al-Khwārizmī, Muhammad ibn Mūsā

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (29 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

| − | {{epname}} | + | {{epname|al-Khwārizmī, Muhammad ibn Mūsā}} |

{{Infobox Biography | {{Infobox Biography | ||

| subject_name = Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī | | subject_name = Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī | ||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | + | '''{{transl|ar|ALA|Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī}}''' ({{lang-ar|محمد بن موسى الخوارزمي}}) was a [[Persian people|Persian]] [[Islamic mathematics|mathematician]], [[Islamic astronomy|astronomer]], [[Islamic astrology|astrologer]] and [[geographer]]. He was born around 780 in [[Khwarezm|Khwārizm]] (now [[Khiva]], [[Uzbekistan]]) and died around 850. He worked most of his life as a [[scholar]] in the [[House of Wisdom]] in [[Baghdad]]. | |

| − | + | His ''[[The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing|Algebra]]'' was the first book on the systematic solution of [[linear equation|linear]] and [[quadratic equation]]s. Consequently he is considered to be the father of [[algebra]],<ref>Solomon Gandz, "The Sources of al-Khowārizmī's Algebra" Osiris 1 (1936): 263–277.</ref> a title he shares with [[Diophantus]]. [[Latin]] translations of his ''Arithmetic'', on the [[Indian numerals]], introduced the [[decimal]] [[Positional notation|positional number system]] to the [[Western world]] in the twelfth century.<ref>Dirk Jan Struik, ''A Concise History of Mathematics'' (Dover Publications, 1987, ISBN 0486602559), 93.</ref> He revised and updated [[Ptolemy]]'s ''Geography'' as well as writing several works on astronomy and astrology. | |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | + | His contributions not only made a great impact on mathematics, but on language as well. The word algebra is derived from ''al-jabr'', one of the two operations used to solve [[quadratic equations]], as described in his book. The words ''[[algorism]]'' and ''[[algorithm]]'' stem from ''algoritmi'', the [[Latinization]] of his name.<ref>Abdullah al-Daffa', ''The Muslim contribution to mathematics'' (London, Croom Helm, 1977, ISBN 0856644641).</ref> His name is also the origin of the [[Spanish language|Spanish]] word ''guarismo''<ref>Donald E. Knuth, ''Algorithms in Modern Mathematics and Computer Science'' (Springer-Verlag, 1979, ISBN 0387111573).</ref> and of the [[Portuguese language|Portuguese]] word ''algarismo'', both meaning "[[digit]]." | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | His ''[[The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing|Algebra]]'' was the first book on the systematic solution of [[linear]] and [[quadratic]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | His contributions not only made a great impact on mathematics, but on language as well. The word | ||

=== Biography === | === Biography === | ||

| + | Few details about al-Khwārizmī's life are known; it is not even certain exactly where he was born. His name indicates he might have come from [[Khwarizm]] (Khiva) in the [[Khorasan]] province of the [[Abbasid]] empire (now [[Xorazm Province]] of [[Uzbekistan]]). | ||

| − | + | His [[Kunya (Arabic)|kunya]] is given as either ''{{Unicode|Abū ʿAbd Allāh}}'' (Arabic: {{lang|ar|أبو عبد الله}}) or ''{{Unicode|Abū Jaʿfar}}''.<ref>possibly because it is mistaken with that of {{unicode|[[Muhammad bin Musa|Ǧaʿfar Muḥammad ibn Mūsā ibn Šākir]]}}. M. Dunlop. ''{{unicode|Muḥammad b. Mūsā al-Khwārizmī}}''. JRAS 1943, 248-250).</ref> | |

| − | + | With his full name of Abu Ja’far Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, historians are able to extract that he was the son of Moses, the father of Ja’far. Either he or his ancestors came from Khiva (then Khwarazm), which is a city south of the Aral Sea in central Asia. That this city lies between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers remains under discussion. | |

The [[historian]] [[al-Tabari]] gave his name as Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwārizmī al-Majousi al-Katarbali (Arabic: {{lang|ar|محمد بن موسى الخوارزميّ المجوسيّ القطربّليّ}}). The [[epithet]] ''al-Qutrubbulli'' indicates he might instead have came from [[Qutrubbull]], a small town near [[Baghdad]]. Regarding al-Khwārizmī's religion, Toomer writes: | The [[historian]] [[al-Tabari]] gave his name as Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwārizmī al-Majousi al-Katarbali (Arabic: {{lang|ar|محمد بن موسى الخوارزميّ المجوسيّ القطربّليّ}}). The [[epithet]] ''al-Qutrubbulli'' indicates he might instead have came from [[Qutrubbull]], a small town near [[Baghdad]]. Regarding al-Khwārizmī's religion, Toomer writes: | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| − | Another epithet given to him by al-Ṭabarī, "al-Majūsī," would seem to indicate that he was an adherent of the old Zoroastrian religion. This would still have been possible at that time for a man of Iranian origin, but the pious preface to al-Khwārizmī's ''Algebra'' shows that he was an orthodox [[Muslim]], so al-Ṭabarī's epithet could mean no more than that his forebears, and perhaps he in his youth, had been a Zoroastrian.<ref>Toomer</ref> | + | Another epithet given to him by al-Ṭabarī, "al-Majūsī," would seem to indicate that he was an adherent of the old Zoroastrian religion. This would still have been possible at that time for a man of Iranian origin, but the pious preface to al-Khwārizmī's ''Algebra'' shows that he was an orthodox [[Muslim]], so al-Ṭabarī's epithet could mean no more than that his forebears, and perhaps he in his youth, had been a Zoroastrian.<ref>Gerald Toomer, "Al-Khwārizmī, Abu Jaʿfar Muḥammad ibn Mūsā" Charles Coulston Gillispie (ed.), ''Dictionary of Scientific Biography Volume 7'' (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1970–1990), 358–365.</ref> |

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

| − | + | Al-Khwārizmī accomplished most of his work in the period between 813 and 833. After the [[Islamic conquest of Persia]], Baghdad became the centre of scientific studies and trade, and many merchants and scientists, from as far as [[China]] and [[India]], traveled to this city—and apparently, so did Al-Khwārizmī. He worked in Baghdad as a scholar at the [[House of Wisdom]] established by [[Caliph]] {{unicode|[[al-Maʾmūn]]}}, where he studied the sciences and mathematics, which included the translation of [[Greek]] and [[Sanskrit]] scientific manuscripts. | |

| + | |||

| + | In ''Scientists of The Ancient World'', Margaret J. Anderson states: | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | When al-Khwarizmi lived in Baghdad it was quite a new city, but its location at the meeting place of trade routes from India, Persia, and ports on the Mediterranean Sea had caused it to grow rapidly. From 813 to 823, Baghdad was ruled by the caliph (spiritual and political leader) al-Ma’mun. The caliph, who himself was an enthusiastic scholar and philosopher, soon turned the city into an important intellectual center. He established the House of Wisdom and ordered his scholars to translate the classical Greek texts into Arabic. Copies of these books ended up in Muslim centers of learning in Spain and Sicily. Later, they were translated into Latin and passed on to universities throughout Europe. | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

