Difference between revisions of "Minimum wage" - New World Encyclopedia

(Copied from wikipedia) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (62 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}}{{copyedited}} |

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Economics]] | [[Category:Economics]] | ||

| + | '''Minimum wage''' is the minimum amount of compensation an employee must receive for performing [[labor]]; usually calculated per hour. Minimum wages are typically established by [[contract]], [[collective bargaining]], or legislation by the [[government]]. Thus, it is illegal to pay an employee less than the minimum wage. Employers may pay employees by some other method than hourly, such as by piecework or commission; the rate when calculated on an hourly basis must equal at least the current minimum wage per hour. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | The intent of minimum wage legislation is to to avoid exploitation of workers and ensure that all members in the society who put in legitimate time at work are compensated at a rate that allows them to live within that society with adequate food, housing, clothes, and other essentials. Such intent reflects the emerging human consciousness of [[human rights]] and the desire for a world of harmony and prosperity for all. Both economic theory and practice, however, suggest that mandating a minimum monetary compensation for work performed is not sufficient by itself to guarantee improvements in the quality of life of all members of society. | ||

| + | ==Definition== | ||

| + | The '''minimum wage''' is defined as the minimum compensation that an employee must receive for their labor. For an employer to pay less is illegal and subject to penalties. The minimum wage is established by government legislation or [[collective bargaining]]. | ||

| + | For example, in the [[United States]], the minimum wage for eligible employees under Federal law is $7.25 per hour, effective July 24, 2009. Many states also have minimum wage laws, which guarantee a higher minimum wage. | ||

| + | ==Historical and theoretical overview== | ||

| + | In defending and advancing the interests of ordinary working people, [[trade union]]s seek to raise wages and improve working conditions, and thus to raise the human condition in society generally. This quest has sustained and motivated unionists for the better part of 200 years. | ||

| − | + | Many supporters of the minimum wage assert that it is a matter of [[social justice]] that helps reduce [[exploitation]] and ensures workers can afford what they consider to be basic necessities. | |

| − | + | ===Historical roots=== | |

| + | In 1896, [[New Zealand]] established arbitration boards with the Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act).<ref name="Cost of Living">American Academy of Political and Social Science, ''The Cost of Living'' (Philadelphia, 1913).</ref> Also in 1896, in [[Victoria (Australia)|Victoria]], [[Australia]], an amendment to the Factories Act provided for the creation of a wages board.<ref name="Cost of Living"/> The wages board did not set a universal minimum wage, but set basic wages for six industries that were considered to pay low wages. | ||

| − | + | Legally, a minimum wage being the lowest hourly, daily, or monthly wage that employers may pay to employees or workers, was first enacted in Australia via the 1907 “Harvester judgment” which made reference to basic wages. The Harvester judgment was the first attempt at establishing a wage based upon needs, below which no worker should be expected to live. | |

| − | + | Also in 1907, [[Ernest Aves]] was sent by the [[Great Britain|British]] Secretary of State for the Home Department to investigate the results of the minimum wage laws in Australia and New Zealand. In part as a result of his report, [[Winston Churchill]], then president of the Board of Trade, introduced the Trade Boards Act on March 24, 1909, establishing trade boards to set minimum wage rates in certain industries. It became law in October of that year, and went into effect in January 1911. | |

| − | + | [[Massachusetts]] passed the first state minimum wage law in 1912, after a committee had shown the nation that women and children were working long hours at wages barely sufficient to maintain a meager existence. By 1923, 17 states had adopted minimum wage legislation mainly for women and minors in a variety of industries and occupations. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In the [[United States]], statutory minimum wages were first introduced nationally in 1938.<ref>Sanjiv Sachdev, ''Raising the Rate: An Evaluation of the Uprating Mechanism for the Minimum Wage'' (Employee Relations, 2003).</ref> In addition to the federal minimum wage, nearly all states within the United States have their own minimum wage laws with the exception of [[South Carolina]], [[Tennessee]], [[Alabama]], [[Mississippi]], and [[Louisiana]].<ref>www.dol.gov, [https://www.dol.gov/whd/minwage/america.htm Minimum Wage Laws in the States - January 1, 2017] Retrieved January 11, 2017.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | In the [[ | ||

| − | + | In the 1960s, minimum wage laws were introduced into [[Latin America]] as part of the [[Alliance for Progress]]; however these minimum wages were, and are, low. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In the [[European Union]], 22 out of 28 member states had national minimum wages as of 2016.<ref>Karel Fric, [http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/observatories/eurwork/articles/working-conditions-industrial-relations/statutory-minimum-wages-in-the-eu-2016 Statutory minimum wages in the EU 2016] European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, January 29, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2017.</ref> Northern manufacturing firms lobbied for the minimum wage so as to prevent firms located in the south, where labor was cheaper, from competing. Many countries, such as [[Norway]], [[Sweden]], [[Finland]], [[Denmark]], [[Switzerland]], [[Germany]], [[Austria]], [[Italy]], and [[Cyprus]] have no minimum wage laws, but rely on employer groups and [[trade union]]s to set minimum earnings through [[collective bargaining]].<ref>Ronald G. Ehrenberg, ''Labor Markets and Integrating National Economies'' (Brookings Institution Press, 1994), p. 41.</ref> | |

| − | + | The International Labour Office in Geneva, Switzerland reports that some 90 percent of countries around the world have legislation supporting a minimum wage. The minimum wage in countries that rank within the lowest 20 percent of the pay scale is less than $2 per day, or about $57 per month. The minimum wage in the countries that represent the highest 20 percent of the pay scale is about $40 per day, or about $1,185 per month. | |

| − | ==Minimum wage | + | ===Minimum wage theoretical overview=== |

| − | + | It is important to note that for fundamentalist market economists, any and all attempts to raise wages and conditions of employment above what the unfettered market would provide, are futile and will inevitably deliver less employment and lower welfare for the community at large. This belief has long dominated economists’ labor market policy prescriptions. This is now changing. | |

| − | The | + | The emerging international consensus based on current evidence suggests strongly that it is possible to reduce poverty and improve living standards generally by shaping the labor market with minimum-wage laws, and supplementing these with active training and skill formation policies. |

| − | ==== | + | ====Support of the minimum wage legislation==== |

| − | + | Generally, supporters of the minimum wage claim the following beneficial effects: | |

| − | + | * Increases the average [[standard of living]]. | |

| + | * Creates incentive to work. (Contrast with welfare transfer payments.) | ||

| + | * Does not have budget consequence on government. "Neither taxes nor public sector borrowing requirements rise." Contrast with negative [[income tax]]es such as the [[Earned income tax credit]] (EITC). | ||

| + | * Minimum wage is administratively simple; workers only need to report violations of wages less than minimum, minimizing a need for a large enforcement agency. | ||

| + | * Stimulates consumption, by putting more money in the hands of low-income people who, usually, spend their entire paychecks. | ||

| + | * Increases the [[work ethic]] of those who earn very little, as employers demand more return from the higher cost of hiring these employees. | ||

| + | * Decreases the cost of government social welfare programs by increasing incomes for the lowest-paid. | ||

| + | * Prevents in-work benefits (such as the Earned Income Tax Credit and the [[Working tax credit]]) from causing a reduction in gross wages which would otherwise occur if the labor supply is not perfectly inelastic. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Indeed, it has shown to be appropriate for countries with low levels of GDP per capita, as for instance of [[Brazil]], using a kind of Guaranteed Social Income (GSI) to try to bring millions people out of poverty. The classical example of "social" aspect of minimum wages clashing with free market and pointing out the importance of "know-how" education is seen in almost every single Eastern European and Central Asian (former Communist) country. Under the old regimes everybody "had" to have a work and was paid, mostly "close to minimum wage," for being at that work. Technical education did not make so much difference, in wages, to bother, so nobody bothered and, indeed, the whole Communist system dissolved via economics. Nowadays, there are highly technical workers needed but they are in short supply. Pensions are low, unemployment high, and it should not surprise anybody when most of ordinary workers mentions that they had a better standard of living under Communists. | ||

