Oberth, Hermann

| (19 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}}{{copyedited}} |

{{epname|Oberth, Hermann}} | {{epname|Oberth, Hermann}} | ||

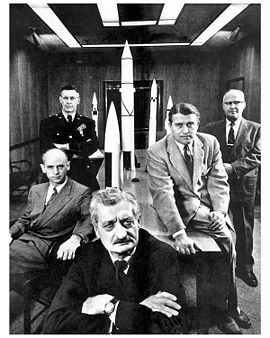

[[Image:AMBA Pioneers.jpg|270px|thumb|right|Oberth (in front) with fellow [[Army Ballistic Missile Agency|ABMA]] employees. Left to right: Dr. [[Ernst Stuhlinger]], Major General [[Holger Toftoy]], Oberth, Dr. [[Wernher von Braun]], and Dr. [[Robert Lusser]].]] | [[Image:AMBA Pioneers.jpg|270px|thumb|right|Oberth (in front) with fellow [[Army Ballistic Missile Agency|ABMA]] employees. Left to right: Dr. [[Ernst Stuhlinger]], Major General [[Holger Toftoy]], Oberth, Dr. [[Wernher von Braun]], and Dr. [[Robert Lusser]].]] | ||

| − | '''Hermann Julius Oberth''' (June 25, 1894 – December 28, 1989) was an [[Austria-Hungary|Austro-Hungarian]]-born, [[Germany|German]] and [[Romania]]n [[physicist]], | + | '''Hermann Julius Oberth''' (June 25, 1894 – December 28, 1989) was an [[Austria-Hungary|Austro-Hungarian]]-born, [[Germany|German]] and [[Romania]]n [[physicist]], whose writings in the 1920s sparked a surge of interest in the subject of space flight. He was among the first to write about the use of liquid propellants in rocketry. Oberth participated in the development of the German [[V-2 rocket]] during [[World War II]], and in the American space program after the war. |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | ==Biography== | ||

| + | ===Early years=== | ||

| − | + | Oberth was the son of Dr. [[Julius Oberth]], the head of a [[Transylvanian Saxons|Saxon]] family in the city of Schäßburg (present-day [[Sighişoara]]), in Transylvania. On Oberth's tenth birthday, he was given a telescope, and this gift triggered some speculation on his part as to how one might travel to the moon. In high school, Oberth became fascinated with the field in which he was to make his mark through the writings of [[Jules Verne]], especially ''[[From the Earth to the Moon]]'' and ''Around the Moon,'' re-reading them to the point of memorization. Influenced by Verne's books and ideas, Oberth constructed his first [[model rocket]] at age 14. In his youthful experiments, he arrived independently at the concept of the [[multistage rocket]], but lacked the resources to pursue his idea on any but a theoretical level. He did, however, make calculations demonstrating that the canon that launches the characters of Jules Verne's novel into space would kill its passengers because of the high acceleration required to reach the velocity necessary to escape the earth's pull. Oberth suggested that a rocket could be used to make escape from terrestrial gravity a non-lethal event. | |

| − | + | In spite of the distractions that his investigations into rocketry created, Oberth continued his studies, and passed his final exams with accolades, graduating in 1912. | |

| − | + | ===University training=== | |

| + | Later that same year, Oberth went to [[Munich]] to study medicine, but at the outbreak of [[World War I]] he was drafted in an [[German Empire|Imperial German]] infantry battalion and sent to the [[Eastern Front (World War I)|Eastern Front]]. In 1915, he was wounded, and was moved for treatment to a medical unit in his hometown. Here he initially conducted a series of experiments concerning [[weightlessness]] and later resumed his rocket designs. In 1917, he showed designs of a missile using liquid propellant with a range of 180 miles to [[Hermann von Stein]], the [[Prussian Minister of War]].<ref>Le Monde, ''Mort de Hermann Oberth, Pionnier de la conquête spatiale (The Death of Hermann Oberth, Space Conquest Pioneer).''</ref> This did not generate the interest that he had hoped, and as a result, Oberth turned to the development of peaceful uses of rocketry and space travel. | ||

| − | On July 6, 1918 he married Mathilde Hummel, with whom he had four children, among them a son who died at the front during [[World War II]], and a daughter who also died during the war, when a [[liquid oxygen]] plant exploded in a workplace accident in August 1944. In 1919 he moved once again to Germany, this time to study physics, initially in [[Munich]] and later in [[Göttingen]]. | + | On July 6, 1918, he married Mathilde Hummel, with whom he had four children, among them a son who died at the front during [[World War II]], and a daughter who also died during the war, when a [[liquid oxygen]] plant exploded in a workplace accident in August 1944. In 1919, he moved once again to Germany, this time to study physics, initially in [[Munich]] and later in [[Göttingen]], Heidelberg, and Klausenburg, in Transylvania. |

