Difference between revisions of "Isidore of Seville" - New World Encyclopedia

(New page: {{dablink|See Isidore and Isidro for namesakes.}} ---- {| style="position:relative; margin: 0 0 0.5em 1em; border-collapse: collapse; float:right; background:white; clear:right; w...) |

Makoto Maeda (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|'''Born''' | |'''Born''' | ||

| − | |c. | + | |c.560 at Cartagena, Spain |

|- | |- | ||

|'''Died''' | |'''Died''' | ||

| − | | | + | |April 4, 636 at Seville, Spain |

|- | |- | ||

|'''Venerated in''' | |'''Venerated in''' | ||

| − | | | + | |Roman Catholic Church |

|- | |- | ||

| − | |''' | + | |'''Calendar of saints|Feast''' |

| − | | | + | |April 4 |

|- | |- | ||

|'''Attributes''' | |'''Attributes''' | ||

|bees; bishop holding a pen while surrounded by a swarm of bees; bishop standing near a beehive; old bishop with a prince at his feet; pen; priest or bishop with pen and book; with Saint Leander, Saint Fulgentius, and Saint Florentina; with his Etymologia | |bees; bishop holding a pen while surrounded by a swarm of bees; bishop standing near a beehive; old bishop with a prince at his feet; pen; priest or bishop with pen and book; with Saint Leander, Saint Fulgentius, and Saint Florentina; with his Etymologia | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |''' | + | |'''Patronage''' |

| − | | | + | |students |

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

{{portalpar|Saints}} | {{portalpar|Saints}} | ||

| − | '''Saint Isidore of Seville''' ([[Spanish language|Spanish]]: {{lang|es|'''San Isidro'''}} or {{lang|es|'''San Isidoro de Sevilla'''}}) (c. | + | '''Saint Isidore of Seville''' ([[Spanish language|Spanish]]: {{lang|es|'''San Isidro'''}} or {{lang|es|'''San Isidoro de Sevilla'''}}) (c.560- April 4, 636), was Archbishop of Seville for more than three decades, [[theology|theologian]], the last of the Western Latin Fathers, and an encyclopaedist. Isidore has the reputation of being one of the great scholars of the early [[Middle Ages]]. At a time of disintegration of classical culture, and aristocratic violence and illiteracy, he championed education as a means of maintaining the integrity of the [[Christianity|Christian]] faith and fostering unity among the various cultural elements that made up the population of medieval [[Spain]]. |

| − | + | His ''Etymologies'', a vast encyclopedia of classical and modern knowledge, was one of the chief landmarks in glossography (the compilation of glossaries), and preserved many fragments of classical learning which otherwise would not have survived. Until the twelfth century brought translations from Arabic sources, it contained all that western Europeans knew of the works of [[Aristotle]] and other [[ancient Greece|Greeks]], and it was an important reference book for many centuries. | |

| + | |||

| + | All the later medieval history-writing of [[Spain]] was based on Isidore’s ''Historia de Regibus Gothorum, Vandalorum et Suevorum (History of the reigns of the Goths, Vandals, and Suevi''). | ||

==Life== | ==Life== | ||

| − | ===Childhood and | + | ===Childhood and Education=== |

| − | Isidore | + | A biography of Isidore supposedly written in the thirteenth century by Lucas Tudensis (in the ''Acta Sanctorum''), is mostly myth and cannot be trusted. Isidore’s family originated in Cartagena; they were orthodox [[Roman Catholicism|Catholic]] and probably Roman, and probably held some power and influence. His parents were Severianus and Theodora. His elder brother, Leander of Seville, was his immediate predecessor in the Catholic Metropolitan See of Seville, and while in office opposed King Liuvigild. A younger brother, Fulgentius, was awarded the Bishopric of Astigi at the start of the new reign of Catholic Reccared. His sister Florentina was a nun, and is said to have ruled over forty convents and one thousand religious. Isidore's parents died while he was young, leaving him in the care of his older brother, Leander. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Isidore received his elementary education in the Cathedral school of Seville, the first of its kind in Spain, where the ''trivium'' and ''quadrivium'' were taught by a body of learned men. In a remarkably short time Isidore mastered [[Latin]], [[Greek]], and [[Hebrew]]. It is not known whether he ever embraced monastic life or not, but he esteemed the monastic orders highly. On his elevation to the episcopate, he immediately constituted himself protector of the monks and in 619, he pronounced anathema against any ecclesiastic who should in any way molest the monasteries. | |