| − | + | This is in agreement with the alternate view of the labor market that has low-wage labor markets characterized as [[monopsonistic competition]] wherein buyers (employers) have significantly more [[market power]] than do sellers (workers). Such a case is a type of [[market failure]]—always seen as a major shortcoming of any Communist economy—and results in workers being paid less than their marginal value. Under the [[Monopsony|monoposonistic]] assumption, an appropriately set minimum wage could increase both [[wages]] and [[employment]], with the optimal level being equal to the [[marginal productivity]] of labor.<ref>Alan Manning, ''Monopsony in Motion: Imperfect Competition in Labor Markets'' (Princeton University Press, 2003). </ref> | |

| − | + | This view emphasizes the role of minimum wages as a [[regulated market|market regulation]] policy akin to [[antitrust]] policies, as opposed to an illusory "[[free lunch]]" for low-wage workers. | |

| − | |||

| − | The | + | ====Voices from the opposite camp==== |

| + | Five excerpts, from very different academics and writers who have researched this topic provide a contrasting perspective: | ||

| + | <blockquote>The estimation in which different qualities of labour are held comes soon to be adjusted in the market with suffi cient precision for all practical purposes, and depends much on the comparative skill of the laborer and the intensity of the labor performed. The scale, when once formed, is liable to little variation. If a day’s labor of a working jeweller be more valuable than a day’s labor of a common laborer, it has long ago been adjusted and placed in its proper position in the scale of value.<ref> David Ricardo, ''The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation'' (Dover Publications, 2004, ISBN 978-0486434612).</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | <blockquote>The higher the minimum wage, the greater will be the number of covered workers who are discharged.<ref>George J. Stigler, "The economics of minimum wage legislation" ''American Economic Review'' 36 (1946): 358-365.</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | + | <blockquote>In a background paper for ''Canadian Policy Research Networks’ Vulnerable Workers Series,'' we asked the author, [[Olalekan Edagbami]], to disregard the outliers (studies that find extreme results, at either end of the spectrum) and focus on what the preponderance of research says about minimum-wage increases. His conclusion: "There is evidence of a significant negative impact on teenage employment, a smaller negative impact on young adults and little or no evidence of a negative impact on employment for workers aged 25 or older."<ref>Ron Saunders, "Should We Jack Up Minimum Wage?" ''Toronto Star'', 2007.</ref></blockquote> | |

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>Minimum wages often hurt those they are designed to help. What good does it do unskilled youth to know that an employer must pay them $3.35 per hour if that fact is what keeps them from getting jobs?<ref>P.A. Samuelson and W. Nordhaus, ''Economics'' (New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 2004, ISBN 978-0072872057).</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | <blockquote>The whole point of a minimum wage is that the market wage for some workers—the wage that would just balance the supply of and demand for unskilled, transient, or young workers in highly unstable service industries—is deemed to be too low. If, accordingly, it is fixed by law above the market level, it must be at a point where the supply exceeds the demand. Economists have a technical term for that gap. It’s called "unemployment." …The point is not that those struggling to get by on very low wages should be left to their own devices. The point is that wages, properly considered, are neither the instrument nor the objective of a just society. When we say their wages are “too low,” we mean in terms of what society believes is decent. But that’s not what wages are for. The point of a wage, like any other price, is to ensure every seller finds a willing buyer and vice versa, without giving rise to shortages or surpluses—not to attempt to reflect broader social notions of what is appropriate. That's especially true when employers can always sidestep any attempt to impose a “just” wage simply by hiring fewer workers.<ref>A. Coyne, "The injustice of the minimum wage." In ''National Post'', 2007.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Thus, opponents of the minimum wage claim it has these and other effects: | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Hurts small business more than large business.<ref>[http://www.pressherald.com/2016/08/11/maine-voices-raising-minimum-wage-will-hurt-small-businesses-and-increase-layoffs/ Maine Voices: Raising minimum wage will hurt small businesses and increase layoffs] ''Portland Press Herald'', August 11, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2017.</ref> | ||

| + | * Lowers competitiveness<ref>Tim Kane, [http://www.heritage.org/Research/Labor/wm899.cfm Wal-Mart's Perverse Strategy on the Minimum Wage,] ''The Heritage Foundation'', 2005. Retrieved January 11, 2017.</ref> | ||

| + | * Reduces quantity demanded of workers. This may manifest itself through a reduction in the number of hours worked by individuals, or through a reduction in the number of jobs.<ref>Marian L. Tupy, [http://www.nationalreview.com/article/210652/minimum-interference-marian-l-tupy Minimum Interference,] ''National Review Online,'' May 14, 2004. Retrieved January 11, 2017.</ref> | ||

| + | * Hurts the least employable by making them unemployable, in effect pricing them out of the market.<ref name=kibbe>Matthew B. Kibbe, [http://www.cato.org/pubs/pas/pa106.html The Minimum Wage: Washington's Perennial Myth,] ''Cato Institute Policy Analysis No. 106'', May 23, 1988. Retrieved January 11, 2017.</ref> | ||

| + | * Increases prices for customers of employers of minimum wage workers, which would pass through to the general price level,<ref>Daniel Aaronson and Eric, French, [https://www.epionline.org/studies/r100/ Output Prices and the Minimum Wage,] ''Employment Policies Institute.'' June, 2006. Retrieved January 11, 2017.</ref> | ||

| + | * Does not improve the situation of those in [[poverty]]. "Will have only negative effects on the distribution of [[economic justice]]. Minimum-wage legislation, by its very nature, benefits some at the expense of the least experienced, least productive, and poorest workers."<ref name=kibbe/> | ||

| + | * Increases the number of people on welfare, thus requiring greater government spending.<ref name=case>Joint Economic Committee Republicans, [http://www.jec.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/e6663010-d095-4db8-9cb9-ae64da9fa165/the-case-against-a-higher-minimum-wage---may-1996.pdf The Case Against a Higher Minimum Wage.] May, 1996, Retrieved January 11, 2017.</ref> | ||

| + | * Encourages high school students to drop-out.<ref name=case/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==The economic effects of minimum-wage laws== | ||

| + | Simply stated, if the government coercively raises the [[price]] of some item (such as [[labor]]) above its [[market]] value, the demand for that item will fall, and some of the [[supply]] will become "disemployed." Unfortunately, in the case of minimum wages, the dis-employed goods are human beings. The worker who is not quite worth the newly imposed price loses out. Typically, the losers include young workers who have too little experience to be worth the new minimum and marginal workers who, for whatever reason, cannot produce very much. First and foremost, minimum-wage legislation hurts the least employable by making them unemployable, in effect pricing them out of the market. | ||

| + | |||

| + | An individual will not be hired at $5.05 an hour if an employer feels that he is unlikely to produce at least that much value for the firm. This is common business sense. Thus, individuals whom employers perceive to be incapable of producing value at the arbitrarily set minimum rate are not hired at all, and people who could have been employed at market wages are put on the street.<ref name=kibbe/> | ||

| + | |||

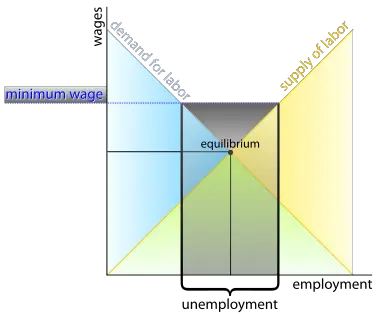

| + | ===Supply of labor curve=== | ||

| + | The amount of labor that workers supply is generally considered to be positively related to the nominal wage; as wage increases, labor supplied increases. Economists graph this relationship with the wage on the vertical axis and the labor on the horizontal axis. The supply of labor curve then is upward sloping, and is depicted as a line moving up and to the right. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The upward sloping labor supply curve is based on the assumption that at low wages workers prefer to consume [[leisure]] and forgo wages. As nominal wages increase, choosing leisure over labor becomes more expensive, and so workers supply more labor. Graphically, this is shown by movement along the labor supply curve, that is, the curve itself does not move. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Other variables, such as price, may cause the labor supply curve to shift, such that an increase in the price level may cause workers to supply less labor at all wages. This is depicted graphically by a shift of the entire curve to the left. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===The Iron Law of Wages: Malthus=== | ||

