Difference between revisions of "Matenadaran" - New World Encyclopedia

MaedaMartha (talk | contribs) (New page: {{wikify|date=April 2008}} {{coord|40|11|31.78|N|44|31|16.07|E|type:building|display=title}} thumb|The Matenadaran Institute building in [[Yerevan]] [[Image...) |

MaedaMartha (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | |||

{{wikify|date=April 2008}} | {{wikify|date=April 2008}} | ||

{{coord|40|11|31.78|N|44|31|16.07|E|type:building|display=title}} | {{coord|40|11|31.78|N|44|31|16.07|E|type:building|display=title}} | ||

| Line 6: | Line 7: | ||

[[Image:westdia ukazatel pointer 09 1.jpg|thumb|Pointer to the Matenadaran Institute building in Yerevan]] | [[Image:westdia ukazatel pointer 09 1.jpg|thumb|Pointer to the Matenadaran Institute building in Yerevan]] | ||

| − | The '''Matenadaran''' or '''Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts''' in [[Yerevan, Armenia]], is one of the richest depositories of [[manuscript]]s and [[book]]s in the world. | + | The '''Matenadaran''' or '''Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts''' in [[Yerevan, Armenia]], is one of the richest depositories of [[manuscript]]s and [[book]]s in the world. |

| + | The collection dates back to [[405]], when [[Saint Mesrop Mashtots]] created the [[Armenian alphabet]] and sent his disciples to [[Edessa, Mesopotamia|Edessa]], Constantinople, [[Athens]], [[Antioch]], [[Alexandria]], and other centers of learning to study the Greek language and bring back the masterpieces of Greek literature. After 1441, when the Residence of Armenian Supreme Patriarch-Catholicos was moved to Echmiadzin, hundreds of manuscripts were copied there and in nearby monasteries, especially during the 17th century. During the 18th century, tens of thousands of Armenian manuscripts perished or were carried away during repeated invasions, wars and plundering raids. In the late 19th century the collection expanded as private scholars procured and preserved manuscripts that had been scattered all over Europe. In [[1920]] the collection, held at the headquarters of the [[Armenian Apostolic Church]] at [[Echmiatsin]] was confiscated by the [[Bolsheviks]], combined with other collections and, in [[1939]], moved to [[Yerevan]]. On [[March 3]], [[1959]], the Matenadaran Institute was formed to maintain and house the manuscripts, and in [[1962]] it was named after Saint Mesrop Mashtots. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The collection now numbers over 100,000 manuscripts, documents and fragments containing texts on history, geography, philosophy, science, mathematics, astronomy, chemistry, medicine, church history and law. They are invaluable as historical sources. In some cases, original texts that were lost are preserved in Armenian translation, including Hermes Trismegistus' Interpretations, four chapters of Progymnasmata by Theon of Alexandria, and the second part of [[Eusebius]]'s ''Chronicle,'' of which only a few fragments exist in the Greek. Some originals of foreign mathematicians' works are also preserved at the Matenadaran, such as the Arabic manuscript of the Kitab al - Najat (The Book of Salvation), written by Avicenna (Abu Ali ibn - Sina). The Mashtots Matenadaran makes manuscripts available for study to historians, philologists and scholars. Since 1959, scholars of manuscripts in the Matenadaran have published more than 200 books. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==History== | ||

| + | ===Armenian alphabet=== | ||

| + | Matenadaran means ‘‘manuscript store’’ or ‘‘library’’ in ancient Armenian. The collection dates back to [[405]], when [[Saint Mesrop Mashtots]] created the [[Armenian alphabet]]. Saint Mesrop Mashtots (361 – 440), a dedicated evangelist, encountered difficulty instructing his converts because the Greek, Persian, and Syriac scripts then in use were not well-suited for representing the many complex sounds of their native tongue. With the support of [Isaac of Armenia|Patriarch Isaac]] and King [[Vramshapuh]], he created a written Armenian alphabet and began to propagate it by establishing schools. Anxious to provide a religious literature for sent them to [[Edessa, Mesopotamia|Edessa]], Constantinople, [[Athens]], [[Antioch]], [[Alexandria]], and other centers of learning to study the Greek language and bring back the masterpieces of Greek literature. | ||

| − | The | + | The first monument of this Armenian literature was the version of the Holy Scriptures translated from the Syriac text by Moses of Chorene around 411. Soon afterwards John of Egheghiatz and Joseph of Baghin were sent to Edessa to translate the Scriptures. They journeyed as far as Constantinople, and brought back with them authentic copies of the Greek text. With the help of other copies obtained from Alexandria the Bible was translated again from the Greek according to the text of the [[Septuagint]] and [[Origen]]'s ''[[Hexapla]]''. This version, now in use in the Armenian Church, was completed about 434. The decrees of the first three councils — [[First Council of Nicaea|Nicæa]], [[First Council of Constantinople|Constantinople]], and [[Council of Ephesus|Ephesus]] — and the national liturgy (so far written in Syriac) were also translated into Armenian. Many works of the Greek Fathers also passed into Armenian. |

| − | + | In ancient times and during the Middle Ages, manuscripts were reverentially guarded in Armenia and played an important role in the people’s fight against spiritual subjugation and assimilation. Major monasteries and universities had special writing rooms, where scribes sat for decades and copied by hand books by Armenian scholars and writers, and Armenian translations of works by foreign authors. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | === Echmiadzin Matenadaran=== | |

| + | According to the 5th century historian Ghazar Parpetsi the Echmiadzin Matenadaran existed as early as the 5th century. After 1441, when the Residence of Armenian Supreme Patriarch-Catholicos removed from Sis (Cilicia) to Echmiadzin, it became increasingly important. Hundreds of manuscripts were copied in Echmiadzin and nearby monasteries, especially during the 17th century, and the Echmiadzin Matenadaran became one of the richest manuscript depositories in the country. In a colophon of 1668 it is noted that in the times of Philipos Supreme Patriarch (1633-1655) the library of the Echmiadzin monastery was enriched with numerous manuscripts. Many manuscripts were procured during the rule of Hakob Jughayetsi (1655-1680). <ref> Matenadaran.am [http://www.matenadaran.am/en/history/index.html The History of Matenadaran] Retrieved November 14, 2008.</ref> | ||

| − | + | During the 18th century Echmiadzin was subjected to repeated invasions, wars and plundering raids. Tens of thousands of Armenian manuscripts perished. Approximately 25,000 have survived, including over 10,000 folios and also 2,500 fragments collected in the Matenadaran. The rest of them are the property of various museums and libraries throughout the world, chiefly in [[Venice]], [[Jerusalem]], [[Vienna]], [[Beirut]], [[Paris]], the Getty Museum in [[Los Angeles]] and [[London]]. Many manuscripts, like wounded soldiers, bear the marks of sword, blood and fire. <ref>Armeniapedia.org [http://www.armeniapedia.org/index.php?title=Matenadaran Matenadaran] Retrieved Novembr 15, 2008.</ref> | |

| − | + | At the beginning of the 19th century only a small number of the manuscripts from the rich collection of the Echmiadzin Matenadaran remained. The first catalogue of manuscripts of the Echmiadzin Matenadaran, compiled by Hovhannes archbishop Shahkhatunian and published in French and Russian translations in St. Petersburg in 1840, included 312 manuscripts. A second and larger catalogue, known as the 'Karenian catalogue,' including 2340 manuscripts, was compiled by Daniel bishop Shahnazarian and published in 1863. | |

| − | === | + | ===Expansion of the collection=== |

| − | |||

| − | + | The number of the Matenadaran manuscripts was increased when private specialists were involved in procuring, description and preservation of the manuscripts. In 1892 the Matenadaran had 3,158 manuscripts, in 1897 – 3,338, in 1906 – 3,788 and on the eve of the World War 1st (1913) – 4,060 manuscripts. In 1915 the Matenadaran received 1,628 manuscripts from Vaspurakan (Lim, Ktuts, Akhtamar, Varag, Van) and Tavriz<ref>Ibid.</ref> and the entire collection was taken to Moscow for safekeeping. | |

| − | The | + | The 4,060 manuscripts which had been taken to Moscow in 1915 for safekeeping were returned to Armenia in April, 1922. Another 1,730 manuscripts, collected from 1915 to 1921, were added to this collection. On December 17, 1929, the Echmiadzin Matenadaran was decreed state property. Soon the Matenadaran received collections from the Moscow Lazarian Institute of Oriental Languages, the Tiflis Nersessian Seminary, Armenian Ethnographic Society, and the Yerevan Literary Museum. |