== Contributions == | == Contributions == | ||

| − | |||

[[Image:The Algebra of Mohammed ben Musa (frontispiece).png|thumb|right|The [[frontispiece]] of Frederic Rosen's ''The Algebra of Mohammed ben Musa'' (1831)]] | [[Image:The Algebra of Mohammed ben Musa (frontispiece).png|thumb|right|The [[frontispiece]] of Frederic Rosen's ''The Algebra of Mohammed ben Musa'' (1831)]] | ||

His major contributions to [[mathematics]], [[astronomy]], [[astrology]], [[geography]] and [[cartography]] provided foundations for later and even more widespread innovation in [[Algebra]], [[trigonometry]], and his other areas of interest. His systematic and logical approach to solving [[linear]] and [[quadratic]] equations gave shape to the discipline of ''Algebra'', a word that is derived from the name of his 830 book on the subject, ''al-Kitab al-mukhtasar fi hisab al-jabr wa'l-muqabala'' ([[Arabic]] الكتاب المختصر في حساب الجبر والمقابلة) or: "The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing." The book was first translated into Latin in the twelfth century. | His major contributions to [[mathematics]], [[astronomy]], [[astrology]], [[geography]] and [[cartography]] provided foundations for later and even more widespread innovation in [[Algebra]], [[trigonometry]], and his other areas of interest. His systematic and logical approach to solving [[linear]] and [[quadratic]] equations gave shape to the discipline of ''Algebra'', a word that is derived from the name of his 830 book on the subject, ''al-Kitab al-mukhtasar fi hisab al-jabr wa'l-muqabala'' ([[Arabic]] الكتاب المختصر في حساب الجبر والمقابلة) or: "The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing." The book was first translated into Latin in the twelfth century. | ||

| Line 50: | Line 47: | ||

Al-Khwārizmī systematized and corrected [[Ptolemy]]'s data in [[geography]] with regards to [[Africa]] and the [[Middle East]]. Another major book was his ''Kitab surat al-ard'' ("The Image of the Earth"; translated as Geography), which presented the coordinates of localities in the known world based, ultimately, on those in the Geography of Ptolemy but with improved values for the length of the [[Mediterranean Sea]] and the location of cities in Asia and Africa. | Al-Khwārizmī systematized and corrected [[Ptolemy]]'s data in [[geography]] with regards to [[Africa]] and the [[Middle East]]. Another major book was his ''Kitab surat al-ard'' ("The Image of the Earth"; translated as Geography), which presented the coordinates of localities in the known world based, ultimately, on those in the Geography of Ptolemy but with improved values for the length of the [[Mediterranean Sea]] and the location of cities in Asia and Africa. | ||

| − | He also assisted in the construction of a world map for the caliph [[al-Ma'mun]] and participated in a project to determine the circumference of the Earth, supervising the work of 70 geographers to create the [[map]] of the then "known world". | + | He also assisted in the construction of a world map for the caliph [[al-Ma'mun]] and participated in a project to determine the circumference of the Earth, supervising the work of 70 geographers to create the [[map]] of the then "known world". |

| − | When his work was copied and transferred to [[Europe]] through [[Latin]] translations, it had a profound impact on the advancement of basic mathematics in Europe. He also wrote on mechanical devices like the <!-- [[clock]], al-Biruni? —>[[astrolabe]] and [[sundial]]. | + | When his work was copied and transferred to [[Europe]] through [[Latin]] translations, it had a profound impact on the advancement of basic mathematics in Europe. He also wrote on mechanical devices like the <!-- [[clock]], al-Biruni? —>[[astrolabe]] and [[sundial]]. |

=== Algebra === | === Algebra === | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

''{{Unicode|al-Kitāb al-mukhtaṣar fī ḥisāb al-jabr wa-l-muqābala}}'' (Arabic: الكتاب المختصر في حساب الجبر والمقابلة “The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion <!-- <small>(variants: Restoring, Reuniting)</small> —>and Balancing”) is a [[mathematical]] book written approximately 830 C.E. | ''{{Unicode|al-Kitāb al-mukhtaṣar fī ḥisāb al-jabr wa-l-muqābala}}'' (Arabic: الكتاب المختصر في حساب الجبر والمقابلة “The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion <!-- <small>(variants: Restoring, Reuniting)</small> —>and Balancing”) is a [[mathematical]] book written approximately 830 C.E. | ||

| − | The book is considered to have defined [[Algebra]]. The word ''Algebra'' is derived from the name of one of the basic operations with equations (''al-jabr'') described in this book. The book was translated in Latin as ''Liber Algebrae et Almucabala'' by | + | The book is considered to have defined [[Algebra]]. The word ''Algebra'' is derived from the name of one of the basic operations with equations (''al-jabr'') described in this book. The book was translated in Latin as ''Liber Algebrae et Almucabala'' by Robert of Chester (Segovia, 1145)<ref>mactutor-hanasi</ref> hence "Algebra," and also by [[Gerard of Cremona]]. A unique Arabic copy is kept at Oxford and was translated in 1831 by F. Rosen. A Latin translation is kept is Cambridge.<ref>L. C. Karpinski "History of Mathematics in the Recent Edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica." ''American Association for the Advancement of Science'' (1912).</ref> |

Al-Khwārizmī's method of solving linear and quadratic equations worked by first reducing the equation to one of six standard forms (where ''b'' and ''c'' are positive integers) | Al-Khwārizmī's method of solving linear and quadratic equations worked by first reducing the equation to one of six standard forms (where ''b'' and ''c'' are positive integers) | ||

| Line 75: | Line 69: | ||

=== Arithmetic === | === Arithmetic === | ||

| − | |||

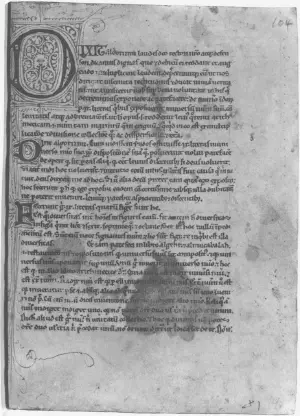

[[Image:Dixit_algorizmi.png|thumb|Page from a Latin translation, beginning with "Dixit algorizmi."]] | [[Image:Dixit_algorizmi.png|thumb|Page from a Latin translation, beginning with "Dixit algorizmi."]] | ||