| + | According to the [[Thomas Robert Malthus|Malthusian]] theory of population, the size of population will grow very rapidly whenever wages rise above the subsistence level (the minimal level needed to support a person’s life). In this theory, the labor supply curve should be horizontal at the subsistence wage level, which is sometimes called the "Iron Law of Wages." In the graph below, the "subsistence wage level" could be depicted by a horizontal straight edge that would be set anywhere below the equilibrium point on the Y (wage)-axis. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Malthus’ gloomy doctrine exerted a powerful impact upon social reformers of the nineteenth century, for this view predicted that any improvement in the living standards of the working classes would be eaten up by population increase. | ||

| + | <blockquote>Looking at the statistics of Europe and North America, we see that the people do not inevitably reproduce so rapidly—if at all—but the effect of globalization might eventually simulate such a tendency and, perhaps there is a germ of truth in Malthus’ views for the poorest countries today.<ref name=Samuelson>P.A. Samuelson and W.D. Nordhaus, ''Micro-Economics'' (New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 2001, ISBN 978-0072314908).</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===The reserve army of the unemployed: Marx=== | ||

| + | [[Karl Marx]] devised quite a different version of the iron law of wages. He put great emphasis upon the “reserve army of unemployed.” In effect, employers led their workers to the factory windows and pointed to the unemployed workers outside, eager to work for less. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>This, Marx is interpreted to have thought, would depress wages to the subsistence level. Again, in a competitive labor market, the reserve army can depress wages only to equilibrium level. Only if labor supply became so abundant and demand were in equilibrium at minimum-subsistence level, the wage would be at a minimum level, as in many underdeveloped countries.<ref name=Samuelson/></blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Demand for labor curve=== | ||

| + | The amount of labor demanded by firms is generally assumed to be negatively related to the nominal wage; as wages increase, firms demand less labor. As with the supply of labor curve, this relationship is often depicted on a graph with wages represented on the vertical axis, and labor on the horizontal axis. The demand for labor curve is downward sloping, and is depicted as a line moving down and to the right on a graph. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The downward sloping demand for labor curve is based on the assumption that firms are profit maximizers. That means they seek the level of production that maximizes the difference between revenue and costs. A firm's revenue is based on the price of its goods, and the number of goods it sells. Its cost, in terms of labor, is based on the wage. Typically, as more workers are added, each additional worker at some point becomes less productive. That is like saying there are too many cooks in the kitchen. Firms therefore only hire an additional worker, who may be less productive than the previous worker, if the wage is no greater than the productivity of that worker times the price. Since productivity decreases with additional workers, firms will only demand more labor at lower wages. Graphically, the effect of a change in is wage is depicted as movement along the demand for labor curve. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Other variables, such as price, may cause the labor demand curve to shift, thus, an increase in the price level may cause firms to increase labor demanded at all wages, because it becomes more profitable to them. This is depicted graphically by a shift in the labor demand curve to the right. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Supply and demand for labor=== | ||

[[Image:Wage labour.svg|Graph of Labor Market|right|380px]] | [[Image:Wage labour.svg|Graph of Labor Market|right|380px]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | Because both the demand for labor curve and the supply of labor curve can be graphed with wages on the vertical axis and labor on the horizontal axis, they can be graphed together. Doing so allows people to examine the possible effects of the minimum wage. | |

| − | + | The point at which the demand for labor curve and the supply of labor curve intersect is the point of equilibrium. Only at that wage will the demand for labor and the supply of labor at the prevailing wage be equal to each other. If the wages are higher than the equilibrium point, then there will be an excess supply of labor, which is [[unemployment]]. | |

| − | + | A minimum wage prevents firms from hiring workers below a certain wage. If that wage is above the equilibrium wage, then, according to this model, there will be an excess of labor supplied, resulting in increased unemployment. Additionally, firms will hire fewer workers than they otherwise would have, so there is also a reduction in employment. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Who benefits== | |

| + | [[Labor union]]s and their members are the most obvious beneficiaries of government-imposed minimum wages. As the established elite of the workforce, union members are on the receiving end of the minimum wage's redistribution process. To fully understand how unions gain from minimum wage legislation, one must consider the essential nature of unions. | ||

| − | + | The success of a union depends on its ability to maintain higher-than-market wages and provide secure jobs for its members. If it cannot offer the benefit of higher wages, a union will quickly lose its members. Higher wages can be obtained only by excluding some workers from the relevant labor markets. As [[F.A. Hayek]] has pointed out: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>Unions have not achieved their present magnitude and power by merely achieving the right of association. They have become what they are largely in consequence of the grant, by legislation and jurisdiction, of unique privileges which no other associations or individuals enjoy.<ref>F.A. Hayek, "Unions, Inflation and Profits." In ''Studies in Philosophy, Politics and Economics'' (Simon and Schuster, New York, 1969. </ref></blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Teenagers and the “Minimum wage legislation”== | |

| − | + | The minimum wage legislation has, historically, been targeting teenage labor force under the assumption that increase of employment in this demographic sector with skill formation (educational attainment and on-the-job training) would benefit the economy. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Economic theory, however, suggests that teens bear most of the dis-employment effects resulting from a minimum wage hike, compared with any other demographic group (for example, adult males), since minimum wages directly affect a high proportion of employed teens. Thus, a great deal of the research examines the economic impact an increase in the minimum wage would have on teenagers. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===American example=== |

| − | + | In the U.S., in 1981, the congressionally-mandated Minimum Wage Study Commission concluded that a 10 percent increase in the minimum wage reduced teenage employment by 1 percent to 3 percent. This estimate was confirmed in more recent studies by David Neumark of Michigan State and William Wascher of the Federal Reserve Board, Kevin Murphy of the University of Chicago, and Donald Deere and Finis Welch of Texas A&M. | |

| − | + | Challenging the widespread view among economists, that an increase in the minimum wage will reduce jobs, is the recent work of economists [[David Card]] and [[Alan Krueger]], both of Princeton. Their studies of fast food restaurant employment after New Jersey and California increased their state minimum wages found no evidence of job loss. However, there appeared to be serious flaws in the data that cast even more serious doubt upon the validity of the [[Card-Krueger]] conclusions. In a paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, Neumark and Wascher reexamined their data, which originally came from telephone surveys. Using actual payroll records from a sample of the same New Jersey and Pennsylvania restaurants, Neumark and Wascher concluded that employment had not risen after an increase in the minimum wage, as Card and Krueger had claimed, but "in fact had fallen."<ref>D. Neumark and W. Wascher, "Do Minimum Wages Fight Poverty?" In NBER Working Paper 6127, 1996. Committee on Small Business, U.S. House of Representatives, the Hon. Jan Meyers, Chair. </ref> A review of the Card study of employment in California by Lowell Taylor of Carnegie Mellon University found that the state minimum wage increase had a major negative effect in low-wage counties and for retail establishments generally. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Thus, [[Nobel Prize]] winning economist [[Gary Becker]] of the University of Chicago concluded that: | |

| − | [[ | + | <blockquote>the Card-Krueger studies are flawed and cannot justify going against the accumulated evidence from many past and present studies that find sizable negative effects of higher minimums on employment.<ref name=Bartlett>Bruce R. Bartlett, "The Impact of Federal Minimum Wage Increase on Small Business.” Committee on Small Business, U.S. House of Representatives, the Hon. Jan Meyers, Chair, 1996. </ref></blockquote> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Even if the minimum wage had no effect on overall employment, there have still been strong arguments voiced against raising it. | |