| − | Isidore | + | [[Image:SanIsidoroBibNac.JPG|thumb|left|Statue of Isidore of Seville, outside of the Biblioteca Nacional de España, in [[Madrid]].]] |

| − | |||

===Bishop of Seville=== | ===Bishop of Seville=== | ||

| − | On the death of Leander, Isidore succeeded to the See of Seville. | + | On the death of Leander, around 600 C.E., Isidore succeeded to the See of Seville, a post which he held until the end of his life. He was a respected figure in the Church, as can be seen from the introduction to his works written by Braulio, bishop of Saragossa: |

| + | "''Isidore, a man of greate distinction, bishop of the church of Seville, successor and brother of bishop Leander, flourished from the time of Emperor Maurice and King Reccared. In him antiquity reasserted itself—or rather, our time laid in him a picture of the wisdom of antiquity: a man practiced in every form of speech, he adapted himself in the quality of his words to the ignorant and the learned, and was distinguished for unequalled eloquence when there was fit opportunity. Furthermore, the intelligent reader will be able to understand easily from his diversified studies and the works he has completed, how great was his wisdom''." (Brehaut, p. 23) | ||

| − | His | + | His forty years in office was a period of disintegration and transition. For almost two centuries the [[Goths]] had been in full control of Spain, and the ancient institutions and classic learning of the [[Roman Empire]] were fast disappearing under their barbarous manners and contempt of learning. A new civilization was beginning to evolve in Spain from the blending racial elements that made up its population. Realizing that the spiritual as well as the material well-being of the nation depended on the full assimilation of the foreign elements, Isidore took on the task of welding the various peoples who made up the Hispano-Gothic kingdom into a homogeneous nation, using the resources of religion and education. He succeeded in eradicating [[Arianism]], which had taken deep root among the [[Visigoths]], the new heresy of [[Acephales]] was completely stifled at the very outset, and religious discipline was strengthened. |

| − | + | ===Second Synod of Seville (November 618 or 619)=== | |

| − | + | Isidore presided over the Second Council of Seville, begun November 13, 619, in the reign of Sisebur. The bishops of Gaul and Narbonne attended, as well as the Spanish prelates. The Council's Acts fully set forth the nature of Christ, countering Arian conceptions. | |

| − | Isidore presided over the Second Council of Seville, begun | ||

===Fourth National Council of Toledo === | ===Fourth National Council of Toledo === | ||

| − | At this council, begun | + | At this council, begun December 5, 633, all the bishops of Spain were in attendance. St. Isidore, though far advanced in years, presided over its deliberations, and was the originator of most of its enactments. The council probably expressed with tolerable accuracy the mind and influence of Isidore. The church was to be free and independent, yet bound in solemn allegiance to the acknowledged king; nothing was said of allegiance to the [[Pope|bishop of Rome]]. The council decreed union between church and state, toleration of [[Judaism|Jews]], and uniformity in the Spanish Mass. Isidore successfully continued Leander's conversion of the Visigoths from Arianism (the heretical doctrine teaching that the Son was neither equal with God the Father nor eternal) to orthodox Christianity. |

| − | + | Trhough the influence of Isidore, the Fourth National Council of Toledo promulgated a decree commanding and requiring all bishops to establish seminaries in their Cathedral Cities, along the lines of the school associated with Isidore in Seville. Within his own jurisdiction, Isidore had developed an educational system to counteract the growing influence of Gothic barbarism, prescribing the study of Greek and [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]] as well as the liberal arts, and encouraging the study of [[law]] and [[medicine]]. Through the authority of the fourth council all the bishops of the kingdom were obliged to follow the same policy of education. | |

| − | + | ==Thought and Works== | |

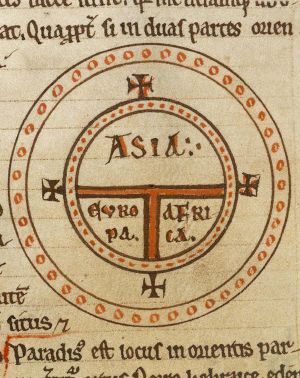

| + | [[Image:Diagrammatic T-O world map - 12th century.jpg|thumb|The medieval T-O map represents the inhabitated world as described by Isidore in his ''Etymologiae''. He assumes the Earth to be flat.]] | ||