| + | In 1939 the Echmiadzin Matenadaran was transferred to Yerevan. On March 3, 1959, by order of the Armenian Government, the Matenadaran was reorganized into specialized departments for scientific preservation, study, translation and publication of the manuscripts. Restoration and book-binding departments were established, and the manuscripts and archive documents were systematically described and catalogued. | ||

| − | + | === Matenadaran today=== | |

| − | + | Today the Matenadaran offers a number of catalogues, guide-books of manuscript notations and card indexes. The first and second volumes of the catalogue of the Armenian manuscripts were published in 1965 and 1970, containing detailed auxiliary lists of chronology, fragments, geographical names and forenames. In 1984 the first volume of the Main Catalogue was published. The Matenadaran has published a number of old Armenian literary classics including the works of ancient Armenian historians; a 'History of Georgia;' Armenian translations of the Greek philosophers Theon of Alexandria (1st century), Zeno, and Hermes Trismegistus (3rd century); works of Armenian philosophers and medieval poets; and volumes of Persian Firmans. <ref>Ibid.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | The | + | The Mashtots Matenadaran makes manuscripts available to historians, philologists and scholars. Since 1959, scholars of manuscripts in the Matenadaran have published more than 200 books. A scientific periodical 'Banber Matenadarani' ('Herald of the Matenadaran'), is regularly produced. |

| − | The | + | The Matenadaran is constantly acquiring manuscripts found in other countries. The excellent facilities for preservation and display of precious manuscripts at the Mashtots Matenadaran, together with its worldwide reputation, have inspired individuals both in Armenia and abroad to donate preserved manuscripts and fragments to the Matenadaran. Several hundred books dating from the thirteenth to eighteenth centuries have recently been sent by Armenians living in Libya, Syria, France, Bulgaria, Romania, India and the U.S.. In addition, a project is underway to register and catalogue Armenian manuscripts kept by individuals and to acquire microfilms of Armenian manuscripts kept in foreign museums and libraries in order to support scientific research and complete the collection, which now numbers over 100,000 manuscripts, documents and fragments. <ref>Armeniapedia.org [http://www.armeniapedia.org/index.php?title=Matenadaran Matenadaran] Retrieved Novembr 15, 2008.</ref> |

| − | + | ==The Museum== | |

| + | The Institute of Ancient Manuscripts (the Matenadaran), built in 1957, was designed by Mark Grigoryan. A flight of steps leads up to a statue of [[Mesrop Mashtots]], with the letters of the Armenian alphabet been carved into the wall behind. Before the entrance to the museum stand sculptures of six ancient Armenian philosophers, scientists and men of the arts. Beyond massive doors of embossed copper is an entrance hail decorated with a mosaic of the Avarair Battle which took place on May 26, 451, when the Armenian people rose against their conquerors. On the wall opposite the staircase a fresco by Ovanes Khachatryan depicts three different periods in the history and culture of the Armenian people. | ||

| − | The | + | Manuscript books and their wonderful illustrations are on display in the exhibition hall on the first floor. The most ancient parchment book in the museum is the Gospel of Lazarus, written in 887. There are fragments of earlier manuscripts from the fifth to eighth centuries. The most ancient paper manuscript dates from 981. On a separate stand is the largest Armenian manuscript in the world, weighing 34 kilograms and compiled using 700 calf skins. Next to it is a tiny book measuring 3 x 4 centimeters and weighing only 19 grams. Other interesting exhibits include the Gospels of 1053, 1193 and 1411 illustrated in unfading colors, translations from Aristotle, a unique ancient Assyrian manuscript and an ancient Indian manuscript on palm leaves in the shape of a fan. |

| + | Other relics in the exhibition include the first Armenian printed book “Parzatumar” (Explanatory Calendar), published in 1512 in Venice, and the first Armenian magazine “Azdardr” (The Messenger), first published in 1794 in the Indian city of Madras. Next to them are a Decree on the founding of Novo-Nakhichevan (a settlement near [[Rostov-on-Don]], now included within the city boundaries), signed by the Russian Empress Catherine II, and Napoleon Bonaparte’s signature. In 1978 the writer Marietta Shaginyan presented the Matenadaran with a previously unknown document bearing the signature of Goethe. | ||

| − | + | ==Matenadaran collection== | |

| − | + | === History=== | |

| − | + | The works of the Armenian historians are primary sources about the history of Armenia and its surrounding countries. The first work of the Armenian historiography, The life of Mashtots was written in the 440s and is preserved in a 13th-14th century copy. The History of Agathangelos (5th century) describes the struggle against paganism in Armenia, and the acknowledgement of Christianity as a state religion in 301. The History of Pavstos Buzand, a contemporary of Agathangelos, reflects the social and political life of Armenia from 330-387 and contains important information about the relationship between Armenia and Rome, and Armenia and Persia, well as the history of the peoples of Transcaucasia. The History of Armeniaо by Movses Khorenatsi is the first chronological history of the Armenian people from mythological times up to the 5th century C.E.. in chronological order. Several fragments and 31 manuscripts of his history, the oldest of which date from the 9th century, are preserved at the Matenadaran. Khorenatsi quoted the works of Greek and Syrian authors, some of who are known today only through these manuscripts. Khorenatsi’s source materials for the 'History of Armenia' include Armenian folk tales and the legends and songs of other peoples, lapidary inscriptions, and official documents. It contains the earliest reference to the Iranian folk hero Rostam. This work has been studied by scholars for over 200 years and translated into numerous languages, beginning with a summary by the Swedish scholar Henrich Brenner (1669 - 1732). In 1736 a Latin translation together with its Armenian original was published in London. | |

| − | + | 'The History of Vardan and the war of the Armenians', by the 5th century historian Yeghisheh, describes the struggle of the Armenians against Sassanian Persia in 451 C.E. and includes valuable information on the Zoroastrian religion and the political life of Persia. Two copies of 'The History of Armenia' by [[Ghazar P'arpec'i]], another 5th century historian, are preserved at the Matenadaran. His work refers to the historical events of the period from 387 to 486 C.E.. and includes events that occurred in Persia, the Byzantine Empire, Georgia, [[Caucasian Albania|Albania]] and other countries. The history of the 8th century historian Ghevond is a reliable source of information about the Arabian invasions of Armenia and Asia Minor. 'History of [[Caucasian Albania|Albania]]', attributed to Movses Kaghankatvatsi is the only source in the world literature dealing especially with the history of [[Caucasian Albania|Albania]] and incorporates the work of authors from the 7th to 10th centuries. | |

| − | + | The 11th century historian Aristakes Lastivertsi tells about the Turkish and Byzantine invasions and the mass migration of the Armenians to foreign countries. He describes internal conflicts, including the dishonesty of merchants, fraud, bribery, self-interest, and dissensions between princes which created difficult conditions in the country. The 12th and 13th centuries, when the Armenian State of Cilicia was established and Armenia became a crossroad for trade, produced more than ten historians and chronologists. From the 14th to the 16th centuries there was only one well-known historian, Toma Metsopetsi (1376/9 - 1446), who recorded the history of the invasions of Thamerlane and his descendents to Armenia. Minor chroniclers of this period describe the political and social life of the time. | |

| − | + | The 17th - 18th centuries were rich in both minor and significant historiographical works. The 'History of Armenia' by the 17th century historian Arakel Davrizhetsi deals with the events of 1601 - 1662 in Armenia, Albania, Georgia, Turkey, Iran and in the Armenian communities of Istanbul, Ispahan, and Lvov. It documents the deportation of the Armenians to Persia by the Persian Shah Abbas. The manuscripts of other important historians, chroniclers, and travelers, include the works of Zachariah Sarkavag (1620), Eremiah Chelepi (1637 - 1695), Kostand Dzhughayetsi (17th century), Essai Hasan - Dzhalalian (1728), Hakob Shamakhetsi (1763), and the Supreme Patriarch Simeon Yerevantsi (1780). | |

| − | The | ||

| − | + | Of particular historiographical value are the Armenian translations of foreign authors, such as Josephus Flavius, Eusebius of Caesarea, Socrates Scholasticus, Michael the Syrian, Martin of Poland, George Francesca and others. | |

| − | The | + | ===Geography=== |

| − | + | Later Armenian authors wrote extant works about near and faraway countries, their populations, political and social lives. A number of works of the medieval Armenian geographers are preserved at the Matenadaran. The oldest of these is the Geography of the 7th century scholar Anania Shirakatsi, drawing on a number of geographical sources of the ancient world to provide general information about the earth, its surface, climatic belts, seas and so on. The three known continents - Europe, Asia, and Africa are introduced in addition to detailed descriptions of Armenia, Georgia, [[Caucasian Albania|Albania]], Iran, and Messopotamia. Another of Shirakatsi’s works, Itinerary, preserved as seven manuscripts, contains the original of A List of Cities of India and Persia, compiled in the 12th century. The author, having traveled to India, mentions the main roads and the distances between towns, and gives information about the social life of the country, the trade relations, and the life and the customs of the Indian people. | |