| − | + | First, it is important to understand that the impact of the minimum wage is not uniform. For 98.2 percent of wage and salary workers, there is no impact at all, because they either already earn more than the minimum or are not covered by it. | |

| − | + | However, for workers in low-wage industries, those without skills, members of minority groups, and those living in areas of the country where wages tend to be lower, the impact can be severe. This is why in the United States economists have found that the primary impact of the minimum wage has been on black teenagers. | |

| − | + | In 1948, when the minimum wage covered a much smaller portion of the labor force, the unemployment rate for black males age 16 and 17 was just 9.4 percent, while the comparable unemployment rate for whites was 10.2 percent. In 1995, unemployment among black teenage males was 37.1 percent, while the unemployment rate for white teenage males was 15.6 percent. The unemployment rate for black teenage males has tended to rise and fall with changes in the real minimum wage. | |

| − | + | ||

| + | Current unemployment is just a part of the long-term price that teenagers of all races pay for the minimum wage. A number of studies have shown that increases in the minimum wage lead employers to cut back on work hours and training. When combined with the loss of job opportunities, this means that many youths, especially minority youth, are prevented from reaching the first rung on the ladder of success, with consequences that can last a lifetime. This may be the worst effect that the minimum wage has. For example, in 1992 former Senator [[George McGovern]] wrote in the ''Los Angeles Times:'' | ||

| − | In the | + | <blockquote>Unfortunately, many entry-level jobs are being phased out as employment costs grow faster than productivity. In that situation, employers are pressured to replace marginal employees with self-service or automation or to eliminate the service altogether. When these jobs disappear, where will young people and those with minimal skills get a start in learning the "invisible curriculum" we all learn on the job? The inexperienced applicant cannot learn about work without a job.<ref name=Bartlett/></blockquote> |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ===OECD experience=== | |

| + | In the research article of Grant Belchamber there is a table “Minimum wages and employment/population ratios—Selected countries” that summarizes the OECD countries’ experience with the minimum wages legislated in selected countries in the “teenagers” demographic categories.<ref>Grant Belchamber, "Minimum Wages and Youth Employment," Australian Council of Trade Union, 2004.</ref><ref>Francine D. Blau and Lawrence M. Kahn, ''At Home and Abroad: U.S. Labor-Market Performance in International Perspective'' (New York: Sage Foundation, 2002, ISBN 978-0871541000).</ref> Their major findings are summarized in Table 1. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The line comparisons below show that—with one exception, that looks like a huge outlier, of the [[Netherlands]]—the standard economic doctrine of the Minimum wage legislation's negative (or, at best, ambiguous) effect on youth employment still holds. | ||

| − | + | '''Table 1''' | |

| + | {| border=1 cellpadding=4 | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |colspan=5|Youth Minimum Wage as Percentage of Adult Minimum Wage in 2002 | ||

| + | |colspan=2|Youth Employment to Population Ratio | ||

| + | |---- | ||

| + | |Country | ||

| + | |Age 16 | ||

| + | |Age 17 | ||

| + | |Age 18 | ||

| + | |Age 19 | ||

| + | |Age 20 | ||

| + | |1990 | ||

| + | |2002 | ||

| + | |---- | ||

| + | |Australia | ||

| + | |50 | ||

| + | |60 | ||

| + | |70 | ||

| + | |80 | ||

| + | |90 | ||

| + | |61.1 | ||

| + | |59.6 | ||

| + | |---- | ||

| + | |Belgium | ||

| + | |70 | ||

| + | |76 | ||

| + | |82 | ||

| + | |88 | ||

| + | |94 | ||

| + | |30.4 | ||

| + | |28.5 | ||

| + | |---- | ||

| + | |Canada | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |61.1 | ||

| + | |57.3 | ||

| + | |---- | ||

| + | |France | ||

| + | ||80 | ||

| + | |90 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |29.5 | ||

| + | |24.1 | ||

| + | |---- | ||

| + | |Greece | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |30.3 | ||

| + | |27.1 | ||

| + | |---- | ||

| + | |Ireland | ||

| + | |70 | ||

| + | |70 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |41.4 | ||

| + | |45.3 | ||

| + | |---- | ||

| + | |Netherlands | ||

| + | |34.5 | ||

| + | |39.5 | ||

| + | |45.5 | ||

| + | |54.5 | ||

| + | |63.5 | ||

| + | |53.0 | ||

| + | |70.5 | ||

| + | |---- | ||

| + | |New Zealand | ||

| + | |80 | ||

| + | |80 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |58.3 | ||

| + | |56.8 | ||

| + | |---- | ||

| + | |Portugal | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |54.8 | ||

| + | |41.9 | ||

| + | |---- | ||

| + | |Spain | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |38.3 | ||

| + | |36.6 | ||

| + | |---- | ||

| + | |UK | ||

| + | |Exempt | ||

| + | |85 | ||

| + | |85 | ||

| + | |85 | ||

| + | |N/A | ||

| + | |70.1 | ||

| + | |61.0 | ||

| + | |---- | ||

| + | |USA | ||

| + | |82.3 | ||

| + | |82.3 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |100 | ||

| + | |59.8 | ||

| + | |55.7 | ||

| + | |---- | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | + | The "outlier" case of the Netherlands, however, offers some very interesting information on this subject. It looks like some explanation might stem from the fact that over the past two decades the Netherlands has instituted and revamped the array of active labor market programs that apply in its labor markets, through its Foundation of Labor and Social-Economic Council. The Dutch initiatives exhibit deep integration between training and skills formation and employment. Perhaps this is the way to go in any country that has a will to solve the problem. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Conclusion== | |

| + | [[Image:Min_wage_low_education.gif|thumb|300px|right|Comparison of the minimum wage to unemployment among low skill workers in the U.S. The two lowest points are for the years 1999 and 2000. Unemployment for all workers in those two years was the lowest since 1970. The data show a correlation in this [[data set]] between the level of the minimum wage and unemployment among lower-educated workers.]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Min_wage_high_education.gif|thumb|300px|right|Comparison of the minimum wage to unemployment among college educated workers in the U.S. In this data set, there is essentially no correlation between the minimum wage and unemployment among higher-educated workers.]] | ||

| − | + | A simple [[classical economics|classical economic]] analysis of [[supply and demand]] implies that by mandating a price floor above the equilibrium wage, minimum wage laws should cause [[unemployment]]. This is because a greater number of workers are willing to work at the higher wage while a smaller numbers of jobs will be available at the higher wage. Companies can be more selective in who they employ thus the least skilled and unexperienced will typically get excluded. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Economically speaking, the theory of supply and demand suggests that the imposition of an artificial value on wages that is higher than the value that would be dictated in a free-market system creates an inefficient market and leads to unemployment. The inefficiency occurs when there are a greater number of workers that want the higher paying jobs than there are employers willing to pay the higher wages. Critics disagree. | |

| − | + | What is generally agreed upon by all parties is that the number of individuals relying on the minimum wage in the United States is less than 5 percent. However, this statistic is largely ignored in favor of citations regarding the number of people that live in poverty. Keep in mind that earning more than minimum wage does not necessary mean that one is not living in poverty. According to estimates from the ''CIA World Fact Book,'' some 13 percent of the U.S. population lives in [[poverty]]. That is 37 million people. | |