| + | Isidore introduced Aristotle to his countrymen long before the Arab scholars began to appreciate early Greek philosophy. He was the first [[Christianity|Christian]] writer to attempt the compilation of a summa of universal knowledge, his most important work, the ''Etymologiae.'' Isidore's Latin style in the ‘’Etymologiae‘’ and other works, was affected by local Visigothic traditions and cannot be said to be classical. It contained most of the imperfections peculiar to the ages of transition, and particularly revealed a growing Visigothic influence, containing hundreds of recognizably Spanish words (his eighteenth-century editor Faustino Arévalo identified 1,640 of them). Isidore can possibly be characterized as the world's last native speaker of [[Latin]] and perhaps the world's first native speaker of [[Spanish language|Spanish]]. His great learning and his defense of education before the rising tide of Gothic barbarism were important to the development of Spanish culture. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===''Etymologiae''=== | ===''Etymologiae''=== | ||

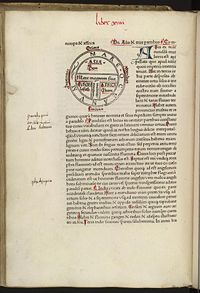

| − | + | [[Image:Etymologiae Guntherus Ziner 1472.jpg|thumb|200px|First printed edition of 1472 (by Guntherus Zainer, Augsburg), title page of book 14 (''de terra et partibus''), illustrated with a T and O map.]] | |

| − | + | '''''Etymologiae''''' (or '''''Origines''''') was an encyclopedia, compiled by Isidore of Seville at the urging of his friend Braulio, Bishop of Saragossa. At the end of his life, Isidore sent his ''codex inemendatus'' ("unedited book"), to Braulio, but it seems to have begun circulating before Braurio was able to revise it and issue it, with a dedication to the late King Sisebur. As a result, three families of texts have been distinguished, including a "compressed" text with many omissions, and an expanded text with interpolations. | |

| + | |||

| + | This encyclopedia, the first known to have been compiled in Western civilization, epitomized all learning, ancient as well as modern, in twenty volumes consisting of four-hundred-and-forty-eight chapters. It preserved many fragments of classical learning which otherwise would not have survived, but because Isidore’s work was so highly regarded, it also had the deleterious effect of superseding the use of many individual works which were not recopied and have therefore been lost. | ||

| − | + | ''Etymologiae'' presented in abbreviated form much of the learning of antiquity that Christians thought worth preserving. [[etymology|Etymologies]], often very learned and far-fetched, a favorite ''trope'' (theme) of Antiquity, formed the subject of just one of the encyclopedia's twenty books. Isidore's vast encyclopedia included subjects from [[theology]] to furniture and provided a rich source of classical lore and learning for medieval writers. | |

| − | ===Other | + | "''An editor's enthusiasm is soon chilled by the discovery that Isidore's book is really a mosaic of pieces borrowed from previous writers, sacred and profane, often their 'ipsa verba' without alteration''," W. M. Lindsay noted in 1911, having recently edited Isidore for the Clarendon Press,<ref>''Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi Etymologiarum Sive Originum Libri XX'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press), 1911; see W. M. Lindsay, "The Editing of Isidore Etymologiae" ''The Classical Quarterly'' '''5'''.1 (January 1911, pp. 42-53( p 42.</ref> with the further observation, however, that a portion of the texts quoted have otherwise been lost. In all, Isidore quoted from one-hundred-and-fifty-four authors, both Christian and [[paganism|pagan]]. Many of the Christian authors he read in the originals; of the pagans, many he consulted in current compilations. In the second book, dealing with dialectic and rhetoric, Isidore is heavily indebted to translations from the Greek by [[Boethius]], and in treating logic, [[Cassiodorus]], who provided the gist of Isidore's treatment of arithmetic in ''Book III''. Caelius Aurelianus contributes generously to that part of the fourth book which deals with medicine. Isidore's view of Roman law in the fifth book is viewed through the lens of the Visigothic compendiary called the ''Breviary of Alaric'', which was based on the ''Code of Theodosius,'' which Isidore never saw. Through Isidore's condensed paraphrase a third-hand memory of Roman law passed to the Early Middle Ages. Lactantius is the author most extensively quoted in the eleventh book, concerning man. The twelfth, thirteenth, and fourteenth books are largely based on the writings of [[Pliny]] and [[Solinus]]; whilst the lost ''Prata'' of Suetonius, which can be partly pieced together from its quoted passages in ''Etymolgiae'', seems to have inspired the general plan of the "Etymologiae", as well as many of its details. |