Al-Khwārizmī's second major work was on the subject of arithmetic, which survived in a [[Latin]] translation but was lost in the original [[Arabic]]. The translation was most likely done in the twelfth century by [[Adelard of Bath]], who had also translated the astronomical tables in 1126. | Al-Khwārizmī's second major work was on the subject of arithmetic, which survived in a [[Latin]] translation but was lost in the original [[Arabic]]. The translation was most likely done in the twelfth century by [[Adelard of Bath]], who had also translated the astronomical tables in 1126. | ||

| − | The Latin manuscripts are untitled, but are commonly referred to by the first two words with which they start: ''Dixit algorizmi'' ("So said al-Khwārizmī"), or ''Algoritmi de numero Indorum'' ("al-Khwārizmī on the Hindu Art of Reckoning"), a name given to the work by [[Baldassarre Boncompagni]] in 1857. The original Arabic title was possibly ''{{unicode|Kitāb al-Jamʿ wa-l-tafrīq bi-ḥisāb al-Hind}}'' | + | The Latin manuscripts are untitled, but are commonly referred to by the first two words with which they start: ''Dixit algorizmi'' ("So said al-Khwārizmī"), or ''Algoritmi de numero Indorum'' ("al-Khwārizmī on the Hindu Art of Reckoning"), a name given to the work by [[Baldassarre Boncompagni]] in 1857. The original Arabic title was possibly ''{{unicode|Kitāb al-Jamʿ wa-l-tafrīq bi-ḥisāb al-Hind}}'' ("The Book of Addition and Subtraction According to the Hindu Calculation")<ref>J. Lennart Berggren, ''Episodes in the Mathematics of Medieval Islam'' (New York: Springer-Verlag, 1986, ISBN 0387963189), 7.</ref> |

| − | Margaret J. Anderson of “Scientists of The Ancient World” states, “One of al-Khwarizmi’s big breakthroughs came from studying the work of Indian mathematicians. In a book called Addition and Subtraction by the Method of Calculation of the Hindus, he introduced the idea of zero to the Western world. Several centuries earlier … [an] unknown Hindu scholar or merchant had wanted to record a number from his counting board. He used a dot to indicate a column with no beads, and called the dot sunya, which means empty. When the idea was adopted by the Arabs, they used the symbol “0” instead of a dot and called it sifr. This gave us our word cipher. Two hundred and fifty years later, the idea of sifr reached Italy, where it was called zenero, which became “zero” in English.” | + | Margaret J. Anderson of “Scientists of The Ancient World” states, “One of al-Khwarizmi’s big breakthroughs came from studying the work of Indian mathematicians. In a book called Addition and Subtraction by the Method of Calculation of the Hindus, he introduced the idea of zero to the Western world. Several centuries earlier … [an] unknown Hindu scholar or merchant had wanted to record a number from his counting board. He used a dot to indicate a column with no beads, and called the dot sunya, which means empty. When the idea was adopted by the Arabs, they used the symbol “0” instead of a dot and called it ''sifr''. This gave us our word cipher. Two hundred and fifty years later, the idea of ''sifr'' reached Italy, where it was called ''zenero'', which became “zero” in English.” |

===Geography === | ===Geography === | ||

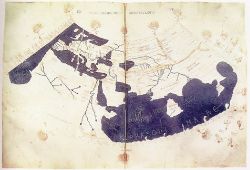

| + | [[Image:PtolemyWorldMap.jpg|thumb|250px|A fifteenth-century map based on Ptolemy's ''Geography'' for comparison.]] | ||

| − | + | Al-Khwārizmī's third major work is his ''{{unicode|Kitāb ṣūrat al-Arḍ}}'' (Arabic: كتاب صورة الأرض "Book on the appearance of the Earth" or "The image of the Earth" translated as ''Geography''), which was finished in 833. It is a revised and completed version of [[Ptolemy]]'s ''[[Geographia (Ptolemy)|Geography]]'', consisting of a list of 2402 coordinates of cities and other geographical features following a general introduction.<ref>[http://www-gap.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/HistTopics/Cartography.html The history of cartography] Retrieved September 27, 2016.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | Al-Khwārizmī's third major work is his ''{{unicode|Kitāb ṣūrat al-Arḍ}}'' (Arabic: كتاب صورة الأرض "Book on the appearance of the Earth" or "The image of the Earth" translated as ''Geography''), which was finished in 833. It is a revised and completed version of [[Ptolemy]]'s ''[[Geographia (Ptolemy)|Geography]]'', consisting of a list of 2402 coordinates of cities and other geographical features following a general introduction.<ref>[http://www-gap.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/HistTopics/Cartography.html | ||

| − | There is only one surviving copy of ''{{unicode|Kitāb ṣūrat al-Arḍ}}'', which is kept at the [[Strasbourg University Library]]. A Latin translation is kept at the [[Biblioteca Nacional de España]] in [[Madrid]]. The complete title translates as ''Book of the appearance of the Earth, with its cities, mountains, seas, all the islands and rivers, written by Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwārizmī, according to the geographical treatise written by Ptolemy the Claudian''.<ref>In al-Khwārizmī's opinion, "the Claudian" indicated that Ptolemy was a | + | There is only one surviving copy of ''{{unicode|Kitāb ṣūrat al-Arḍ}}'', which is kept at the [[Strasbourg University Library]]. A Latin translation is kept at the [[Biblioteca Nacional de España]] in [[Madrid]]. The complete title translates as ''Book of the appearance of the Earth, with its cities, mountains, seas, all the islands and rivers, written by Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwārizmī, according to the geographical treatise written by Ptolemy the Claudian''.<ref>In al-Khwārizmī's opinion, "the Claudian" indicated that Ptolemy was a descendant of the emperor Claudius.</ref> |