| − | + | There are no easy answers towards the “minimum wage legislation” topic. Statistics can be gathered to support both sides of the argument. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | While there are no easy answers, a good first step is to frame the debate in realistic terms. Referring to the minimum wage as a wage designed to support a family confuses the issue. Families need a living wage, not a minimum wage. With that said, working at McDonald's or the local gas station is not a career. These are jobs designed to help entry-level workers join the workforce, not to support the financial needs of a family. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | On the core issue of minimum wage itself, political wrangling is unlikely to result in a real solution. A more practical solution is the following scenario. Young people join the workforce at the low end of the wage scale, build their skills, get an education and move up the ladder to a better paying job, just as members of the workforce have done for generations. The Dutch example seems, in this area, to have achieved two major results: | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | *To prove the economic argument presented in excerpts from various academics (including several Nobel laureates) that the simplistic attitude of the “minimum wage legislation” will never work anywhere. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | * | + | *To point towards a more complex solution than the simple legislative “orders of a minimum wage level.” Such a solution would have to carve—and to “keep maintaining and increasing”—the partnership between the young job seekers and employers based on a system of [[education]] and “know-how” learning with feed-back through which the teenagers, who are “willing” to join the general work-force, could obtain the skills (underwritten financially by the governments) assuring the good living standards for them and, later, for their families. |

| − | * [[ | + | |

| − | + | Hence, the emerging international consensus based on current evidence suggests strongly that it is possible to reduce poverty and improve living standards generally by shaping the labor market with minimum-wage laws, and supplementing these with active training and skill formation policies. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| + | <references/> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | *American Academy of Political and Social Science. ''The Cost of Living''. Philadelphia, 1913. | |

| + | *Bartlett, Bruce R. "The Impact of Federal Minimum Wage Increase on Small Business.” Committee on Small Business, U.S. House of Representatives, the Hon. Jan Meyers, Chair, 1996. | ||

| + | *Belchamber, Grant. ''Minimum Wages and Youth Employment''. Australian Council of Trade Union, 2004. | ||

| + | *Bethell, Leslie. ''The Cambridge History of Latin America''. Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 0521245184 | ||

| + | *Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn. ''At Home and Abroad: U.S. Labor-Market Performance in International Perspective''. New York: Sage Foundation, 2002. ISBN 978-0871541000 | ||

| + | *Coyne, A. "The injustice of the minimum wage." In ''National Post'', 2007. | ||

| + | *Ehrenberg, Ronald G. ''Labor Markets and Integrating National Economies''. Brookings Institution Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0815722571 | ||

| + | *Hayek, F.A. ''Studies in Philosophy, Politics and Economics Simon and Schuster''. New York, 1969. ISBN 978-0671202460 | ||

| + | *Kibbe, Matthew B. ''The Minimum Wage: Washington's Perennial Myth''. Cato Policy Analysis No. 106, 1988. | ||

| + | *Manning, Alan. ''Monopsony in Motion: Imperfect Competition in Labor Markets''. Princeton University Press, 2003. | ||

| + | *Neumark, D., and W. Wascher. "Do Minimum Wages Fight Poverty?" In ''NBER Working Paper 6127'', 1996. Committee on Small Business, U.S. House of Representatives, the Hon. Jan Meyers, Chair. | ||

| + | *OECD Employment Outlook. "At Home and Abroad, Geneva." In ''UK Low Pay Commission Reports'', 2002. | ||

| + | *Ricardo, David. ''The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation''. Dover Publications, 2004. ISBN 978-0486434612 | ||

| + | *Samuelson, P.A., and W. Nordhaus. ''Economics''. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 2004. ISBN 978-0072872057 | ||

| + | *Samuelson, P.A., and W.D. Nordhaus. ''Micro-Economics''. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 2001. ISBN 978-0072314908 | ||

| + | *Saunders, Ron. "Should We Jack Up Minimum Wage?" In ''Toronto Star'', 2007. | ||

| + | *Stigler, George J. "The economics of minimum wage legislation." In ''American Economic Review''. 36 (1946): 358-365. | ||

| + | *Waltman, Jerold.''The Politics of the Minimum Wage.'' University of Illinois Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0252025457 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved November 9, 2022. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | *[http://www.bls.gov/cps/minwage2005.htm Characteristics of Minimum Wage Workers: 2005] U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics | ||

| + | *[http://www.pkarchive.org/cranks/LivingWage.html Economist Paul Krugman on Minimum Wage Regulation] | ||

| + | *[http://www.dol.gov/dol/topic/wages/minimumwage.htm Minimum Wage] U.S. Department of Labor | ||

| + | *[http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20070603164510/http://www.dti.gov.uk/employment/pay/national-minimum-wage/History-National-Minimum-Wage/page12572.html History of the National Minimum Wage] Department of Trade and Industry. | ||

| + | *[http://www.lowpay.gov.uk National Minimum Wage] Low Pay Commission in the United Kingdom | ||

{{Credits|Minimum_wage|156016500|}} | {{Credits|Minimum_wage|156016500|}} | ||

Latest revision as of 18:50, 9 November 2022

Minimum wage is the minimum amount of compensation an employee must receive for performing labor; usually calculated per hour. Minimum wages are typically established by contract, collective bargaining, or legislation by the government. Thus, it is illegal to pay an employee less than the minimum wage. Employers may pay employees by some other method than hourly, such as by piecework or commission; the rate when calculated on an hourly basis must equal at least the current minimum wage per hour.

The intent of minimum wage legislation is to to avoid exploitation of workers and ensure that all members in the society who put in legitimate time at work are compensated at a rate that allows them to live within that society with adequate food, housing, clothes, and other essentials. Such intent reflects the emerging human consciousness of human rights and the desire for a world of harmony and prosperity for all. Both economic theory and practice, however, suggest that mandating a minimum monetary compensation for work performed is not sufficient by itself to guarantee improvements in the quality of life of all members of society.

Definition

The minimum wage is defined as the minimum compensation that an employee must receive for their labor. For an employer to pay less is illegal and subject to penalties. The minimum wage is established by government legislation or collective bargaining.

For example, in the United States, the minimum wage for eligible employees under Federal law is $7.25 per hour, effective July 24, 2009. Many states also have minimum wage laws, which guarantee a higher minimum wage.

Historical and theoretical overview

In defending and advancing the interests of ordinary working people, trade unions seek to raise wages and improve working conditions, and thus to raise the human condition in society generally. This quest has sustained and motivated unionists for the better part of 200 years.

Many supporters of the minimum wage assert that it is a matter of social justice that helps reduce exploitation and ensures workers can afford what they consider to be basic necessities.

Historical roots

In 1896, New Zealand established arbitration boards with the Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act).[1] Also in 1896, in Victoria, Australia, an amendment to the Factories Act provided for the creation of a wages board.[1] The wages board did not set a universal minimum wage, but set basic wages for six industries that were considered to pay low wages.

Legally, a minimum wage being the lowest hourly, daily, or monthly wage that employers may pay to employees or workers, was first enacted in Australia via the 1907 “Harvester judgment” which made reference to basic wages. The Harvester judgment was the first attempt at establishing a wage based upon needs, below which no worker should be expected to live.

Also in 1907, Ernest Aves was sent by the British Secretary of State for the Home Department to investigate the results of the minimum wage laws in Australia and New Zealand. In part as a result of his report, Winston Churchill, then president of the Board of Trade, introduced the Trade Boards Act on March 24, 1909, establishing trade boards to set minimum wage rates in certain industries. It became law in October of that year, and went into effect in January 1911.

Massachusetts passed the first state minimum wage law in 1912, after a committee had shown the nation that women and children were working long hours at wages barely sufficient to maintain a meager existence. By 1923, 17 states had adopted minimum wage legislation mainly for women and minors in a variety of industries and occupations.

In the United States, statutory minimum wages were first introduced nationally in 1938.[2] In addition to the federal minimum wage, nearly all states within the United States have their own minimum wage laws with the exception of South Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana.[3]

In the 1960s, minimum wage laws were introduced into Latin America as part of the Alliance for Progress; however these minimum wages were, and are, low.

In the European Union, 22 out of 28 member states had national minimum wages as of 2016.[4] Northern manufacturing firms lobbied for the minimum wage so as to prevent firms located in the south, where labor was cheaper, from competing. Many countries, such as Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Italy, and Cyprus have no minimum wage laws, but rely on employer groups and trade unions to set minimum earnings through collective bargaining.[5]

The International Labour Office in Geneva, Switzerland reports that some 90 percent of countries around the world have legislation supporting a minimum wage. The minimum wage in countries that rank within the lowest 20 percent of the pay scale is less than $2 per day, or about $57 per month. The minimum wage in the countries that represent the highest 20 percent of the pay scale is about $40 per day, or about $1,185 per month.