| − | + | ||

| − | * | + | Bishop Braulio, to whom Isidore dedicated it and sent it for correction, divided it into its twenty books. |

| + | |||

| + | Unfortunately Isidore misread his classical sources and said that the earth was flat (inventing the “T and O map” concept, as it is now known). For several centuries this nearly came to replace the traditional view that the earth was round, as stated for example by [[Bede]] in ''The Reckoning of Time''. A stylized map based on ''Etymologiae'' was printed in 1472 in Augsburg, featuring the world as a wheel. The continent [[Asia]] is peopled by descendants of Sem or Shem, Africa by descendants of Ham, and Europe by descendants of Japheth, the three sons of [[Noah]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The fame of "Etymologiae" inspired an abundance of encyclopedic writing during the subsequent centuries of the [[Middle Ages]]. It was the most popular compendium in medieval libraries, and was printed in at least ten editions between 1470 and 1530, demonstrating Isidore's continued popularity during the [[Renaissance]], which rivaled that of [[Vincent of Beauvais]]. Until the twelfth century brought translations from Arabic sources, Isidore transmitted what western Europeans remembered of the works of [[Aristotle]] and other Greeks, although he understood only a limited amount of Greek. The ''Etymologiae'' was much copied, particularly into medieval bestiaries. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Other Works=== | ||

| + | Isidore’s ''Historia de Regibus Gothorum, Vandalorum et Suevorum'' [''History of the reigns of the Goths, Vandals, and Suevi''] continues to be a useful source for the early history of Spain. Isidore also wrote treatises on theology, language, natural history, and other subjects. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Isidore’s other works include | ||

| + | * ''Chronica Majora'' (a universal history) | ||

*''De differentiis verborum'', which amounts to brief theological treatise on the doctrine of the Trinity, the nature of Christ, of Paradise, angels, and men. | *''De differentiis verborum'', which amounts to brief theological treatise on the doctrine of the Trinity, the nature of Christ, of Paradise, angels, and men. | ||

*a ''History of the Goths'' | *a ''History of the Goths'' | ||

*''On the Nature of Things'' (not the poem of [[Lucretius]]) | *''On the Nature of Things'' (not the poem of [[Lucretius]]) | ||

| − | *a book of astronomy and natural history dedicated to the Visigothic king | + | *a book of astronomy and natural history dedicated to the Visigothic king Sisebut |

*''Questions on the Old Testament''. | *''Questions on the Old Testament''. | ||

*a mystical treatise on the allegorical meanings of numbers | *a mystical treatise on the allegorical meanings of numbers | ||

| Line 87: | Line 96: | ||

*Sententiae libri tres ([http://www.cesg.unifr.ch/cesg-cgi/kleioc/g0010/exec/pagesmaframe/%22csg-0228_001.jpg%22/segment/%22body%22 Cod. Sang. 228], 9th c.) | *Sententiae libri tres ([http://www.cesg.unifr.ch/cesg-cgi/kleioc/g0010/exec/pagesmaframe/%22csg-0228_001.jpg%22/segment/%22body%22 Cod. Sang. 228], 9th c.) | ||

| − | == | + | ==Reputation== |

| − | Isidore was the last of the ancient Christian | + | Isidore was the last of the ancient Christian philosophers, and the last of the great Latin Church Fathers. He was undoubtedly the most learned man of his age and exercised a far-reaching influence on the educational life of the [[Middle Ages]]. His contemporary and friend, Braulio, Bishop of Saragossa, regarded him as a man raised up by God to save the Spanish people from the tidal wave of barbarism that threatened to inundate the ancient civilization of Spain. The Eighth Council of Toledo (653) recorded its admiration of his character in these glowing terms: "''The extraordinary doctor, the latest ornament of the Catholic Church, the most learned man of the latter ages, always to be named with reverence, Isidore".'' This tribute was endorsed by the Fifteenth Council of Toledo, held in 688. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | In [[Dante]]'s Paradise (''Divine Comedy '' X.130), he is mentioned among theologians and doctors of the church alongside the Scot, Richard of St. Victor, and the Englishman [[Bede]]. | |