The book opens with the list of [[latitudes]] and [[longitudes]], in order of "[[weather zones]]," that is to say in blocks of latitudes and, in each weather zone, by order of longitude. As [[Paul Gallez]] points out, this excellent system allows us to deduce many latitudes and longitudes where the only document in our possession is in such a bad condition as to make it practically illegible. | The book opens with the list of [[latitudes]] and [[longitudes]], in order of "[[weather zones]]," that is to say in blocks of latitudes and, in each weather zone, by order of longitude. As [[Paul Gallez]] points out, this excellent system allows us to deduce many latitudes and longitudes where the only document in our possession is in such a bad condition as to make it practically illegible. | ||

| − | Neither the Arabic copy nor the Latin translation include the map of the world itself, however [[Hubert Daunicht]] was able to reconstruct the missing map from the list of coordinates. Daunicht read the latitudes and longitudes of the coastal points in the manuscript, or deduces them from the context where they were not legible. He transferred the points onto [[graph paper]] and connected them with straight lines, obtaining an approximation of the coastline as it was on the original map. He then does the same for the rivers and towns.<ref>Daunicht | + | Neither the Arabic copy nor the Latin translation include the map of the world itself, however [[Hubert Daunicht]] was able to reconstruct the missing map from the list of coordinates. Daunicht read the latitudes and longitudes of the coastal points in the manuscript, or deduces them from the context where they were not legible. He transferred the points onto [[graph paper]] and connected them with straight lines, obtaining an approximation of the coastline as it was on the original map. He then does the same for the rivers and towns.<ref>Hubert Daunicht, "Der Osten nach der Erdkarte al-Ḫuwārizmīs: Beiträge zur historischen Geographie und Geschichte Asiens" ''Bonner orientalistische Studien'', 1968.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

=== Astronomy === | === Astronomy === | ||

| − | |||

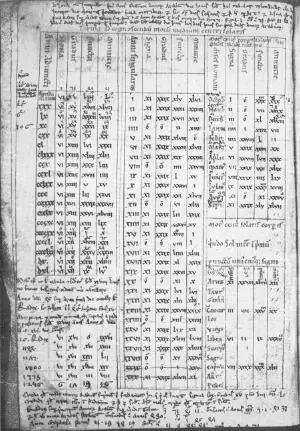

[[Image:Corpus Christ College MS 283 (1).png|thumb|Corpus Christi College MS 283]] | [[Image:Corpus Christ College MS 283 (1).png|thumb|Corpus Christi College MS 283]] | ||

| − | {{unicode|Al-Khwārizmī's ''Zīj al-sindhind''}} | + | {{unicode|Al-Khwārizmī's ''Zīj al-sindhind''}} (Arabic: زيج "astronomical tables") is a work consisting of approximately 37 chapters on calendrical and astronomical calculations and 116 tables with calendrical, astronomical and astrological data, as well as a table of [[sine]] values. This is one of many Arabic [[zij]]es based on the [[Indian astronomy|Indian astronomical]] methods known as the ''sindhind''.<ref>E.S. Kennedy, "A Survey of Islamic Astronomical Tables" ''Transactions of the American Philosophical Society'' 46(2), Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1956, 26-29.</ref> |

| − | The original Arabic version (written c. 820) is lost, but a version by the Spanish astronomer [[Maslama al-Majrīṭī]] (c. 1000) has survived in a Latin translation, presumably by [[Adelard of Bath]] (January 26, 1126).<ref>Neugebauer 1962</ref> The four surviving manuscripts of the Latin translation are kept at the Bibliothèque publique (Chartres), the Bibliothèque Mazarine (Paris), the Bibliotheca Nacional (Madrid) and the Bodleian Library (Oxford). | + | The original Arabic version (written c. 820) is lost, but a version by the Spanish astronomer [[Maslama al-Majrīṭī]] (c. 1000) has survived in a Latin translation, presumably by [[Adelard of Bath]] (January 26, 1126).<ref>Otto Neugebauer, "The Astronomical Tables of al-Khwarizmi" ''Historisk-filosofiske Skrifter'' 4(2) (1962).</ref> The four surviving manuscripts of the Latin translation are kept at the Bibliothèque publique (Chartres), the Bibliothèque Mazarine (Paris), the Bibliotheca Nacional (Madrid) and the Bodleian Library (Oxford). |

=== Jewish calendar === | === Jewish calendar === | ||

| − | + | Al-Khwārizmī wrote several other works including a treatise on the [[Jewish calendar]] (''{{unicode|Risāla fi istikhrāj taʾrīkh al-yahūd}}'' "Extraction of the Jewish Era"). It describes the [[Metonic cycle|19-year intercalation cycle]], the rules for determining on what day of the week the first day of the month [[Tishrei|Tishrī]] shall fall; calculates the interval between the [[Anno Mundi|Jewish era]] (creation of Adam) and the [[Seleucid era]]; and gives rules for determining the mean longitude of the sun and the moon using the Jewish calendar. Similar material is found in the works of [[al-Bīrūnī]] and [[Maimonides]]. | |

| − | Al-Khwārizmī wrote several other works including a treatise on the [[Jewish calendar]] (''{{unicode|Risāla fi istikhrāj taʾrīkh al-yahūd}}'' "Extraction of the Jewish Era"). It describes the [[Metonic cycle|19-year intercalation cycle]], the rules for determining on what day of the week the first day of the month [[Tishrei|Tishrī]] shall fall; calculates the interval between the [[Anno Mundi|Jewish era]] (creation of Adam) and the [[Seleucid era]]; and gives rules for determining the mean longitude of the sun and the moon using the Jewish calendar. Similar material is found in the works of [[al-Bīrūnī]] and [[Maimonides]]. | ||

=== Other works === | === Other works === | ||

| − | |||

Several Arabic manuscripts in Berlin, Istanbul, Taschkent, Cairo and Paris contain further material that surely or with some probability comes from al-Khwārizmī. The Istanbul manuscript contains a paper on sundials, which is mentioned in the ''Fihirst''. Other papers, such as one on the determination of the direction of [[Mecca]], are on the [[spherical astronomy]]. | Several Arabic manuscripts in Berlin, Istanbul, Taschkent, Cairo and Paris contain further material that surely or with some probability comes from al-Khwārizmī. The Istanbul manuscript contains a paper on sundials, which is mentioned in the ''Fihirst''. Other papers, such as one on the determination of the direction of [[Mecca]], are on the [[spherical astronomy]]. | ||

| − | Two texts deserve special interest on the [[morning width]] (''Maʿrifat saʿat al-mashriq fī kull balad'') and the determination of the [[azimuth]] from a height | + | Two texts deserve special interest on the [[morning width]] (''Maʿrifat saʿat al-mashriq fī kull balad'') and the determination of the [[azimuth]] from a height |