| − | + | The manuscripts also contain information about the Arctic. The 13th century author Hovhannes Yerzenkatsi describes the farthest 'uninhabited and coldest' part of the earth, where 'in autumn and in spring the day lasts for six months,' caused, according to Yerzenkatsi, by the passage of the sun from one hemisphere to the other. The many manuscripts of the 13th century geographer Vardan’s Geography contain facts about various countries and peoples. | |

| − | + | Armenian travelers wrote about visits to India, Ethiopia, Iran, Egypt, several European countries. Martiros Yerzenkatsi (15th-16th centuries) described his journey to Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Flanders, France, Spain. Having reached the coast of the Atlantic Ocean, he gave information about the European towns, the sizes of their populations, several architectural monuments, and customs and traditions. The 15th century author Hovhannes Akhtamartsi recorded his impressions of Ethiopia. Karapet Baghishetsi (1550) created a Geography in poetry. Eremiah Chelepi Keomurchian (1637 - 1695) wrote The History of Istanbul, Hovhannes Toutoungi (1703) wrote The History of Ethiopia, Shahmurad Baghishetsi (17th-18th centuries) wrote The Description of the Town of Versailles, and Khachatur Tokhatetsi wrote a poem in 280 lines about Venice. In his textbook of trade, Kostandin Dzhughayetsi described the goods that were on sale in the Indian, Persian, Turkish towns, their prices, the currency systems of different countries, and the units of measure used there. | |

| − | + | ===Grammar=== | |

| − | + | The first grammatical works, mainly translations intended for school usage, were written in Armenia in the 5th century. Since ancient times, Armenian grammatical thought was guided by the grammatical principles of Dionysius Thrax (170-90 BC). Armenian grammarians studied and interpreted his Art of Grammar for about 1,000 years. Armenian interpretators of this work were David, Movses Kertogh (5th-6th centuries), Stepanos Sunetsi (735), Grigor Magistros (990-1059), Hovhannes Yerzenkatsi (1293), etc. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The Amenian grammarians created a unique Armenian grammar by applying the principles of Dionysius to the Armenian language. David withdrew from Dionysius and worked out his own theory of etymology. Movses Kertogh gave important information on phonetics. Stepanos Sunetsi worked out principles for the exact articulation of separate sounds and syllables and made the first classification of vowels and diphthongs. Grigor Magistros Pahlavuni gave much attention to the linguistic study of the languages related to Armenian, rejecting the method of free etymology and working out principles of borrowing. | |

| − | + | Manuscript Number 7117 (its original dates back to the 10th-11th centuries), includes, along with the Greek, Syriac, Latin, Georgian, Coptic and Arabic alphabets, a copy of the Albanian alphabet, believed to have been created by Mesrop Mashtots. The manuscript contains prayers in Greek, Syriac, Georgian, Persian, Arabic, Kurdish, and Turkmen. | |

| − | The | ||

| − | + | In the Armenian State of Cilicia, a new branch of grammar, 'the art of writing' was developed. The first orthographic reform was carried out, with an interest towards the Armenian and Hellenic traditions. The Art of Writing by the grammarian Aristakes Grich (12th century) included scientific remarks concerning the spelling of difficult and doubtful words. He worked out orthographic principles that served as a basis for all later Armenian orthographics. The principles of Aristakes were supplemented by Gevorg Skevratsi (1301), the first to work out the principles of syllabication. A number of his works are preserved at the Matenadaran, including three grammars, concerning the principles of syllabication, pronunciation and orthography. | |

| − | + | From the 12th-13th centuries the usage of the spoken language in the literary works began. Vardan Areveltsi (1269) wrote two of his grammatical works in modern Armenian (ashkharabar), and his Parts of Speech was the first attempt to give the principles of the Armenian syntax. Hovhannes Yerzenkatsi, in A collection of definition of suggested that grammar eliminates the obstacles between the human thought and speech. | |

| − | The | + | The grammarians of the 14th-15th centuries included Essai Nchetsi, Hovhannes Tsortsoretsi, Hovhannes Kurnetsi, Grigor Tatevatsi, Hakob Ghrimetsi, and Arakel Siunetsi, who examined the biological basis of speech, classified sounds according to the places of their articulation, and studied the organs of speech. The 16th century The Grammar of Kipchak' of Lusik Sarkavag recorded the language of the kipchaks, a people of Turkish origin who inhabited the western regions of the Golden Horde. |

| − | + | The Matenadaran also contains a number of Arabic books and text-books on Arabic grammar; the majority of them are the text-books called Sarfemir. | |

| − | + | ===Philosophy=== | |

| + | Philosophical thought reached a high degree of development in ancient and medieval Armenia. The manuscripts of the Matenadaran include the works of more than 30 Armenian philosophers, such as Eznik Koghbatsi, Movses Kertogh (5th century), David Anhaght (5th-6thth century), Stepanos Sunetsi (8th century), Hovhannes Sarkavag (1045/50-1129), Hovhannes Yerzenkatsi, Vahram Rabuni (13th century), Hovhan Vorotnetsi (1315-1386), Grigor Tatevatsi (1346-1409), Arakel Sunetsi (1425), and Stepanos Lehatsi (1699). The Refutation of the Sects of the 5th century by the Armenian philosopher Eznik Koghbatsi is the first original philosophical work written in Armenian after the creation of the Alphabet. The Definition of Philosophy by David Anhaght (5th-6th centuries) continued ancient Greek philosophical traditions, drawing on the theories of Platon, Aristotle, Pythagoras. | ||

| − | + | Medieval Armenian philosophers were interested in the primacy of sensually perceptible things and the role of the senses; the contradictions of natural phenomena; space and time; the origin and destruction of matter; and cognition. The 12th century scholar Hovhannes Sarkavag noted the role of experiment in the cognition of the world and advised testing knowledge by conducting experiments. Hovhannes Yerzenkatsi (13th century) regarded destruction as only an alteration of matter and wrote, “everything under the sun is movable and changeable. Elements originate regularly and are destroyed regularly. Changes depend 'on time and matter'.” | |

| − | + | Prominent late medieval philosopher and founder of the Tatev University, Hovhan Vorotnetsi, wrote The Interpretation of the Categories of Aristotle. | |

| − | + | Beginning from the 5th century, Armenian philosophers, along with writing original work, translated the works of foreign philosophers. There are many manuscripts at the Matenadaran containing the works of Aristotle (389-322 B.C.E.), Zeno, Theon of Alexandria (1st century AD), Secudius (2nd century AD), Porphyrius (232 - 303), Proclus Diadochus (412-485), and Olympiodorus the Junior (6th century), as well as the works of the medieval authors Joannes Damascenus (8th century), Gilbert de La Porree (transl. of the 14th century), Peter of Aragon (14thth century), and Clemente Galano. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Of exceptional value for the world science are those translations, originals of which have been lost and they are known only through their Armenian translations. Among them are Zenoнs On Nature, Timothy Qelurus' Objections, Hermes Trismegistus' Interpretations, and four chapters of Progymnasmata by Theon of Alexandria. The loss of the Greek originals has given some of these versions a special importance; the second part of [[Eusebius]]'s ''Chronicle,'' of which only a few fragments exist in the Greek, has been entirely preserved in Armenian. | |

| − | + | ===Law=== | |

| + | The Armenian bibliography is rich in manuscripts on church and secular law that regulated the church and political life of medieval Armenia. A number of these works were translated from other languages, adapted to conditions in Armenia and incorporated in works on law written in Armenian. | ||

| − | + | One of the oldest monuments of the Armenian church law is the Book of Canons by Hovhannes Odznetsi (728), containing the canons of the ecumenical councils, the ecclestical councils and the councils of the Armenian church. These canons regulate social relations within the church and out of it between individuals and ecclesiastic organizations. They concern marriage and morality, robbery and bribery, human vice and drunkenness, and other social problems. Unique editions of the Book of Canons were issued in the 11th century, as well as in the 13th century by Gevorg Yerzenkatsi and in the 17th century by Azaria Sasnetsi. There are also particular groups of manuscripts of special importance for studying the Book of Canons. | |