| − | * | + | |

| + | Isidore was canonized as a saint by the [[Roman Catholicism|Roman Catholic Church]] in 1598 and declared a Doctor of the Church in 1722. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Manuscripts of Etymologiae == | ||

| + | *[[St. Gall Abbey library]] | ||

| + | **[http://www.cesg.unifr.ch/cesg-cgi/kleioc/g0010/exec/pagesmaframe/%22csg-0232_001.jpg%22/segment/%22body%22 Cod. Sang. 232] lib. XI-XX (9th c.) | ||

| + | **[http://www.cesg.unifr.ch/cesg-cgi/kleioc/g0010/exec/pagesmaframe/%22csg-0237_001.jpg%22/segment/%22body%22 Cod. Sang. 237] (9th c.) | ||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Brehaut, Ernest. 1964. ''An encyclopedist of the Dark Ages, Isidore of Seville''. New York: B. Franklin. OCLC: 336621 | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Henderson, John. 2006. ''The medieval world of Isidore Seville''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN: 0521867401 9780521867405 9780521867405 0521867401 | ||

| + | *Isidore, and Stephen A. Barney. 2006. ''The etymologies of Isidore of Seville''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN: 0521837499 9780521837491 | ||

| + | *Isidore, Guido Donini, and Gordon B. Ford. 1970. ''Isidore of Seville's History of the Goths, Vandals, and Suevi.'' Leiden: E.J. Brill. OCLC: 94161 | ||

| − | + | *Macfarlane, Katherine Nell. 1980. ''Isidore of Seville on the pagan gods'' (Origines VIII.11). Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN: 0871697033 9780871697035 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| + | *[http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Isidore/home.html ''Etymologiae''] at [[LacusCurtius]] | ||

| + | *[http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/isidore.html ''Etymologiae''] at [[The Latin Library]] | ||

| + | *[http://bestiary.ca/etexts/brehaut1912/brehaut%20-%20encyclopedist%20of%20the%20dark%20ages.pdf Summary of contents in English] (starts on page 57) | ||

*[http://www.st-isidore.org Order of St. Isidore of Seville] | *[http://www.st-isidore.org Order of St. Isidore of Seville] | ||

*[http://www.ccel.org/w/wace/biodict/htm/TOC.htm Henry Wace, ''Dictionary of Christian Biography''] | *[http://www.ccel.org/w/wace/biodict/htm/TOC.htm Henry Wace, ''Dictionary of Christian Biography''] | ||

| Line 120: | Line 143: | ||

[[Category:Medieval writers]] | [[Category:Medieval writers]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Credit|97784578}} | {{Credit|97784578}} | ||

Revision as of 23:35, 5 March 2007

- See Isidore and Isidro for namesakes.

| Saint Isidore of Seville | |

|---|---|

| Bishop, Doctor of the Church | |

| Born | c.560 at Cartagena, Spain |

| Died | April 4, 636 at Seville, Spain |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church |

| Feast | April 4 |

| Attributes | bees; bishop holding a pen while surrounded by a swarm of bees; bishop standing near a beehive; old bishop with a prince at his feet; pen; priest or bishop with pen and book; with Saint Leander, Saint Fulgentius, and Saint Florentina; with his Etymologia |

| Patronage | students |

| Saints Portal |

Saint Isidore of Seville (Spanish: San Isidro or San Isidoro de Sevilla) (c.560- April 4, 636), was Archbishop of Seville for more than three decades, theologian, the last of the Western Latin Fathers, and an encyclopaedist. Isidore has the reputation of being one of the great scholars of the early Middle Ages. At a time of disintegration of classical culture, and aristocratic violence and illiteracy, he championed education as a means of maintaining the integrity of the Christian faith and fostering unity among the various cultural elements that made up the population of medieval Spain.