He also wrote two books on using and constructing [[astrolabe]]s. [[Ibn al-Nadim]] in his ''{{unicode|[[Kitab al-Fihrist]]}}'' (an index of Arabic books) also mentions ''{{unicode|Kitāb ar-Ruḵāma(t)}}'' (the book on [[sundial]]s) and ''{{unicode|Kitab al-Tarikh}}'' (the book of [[history]]) but the two have been lost. | He also wrote two books on using and constructing [[astrolabe]]s. [[Ibn al-Nadim]] in his ''{{unicode|[[Kitab al-Fihrist]]}}'' (an index of Arabic books) also mentions ''{{unicode|Kitāb ar-Ruḵāma(t)}}'' (the book on [[sundial]]s) and ''{{unicode|Kitab al-Tarikh}}'' (the book of [[history]]) but the two have been lost. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| + | <references /> | ||

| − | + | == References== | |

| − | + | *Berggren, J. Lennart. ''Episodes in the Mathematics of Medieval Islam''. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1986 ISBN 0387963189 | |

| − | + | *Daffa', Abdullah al-. ''The Muslim contribution to mathematics''. London, Croom Helm: 1977. ISBN 0856644641 | |

| − | + | *Daunicht, Hubert. ''Der Osten nach der Erdkarte al-Ḫuwārizmīs: Beiträge zur historischen Geographie und Geschichte Asiens''. Bonner orientalistische Studien, 1968–1970. {{LCCN|71||468286}} | |

| + | *Dunlop, Douglas Morton. "Muhammad ibn-Musa al-Khwarizmi" ''Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland'' (1943): 248–250. | ||

| + | *Folkerts, Menso. ''Die älteste lateinische Schrift über das indische Rechnen nach al-Ḫwārizmī''. München: Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1997. ISBN 3769601084 | ||

| + | *Gandz, Solomon. "The Origin of the Term 'Algebra'" ''The American Mathematical Monthly'' 33(9) (1926, November): 437–440. {{ISSN|0002-9890}} | ||

| + | *Gandz, Solomon. "The Sources of al-Khowārizmī's Algebra" ''Osiris'' 1 (1936): 263–277. {{ISSN|0369-7827}} | ||

| + | *Gandz, Solomon. "The Algebra of Inheritance: A Rehabilitation of Al-Khuwārizmī" ''Osiris'' 5 (1938): 319–391. {{ISSN|0369-7827}} | ||

| + | *Hogendijk, Jan P. "Al-Khwārizmī's Table of the 'Sine of the Hours' and the Underlying Sine Table" ''Historia Scientiarum'' 42 (1991): 1–12. | ||

| + | *Hogendijk, Jan P. ''al-Khwarzimi'' ''Pythagoras'' 38(2) (1998): 4–5. {{ISSN|0033-4766}} | ||

| + | *Hughes, Barnabas B. "Gererd of Cremona's Translation of al-Khwārizmī's al-Jabr: A Critical Edition" ''Mediaeval Studies'' 48 (1986): 211–263. | ||

| + | *Hughes, Barnabas. ''Robert of Chester's Latin translation of al-Khwarizmi's al-Jabr: A new critical edition''. In Latin. F. Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden, 1989. ISBN 3515045899 | ||

| + | * Karpinski, L. C. ''Robert of Chester's Latin Translation of the Algebra of Al-Khowarizmi'' The Macmillan Company, 1915. | ||

| + | * Kennedy, E.S. ''A Survey of Islamic Astronomical Tables''. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 46(2), Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1956. | ||

| + | *Kennedy, E.S. "Al-Khwārizmī on the Jewish Calendar" ''Scripta Mathematica'' 27 (1964): 55–59. | ||

| + | *King, David A. ''Al-Khwārizmī and New Trends in Mathematical Astronomy in the Ninth Century''. New York University: Hagop Kevorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies: Occasional Papers on the Near East '''2''', 1983. {{LCCN|85||150177}} | ||

| + | *Mžik, Hanz von. ''Das Kitāb Ṣūrat al-Arḍ des Abū Ǧa‘far Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Ḫuwārizmī''. Leipzig, 1926. | ||

| + | *Neugebauer, Otto. "The Astronomical Tables of al-Khwarizmi" ''Historisk-filosofiske Skrifter'' 4(2) (1962). | ||

| + | *Oaks, Jeffrey A. [http://facstaff.uindy.edu/~oaks/MHMC.htm ''Was al-Khwarizmi an applied Algebraist?'']. The University of Indianapolis. Retrieved September 26, 2016. | ||

| + | *Rashed, Roshdi. ''The development of Arabic mathematics: between arithmetic and Algebra''. Springer, 2013. ISBN 978-9048143382 | ||

| + | *Rosen, Fredrick. ''The Algebra of Mohammed Ben Musa''. Kessinger Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1417949147 | ||

| + | *Rosenfeld, Boris A. "Geometric trigonometry in Treatises of al-Khwārizmī, al-Māhānī and Ibn al-Haytham" ''Vestiga mathematica: Studies in Medieval and Early Modern Mathematics in Honour of H. L. L. Busard'' Menso Folkerts and J. P. Hogendijk (eds.). Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1993. ISBN 9051835361 | ||

| + | *Sezgin, Fuat. ''Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums''. Leiden, the Netherlands: E. J. Brill, 1974. | ||

| + | *Sezgin, Fuat (ed.). ''Islamic Mathematics and Astronomy''. Frankfurt: Institut für Geschichte der arabisch-islamischen Wissenschaften, 1997-9. | ||

| + | *Struik, Dirk Jan. ''A Concise History of Mathematics''. Dover Publications, 1987. ISBN 0486602559 | ||

| + | *Suter, H. (ed.). ''Die astronomischen Tafeln des Muhammed ibn Mûsâ al-Khwârizmî in der Bearbeitung des Maslama ibn Ahmed al-Madjrîtî und der latein''. Übersetzung des Athelhard von Bath auf Grund der Vorarbeiten von A. Bjørnbo und R. Besthorn in Kopenhagen. Hrsg. und komm. Kopenhagen 1914. 288 pp. Repr. 1997 (Islamic Mathematics and Astronomy. 7). ISBN 382984008X | ||

| + | *Toomer, Gerald. "Al-Khwārizmī, Abu Jaʿfar Muḥammad ibn Mūsā" Charles Coulston Gillispie (ed.), ''Dictionary of Scientific Biography'' Volume 7. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1970–1990, 358–365 ISBN 0684169622 | ||

| + | *Van Dalen, B. ''Al-Khwarizmi's Astronomical Tables Revisited: Analysis of the Equation of Time''. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Mathematicians]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{credits|Muhammad_ibn_Mūsā_al-Khwārizmī|138399405}} | {{credits|Muhammad_ibn_Mūsā_al-Khwārizmī|138399405}} | ||

Latest revision as of 17:58, 10 November 2022

| Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī |

|---|

A stamp issued September 6, 1983 in the Soviet Union, commemorating al-Khwārizmī's (approximate) 1200th anniversary.

|

| Born |

| c. 780 |

| Died |

| c. 850 |

Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī (Arabic: محمد بن موسى الخوارزمي) was a Persian mathematician, astronomer, astrologer and geographer. He was born around 780 in Khwārizm (now Khiva, Uzbekistan) and died around 850. He worked most of his life as a scholar in the House of Wisdom in Baghdad.