Minimum wage theoretical overview

It is important to note that for fundamentalist market economists, any and all attempts to raise wages and conditions of employment above what the unfettered market would provide, are futile and will inevitably deliver less employment and lower welfare for the community at large. This belief has long dominated economists’ labor market policy prescriptions. This is now changing.

The emerging international consensus based on current evidence suggests strongly that it is possible to reduce poverty and improve living standards generally by shaping the labor market with minimum-wage laws, and supplementing these with active training and skill formation policies.

Support of the minimum wage legislation

Generally, supporters of the minimum wage claim the following beneficial effects:

- Increases the average standard of living.

- Creates incentive to work. (Contrast with welfare transfer payments.)

- Does not have budget consequence on government. "Neither taxes nor public sector borrowing requirements rise." Contrast with negative income taxes such as the Earned income tax credit (EITC).

- Minimum wage is administratively simple; workers only need to report violations of wages less than minimum, minimizing a need for a large enforcement agency.

- Stimulates consumption, by putting more money in the hands of low-income people who, usually, spend their entire paychecks.

- Increases the work ethic of those who earn very little, as employers demand more return from the higher cost of hiring these employees.

- Decreases the cost of government social welfare programs by increasing incomes for the lowest-paid.

- Prevents in-work benefits (such as the Earned Income Tax Credit and the Working tax credit) from causing a reduction in gross wages which would otherwise occur if the labor supply is not perfectly inelastic.

Indeed, it has shown to be appropriate for countries with low levels of GDP per capita, as for instance of Brazil, using a kind of Guaranteed Social Income (GSI) to try to bring millions people out of poverty. The classical example of "social" aspect of minimum wages clashing with free market and pointing out the importance of "know-how" education is seen in almost every single Eastern European and Central Asian (former Communist) country. Under the old regimes everybody "had" to have a work and was paid, mostly "close to minimum wage," for being at that work. Technical education did not make so much difference, in wages, to bother, so nobody bothered and, indeed, the whole Communist system dissolved via economics. Nowadays, there are highly technical workers needed but they are in short supply. Pensions are low, unemployment high, and it should not surprise anybody when most of ordinary workers mentions that they had a better standard of living under Communists.

This is in agreement with the alternate view of the labor market that has low-wage labor markets characterized as monopsonistic competition wherein buyers (employers) have significantly more market power than do sellers (workers). Such a case is a type of market failure—always seen as a major shortcoming of any Communist economy—and results in workers being paid less than their marginal value. Under the monoposonistic assumption, an appropriately set minimum wage could increase both wages and employment, with the optimal level being equal to the marginal productivity of labor.[6]

This view emphasizes the role of minimum wages as a market regulation policy akin to antitrust policies, as opposed to an illusory "free lunch" for low-wage workers.

Voices from the opposite camp

Five excerpts, from very different academics and writers who have researched this topic provide a contrasting perspective:

The estimation in which different qualities of labour are held comes soon to be adjusted in the market with suffi cient precision for all practical purposes, and depends much on the comparative skill of the laborer and the intensity of the labor performed. The scale, when once formed, is liable to little variation. If a day’s labor of a working jeweller be more valuable than a day’s labor of a common laborer, it has long ago been adjusted and placed in its proper position in the scale of value.[7]

The higher the minimum wage, the greater will be the number of covered workers who are discharged.[8]

In a background paper for Canadian Policy Research Networks’ Vulnerable Workers Series, we asked the author, Olalekan Edagbami, to disregard the outliers (studies that find extreme results, at either end of the spectrum) and focus on what the preponderance of research says about minimum-wage increases. His conclusion: "There is evidence of a significant negative impact on teenage employment, a smaller negative impact on young adults and little or no evidence of a negative impact on employment for workers aged 25 or older."[9]

Minimum wages often hurt those they are designed to help. What good does it do unskilled youth to know that an employer must pay them $3.35 per hour if that fact is what keeps them from getting jobs?[10]

The whole point of a minimum wage is that the market wage for some workers—the wage that would just balance the supply of and demand for unskilled, transient, or young workers in highly unstable service industries—is deemed to be too low. If, accordingly, it is fixed by law above the market level, it must be at a point where the supply exceeds the demand. Economists have a technical term for that gap. It’s called "unemployment." …The point is not that those struggling to get by on very low wages should be left to their own devices. The point is that wages, properly considered, are neither the instrument nor the objective of a just society. When we say their wages are “too low,” we mean in terms of what society believes is decent. But that’s not what wages are for. The point of a wage, like any other price, is to ensure every seller finds a willing buyer and vice versa, without giving rise to shortages or surpluses—not to attempt to reflect broader social notions of what is appropriate. That's especially true when employers can always sidestep any attempt to impose a “just” wage simply by hiring fewer workers.[11]

Thus, opponents of the minimum wage claim it has these and other effects:

- Hurts small business more than large business.[12]

- Lowers competitiveness[13]

- Reduces quantity demanded of workers. This may manifest itself through a reduction in the number of hours worked by individuals, or through a reduction in the number of jobs.[14]

- Hurts the least employable by making them unemployable, in effect pricing them out of the market.[15]

- Increases prices for customers of employers of minimum wage workers, which would pass through to the general price level,[16]

- Does not improve the situation of those in poverty. "Will have only negative effects on the distribution of economic justice. Minimum-wage legislation, by its very nature, benefits some at the expense of the least experienced, least productive, and poorest workers."[15]

- Increases the number of people on welfare, thus requiring greater government spending.[17]

- Encourages high school students to drop-out.[17]

The economic effects of minimum-wage laws

Simply stated, if the government coercively raises the price of some item (such as labor) above its market value, the demand for that item will fall, and some of the supply will become "disemployed." Unfortunately, in the case of minimum wages, the dis-employed goods are human beings. The worker who is not quite worth the newly imposed price loses out. Typically, the losers include young workers who have too little experience to be worth the new minimum and marginal workers who, for whatever reason, cannot produce very much. First and foremost, minimum-wage legislation hurts the least employable by making them unemployable, in effect pricing them out of the market.

An individual will not be hired at $5.05 an hour if an employer feels that he is unlikely to produce at least that much value for the firm. This is common business sense. Thus, individuals whom employers perceive to be incapable of producing value at the arbitrarily set minimum rate are not hired at all, and people who could have been employed at market wages are put on the street.[15]

Supply of labor curve

The amount of labor that workers supply is generally considered to be positively related to the nominal wage; as wage increases, labor supplied increases. Economists graph this relationship with the wage on the vertical axis and the labor on the horizontal axis. The supply of labor curve then is upward sloping, and is depicted as a line moving up and to the right.

The upward sloping labor supply curve is based on the assumption that at low wages workers prefer to consume leisure and forgo wages. As nominal wages increase, choosing leisure over labor becomes more expensive, and so workers supply more labor. Graphically, this is shown by movement along the labor supply curve, that is, the curve itself does not move.

Other variables, such as price, may cause the labor supply curve to shift, such that an increase in the price level may cause workers to supply less labor at all wages. This is depicted graphically by a shift of the entire curve to the left.

The Iron Law of Wages: Malthus

According to the Malthusian theory of population, the size of population will grow very rapidly whenever wages rise above the subsistence level (the minimal level needed to support a person’s life). In this theory, the labor supply curve should be horizontal at the subsistence wage level, which is sometimes called the "Iron Law of Wages." In the graph below, the "subsistence wage level" could be depicted by a horizontal straight edge that would be set anywhere below the equilibrium point on the Y (wage)-axis.