| − | + | The first attempt at compiling a book of civic law based on the Book of Canons was the Canonic Legislation of David Alavkavordi Gandzaketsi (1st half of the 12th century). Of particular importance to study of the Armenian canonical and civic law are The Universal Paper (1165) of Nerses Shnorhali and Exhortation for the Christians (13th century) of Hovhannes Yerzenkatsi. In the beginning of the 13th century, in Northern Armenia , under the patronage of the Zakarian dynasty, the first collection of the Armenian civic law, The Armenian Code of Law of Mekhitar Gosh, was compiled. Sembat Sparapet , the 13th century military commander of the Armenian State of Cilicia, compiled his Code of Law under the direct influence of this work. | |

| − | + | During the same period, under the supervision of Tarson's archbishop Nerses Lambronatsi, several monuments of Roman and Byzantine civic law were translated into Armenian from Greek, Syriac and Latin: a variety of Eckloga, the Syriac-Roman Codes of Law, the Military Constitution, and the Canons of the Benedictine religious order. In the 1260s Sembat Sparapet continued this enrichment of Armenian bibliography by translating from old French the Antioch assizes, one of the monuments of the civic law of the Crusades of the east. The French original of this work is lost. | |

| − | + | After the fall of the last Armenian kingdom (1375) many Armenian communities were founded outside of Armenia. The Armenian Codes of Law were translated into the languages of the countries in which they lived: Georgia, Crimea, Ukraine, Poland, and Russia. During the 14th and15th centuries in the Crimea, several classics of Armenian law were translated into Kiptchak, a Tatar language. In 1518 a collection of Armenian law, based on The Code of Law of Gosh, was translated into Latin in Poland by order of Polish king Sigizmund I. Another collection of Armenian law was incorporated into the Code of Law of the Georgian prince Vakhtang, and consequently into Tsarist Russia's Collection of Law in the 19th century. | |

| − | + | Under the influence of bourgeois revolutions, Shahamir Shahamirian, an Armenian public figure living in India, wrote Trap for the Fame, a unique state constitution envisaging the restoration of the Armenian state in Armenia after liberation from the Turks and Persians. Traditional Armenian law was merged with elements of the new bourgeois ideology. The constitution addresses the organization of the state, civil and criminal law, and questions of liberty and equal rights. The Matenadaran collection also contains copies of the programs for Armenian autonomy, discussed in Turkey after the Crimean war (1856). | |

| − | The | ||

| − | + | ===Medicine=== | |

| + | Armenian medical institutions and physicians are mentioned in the Armenian and foreign sources beginning with the 5th century. Medicine flourished in Armenia from the 11th to the 15th centuries, Physicians such as Mekhitar Heratsi (12th century) , Abusaid (12th century), Grigoris (12th-13th centuries), Faradj (13th century), and Amirdovlat Amassiatsi (15th century) made use of the achievements of Greek and Arab medicine and their own experience to create medical texts which were copied and used in practical medicine for centuries afterwards. | ||

| − | + | Autopsy was permitted in Armenia for educational purposes beginning in the 12th century; in the rest of Europe it was not permitted until the 16th century. Medical instruments preserved in many regions of Armenia testify to surgical operations. In the 12th to 14th centuries, Caesarian sections, ablation of internal tumors, and operative treatment of various female diseases were practiced in Armenia. Dipsacus was used for general and local anaesthesia during surgey. Zedoar, melilotus officinalis and other narcotic drugs were used as anaesthesia during childbirth. Silk threads were used to sew up the wounds after surgery. | |

| − | + | In Consolation of Fevers, Mekhitar Heratsi (12th century ) introduces the theory of mold as a cause of infections and allergic diseases, and suggested that diseases could penetrate into the body from the outer world. Heratsi wrote works about anatomy, biology, general pathology, pharmacology, ophthalmology and curative properties of stones. | |

| − | + | Manuscript number 415, written by Grigoris and copied in 1465-1473, consists of a pharmacology and a general medical study. He dealt with pathologic physiology, anatomy, prophylaxis and hospital treatment, and identified the nervous system and the brain as the ruling organs of the body. Amirdovlat Amassiatsi (1496) knew Greek, Arabic, Persian, Turkish and Latin, and studied Greek, Roman, Persian and Arabic medicine. In The usefulness of Medicine he presents the structure of a human being and more than two hundred different diseases, mentioning the means of their treatment. In Useless for Ignorants he summarized the experience of the medieval Armenian and foreign physicians, especially in the field of pharmacology. Akhrapatin, written by Amirdovlat in 1459, is a pharmacopoeia based on a work of the famous Jewish philosopher, theologian and physician Maimonides (Moisseus Ben Maimon, 1135-1204), which has not been preserved. To the 1,100 prescriptions given by Maimon, he added another 2,600, making a total of 3,700 prescriptions. | |

| − | + | Well-known successors of Amirdovlat were Asar Sebastatsi (17th century), who wrote Of the art of Medicine; and Poghos (also a physician of the 17th century). | |

| − | The | + | ===Mathematics=== |

| + | The Matenadaran has a section dedicated to scientific and mathematical documents which contains ancient copies of [[Euclid]]'s ''[[Euclid's Elements|Elements]].'' Arithmetics by Anania Shirakatsi, a 7th century scholar, is the oldest preserved complete manuscript on arithmetics and contains tables of the four arithmetical operations. Other works of Shirakatsi, such as Cosmography, On the signs of the Zodiac, On the clouds and atmospheric signs, On the movemenr of the Sun, On the meteorological phenomena, and On the Milky Way, are also preserved. In the Matenadaran. Shirakatsi mentioned the principles of chronology of the Egyptians, Jews, Assyrians, Greeks, Romans and Ethiopians, and spoke of the planetary motion and periodicity of lunar and solar eclipses. Accepting the roundness of the Earth, Shirakatsi expressed the opinion that the Sun illuminated both spheres of the Earth at different times and when it is night on one half, it is day on the other. He considered the Milky Way 'a mass of densely distributed and faintly luminous stars,' and believed that 'the moon has no natural light and reflects the light of the Sun'. He explains the solar eclipse as the result of the Moon's position between the Sun and the Earth. Shirakatsi gave interesting explanations for the causes of rain, snow, hail, thunder, wind, earthquake and other natural phenomena, and wrote works on the calendar, measurement, geography, history. His book 'Weights and measures' gave the Armenian system of weights and measures together with the corresponding Greek, Jewish, Assyrian and Persian systems. | ||

| − | + | Polygonal Numbers, a mathematical work of the 11th century author Hovhannes Sarkavag shows that the theory of numbers was taught at the Armenian schools. Its oldest copy is preserved at the Matenadaran (manuscript number 4150). Hovhannes Sarkavag also introduced the reform of the Armenian calendar. The problems of cosmography and calendar were also discussed by the 12th century author Nerses Shnorhali in About the Sky and its decoration, by the 13th century author Hovhannes Yerzenkatsi Pluz in About the heavenly movement, by the 14th century scholar Hakob Ghrimetsi, by Mekhitar in Khrakhtshanakanner, and by the 15th century scholar Sargis the Philosopher. | |

| − | Some originals of foreign mathematicians' works are also preserved at the Matenadaran. Among the Arabic manuscripts, for example, is the Kitab al - Najat (The Book of Salvation), written by | + | Armenian mathematicians translated the best mathematical works of other countries. In the manuscript number 4166, copied in the 12th century, several chapters of Euclid’s The Elements of Geometry (3rd century B.C.E.) have been preserved in the Armenian translation. Some originals of foreign mathematicians' works are also preserved at the Matenadaran. Among the Arabic manuscripts, for example, is the Kitab al - Najat (The Book of Salvation), written by Avicenna (Abu Ali ibn - Sina). |

| − | |||

===Alchemy=== | ===Alchemy=== | ||

| − | + | Among the Matenadaran manuscripts are important texts on chemistry and alchemy, including About Substance and Type by Hovhannes Yerzenkatsi (1283), the anonymous Methods of Smelting Gold (16th century), a herbal pharmacopoeia in which the diagrams of plants are accompanied with their Persian names, in order to eliminate confusion during preparation. Hovhannes Yerzenkatsi gave interesting information about salts, mines, acids, and new substances that appear during the combinations and separations of gases. | |

| − | + | The manuscripts of the Matenadaran themselves, with their beautiful fresh colors of paint and ink, the durable leather of their bindings, and the parchment, worked out in several stages bear witness to their makers’ knowledge of chemistry and techniques of preparation. Scribes and painters sometimes wrote about the methods and prescriptions for formulating paints and ink colors of high quality. | |