His Algebra was the first book on the systematic solution of linear and quadratic equations. Consequently he is considered to be the father of algebra,[1] a title he shares with Diophantus. Latin translations of his Arithmetic, on the Indian numerals, introduced the decimal positional number system to the Western world in the twelfth century.[2] He revised and updated Ptolemy's Geography as well as writing several works on astronomy and astrology.

His contributions not only made a great impact on mathematics, but on language as well. The word algebra is derived from al-jabr, one of the two operations used to solve quadratic equations, as described in his book. The words algorism and algorithm stem from algoritmi, the Latinization of his name.[3] His name is also the origin of the Spanish word guarismo[4] and of the Portuguese word algarismo, both meaning "digit."

Biography

Few details about al-Khwārizmī's life are known; it is not even certain exactly where he was born. His name indicates he might have come from Khwarizm (Khiva) in the Khorasan province of the Abbasid empire (now Xorazm Province of Uzbekistan).

His kunya is given as either Abū ʿAbd Allāh (Arabic: أبو عبد الله) or Abū Jaʿfar.[5]

With his full name of Abu Ja’far Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, historians are able to extract that he was the son of Moses, the father of Ja’far. Either he or his ancestors came from Khiva (then Khwarazm), which is a city south of the Aral Sea in central Asia. That this city lies between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers remains under discussion.

The historian al-Tabari gave his name as Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwārizmī al-Majousi al-Katarbali (Arabic: محمد بن موسى الخوارزميّ المجوسيّ القطربّليّ). The epithet al-Qutrubbulli indicates he might instead have came from Qutrubbull, a small town near Baghdad. Regarding al-Khwārizmī's religion, Toomer writes:

Another epithet given to him by al-Ṭabarī, "al-Majūsī," would seem to indicate that he was an adherent of the old Zoroastrian religion. This would still have been possible at that time for a man of Iranian origin, but the pious preface to al-Khwārizmī's Algebra shows that he was an orthodox Muslim, so al-Ṭabarī's epithet could mean no more than that his forebears, and perhaps he in his youth, had been a Zoroastrian.[6]

Al-Khwārizmī accomplished most of his work in the period between 813 and 833. After the Islamic conquest of Persia, Baghdad became the centre of scientific studies and trade, and many merchants and scientists, from as far as China and India, traveled to this city—and apparently, so did Al-Khwārizmī. He worked in Baghdad as a scholar at the House of Wisdom established by Caliph al-Maʾmūn, where he studied the sciences and mathematics, which included the translation of Greek and Sanskrit scientific manuscripts.

In Scientists of The Ancient World, Margaret J. Anderson states:

When al-Khwarizmi lived in Baghdad it was quite a new city, but its location at the meeting place of trade routes from India, Persia, and ports on the Mediterranean Sea had caused it to grow rapidly. From 813 to 823, Baghdad was ruled by the caliph (spiritual and political leader) al-Ma’mun. The caliph, who himself was an enthusiastic scholar and philosopher, soon turned the city into an important intellectual center. He established the House of Wisdom and ordered his scholars to translate the classical Greek texts into Arabic. Copies of these books ended up in Muslim centers of learning in Spain and Sicily. Later, they were translated into Latin and passed on to universities throughout Europe.

Contributions

His major contributions to mathematics, astronomy, astrology, geography and cartography provided foundations for later and even more widespread innovation in Algebra, trigonometry, and his other areas of interest. His systematic and logical approach to solving linear and quadratic equations gave shape to the discipline of Algebra, a word that is derived from the name of his 830 book on the subject, al-Kitab al-mukhtasar fi hisab al-jabr wa'l-muqabala (Arabic الكتاب المختصر في حساب الجبر والمقابلة) or: "The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing." The book was first translated into Latin in the twelfth century.

His book On the Calculation with Hindu Numerals written about 825, was principally responsible for the diffusion of the Indian system of numeration in the Middle-East and then Europe. This book was also translated into Latin in the twelfth century, as Algoritmi de numero Indorum. It was from the name of the author, rendered in Latin as algoritmi, that originated the term algorithm.

Some of al-Khwarizmi’s contributions were based on earlier Persian and Babylonian Astronomy, Indian numbers, and Greek sources.

Al-Khwārizmī systematized and corrected Ptolemy's data in geography with regards to Africa and the Middle East. Another major book was his Kitab surat al-ard ("The Image of the Earth"; translated as Geography), which presented the coordinates of localities in the known world based, ultimately, on those in the Geography of Ptolemy but with improved values for the length of the Mediterranean Sea and the location of cities in Asia and Africa.

He also assisted in the construction of a world map for the caliph al-Ma'mun and participated in a project to determine the circumference of the Earth, supervising the work of 70 geographers to create the map of the then "known world".

When his work was copied and transferred to Europe through Latin translations, it had a profound impact on the advancement of basic mathematics in Europe. He also wrote on mechanical devices like the astrolabe and sundial.

Algebra

al-Kitāb al-mukhtaṣar fī ḥisāb al-jabr wa-l-muqābala (Arabic: الكتاب المختصر في حساب الجبر والمقابلة “The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing”) is a mathematical book written approximately 830 C.E.