Malthus’ gloomy doctrine exerted a powerful impact upon social reformers of the nineteenth century, for this view predicted that any improvement in the living standards of the working classes would be eaten up by population increase.

Looking at the statistics of Europe and North America, we see that the people do not inevitably reproduce so rapidly—if at all—but the effect of globalization might eventually simulate such a tendency and, perhaps there is a germ of truth in Malthus’ views for the poorest countries today.[18]

The reserve army of the unemployed: Marx

Karl Marx devised quite a different version of the iron law of wages. He put great emphasis upon the “reserve army of unemployed.” In effect, employers led their workers to the factory windows and pointed to the unemployed workers outside, eager to work for less.

This, Marx is interpreted to have thought, would depress wages to the subsistence level. Again, in a competitive labor market, the reserve army can depress wages only to equilibrium level. Only if labor supply became so abundant and demand were in equilibrium at minimum-subsistence level, the wage would be at a minimum level, as in many underdeveloped countries.[18]

Demand for labor curve

The amount of labor demanded by firms is generally assumed to be negatively related to the nominal wage; as wages increase, firms demand less labor. As with the supply of labor curve, this relationship is often depicted on a graph with wages represented on the vertical axis, and labor on the horizontal axis. The demand for labor curve is downward sloping, and is depicted as a line moving down and to the right on a graph.

The downward sloping demand for labor curve is based on the assumption that firms are profit maximizers. That means they seek the level of production that maximizes the difference between revenue and costs. A firm's revenue is based on the price of its goods, and the number of goods it sells. Its cost, in terms of labor, is based on the wage. Typically, as more workers are added, each additional worker at some point becomes less productive. That is like saying there are too many cooks in the kitchen. Firms therefore only hire an additional worker, who may be less productive than the previous worker, if the wage is no greater than the productivity of that worker times the price. Since productivity decreases with additional workers, firms will only demand more labor at lower wages. Graphically, the effect of a change in is wage is depicted as movement along the demand for labor curve.

Other variables, such as price, may cause the labor demand curve to shift, thus, an increase in the price level may cause firms to increase labor demanded at all wages, because it becomes more profitable to them. This is depicted graphically by a shift in the labor demand curve to the right.

Supply and demand for labor

Because both the demand for labor curve and the supply of labor curve can be graphed with wages on the vertical axis and labor on the horizontal axis, they can be graphed together. Doing so allows people to examine the possible effects of the minimum wage.

The point at which the demand for labor curve and the supply of labor curve intersect is the point of equilibrium. Only at that wage will the demand for labor and the supply of labor at the prevailing wage be equal to each other. If the wages are higher than the equilibrium point, then there will be an excess supply of labor, which is unemployment.

A minimum wage prevents firms from hiring workers below a certain wage. If that wage is above the equilibrium wage, then, according to this model, there will be an excess of labor supplied, resulting in increased unemployment. Additionally, firms will hire fewer workers than they otherwise would have, so there is also a reduction in employment.

Who benefits

Labor unions and their members are the most obvious beneficiaries of government-imposed minimum wages. As the established elite of the workforce, union members are on the receiving end of the minimum wage's redistribution process. To fully understand how unions gain from minimum wage legislation, one must consider the essential nature of unions.

The success of a union depends on its ability to maintain higher-than-market wages and provide secure jobs for its members. If it cannot offer the benefit of higher wages, a union will quickly lose its members. Higher wages can be obtained only by excluding some workers from the relevant labor markets. As F.A. Hayek has pointed out:

Unions have not achieved their present magnitude and power by merely achieving the right of association. They have become what they are largely in consequence of the grant, by legislation and jurisdiction, of unique privileges which no other associations or individuals enjoy.[19]

Teenagers and the “Minimum wage legislation”

The minimum wage legislation has, historically, been targeting teenage labor force under the assumption that increase of employment in this demographic sector with skill formation (educational attainment and on-the-job training) would benefit the economy.

Economic theory, however, suggests that teens bear most of the dis-employment effects resulting from a minimum wage hike, compared with any other demographic group (for example, adult males), since minimum wages directly affect a high proportion of employed teens. Thus, a great deal of the research examines the economic impact an increase in the minimum wage would have on teenagers.

American example

In the U.S., in 1981, the congressionally-mandated Minimum Wage Study Commission concluded that a 10 percent increase in the minimum wage reduced teenage employment by 1 percent to 3 percent. This estimate was confirmed in more recent studies by David Neumark of Michigan State and William Wascher of the Federal Reserve Board, Kevin Murphy of the University of Chicago, and Donald Deere and Finis Welch of Texas A&M.

Challenging the widespread view among economists, that an increase in the minimum wage will reduce jobs, is the recent work of economists David Card and Alan Krueger, both of Princeton. Their studies of fast food restaurant employment after New Jersey and California increased their state minimum wages found no evidence of job loss. However, there appeared to be serious flaws in the data that cast even more serious doubt upon the validity of the Card-Krueger conclusions. In a paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, Neumark and Wascher reexamined their data, which originally came from telephone surveys. Using actual payroll records from a sample of the same New Jersey and Pennsylvania restaurants, Neumark and Wascher concluded that employment had not risen after an increase in the minimum wage, as Card and Krueger had claimed, but "in fact had fallen."[20] A review of the Card study of employment in California by Lowell Taylor of Carnegie Mellon University found that the state minimum wage increase had a major negative effect in low-wage counties and for retail establishments generally.

Thus, Nobel Prize winning economist Gary Becker of the University of Chicago concluded that:

the Card-Krueger studies are flawed and cannot justify going against the accumulated evidence from many past and present studies that find sizable negative effects of higher minimums on employment.[21]

Even if the minimum wage had no effect on overall employment, there have still been strong arguments voiced against raising it.

First, it is important to understand that the impact of the minimum wage is not uniform. For 98.2 percent of wage and salary workers, there is no impact at all, because they either already earn more than the minimum or are not covered by it.

However, for workers in low-wage industries, those without skills, members of minority groups, and those living in areas of the country where wages tend to be lower, the impact can be severe. This is why in the United States economists have found that the primary impact of the minimum wage has been on black teenagers.

In 1948, when the minimum wage covered a much smaller portion of the labor force, the unemployment rate for black males age 16 and 17 was just 9.4 percent, while the comparable unemployment rate for whites was 10.2 percent. In 1995, unemployment among black teenage males was 37.1 percent, while the unemployment rate for white teenage males was 15.6 percent. The unemployment rate for black teenage males has tended to rise and fall with changes in the real minimum wage.

Current unemployment is just a part of the long-term price that teenagers of all races pay for the minimum wage. A number of studies have shown that increases in the minimum wage lead employers to cut back on work hours and training. When combined with the loss of job opportunities, this means that many youths, especially minority youth, are prevented from reaching the first rung on the ladder of success, with consequences that can last a lifetime. This may be the worst effect that the minimum wage has. For example, in 1992 former Senator George McGovern wrote in the Los Angeles Times:

Unfortunately, many entry-level jobs are being phased out as employment costs grow faster than productivity. In that situation, employers are pressured to replace marginal employees with self-service or automation or to eliminate the service altogether. When these jobs disappear, where will young people and those with minimal skills get a start in learning the "invisible curriculum" we all learn on the job? The inexperienced applicant cannot learn about work without a job.[21]

OECD experience

In the research article of Grant Belchamber there is a table “Minimum wages and employment/population ratios—Selected countries” that summarizes the OECD countries’ experience with the minimum wages legislated in selected countries in the “teenagers” demographic categories.[22][23] Their major findings are summarized in Table 1.

The line comparisons below show that—with one exception, that looks like a huge outlier, of the Netherlands—the standard economic doctrine of the Minimum wage legislation's negative (or, at best, ambiguous) effect on youth employment still holds.