His Etymologies, a vast encyclopedia of classical and modern knowledge, was one of the chief landmarks in glossography (the compilation of glossaries), and preserved many fragments of classical learning which otherwise would not have survived. Until the twelfth century brought translations from Arabic sources, it contained all that western Europeans knew of the works of Aristotle and other Greeks, and it was an important reference book for many centuries.

All the later medieval history-writing of Spain was based on Isidore’s Historia de Regibus Gothorum, Vandalorum et Suevorum (History of the reigns of the Goths, Vandals, and Suevi).

Life

Childhood and Education

A biography of Isidore supposedly written in the thirteenth century by Lucas Tudensis (in the Acta Sanctorum), is mostly myth and cannot be trusted. Isidore’s family originated in Cartagena; they were orthodox Catholic and probably Roman, and probably held some power and influence. His parents were Severianus and Theodora. His elder brother, Leander of Seville, was his immediate predecessor in the Catholic Metropolitan See of Seville, and while in office opposed King Liuvigild. A younger brother, Fulgentius, was awarded the Bishopric of Astigi at the start of the new reign of Catholic Reccared. His sister Florentina was a nun, and is said to have ruled over forty convents and one thousand religious. Isidore's parents died while he was young, leaving him in the care of his older brother, Leander.

Isidore received his elementary education in the Cathedral school of Seville, the first of its kind in Spain, where the trivium and quadrivium were taught by a body of learned men. In a remarkably short time Isidore mastered Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. It is not known whether he ever embraced monastic life or not, but he esteemed the monastic orders highly. On his elevation to the episcopate, he immediately constituted himself protector of the monks and in 619, he pronounced anathema against any ecclesiastic who should in any way molest the monasteries.

Bishop of Seville

On the death of Leander, around 600 C.E., Isidore succeeded to the See of Seville, a post which he held until the end of his life. He was a respected figure in the Church, as can be seen from the introduction to his works written by Braulio, bishop of Saragossa: "Isidore, a man of greate distinction, bishop of the church of Seville, successor and brother of bishop Leander, flourished from the time of Emperor Maurice and King Reccared. In him antiquity reasserted itself—or rather, our time laid in him a picture of the wisdom of antiquity: a man practiced in every form of speech, he adapted himself in the quality of his words to the ignorant and the learned, and was distinguished for unequalled eloquence when there was fit opportunity. Furthermore, the intelligent reader will be able to understand easily from his diversified studies and the works he has completed, how great was his wisdom." (Brehaut, p. 23)

His forty years in office was a period of disintegration and transition. For almost two centuries the Goths had been in full control of Spain, and the ancient institutions and classic learning of the Roman Empire were fast disappearing under their barbarous manners and contempt of learning. A new civilization was beginning to evolve in Spain from the blending racial elements that made up its population. Realizing that the spiritual as well as the material well-being of the nation depended on the full assimilation of the foreign elements, Isidore took on the task of welding the various peoples who made up the Hispano-Gothic kingdom into a homogeneous nation, using the resources of religion and education. He succeeded in eradicating Arianism, which had taken deep root among the Visigoths, the new heresy of Acephales was completely stifled at the very outset, and religious discipline was strengthened.

Second Synod of Seville (November 618 or 619)

Isidore presided over the Second Council of Seville, begun November 13, 619, in the reign of Sisebur. The bishops of Gaul and Narbonne attended, as well as the Spanish prelates. The Council's Acts fully set forth the nature of Christ, countering Arian conceptions.

Fourth National Council of Toledo

At this council, begun December 5, 633, all the bishops of Spain were in attendance. St. Isidore, though far advanced in years, presided over its deliberations, and was the originator of most of its enactments. The council probably expressed with tolerable accuracy the mind and influence of Isidore. The church was to be free and independent, yet bound in solemn allegiance to the acknowledged king; nothing was said of allegiance to the bishop of Rome. The council decreed union between church and state, toleration of Jews, and uniformity in the Spanish Mass. Isidore successfully continued Leander's conversion of the Visigoths from Arianism (the heretical doctrine teaching that the Son was neither equal with God the Father nor eternal) to orthodox Christianity.

Trhough the influence of Isidore, the Fourth National Council of Toledo promulgated a decree commanding and requiring all bishops to establish seminaries in their Cathedral Cities, along the lines of the school associated with Isidore in Seville. Within his own jurisdiction, Isidore had developed an educational system to counteract the growing influence of Gothic barbarism, prescribing the study of Greek and Hebrew as well as the liberal arts, and encouraging the study of law and medicine. Through the authority of the fourth council all the bishops of the kingdom were obliged to follow the same policy of education.