| − | |||

| − | The manuscripts of the Matenadaran, with | ||

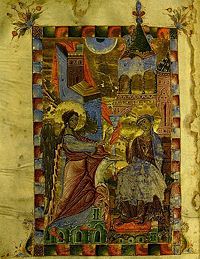

===Illuminated manuscripts=== | ===Illuminated manuscripts=== | ||

| Line 140: | Line 144: | ||

**Matenadaran Illuminated Ms. Gospel of Luke | **Matenadaran Illuminated Ms. Gospel of Luke | ||

**Chashots [[1286]]. Matenadaran Ms no. 979 | **Chashots [[1286]]. Matenadaran Ms no. 979 | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Notes== | ||

| + | {{reflist}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | * Abgarian, G. V. The Matenadaran. Erevan: Armenian State Pub. House. 1962. | ||

| + | * Chʻugaszyan, B. L., and S. S. Arevshati︠a︡. The Mashtots Matenadaran: a guidebook. Yerevan Armenian SSR: s.n.]. n. 1980 | ||

| + | * Durnovo, Lidii︠a︡ Aleksandrovna. Armenian miniatures. New York: H.N. Abrams. | ||

| + | * Klein, Jared S. 1996. On personal deixis in classical Armenian: a study of the syntax and semantics of the n-, s-, and d- demonstratives in manuscripts E and M of the Old Armenian Gospels. Dettelbach: Röll. 1961. ISBN 3927522244 | ||

| + | * Sanjian, Avedis Krikor. Colophons of Armenian manuscripts, 1301-1480; a source for Middle Eastern history. Harvard Armenian texts and studies, 2. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1969. ISBN 9780674142855 | ||

| + | * Stone, Nira, and Michael E. Stone. The Armenians: art, culture and religion. Dublin: Chester Beatty Library. 2007. ISBN 9781904832379 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| Line 150: | Line 165: | ||

[[Category:Manuscripts]] | [[Category:Manuscripts]] | ||

| − | + | Saint_Mesrob&oldid=246332099 | |

| − | |||

Revision as of 23:07, 15 November 2008

Coordinates:

The Matenadaran or Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts in Yerevan, Armenia, is one of the richest depositories of manuscripts and books in the world. The collection dates back to 405, when Saint Mesrop Mashtots created the Armenian alphabet and sent his disciples to Edessa, Constantinople, Athens, Antioch, Alexandria, and other centers of learning to study the Greek language and bring back the masterpieces of Greek literature. After 1441, when the Residence of Armenian Supreme Patriarch-Catholicos was moved to Echmiadzin, hundreds of manuscripts were copied there and in nearby monasteries, especially during the 17th century. During the 18th century, tens of thousands of Armenian manuscripts perished or were carried away during repeated invasions, wars and plundering raids. In the late 19th century the collection expanded as private scholars procured and preserved manuscripts that had been scattered all over Europe. In 1920 the collection, held at the headquarters of the Armenian Apostolic Church at Echmiatsin was confiscated by the Bolsheviks, combined with other collections and, in 1939, moved to Yerevan. On March 3, 1959, the Matenadaran Institute was formed to maintain and house the manuscripts, and in 1962 it was named after Saint Mesrop Mashtots.

The collection now numbers over 100,000 manuscripts, documents and fragments containing texts on history, geography, philosophy, science, mathematics, astronomy, chemistry, medicine, church history and law. They are invaluable as historical sources. In some cases, original texts that were lost are preserved in Armenian translation, including Hermes Trismegistus' Interpretations, four chapters of Progymnasmata by Theon of Alexandria, and the second part of Eusebius's Chronicle, of which only a few fragments exist in the Greek. Some originals of foreign mathematicians' works are also preserved at the Matenadaran, such as the Arabic manuscript of the Kitab al - Najat (The Book of Salvation), written by Avicenna (Abu Ali ibn - Sina). The Mashtots Matenadaran makes manuscripts available for study to historians, philologists and scholars. Since 1959, scholars of manuscripts in the Matenadaran have published more than 200 books.

History

Armenian alphabet

Matenadaran means ‘‘manuscript store’’ or ‘‘library’’ in ancient Armenian. The collection dates back to 405, when Saint Mesrop Mashtots created the Armenian alphabet. Saint Mesrop Mashtots (361 – 440), a dedicated evangelist, encountered difficulty instructing his converts because the Greek, Persian, and Syriac scripts then in use were not well-suited for representing the many complex sounds of their native tongue. With the support of [Isaac of Armenia|Patriarch Isaac]] and King Vramshapuh, he created a written Armenian alphabet and began to propagate it by establishing schools. Anxious to provide a religious literature for sent them to Edessa, Constantinople, Athens, Antioch, Alexandria, and other centers of learning to study the Greek language and bring back the masterpieces of Greek literature.

The first monument of this Armenian literature was the version of the Holy Scriptures translated from the Syriac text by Moses of Chorene around 411. Soon afterwards John of Egheghiatz and Joseph of Baghin were sent to Edessa to translate the Scriptures. They journeyed as far as Constantinople, and brought back with them authentic copies of the Greek text. With the help of other copies obtained from Alexandria the Bible was translated again from the Greek according to the text of the Septuagint and Origen's Hexapla. This version, now in use in the Armenian Church, was completed about 434. The decrees of the first three councils — Nicæa, Constantinople, and Ephesus — and the national liturgy (so far written in Syriac) were also translated into Armenian. Many works of the Greek Fathers also passed into Armenian.

In ancient times and during the Middle Ages, manuscripts were reverentially guarded in Armenia and played an important role in the people’s fight against spiritual subjugation and assimilation. Major monasteries and universities had special writing rooms, where scribes sat for decades and copied by hand books by Armenian scholars and writers, and Armenian translations of works by foreign authors.

Echmiadzin Matenadaran

According to the 5th century historian Ghazar Parpetsi the Echmiadzin Matenadaran existed as early as the 5th century. After 1441, when the Residence of Armenian Supreme Patriarch-Catholicos removed from Sis (Cilicia) to Echmiadzin, it became increasingly important. Hundreds of manuscripts were copied in Echmiadzin and nearby monasteries, especially during the 17th century, and the Echmiadzin Matenadaran became one of the richest manuscript depositories in the country. In a colophon of 1668 it is noted that in the times of Philipos Supreme Patriarch (1633-1655) the library of the Echmiadzin monastery was enriched with numerous manuscripts. Many manuscripts were procured during the rule of Hakob Jughayetsi (1655-1680). [1]

During the 18th century Echmiadzin was subjected to repeated invasions, wars and plundering raids. Tens of thousands of Armenian manuscripts perished. Approximately 25,000 have survived, including over 10,000 folios and also 2,500 fragments collected in the Matenadaran. The rest of them are the property of various museums and libraries throughout the world, chiefly in Venice, Jerusalem, Vienna, Beirut, Paris, the Getty Museum in Los Angeles and London. Many manuscripts, like wounded soldiers, bear the marks of sword, blood and fire. [2]

At the beginning of the 19th century only a small number of the manuscripts from the rich collection of the Echmiadzin Matenadaran remained. The first catalogue of manuscripts of the Echmiadzin Matenadaran, compiled by Hovhannes archbishop Shahkhatunian and published in French and Russian translations in St. Petersburg in 1840, included 312 manuscripts. A second and larger catalogue, known as the 'Karenian catalogue,' including 2340 manuscripts, was compiled by Daniel bishop Shahnazarian and published in 1863.

Expansion of the collection

The number of the Matenadaran manuscripts was increased when private specialists were involved in procuring, description and preservation of the manuscripts. In 1892 the Matenadaran had 3,158 manuscripts, in 1897 – 3,338, in 1906 – 3,788 and on the eve of the World War 1st (1913) – 4,060 manuscripts. In 1915 the Matenadaran received 1,628 manuscripts from Vaspurakan (Lim, Ktuts, Akhtamar, Varag, Van) and Tavriz[3] and the entire collection was taken to Moscow for safekeeping.

The 4,060 manuscripts which had been taken to Moscow in 1915 for safekeeping were returned to Armenia in April, 1922. Another 1,730 manuscripts, collected from 1915 to 1921, were added to this collection. On December 17, 1929, the Echmiadzin Matenadaran was decreed state property. Soon the Matenadaran received collections from the Moscow Lazarian Institute of Oriental Languages, the Tiflis Nersessian Seminary, Armenian Ethnographic Society, and the Yerevan Literary Museum. In 1939 the Echmiadzin Matenadaran was transferred to Yerevan. On March 3, 1959, by order of the Armenian Government, the Matenadaran was reorganized into specialized departments for scientific preservation, study, translation and publication of the manuscripts. Restoration and book-binding departments were established, and the manuscripts and archive documents were systematically described and catalogued.