Table 1

| Youth Minimum Wage as Percentage of Adult Minimum Wage in 2002 | Youth Employment to Population Ratio | ||||||

| Country | Age 16 | Age 17 | Age 18 | Age 19 | Age 20 | 1990 | 2002 |

| Australia | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 61.1 | 59.6 |

| Belgium | 70 | 76 | 82 | 88 | 94 | 30.4 | 28.5 |

| Canada | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 61.1 | 57.3 |

| France | 80 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 29.5 | 24.1 |

| Greece | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 30.3 | 27.1 |

| Ireland | 70 | 70 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 41.4 | 45.3 |

| Netherlands | 34.5 | 39.5 | 45.5 | 54.5 | 63.5 | 53.0 | 70.5 |

| New Zealand | 80 | 80 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 58.3 | 56.8 |

| Portugal | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 54.8 | 41.9 |

| Spain | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 38.3 | 36.6 |

| UK | Exempt | 85 | 85 | 85 | N/A | 70.1 | 61.0 |

| USA | 82.3 | 82.3 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 59.8 | 55.7 |

The "outlier" case of the Netherlands, however, offers some very interesting information on this subject. It looks like some explanation might stem from the fact that over the past two decades the Netherlands has instituted and revamped the array of active labor market programs that apply in its labor markets, through its Foundation of Labor and Social-Economic Council. The Dutch initiatives exhibit deep integration between training and skills formation and employment. Perhaps this is the way to go in any country that has a will to solve the problem.

Conclusion

A simple classical economic analysis of supply and demand implies that by mandating a price floor above the equilibrium wage, minimum wage laws should cause unemployment. This is because a greater number of workers are willing to work at the higher wage while a smaller numbers of jobs will be available at the higher wage. Companies can be more selective in who they employ thus the least skilled and unexperienced will typically get excluded.

Economically speaking, the theory of supply and demand suggests that the imposition of an artificial value on wages that is higher than the value that would be dictated in a free-market system creates an inefficient market and leads to unemployment. The inefficiency occurs when there are a greater number of workers that want the higher paying jobs than there are employers willing to pay the higher wages. Critics disagree.

What is generally agreed upon by all parties is that the number of individuals relying on the minimum wage in the United States is less than 5 percent. However, this statistic is largely ignored in favor of citations regarding the number of people that live in poverty. Keep in mind that earning more than minimum wage does not necessary mean that one is not living in poverty. According to estimates from the CIA World Fact Book, some 13 percent of the U.S. population lives in poverty. That is 37 million people.

There are no easy answers towards the “minimum wage legislation” topic. Statistics can be gathered to support both sides of the argument.

While there are no easy answers, a good first step is to frame the debate in realistic terms. Referring to the minimum wage as a wage designed to support a family confuses the issue. Families need a living wage, not a minimum wage. With that said, working at McDonald's or the local gas station is not a career. These are jobs designed to help entry-level workers join the workforce, not to support the financial needs of a family.

On the core issue of minimum wage itself, political wrangling is unlikely to result in a real solution. A more practical solution is the following scenario. Young people join the workforce at the low end of the wage scale, build their skills, get an education and move up the ladder to a better paying job, just as members of the workforce have done for generations. The Dutch example seems, in this area, to have achieved two major results:

- To prove the economic argument presented in excerpts from various academics (including several Nobel laureates) that the simplistic attitude of the “minimum wage legislation” will never work anywhere.

- To point towards a more complex solution than the simple legislative “orders of a minimum wage level.” Such a solution would have to carve—and to “keep maintaining and increasing”—the partnership between the young job seekers and employers based on a system of education and “know-how” learning with feed-back through which the teenagers, who are “willing” to join the general work-force, could obtain the skills (underwritten financially by the governments) assuring the good living standards for them and, later, for their families.

Hence, the emerging international consensus based on current evidence suggests strongly that it is possible to reduce poverty and improve living standards generally by shaping the labor market with minimum-wage laws, and supplementing these with active training and skill formation policies.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 American Academy of Political and Social Science, The Cost of Living (Philadelphia, 1913).

- ↑ Sanjiv Sachdev, Raising the Rate: An Evaluation of the Uprating Mechanism for the Minimum Wage (Employee Relations, 2003).

- ↑ www.dol.gov, Minimum Wage Laws in the States - January 1, 2017 Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ↑ Karel Fric, Statutory minimum wages in the EU 2016 European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, January 29, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ↑ Ronald G. Ehrenberg, Labor Markets and Integrating National Economies (Brookings Institution Press, 1994), p. 41.

- ↑ Alan Manning, Monopsony in Motion: Imperfect Competition in Labor Markets (Princeton University Press, 2003).

- ↑ David Ricardo, The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (Dover Publications, 2004, ISBN 978-0486434612).

- ↑ George J. Stigler, "The economics of minimum wage legislation" American Economic Review 36 (1946): 358-365.

- ↑ Ron Saunders, "Should We Jack Up Minimum Wage?" Toronto Star, 2007.

- ↑ P.A. Samuelson and W. Nordhaus, Economics (New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 2004, ISBN 978-0072872057).

- ↑ A. Coyne, "The injustice of the minimum wage." In National Post, 2007.

- ↑ Maine Voices: Raising minimum wage will hurt small businesses and increase layoffs Portland Press Herald, August 11, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ↑ Tim Kane, Wal-Mart's Perverse Strategy on the Minimum Wage, The Heritage Foundation, 2005. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ↑ Marian L. Tupy, Minimum Interference, National Review Online, May 14, 2004. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Matthew B. Kibbe, The Minimum Wage: Washington's Perennial Myth, Cato Institute Policy Analysis No. 106, May 23, 1988. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ↑ Daniel Aaronson and Eric, French, Output Prices and the Minimum Wage, Employment Policies Institute. June, 2006. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Joint Economic Committee Republicans, The Case Against a Higher Minimum Wage. May, 1996, Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 P.A. Samuelson and W.D. Nordhaus, Micro-Economics (New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 2001, ISBN 978-0072314908).

- ↑ F.A. Hayek, "Unions, Inflation and Profits." In Studies in Philosophy, Politics and Economics (Simon and Schuster, New York, 1969.

- ↑ D. Neumark and W. Wascher, "Do Minimum Wages Fight Poverty?" In NBER Working Paper 6127, 1996. Committee on Small Business, U.S. House of Representatives, the Hon. Jan Meyers, Chair.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Bruce R. Bartlett, "The Impact of Federal Minimum Wage Increase on Small Business.” Committee on Small Business, U.S. House of Representatives, the Hon. Jan Meyers, Chair, 1996.

- ↑ Grant Belchamber, "Minimum Wages and Youth Employment," Australian Council of Trade Union, 2004.

- ↑ Francine D. Blau and Lawrence M. Kahn, At Home and Abroad: U.S. Labor-Market Performance in International Perspective (New York: Sage Foundation, 2002, ISBN 978-0871541000).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- American Academy of Political and Social Science. The Cost of Living. Philadelphia, 1913.

- Bartlett, Bruce R. "The Impact of Federal Minimum Wage Increase on Small Business.” Committee on Small Business, U.S. House of Representatives, the Hon. Jan Meyers, Chair, 1996.

- Belchamber, Grant. Minimum Wages and Youth Employment. Australian Council of Trade Union, 2004.

- Bethell, Leslie. The Cambridge History of Latin America. Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 0521245184

- Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn. At Home and Abroad: U.S. Labor-Market Performance in International Perspective. New York: Sage Foundation, 2002. ISBN 978-0871541000

- Coyne, A. "The injustice of the minimum wage." In National Post, 2007.

- Ehrenberg, Ronald G. Labor Markets and Integrating National Economies. Brookings Institution Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0815722571

- Hayek, F.A. Studies in Philosophy, Politics and Economics Simon and Schuster. New York, 1969. ISBN 978-0671202460

- Kibbe, Matthew B. The Minimum Wage: Washington's Perennial Myth. Cato Policy Analysis No. 106, 1988.

- Manning, Alan. Monopsony in Motion: Imperfect Competition in Labor Markets. Princeton University Press, 2003.