Thought and Works

Isidore introduced Aristotle to his countrymen long before the Arab scholars began to appreciate early Greek philosophy. He was the first Christian writer to attempt the compilation of a summa of universal knowledge, his most important work, the Etymologiae. Isidore's Latin style in the ‘’Etymologiae‘’ and other works, was affected by local Visigothic traditions and cannot be said to be classical. It contained most of the imperfections peculiar to the ages of transition, and particularly revealed a growing Visigothic influence, containing hundreds of recognizably Spanish words (his eighteenth-century editor Faustino Arévalo identified 1,640 of them). Isidore can possibly be characterized as the world's last native speaker of Latin and perhaps the world's first native speaker of Spanish. His great learning and his defense of education before the rising tide of Gothic barbarism were important to the development of Spanish culture.

Etymologiae

Etymologiae (or Origines) was an encyclopedia, compiled by Isidore of Seville at the urging of his friend Braulio, Bishop of Saragossa. At the end of his life, Isidore sent his codex inemendatus ("unedited book"), to Braulio, but it seems to have begun circulating before Braurio was able to revise it and issue it, with a dedication to the late King Sisebur. As a result, three families of texts have been distinguished, including a "compressed" text with many omissions, and an expanded text with interpolations.

This encyclopedia, the first known to have been compiled in Western civilization, epitomized all learning, ancient as well as modern, in twenty volumes consisting of four-hundred-and-forty-eight chapters. It preserved many fragments of classical learning which otherwise would not have survived, but because Isidore’s work was so highly regarded, it also had the deleterious effect of superseding the use of many individual works which were not recopied and have therefore been lost.

Etymologiae presented in abbreviated form much of the learning of antiquity that Christians thought worth preserving. Etymologies, often very learned and far-fetched, a favorite trope (theme) of Antiquity, formed the subject of just one of the encyclopedia's twenty books. Isidore's vast encyclopedia included subjects from theology to furniture and provided a rich source of classical lore and learning for medieval writers.

"An editor's enthusiasm is soon chilled by the discovery that Isidore's book is really a mosaic of pieces borrowed from previous writers, sacred and profane, often their 'ipsa verba' without alteration," W. M. Lindsay noted in 1911, having recently edited Isidore for the Clarendon Press,[1] with the further observation, however, that a portion of the texts quoted have otherwise been lost. In all, Isidore quoted from one-hundred-and-fifty-four authors, both Christian and pagan. Many of the Christian authors he read in the originals; of the pagans, many he consulted in current compilations. In the second book, dealing with dialectic and rhetoric, Isidore is heavily indebted to translations from the Greek by Boethius, and in treating logic, Cassiodorus, who provided the gist of Isidore's treatment of arithmetic in Book III. Caelius Aurelianus contributes generously to that part of the fourth book which deals with medicine. Isidore's view of Roman law in the fifth book is viewed through the lens of the Visigothic compendiary called the Breviary of Alaric, which was based on the Code of Theodosius, which Isidore never saw. Through Isidore's condensed paraphrase a third-hand memory of Roman law passed to the Early Middle Ages. Lactantius is the author most extensively quoted in the eleventh book, concerning man. The twelfth, thirteenth, and fourteenth books are largely based on the writings of Pliny and Solinus; whilst the lost Prata of Suetonius, which can be partly pieced together from its quoted passages in Etymolgiae, seems to have inspired the general plan of the "Etymologiae", as well as many of its details.

Bishop Braulio, to whom Isidore dedicated it and sent it for correction, divided it into its twenty books.

Unfortunately Isidore misread his classical sources and said that the earth was flat (inventing the “T and O map” concept, as it is now known). For several centuries this nearly came to replace the traditional view that the earth was round, as stated for example by Bede in The Reckoning of Time. A stylized map based on Etymologiae was printed in 1472 in Augsburg, featuring the world as a wheel. The continent Asia is peopled by descendants of Sem or Shem, Africa by descendants of Ham, and Europe by descendants of Japheth, the three sons of Noah.