The book is considered to have defined Algebra. The word Algebra is derived from the name of one of the basic operations with equations (al-jabr) described in this book. The book was translated in Latin as Liber Algebrae et Almucabala by Robert of Chester (Segovia, 1145)[7] hence "Algebra," and also by Gerard of Cremona. A unique Arabic copy is kept at Oxford and was translated in 1831 by F. Rosen. A Latin translation is kept is Cambridge.[8]

Al-Khwārizmī's method of solving linear and quadratic equations worked by first reducing the equation to one of six standard forms (where b and c are positive integers)

- squares equal roots (ax2 = bx)

- squares equal number (ax2 = c)

- roots equal number (bx = c)

- squares and roots equal number (ax2 + bx = c)

- squares and number equal roots (ax2 + c = bx)

- roots and number equal squares (bx + c = ax2)

by dividing out the coefficient of the square and using the two operations al-ǧabr (Arabic: الجبر “restoring” or “completion”) and al-muqābala ("balancing"). Al-ǧabr is the process of removing negative units, roots and squares from the equation by adding the same quantity to each side. For example, x2 = 40x - 4x2 is reduced to 5x2 = 40x. Al-muqābala is the process of bringing quantities of the same type to the same side of the equation. For example, x2+14 = x+5 is reduced to x2+9 = x.

Several authors have published texts under the name of Kitāb al-ǧabr wa-l-muqābala, including Abū Ḥanīfa al-Dīnawarī, Abū Kāmil (Rasāla fi al-ǧabr wa-al-muqābala), Abū Muḥammad al-ʿAdlī, Abū Yūsuf al-Miṣṣīṣī, Ibn Turk, Sind ibn ʿAlī, Sahl ibn Bišr (author uncertain), and Šarafaddīn al-Ṭūsī.

Arithmetic

Al-Khwārizmī's second major work was on the subject of arithmetic, which survived in a Latin translation but was lost in the original Arabic. The translation was most likely done in the twelfth century by Adelard of Bath, who had also translated the astronomical tables in 1126.

The Latin manuscripts are untitled, but are commonly referred to by the first two words with which they start: Dixit algorizmi ("So said al-Khwārizmī"), or Algoritmi de numero Indorum ("al-Khwārizmī on the Hindu Art of Reckoning"), a name given to the work by Baldassarre Boncompagni in 1857. The original Arabic title was possibly Kitāb al-Jamʿ wa-l-tafrīq bi-ḥisāb al-Hind ("The Book of Addition and Subtraction According to the Hindu Calculation")[9]

Margaret J. Anderson of “Scientists of The Ancient World” states, “One of al-Khwarizmi’s big breakthroughs came from studying the work of Indian mathematicians. In a book called Addition and Subtraction by the Method of Calculation of the Hindus, he introduced the idea of zero to the Western world. Several centuries earlier … [an] unknown Hindu scholar or merchant had wanted to record a number from his counting board. He used a dot to indicate a column with no beads, and called the dot sunya, which means empty. When the idea was adopted by the Arabs, they used the symbol “0” instead of a dot and called it sifr. This gave us our word cipher. Two hundred and fifty years later, the idea of sifr reached Italy, where it was called zenero, which became “zero” in English.”

Geography

Al-Khwārizmī's third major work is his Kitāb ṣūrat al-Arḍ (Arabic: كتاب صورة الأرض "Book on the appearance of the Earth" or "The image of the Earth" translated as Geography), which was finished in 833. It is a revised and completed version of Ptolemy's Geography, consisting of a list of 2402 coordinates of cities and other geographical features following a general introduction.[10]

There is only one surviving copy of Kitāb ṣūrat al-Arḍ, which is kept at the Strasbourg University Library. A Latin translation is kept at the Biblioteca Nacional de España in Madrid. The complete title translates as Book of the appearance of the Earth, with its cities, mountains, seas, all the islands and rivers, written by Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwārizmī, according to the geographical treatise written by Ptolemy the Claudian.[11]

The book opens with the list of latitudes and longitudes, in order of "weather zones," that is to say in blocks of latitudes and, in each weather zone, by order of longitude. As Paul Gallez points out, this excellent system allows us to deduce many latitudes and longitudes where the only document in our possession is in such a bad condition as to make it practically illegible.

Neither the Arabic copy nor the Latin translation include the map of the world itself, however Hubert Daunicht was able to reconstruct the missing map from the list of coordinates. Daunicht read the latitudes and longitudes of the coastal points in the manuscript, or deduces them from the context where they were not legible. He transferred the points onto graph paper and connected them with straight lines, obtaining an approximation of the coastline as it was on the original map. He then does the same for the rivers and towns.[12]

Astronomy

Al-Khwārizmī's Zīj al-sindhind (Arabic: زيج "astronomical tables") is a work consisting of approximately 37 chapters on calendrical and astronomical calculations and 116 tables with calendrical, astronomical and astrological data, as well as a table of sine values. This is one of many Arabic zijes based on the Indian astronomical methods known as the sindhind.[13]

The original Arabic version (written c. 820) is lost, but a version by the Spanish astronomer Maslama al-Majrīṭī (c. 1000) has survived in a Latin translation, presumably by Adelard of Bath (January 26, 1126).[14] The four surviving manuscripts of the Latin translation are kept at the Bibliothèque publique (Chartres), the Bibliothèque Mazarine (Paris), the Bibliotheca Nacional (Madrid) and the Bodleian Library (Oxford).

Jewish calendar

Al-Khwārizmī wrote several other works including a treatise on the Jewish calendar (Risāla fi istikhrāj taʾrīkh al-yahūd "Extraction of the Jewish Era"). It describes the 19-year intercalation cycle, the rules for determining on what day of the week the first day of the month Tishrī shall fall; calculates the interval between the Jewish era (creation of Adam) and the Seleucid era; and gives rules for determining the mean longitude of the sun and the moon using the Jewish calendar. Similar material is found in the works of al-Bīrūnī and Maimonides.

Other works

Several Arabic manuscripts in Berlin, Istanbul, Taschkent, Cairo and Paris contain further material that surely or with some probability comes from al-Khwārizmī. The Istanbul manuscript contains a paper on sundials, which is mentioned in the Fihirst. Other papers, such as one on the determination of the direction of Mecca, are on the spherical astronomy.

Two texts deserve special interest on the morning width (Maʿrifat saʿat al-mashriq fī kull balad) and the determination of the azimuth from a height

He also wrote two books on using and constructing astrolabes. Ibn al-Nadim in his Kitab al-Fihrist (an index of Arabic books) also mentions Kitāb ar-Ruḵāma(t) (the book on sundials) and Kitab al-Tarikh (the book of history) but the two have been lost.

Notes

- ↑ Solomon Gandz, "The Sources of al-Khowārizmī's Algebra" Osiris 1 (1936): 263–277.

- ↑ Dirk Jan Struik, A Concise History of Mathematics (Dover Publications, 1987, ISBN 0486602559), 93.

- ↑ Abdullah al-Daffa', The Muslim contribution to mathematics (London, Croom Helm, 1977, ISBN 0856644641).