Matenadaran today

Today the Matenadaran offers a number of catalogues, guide-books of manuscript notations and card indexes. The first and second volumes of the catalogue of the Armenian manuscripts were published in 1965 and 1970, containing detailed auxiliary lists of chronology, fragments, geographical names and forenames. In 1984 the first volume of the Main Catalogue was published. The Matenadaran has published a number of old Armenian literary classics including the works of ancient Armenian historians; a 'History of Georgia;' Armenian translations of the Greek philosophers Theon of Alexandria (1st century), Zeno, and Hermes Trismegistus (3rd century); works of Armenian philosophers and medieval poets; and volumes of Persian Firmans. [4]

The Mashtots Matenadaran makes manuscripts available to historians, philologists and scholars. Since 1959, scholars of manuscripts in the Matenadaran have published more than 200 books. A scientific periodical 'Banber Matenadarani' ('Herald of the Matenadaran'), is regularly produced.

The Matenadaran is constantly acquiring manuscripts found in other countries. The excellent facilities for preservation and display of precious manuscripts at the Mashtots Matenadaran, together with its worldwide reputation, have inspired individuals both in Armenia and abroad to donate preserved manuscripts and fragments to the Matenadaran. Several hundred books dating from the thirteenth to eighteenth centuries have recently been sent by Armenians living in Libya, Syria, France, Bulgaria, Romania, India and the U.S.. In addition, a project is underway to register and catalogue Armenian manuscripts kept by individuals and to acquire microfilms of Armenian manuscripts kept in foreign museums and libraries in order to support scientific research and complete the collection, which now numbers over 100,000 manuscripts, documents and fragments. [5]

The Museum

The Institute of Ancient Manuscripts (the Matenadaran), built in 1957, was designed by Mark Grigoryan. A flight of steps leads up to a statue of Mesrop Mashtots, with the letters of the Armenian alphabet been carved into the wall behind. Before the entrance to the museum stand sculptures of six ancient Armenian philosophers, scientists and men of the arts. Beyond massive doors of embossed copper is an entrance hail decorated with a mosaic of the Avarair Battle which took place on May 26, 451, when the Armenian people rose against their conquerors. On the wall opposite the staircase a fresco by Ovanes Khachatryan depicts three different periods in the history and culture of the Armenian people.

Manuscript books and their wonderful illustrations are on display in the exhibition hall on the first floor. The most ancient parchment book in the museum is the Gospel of Lazarus, written in 887. There are fragments of earlier manuscripts from the fifth to eighth centuries. The most ancient paper manuscript dates from 981. On a separate stand is the largest Armenian manuscript in the world, weighing 34 kilograms and compiled using 700 calf skins. Next to it is a tiny book measuring 3 x 4 centimeters and weighing only 19 grams. Other interesting exhibits include the Gospels of 1053, 1193 and 1411 illustrated in unfading colors, translations from Aristotle, a unique ancient Assyrian manuscript and an ancient Indian manuscript on palm leaves in the shape of a fan. Other relics in the exhibition include the first Armenian printed book “Parzatumar” (Explanatory Calendar), published in 1512 in Venice, and the first Armenian magazine “Azdardr” (The Messenger), first published in 1794 in the Indian city of Madras. Next to them are a Decree on the founding of Novo-Nakhichevan (a settlement near Rostov-on-Don, now included within the city boundaries), signed by the Russian Empress Catherine II, and Napoleon Bonaparte’s signature. In 1978 the writer Marietta Shaginyan presented the Matenadaran with a previously unknown document bearing the signature of Goethe.

Matenadaran collection

History

The works of the Armenian historians are primary sources about the history of Armenia and its surrounding countries. The first work of the Armenian historiography, The life of Mashtots was written in the 440s and is preserved in a 13th-14th century copy. The History of Agathangelos (5th century) describes the struggle against paganism in Armenia, and the acknowledgement of Christianity as a state religion in 301. The History of Pavstos Buzand, a contemporary of Agathangelos, reflects the social and political life of Armenia from 330-387 and contains important information about the relationship between Armenia and Rome, and Armenia and Persia, well as the history of the peoples of Transcaucasia. The History of Armeniaо by Movses Khorenatsi is the first chronological history of the Armenian people from mythological times up to the 5th century C.E.. in chronological order. Several fragments and 31 manuscripts of his history, the oldest of which date from the 9th century, are preserved at the Matenadaran. Khorenatsi quoted the works of Greek and Syrian authors, some of who are known today only through these manuscripts. Khorenatsi’s source materials for the 'History of Armenia' include Armenian folk tales and the legends and songs of other peoples, lapidary inscriptions, and official documents. It contains the earliest reference to the Iranian folk hero Rostam. This work has been studied by scholars for over 200 years and translated into numerous languages, beginning with a summary by the Swedish scholar Henrich Brenner (1669 - 1732). In 1736 a Latin translation together with its Armenian original was published in London.

'The History of Vardan and the war of the Armenians', by the 5th century historian Yeghisheh, describes the struggle of the Armenians against Sassanian Persia in 451 C.E. and includes valuable information on the Zoroastrian religion and the political life of Persia. Two copies of 'The History of Armenia' by Ghazar P'arpec'i, another 5th century historian, are preserved at the Matenadaran. His work refers to the historical events of the period from 387 to 486 C.E. and includes events that occurred in Persia, the Byzantine Empire, Georgia, Albania and other countries. The history of the 8th century historian Ghevond is a reliable source of information about the Arabian invasions of Armenia and Asia Minor. 'History of Albania', attributed to Movses Kaghankatvatsi is the only source in the world literature dealing especially with the history of Albania and incorporates the work of authors from the 7th to 10th centuries.

The 11th century historian Aristakes Lastivertsi tells about the Turkish and Byzantine invasions and the mass migration of the Armenians to foreign countries. He describes internal conflicts, including the dishonesty of merchants, fraud, bribery, self-interest, and dissensions between princes which created difficult conditions in the country. The 12th and 13th centuries, when the Armenian State of Cilicia was established and Armenia became a crossroad for trade, produced more than ten historians and chronologists. From the 14th to the 16th centuries there was only one well-known historian, Toma Metsopetsi (1376/9 - 1446), who recorded the history of the invasions of Thamerlane and his descendents to Armenia. Minor chroniclers of this period describe the political and social life of the time.

The 17th - 18th centuries were rich in both minor and significant historiographical works. The 'History of Armenia' by the 17th century historian Arakel Davrizhetsi deals with the events of 1601 - 1662 in Armenia, Albania, Georgia, Turkey, Iran and in the Armenian communities of Istanbul, Ispahan, and Lvov. It documents the deportation of the Armenians to Persia by the Persian Shah Abbas. The manuscripts of other important historians, chroniclers, and travelers, include the works of Zachariah Sarkavag (1620), Eremiah Chelepi (1637 - 1695), Kostand Dzhughayetsi (17th century), Essai Hasan - Dzhalalian (1728), Hakob Shamakhetsi (1763), and the Supreme Patriarch Simeon Yerevantsi (1780).

Of particular historiographical value are the Armenian translations of foreign authors, such as Josephus Flavius, Eusebius of Caesarea, Socrates Scholasticus, Michael the Syrian, Martin of Poland, George Francesca and others.

Geography

Later Armenian authors wrote extant works about near and faraway countries, their populations, political and social lives. A number of works of the medieval Armenian geographers are preserved at the Matenadaran. The oldest of these is the Geography of the 7th century scholar Anania Shirakatsi, drawing on a number of geographical sources of the ancient world to provide general information about the earth, its surface, climatic belts, seas and so on. The three known continents - Europe, Asia, and Africa are introduced in addition to detailed descriptions of Armenia, Georgia, Albania, Iran, and Messopotamia. Another of Shirakatsi’s works, Itinerary, preserved as seven manuscripts, contains the original of A List of Cities of India and Persia, compiled in the 12th century. The author, having traveled to India, mentions the main roads and the distances between towns, and gives information about the social life of the country, the trade relations, and the life and the customs of the Indian people.

The manuscripts also contain information about the Arctic. The 13th century author Hovhannes Yerzenkatsi describes the farthest 'uninhabited and coldest' part of the earth, where 'in autumn and in spring the day lasts for six months,' caused, according to Yerzenkatsi, by the passage of the sun from one hemisphere to the other. The many manuscripts of the 13th century geographer Vardan’s Geography contain facts about various countries and peoples.

