in Tuskeegee.) Working conditions for nurses were poor—their duties included doing hospital laundry—and Larsen was left exhausted, prompting her to resign 1916, at and return to New York to work again as a nurse. However, after working as a nurse through the Spanish flu pandemic, she left nursing and became a librarian.

In 1919, she married Elmer Samuel Imes, a prominent physicist, the second African American to receive a Ph.D in physics. They moved to Harlem, where Larsen took a job at the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library (NYPL). In the year after her marriage, she began to write, publishing her first pieces in 1920.

Literary career

Certified in 1923 by the NYPL's library school, she transferred to a children's librarian's position in Manhattan's Lower East Side. Her marriage to Imes ensured her company with Harlem's black elite, and she became acquainted with Walter White, W.E.B. Du Bois, and James Weldon Johnson of the NAACP. In 1926, having made friends with important figures in the Negro Awakening that became the Harlem Renaissance, Larsen gave up her work as a librarian and began to work as a writer active in the literary community, her first story printed in January of that year.

Quicksand

In 1928, at the urging of Walter White, Larsen wrote her first novel, Quicksand, a largely autobiographical novel. A first draft was written over a brief period, and was first published on March 20, 1928, receiving significant critical acclaim, if not great financial success.

Nella Larsen's first novel tells the story of bi-racial Helga Crane, a fictional character clearly based on Larsen herself. Crane is the daughter of a Danish mother and a black father, who goes to various places and communities in search of somewhere she feels comfortable and at peace. Her travels bring her in contact with many of the communities Larsen herself knew. She begins in "Naxos," a Southern Negro school based on Tuskegee University, where she finds herself unsatisfied with the complacency of those around her, mentioning a sermon by a white preacher telling them that their segregation of themselves into black schools was good sense, and that to strive for equality would be them becoming avaricious. In her travels, Helga finds herself in Chicago, where her white relatives shun her. In Harlem, she finds a refined but often hypocritical black middle class obsessed with the "race problem." In Copenhagen, she is treated as a highly desirable racial exotic; and finally the poor deep South, where she is disillusioned by people's blind adherence to religion. In each of these searches, Helga fails to find fulfillment.

To complement her struggle with her own racial identity and its manifestation as the constant disappointments of the external social world, Helga also struggles in love. Larsen chronicles Helga's search for a marriage partner; the novel opens with her engaged to a prestigious Southern Negro man she does not really love, sees her turn down the proposal of a famous European artist, and ends with her seducing and marrying a Southern preacher. The novel's close is deeply pessimistic as Helga sees what began as sexual fulfillment turn into an endless chain of pregnancies and suffering. Larsen's bleak ending to the novel has Helga ultimately damned by her inability to reconcile the social conundrum of her mixed-race identity with her own personal ambitions.

Passing

In 1929, Larsen published Passing, her second novel, a story of two light-skinned women, childhood friends Irene Redfield and Clare Kendry. Both women are of mixed heritage and are light enough to pass as white. Irene becomes the socialite wife of a prominent doctor in New York City. Clare fully commits herself to passing and avoids a life of toil by marrying John Bellew, a racist white man who calls her "Nig," with affection, not knowing her true heritage. He derives the nickname from the fact that, as she's gotten older, to his eyes her skin has slightly darkened. The novel centers on the meeting of the two childhood friends later in life, the different circumstances of their "passing," and the unfolding of events as each woman is seduced by the other's daring lifestyle. In Passing, Larsen traces a tragic path as Irene becomes paranoid that her husband is having an affair with Clare, though the reader is never told whether her fears are justified or not, and numerous cues point in both directions. At the novel's famously ambiguous end, Clare's race is revealed to John Bellew, and Clare "falls" out a high window to her sudden death. Critical debate ponders both the possibility that Irene pushed Clare out the window and the possibility that Clare willingly jumped on her own accord.

Many see this novel as an example of the plot of the tragic mulatto, a common figure in early African American literature. Others suggest that the novel complicates that plot by introducing the dual figures of Irene and Clare, who in many ways mirror and complicate each other. The novel also suggests erotic undertones in the two women's relationship, and some read the novel as one of repressed lesbian desire.

Recently, Passing has received a great deal of attention because of its close attention to racial and sexual ambiguities and to liminal spaces. It has now achieved canonical status in many American universities.

Later work

In 1930, Larsen published "Sanctuary" [1], a short story for which she suffered from controversy and accusations of plagiarism. A reader saw a resemblance in "Sanctuary" to Sheila Kaye-Smith's "Mrs. Adis". Kaye-Smith was an English writer, mainly on rural themes, and very popular in the United States. "Sanctuary"’s basic plot, and a little of the descriptions and dialogue were virtually identical. Compared to Kaye-Smith’s tale, "Sanctuary" was longer, better written and more explicitly political, specifically around issues of race, rather than class as in "Mrs Adis." Larsen reworked and updated the tale into a modern American black context. Much later Sheila Kaye-Smith herself wrote in "All the Books of My Life" (Cassell, London, 1956) that she had in fact based "Mrs Adis" on an old story by St Francis de Sales. It is unknown whether she ever knew of the Larsen controversy. Larsen was able to exonerate herself, with confirmation from editors who had viewed early drafts of the story.

Despite having cleared her name, Larsen lost some confidence in her writing during the ordeal and due to the breakup of her marriage, and she found her subsequent travels in Europe, under a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship, to be fruitless. She spent time in Mallorca and Paris working on a novel about a love triangle among the three white protagonists; the book was never published. Upon returning from Europe, she initially remained committed to her craft, but did not publish any work.

Later life

Larsen returned to New York in 1933 after her divorce to Imes was complete. She lived on alimony until her ex-husband's death in 1942; by then she had stopped writing, apparently depressed, and was suspected to have been using drugs. In order to support herself, she returned to working as a nurse and disappeared from the literary circles in which she previously thrived. She lived on the Lower East Side, and did not venture to Harlem.

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Thadious M. Davis, Nella Larsen, Novelist of the Harlem Renaissance: A Woman's Life Unveiled. ISBN 0-8071-2070-7.

- Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 51: Afro-American Writers from the Harlem Renaissance to 1940. A Bruccoli Clark Layman Book. Edited by Trudier Harris, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The Gale Group, 1987. pp. 182-192.

- George Hutchinson. In Search of Nella Larsen: A Biography of the Color Line. Belknap Press, 2006. ISBN 0674021800.

- Sheila Kaye-Smith, All the Books of My Life, Cassell, London, 1956.

External Links

- Pinckney, Darryl. "Shadows". The Nation, July 17/24, 2006, p.26–30. A review of Hutchinson's In Search of Nella Larsen: A Biography of the Color Line. Retrieved December 21, 2007.

- Sullivan, Neil. "Nella Larsen's 'Passing' and the Fading Subject". Article from African American Review. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- Nella Larsen. Voices From the Gaps. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- Nella Larsen. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- Nella Larsen: links, secondary bibliography. Retrieved October 14, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.