- ↑ Donald E. Knuth, Algorithms in Modern Mathematics and Computer Science (Springer-Verlag, 1979, ISBN 0387111573).

- ↑ possibly because it is mistaken with that of Ǧaʿfar Muḥammad ibn Mūsā ibn Šākir. M. Dunlop. Muḥammad b. Mūsā al-Khwārizmī. JRAS 1943, 248-250).

- ↑ Gerald Toomer, "Al-Khwārizmī, Abu Jaʿfar Muḥammad ibn Mūsā" Charles Coulston Gillispie (ed.), Dictionary of Scientific Biography Volume 7 (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1970–1990), 358–365.

- ↑ mactutor-hanasi

- ↑ L. C. Karpinski "History of Mathematics in the Recent Edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica." American Association for the Advancement of Science (1912).

- ↑ J. Lennart Berggren, Episodes in the Mathematics of Medieval Islam (New York: Springer-Verlag, 1986, ISBN 0387963189), 7.

- ↑ The history of cartography Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- ↑ In al-Khwārizmī's opinion, "the Claudian" indicated that Ptolemy was a descendant of the emperor Claudius.

- ↑ Hubert Daunicht, "Der Osten nach der Erdkarte al-Ḫuwārizmīs: Beiträge zur historischen Geographie und Geschichte Asiens" Bonner orientalistische Studien, 1968.

- ↑ E.S. Kennedy, "A Survey of Islamic Astronomical Tables" Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 46(2), Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1956, 26-29.

- ↑ Otto Neugebauer, "The Astronomical Tables of al-Khwarizmi" Historisk-filosofiske Skrifter 4(2) (1962).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Berggren, J. Lennart. Episodes in the Mathematics of Medieval Islam. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1986 ISBN 0387963189

- Daffa', Abdullah al-. The Muslim contribution to mathematics. London, Croom Helm: 1977. ISBN 0856644641

- Daunicht, Hubert. Der Osten nach der Erdkarte al-Ḫuwārizmīs: Beiträge zur historischen Geographie und Geschichte Asiens. Bonner orientalistische Studien, 1968–1970. LCCN 71-468286

- Dunlop, Douglas Morton. "Muhammad ibn-Musa al-Khwarizmi" Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland (1943): 248–250.

- Folkerts, Menso. Die älteste lateinische Schrift über das indische Rechnen nach al-Ḫwārizmī. München: Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1997. ISBN 3769601084

- Gandz, Solomon. "The Origin of the Term 'Algebra'" The American Mathematical Monthly 33(9) (1926, November): 437–440. ISSN 0002-9890

- Gandz, Solomon. "The Sources of al-Khowārizmī's Algebra" Osiris 1 (1936): 263–277. ISSN 0369-7827

- Gandz, Solomon. "The Algebra of Inheritance: A Rehabilitation of Al-Khuwārizmī" Osiris 5 (1938): 319–391. ISSN 0369-7827

- Hogendijk, Jan P. "Al-Khwārizmī's Table of the 'Sine of the Hours' and the Underlying Sine Table" Historia Scientiarum 42 (1991): 1–12.

- Hogendijk, Jan P. al-Khwarzimi Pythagoras 38(2) (1998): 4–5. ISSN 0033-4766

- Hughes, Barnabas B. "Gererd of Cremona's Translation of al-Khwārizmī's al-Jabr: A Critical Edition" Mediaeval Studies 48 (1986): 211–263.

- Hughes, Barnabas. Robert of Chester's Latin translation of al-Khwarizmi's al-Jabr: A new critical edition. In Latin. F. Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden, 1989. ISBN 3515045899

- Karpinski, L. C. Robert of Chester's Latin Translation of the Algebra of Al-Khowarizmi The Macmillan Company, 1915.

- Kennedy, E.S. A Survey of Islamic Astronomical Tables. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 46(2), Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1956.

- Kennedy, E.S. "Al-Khwārizmī on the Jewish Calendar" Scripta Mathematica 27 (1964): 55–59.

- King, David A. Al-Khwārizmī and New Trends in Mathematical Astronomy in the Ninth Century. New York University: Hagop Kevorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies: Occasional Papers on the Near East 2, 1983. LCCN 85-150177

- Mžik, Hanz von. Das Kitāb Ṣūrat al-Arḍ des Abū Ǧa‘far Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Ḫuwārizmī. Leipzig, 1926.

- Neugebauer, Otto. "The Astronomical Tables of al-Khwarizmi" Historisk-filosofiske Skrifter 4(2) (1962).

- Oaks, Jeffrey A. Was al-Khwarizmi an applied Algebraist?. The University of Indianapolis. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- Rashed, Roshdi. The development of Arabic mathematics: between arithmetic and Algebra. Springer, 2013. ISBN 978-9048143382

- Rosen, Fredrick. The Algebra of Mohammed Ben Musa. Kessinger Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1417949147

- Rosenfeld, Boris A. "Geometric trigonometry in Treatises of al-Khwārizmī, al-Māhānī and Ibn al-Haytham" Vestiga mathematica: Studies in Medieval and Early Modern Mathematics in Honour of H. L. L. Busard Menso Folkerts and J. P. Hogendijk (eds.). Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1993. ISBN 9051835361

- Sezgin, Fuat. Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums. Leiden, the Netherlands: E. J. Brill, 1974.

- Sezgin, Fuat (ed.). Islamic Mathematics and Astronomy. Frankfurt: Institut für Geschichte der arabisch-islamischen Wissenschaften, 1997-9.

- Struik, Dirk Jan. A Concise History of Mathematics. Dover Publications, 1987. ISBN 0486602559

- Suter, H. (ed.). Die astronomischen Tafeln des Muhammed ibn Mûsâ al-Khwârizmî in der Bearbeitung des Maslama ibn Ahmed al-Madjrîtî und der latein. Übersetzung des Athelhard von Bath auf Grund der Vorarbeiten von A. Bjørnbo und R. Besthorn in Kopenhagen. Hrsg. und komm. Kopenhagen 1914. 288 pp. Repr. 1997 (Islamic Mathematics and Astronomy. 7). ISBN 382984008X

- Toomer, Gerald. "Al-Khwārizmī, Abu Jaʿfar Muḥammad ibn Mūsā" Charles Coulston Gillispie (ed.), Dictionary of Scientific Biography Volume 7. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1970–1990, 358–365 ISBN 0684169622

- Van Dalen, B. Al-Khwarizmi's Astronomical Tables Revisited: Analysis of the Equation of Time.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.