Armenian travelers wrote about visits to India, Ethiopia, Iran, Egypt, several European countries. Martiros Yerzenkatsi (15th-16th centuries) described his journey to Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Flanders, France, Spain. Having reached the coast of the Atlantic Ocean, he gave information about the European towns, the sizes of their populations, several architectural monuments, and customs and traditions. The 15th century author Hovhannes Akhtamartsi recorded his impressions of Ethiopia. Karapet Baghishetsi (1550) created a Geography in poetry. Eremiah Chelepi Keomurchian (1637 - 1695) wrote The History of Istanbul, Hovhannes Toutoungi (1703) wrote The History of Ethiopia, Shahmurad Baghishetsi (17th-18th centuries) wrote The Description of the Town of Versailles, and Khachatur Tokhatetsi wrote a poem in 280 lines about Venice. In his textbook of trade, Kostandin Dzhughayetsi described the goods that were on sale in the Indian, Persian, Turkish towns, their prices, the currency systems of different countries, and the units of measure used there.

Grammar

The first grammatical works, mainly translations intended for school usage, were written in Armenia in the 5th century. Since ancient times, Armenian grammatical thought was guided by the grammatical principles of Dionysius Thrax (170-90 B.C.E.). Armenian grammarians studied and interpreted his Art of Grammar for about 1,000 years. Armenian interpretators of this work were David, Movses Kertogh (5th-6th centuries), Stepanos Sunetsi (735), Grigor Magistros (990-1059), Hovhannes Yerzenkatsi (1293), etc.

The Amenian grammarians created a unique Armenian grammar by applying the principles of Dionysius to the Armenian language. David withdrew from Dionysius and worked out his own theory of etymology. Movses Kertogh gave important information on phonetics. Stepanos Sunetsi worked out principles for the exact articulation of separate sounds and syllables and made the first classification of vowels and diphthongs. Grigor Magistros Pahlavuni gave much attention to the linguistic study of the languages related to Armenian, rejecting the method of free etymology and working out principles of borrowing.

Manuscript Number 7117 (its original dates back to the 10th-11th centuries), includes, along with the Greek, Syriac, Latin, Georgian, Coptic and Arabic alphabets, a copy of the Albanian alphabet, believed to have been created by Mesrop Mashtots. The manuscript contains prayers in Greek, Syriac, Georgian, Persian, Arabic, Kurdish, and Turkmen.

In the Armenian State of Cilicia, a new branch of grammar, 'the art of writing' was developed. The first orthographic reform was carried out, with an interest towards the Armenian and Hellenic traditions. The Art of Writing by the grammarian Aristakes Grich (12th century) included scientific remarks concerning the spelling of difficult and doubtful words. He worked out orthographic principles that served as a basis for all later Armenian orthographics. The principles of Aristakes were supplemented by Gevorg Skevratsi (1301), the first to work out the principles of syllabication. A number of his works are preserved at the Matenadaran, including three grammars, concerning the principles of syllabication, pronunciation and orthography.

From the 12th-13th centuries the usage of the spoken language in the literary works began. Vardan Areveltsi (1269) wrote two of his grammatical works in modern Armenian (ashkharabar), and his Parts of Speech was the first attempt to give the principles of the Armenian syntax. Hovhannes Yerzenkatsi, in A collection of definition of suggested that grammar eliminates the obstacles between the human thought and speech.

The grammarians of the 14th-15th centuries included Essai Nchetsi, Hovhannes Tsortsoretsi, Hovhannes Kurnetsi, Grigor Tatevatsi, Hakob Ghrimetsi, and Arakel Siunetsi, who examined the biological basis of speech, classified sounds according to the places of their articulation, and studied the organs of speech. The 16th century The Grammar of Kipchak' of Lusik Sarkavag recorded the language of the kipchaks, a people of Turkish origin who inhabited the western regions of the Golden Horde.

The Matenadaran also contains a number of Arabic books and text-books on Arabic grammar; the majority of them are the text-books called Sarfemir.

Philosophy

Philosophical thought reached a high degree of development in ancient and medieval Armenia. The manuscripts of the Matenadaran include the works of more than 30 Armenian philosophers, such as Eznik Koghbatsi, Movses Kertogh (5th century), David Anhaght (5th-6thth century), Stepanos Sunetsi (8th century), Hovhannes Sarkavag (1045/50-1129), Hovhannes Yerzenkatsi, Vahram Rabuni (13th century), Hovhan Vorotnetsi (1315-1386), Grigor Tatevatsi (1346-1409), Arakel Sunetsi (1425), and Stepanos Lehatsi (1699). The Refutation of the Sects of the 5th century by the Armenian philosopher Eznik Koghbatsi is the first original philosophical work written in Armenian after the creation of the Alphabet. The Definition of Philosophy by David Anhaght (5th-6th centuries) continued ancient Greek philosophical traditions, drawing on the theories of Platon, Aristotle, Pythagoras.

Medieval Armenian philosophers were interested in the primacy of sensually perceptible things and the role of the senses; the contradictions of natural phenomena; space and time; the origin and destruction of matter; and cognition. The 12th century scholar Hovhannes Sarkavag noted the role of experiment in the cognition of the world and advised testing knowledge by conducting experiments. Hovhannes Yerzenkatsi (13th century) regarded destruction as only an alteration of matter and wrote, “everything under the sun is movable and changeable. Elements originate regularly and are destroyed regularly. Changes depend 'on time and matter'.”

Prominent late medieval philosopher and founder of the Tatev University, Hovhan Vorotnetsi, wrote The Interpretation of the Categories of Aristotle.

Beginning from the 5th century, Armenian philosophers, along with writing original work, translated the works of foreign philosophers. There are many manuscripts at the Matenadaran containing the works of Aristotle (389-322 B.C.E.), Zeno, Theon of Alexandria (1st century AD), Secudius (2nd century AD), Porphyrius (232 - 303), Proclus Diadochus (412-485), and Olympiodorus the Junior (6th century), as well as the works of the medieval authors Joannes Damascenus (8th century), Gilbert de La Porree (transl. of the 14th century), Peter of Aragon (14thth century), and Clemente Galano.

Of exceptional value for the world science are those translations, originals of which have been lost and they are known only through their Armenian translations. Among them are Zenoнs On Nature, Timothy Qelurus' Objections, Hermes Trismegistus' Interpretations, and four chapters of Progymnasmata by Theon of Alexandria. The loss of the Greek originals has given some of these versions a special importance; the second part of Eusebius's Chronicle, of which only a few fragments exist in the Greek, has been entirely preserved in Armenian.

Law

The Armenian bibliography is rich in manuscripts on church and secular law that regulated the church and political life of medieval Armenia. A number of these works were translated from other languages, adapted to conditions in Armenia and incorporated in works on law written in Armenian.

One of the oldest monuments of the Armenian church law is the Book of Canons by Hovhannes Odznetsi (728), containing the canons of the ecumenical councils, the ecclestical councils and the councils of the Armenian church. These canons regulate social relations within the church and out of it between individuals and ecclesiastic organizations. They concern marriage and morality, robbery and bribery, human vice and drunkenness, and other social problems. Unique editions of the Book of Canons were issued in the 11th century, as well as in the 13th century by Gevorg Yerzenkatsi and in the 17th century by Azaria Sasnetsi. There are also particular groups of manuscripts of special importance for studying the Book of Canons.

The first attempt at compiling a book of civic law based on the Book of Canons was the Canonic Legislation of David Alavkavordi Gandzaketsi (1st half of the 12th century). Of particular importance to study of the Armenian canonical and civic law are The Universal Paper (1165) of Nerses Shnorhali and Exhortation for the Christians (13th century) of Hovhannes Yerzenkatsi. In the beginning of the 13th century, in Northern Armenia , under the patronage of the Zakarian dynasty, the first collection of the Armenian civic law, The Armenian Code of Law of Mekhitar Gosh, was compiled. Sembat Sparapet , the 13th century military commander of the Armenian State of Cilicia, compiled his Code of Law under the direct influence of this work.

During the same period, under the supervision of Tarson's archbishop Nerses Lambronatsi, several monuments of Roman and Byzantine civic law were translated into Armenian from Greek, Syriac and Latin: a variety of Eckloga, the Syriac-Roman Codes of Law, the Military Constitution, and the Canons of the Benedictine religious order. In the 1260s Sembat Sparapet continued this enrichment of Armenian bibliography by translating from old French the Antioch assizes, one of the monuments of the civic law of the Crusades of the east. The French original of this work is lost.