The fame of "Etymologiae" inspired an abundance of encyclopedic writing during the subsequent centuries of the Middle Ages. It was the most popular compendium in medieval libraries, and was printed in at least ten editions between 1470 and 1530, demonstrating Isidore's continued popularity during the Renaissance, which rivaled that of Vincent of Beauvais. Until the twelfth century brought translations from Arabic sources, Isidore transmitted what western Europeans remembered of the works of Aristotle and other Greeks, although he understood only a limited amount of Greek. The Etymologiae was much copied, particularly into medieval bestiaries.

Other Works

Isidore’s Historia de Regibus Gothorum, Vandalorum et Suevorum [History of the reigns of the Goths, Vandals, and Suevi] continues to be a useful source for the early history of Spain. Isidore also wrote treatises on theology, language, natural history, and other subjects.

Isidore’s other works include

- Chronica Majora (a universal history)

- De differentiis verborum, which amounts to brief theological treatise on the doctrine of the Trinity, the nature of Christ, of Paradise, angels, and men.

- a History of the Goths

- On the Nature of Things (not the poem of Lucretius)

- a book of astronomy and natural history dedicated to the Visigothic king Sisebut

- Questions on the Old Testament.

- a mystical treatise on the allegorical meanings of numbers

- a number of brief letters.

- Sententiae libri tres (Cod. Sang. 228, 9th c.)

Reputation

Isidore was the last of the ancient Christian philosophers, and the last of the great Latin Church Fathers. He was undoubtedly the most learned man of his age and exercised a far-reaching influence on the educational life of the Middle Ages. His contemporary and friend, Braulio, Bishop of Saragossa, regarded him as a man raised up by God to save the Spanish people from the tidal wave of barbarism that threatened to inundate the ancient civilization of Spain. The Eighth Council of Toledo (653) recorded its admiration of his character in these glowing terms: "The extraordinary doctor, the latest ornament of the Catholic Church, the most learned man of the latter ages, always to be named with reverence, Isidore". This tribute was endorsed by the Fifteenth Council of Toledo, held in 688.

In Dante's Paradise (Divine Comedy X.130), he is mentioned among theologians and doctors of the church alongside the Scot, Richard of St. Victor, and the Englishman Bede.

Isidore was canonized as a saint by the Roman Catholic Church in 1598 and declared a Doctor of the Church in 1722.

Manuscripts of Etymologiae

- St. Gall Abbey library

- Cod. Sang. 232 lib. XI-XX (9th c.)

- Cod. Sang. 237 (9th c.)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brehaut, Ernest. 1964. An encyclopedist of the Dark Ages, Isidore of Seville. New York: B. Franklin. OCLC: 336621

- Henderson, John. 2006. The medieval world of Isidore Seville. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN: 0521867401 9780521867405 9780521867405 0521867401

- Isidore, and Stephen A. Barney. 2006. The etymologies of Isidore of Seville. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN: 0521837499 9780521837491

- Isidore, Guido Donini, and Gordon B. Ford. 1970. Isidore of Seville's History of the Goths, Vandals, and Suevi. Leiden: E.J. Brill. OCLC: 94161

- Macfarlane, Katherine Nell. 1980. Isidore of Seville on the pagan gods (Origines VIII.11). Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN: 0871697033 9780871697035

External links

- Etymologiae at LacusCurtius

- Etymologiae at The Latin Library

- Summary of contents in English (starts on page 57)

- Order of St. Isidore of Seville

- Henry Wace, Dictionary of Christian Biography

- Catholic Encyclopedia, 1913: 'Isidore of Seville'

- The Most Serene and Sovereign Order of Saint Isidore

- The Etymologiae (complete latin text)

- Jones, Peter. "Patron saint of the internet". The Telegraph, August 27, 2006 (Review of The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville, Cambridge University Press, 2006 (ISBN 0-521-83749-9))

- Shachtman, Noah. "Searchin' for the Surfer's Saint". Wired, January 25, 2002

This article incorporates text from the public-domain Catholic Encyclopedia of 1913.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi Etymologiarum Sive Originum Libri XX (Oxford: Clarendon Press), 1911; see W. M. Lindsay, "The Editing of Isidore Etymologiae" The Classical Quarterly 5.1 (January 1911, pp. 42-53( p 42.