After the fall of the last Armenian kingdom (1375) many Armenian communities were founded outside of Armenia. The Armenian Codes of Law were translated into the languages of the countries in which they lived: Georgia, Crimea, Ukraine, Poland, and Russia. During the 14th and15th centuries in the Crimea, several classics of Armenian law were translated into Kiptchak, a Tatar language. In 1518 a collection of Armenian law, based on The Code of Law of Gosh, was translated into Latin in Poland by order of Polish king Sigizmund I. Another collection of Armenian law was incorporated into the Code of Law of the Georgian prince Vakhtang, and consequently into Tsarist Russia's Collection of Law in the 19th century.

Under the influence of bourgeois revolutions, Shahamir Shahamirian, an Armenian public figure living in India, wrote Trap for the Fame, a unique state constitution envisaging the restoration of the Armenian state in Armenia after liberation from the Turks and Persians. Traditional Armenian law was merged with elements of the new bourgeois ideology. The constitution addresses the organization of the state, civil and criminal law, and questions of liberty and equal rights. The Matenadaran collection also contains copies of the programs for Armenian autonomy, discussed in Turkey after the Crimean war (1856).

Medicine

Armenian medical institutions and physicians are mentioned in the Armenian and foreign sources beginning with the 5th century. Medicine flourished in Armenia from the 11th to the 15th centuries, Physicians such as Mekhitar Heratsi (12th century) , Abusaid (12th century), Grigoris (12th-13th centuries), Faradj (13th century), and Amirdovlat Amassiatsi (15th century) made use of the achievements of Greek and Arab medicine and their own experience to create medical texts which were copied and used in practical medicine for centuries afterwards.

Autopsy was permitted in Armenia for educational purposes beginning in the 12th century; in the rest of Europe it was not permitted until the 16th century. Medical instruments preserved in many regions of Armenia testify to surgical operations. In the 12th to 14th centuries, Caesarian sections, ablation of internal tumors, and operative treatment of various female diseases were practiced in Armenia. Dipsacus was used for general and local anaesthesia during surgey. Zedoar, melilotus officinalis and other narcotic drugs were used as anaesthesia during childbirth. Silk threads were used to sew up the wounds after surgery.

In Consolation of Fevers, Mekhitar Heratsi (12th century ) introduces the theory of mold as a cause of infections and allergic diseases, and suggested that diseases could penetrate into the body from the outer world. Heratsi wrote works about anatomy, biology, general pathology, pharmacology, ophthalmology and curative properties of stones.

Manuscript number 415, written by Grigoris and copied in 1465-1473, consists of a pharmacology and a general medical study. He dealt with pathologic physiology, anatomy, prophylaxis and hospital treatment, and identified the nervous system and the brain as the ruling organs of the body. Amirdovlat Amassiatsi (1496) knew Greek, Arabic, Persian, Turkish and Latin, and studied Greek, Roman, Persian and Arabic medicine. In The usefulness of Medicine he presents the structure of a human being and more than two hundred different diseases, mentioning the means of their treatment. In Useless for Ignorants he summarized the experience of the medieval Armenian and foreign physicians, especially in the field of pharmacology. Akhrapatin, written by Amirdovlat in 1459, is a pharmacopoeia based on a work of the famous Jewish philosopher, theologian and physician Maimonides (Moisseus Ben Maimon, 1135-1204), which has not been preserved. To the 1,100 prescriptions given by Maimon, he added another 2,600, making a total of 3,700 prescriptions.

Well-known successors of Amirdovlat were Asar Sebastatsi (17th century), who wrote Of the art of Medicine; and Poghos (also a physician of the 17th century).

Mathematics

The Matenadaran has a section dedicated to scientific and mathematical documents which contains ancient copies of Euclid's Elements. Arithmetics by Anania Shirakatsi, a 7th century scholar, is the oldest preserved complete manuscript on arithmetics and contains tables of the four arithmetical operations. Other works of Shirakatsi, such as Cosmography, On the signs of the Zodiac, On the clouds and atmospheric signs, On the movemenr of the Sun, On the meteorological phenomena, and On the Milky Way, are also preserved. In the Matenadaran. Shirakatsi mentioned the principles of chronology of the Egyptians, Jews, Assyrians, Greeks, Romans and Ethiopians, and spoke of the planetary motion and periodicity of lunar and solar eclipses. Accepting the roundness of the Earth, Shirakatsi expressed the opinion that the Sun illuminated both spheres of the Earth at different times and when it is night on one half, it is day on the other. He considered the Milky Way 'a mass of densely distributed and faintly luminous stars,' and believed that 'the moon has no natural light and reflects the light of the Sun'. He explains the solar eclipse as the result of the Moon's position between the Sun and the Earth. Shirakatsi gave interesting explanations for the causes of rain, snow, hail, thunder, wind, earthquake and other natural phenomena, and wrote works on the calendar, measurement, geography, history. His book 'Weights and measures' gave the Armenian system of weights and measures together with the corresponding Greek, Jewish, Assyrian and Persian systems.

Polygonal Numbers, a mathematical work of the 11th century author Hovhannes Sarkavag shows that the theory of numbers was taught at the Armenian schools. Its oldest copy is preserved at the Matenadaran (manuscript number 4150). Hovhannes Sarkavag also introduced the reform of the Armenian calendar. The problems of cosmography and calendar were also discussed by the 12th century author Nerses Shnorhali in About the Sky and its decoration, by the 13th century author Hovhannes Yerzenkatsi Pluz in About the heavenly movement, by the 14th century scholar Hakob Ghrimetsi, by Mekhitar in Khrakhtshanakanner, and by the 15th century scholar Sargis the Philosopher.

Armenian mathematicians translated the best mathematical works of other countries. In the manuscript number 4166, copied in the 12th century, several chapters of Euclid’s The Elements of Geometry (3rd century B.C.E.) have been preserved in the Armenian translation. Some originals of foreign mathematicians' works are also preserved at the Matenadaran. Among the Arabic manuscripts, for example, is the Kitab al - Najat (The Book of Salvation), written by Avicenna (Abu Ali ibn - Sina).

Alchemy

Among the Matenadaran manuscripts are important texts on chemistry and alchemy, including About Substance and Type by Hovhannes Yerzenkatsi (1283), the anonymous Methods of Smelting Gold (16th century), a herbal pharmacopoeia in which the diagrams of plants are accompanied with their Persian names, in order to eliminate confusion during preparation. Hovhannes Yerzenkatsi gave interesting information about salts, mines, acids, and new substances that appear during the combinations and separations of gases.

The manuscripts of the Matenadaran themselves, with their beautiful fresh colors of paint and ink, the durable leather of their bindings, and the parchment, worked out in several stages bear witness to their makers’ knowledge of chemistry and techniques of preparation. Scribes and painters sometimes wrote about the methods and prescriptions for formulating paints and ink colors of high quality.

Illuminated manuscripts

- 2500 Armenian illuminated manuscripts

- Echmiadzin Gospel (989)

- Mugni Gospels (1060)

- Gospel of Malat'ya 1267–1268. Matenadaran Ms no. 10675

- Gospel of Princess K'eran 1265 By the Illumination Artist Toros Roslin.

- Gospel Matenadaran Ms no. 7648 XIIITH CEN

- Matenadaran Gospel [1287] no. 197.

- Matenadaran Illuminated Ms. Gospel of Luke

- Chashots 1286. Matenadaran Ms no. 979

Notes

- ↑ Matenadaran.am The History of Matenadaran Retrieved November 14, 2008.

- ↑ Armeniapedia.org Matenadaran Retrieved Novembr 15, 2008.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Armeniapedia.org Matenadaran Retrieved Novembr 15, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Abgarian, G. V. The Matenadaran. Erevan: Armenian State Pub. House. 1962.

- Chʻugaszyan, B. L., and S. S. Arevshati︠a︡. The Mashtots Matenadaran: a guidebook. Yerevan Armenian SSR: s.n.]. n. 1980

- Durnovo, Lidii︠a︡ Aleksandrovna. Armenian miniatures. New York: H.N. Abrams.

- Klein, Jared S. 1996. On personal deixis in classical Armenian: a study of the syntax and semantics of the n-, s-, and d- demonstratives in manuscripts E and M of the Old Armenian Gospels. Dettelbach: Röll. 1961. ISBN 3927522244

- Sanjian, Avedis Krikor. Colophons of Armenian manuscripts, 1301-1480; a source for Middle Eastern history. Harvard Armenian texts and studies, 2. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1969. ISBN 9780674142855

- Stone, Nira, and Michael E. Stone. The Armenians: art, culture and religion. Dublin: Chester Beatty Library. 2007. ISBN 9781904832379

External links

- Template:Commons-inline

- Official site

- Armeniapedia — Matenadaran

Saint_Mesrob&oldid=246332099