| − | + | ===Seminal work on rocketry=== | |

| + | Oberth's 1922 doctoral dissertation on rocket science was at first rejected. Phillip Lenard, the Nobel laureate, felt that the work was excellent, but too interdisciplinary to qualify as a physics dissertation. Another scientist likewise praised it, but said it was unacceptable as an astronomical work. Oberth commented later that he made the deliberate choice not to write another doctoral dissertation. "I refrained from writing another one," Oberth said, "thinking to myself: 'Never mind, I will prove that I am able to become a greater scientist than some of you, even without the title of doctor.'"<ref>Kiosek.com, [http://www.kiosek.com/oberth/ Hermann Oberth, Father of Space Travel.] Retrieved October 9, 2007.</ref> He criticized the [[Education in Germany|German system of education]], saying "Our educational system is like an automobile which has strong rear lights, brightly illuminating the past. But looking forward things are barely discernible." Oberth submitted the paper to qualify for a teaching degree, and was finally awarded with the title of doctor in physics by professor Augustin Maior, at [[Babeş-Bolyai University]], [[Cluj-Napoca]] ([[Romania]]), on May 23, 1923. He had the 92-page thesis privately published at the end of 1923, as the controversial ''Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen'' ''(By Rocket into Planetary Space)''. | ||

| − | + | ''By Rocket into Planetary Space'' became an immensely popular work that influenced the future of rocketry and catapulted a vision of space travel into the public imagination. In this work, Oberth discusses the benefits of liquid fuel rocketry and many aspects of space flight. While somewhat technical in nature, the dissertation was later popularized and publicized by other writers, bringing almost immediate fame to Oberth, who in 1924, took a teaching position at a high school in Transylvania to support his family. | |

| + | ===Society for Space Flight=== | ||

| + | Inspired by Oberth's writings, German rocket researchers and enthusiasts, in 1927, established an amateur rocket group called the ''[[Verein für Raumschiffahrt]]'' (VfR--"Society for Space Flight"). Oberth joined the group, and acted as something of a mentor to its members. | ||

| − | + | In 1928 and 1929, Oberth worked in [[Berlin]] as scientific consultant on the first film ever to have scenes set in space, ''[[Frau im Mond]]'' ("The Woman in the Moon"), directed at [[Universum Film AG]] by [[Fritz Lang]]. The film was of enormous value in popularizing the idea of rocket science. Oberth's main task was to build and launch a rocket as a publicity event prior to the film's premiere. He was, however, unable to complete more than a movie prop, and the payment negotiated by Lang for the actual missile launch was not forthcoming, leaving Oberth in a state of depression. But the film benefited immensely from the scientific imprimatur granted by its association with Oberth.<ref>Christopher Frayling, ''Mad, Bad and Dangerous? The Scientist and the Cinema'' (London: Reaktion, 2005), 72. ISBN 1861892551</ref> | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | Coinciding roughly with the film's 1929 premier, Oberth published a book-length work entitled ''Wege zur Raumschiffahrt'' ''(Ways to Spaceflight)'', which was an expansion of his 1923 thesis. As a result, Oberth won the first [[Robert Esnault-Pelterie|REP]]-[[André-Louis Hirsch|Hirsch]] Prize of the French Astronomical Society for his encouragement of astronautics.<ref>L. Blosset, ''L'Aerophile,'' ''Smithsonian Annals of Flight''. 10:11.</ref> | |

| − | In autumn 1929, Oberth | + | In autumn 1929, Oberth tested his first liquid fuel engine. He was helped in this experiment by his students at the [[Technical University of Berlin]], one of whom was [[Wernher von Braun]], who would later head Germany's [[World War II|wartime]] effort to create a ballistic missile. He conducted further engine tests in 1930.<ref>George Paul Sutton, ''History of Liquid Propellant Rocket Engines'' (Reston, Va: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2005), 73. ISBN 1563476495</ref> |

| − | + | ===The V-2=== | |

| + | For several years in the 1930s, Oberth taught physics and mathematics at the [[Stephan Ludwig Roth]] High School in [[Mediaş]], all the while remaining active in the VfR. | ||

| − | In 1950 | + | In 1938, the Oberth family left [[Sibiu]] for good, to settle in Germany, where he received a stipend from the University of Dresden for rocket research. In 1941, at the invitation of Von Braun, Oberth went to [[Peenemünde]] to work on the V-2, a weaponized rocket that was mass-produced toward the end of World War II, and used to much psychological effect on London. He was awarded the ''[[War Merit Cross|Kriegsverdienstkreuz I Klasse mit Schwertern]]'' (War Merit Cross 1st Class, with Swords) in 1943, for his "outstanding, courageous behavior … during the attack" of Peenemünde by [[Operation Crossbow|Operation Hydra]], the allied program to uncover and destroy Germany's ballistic missile capability.<ref>Frederick I. Ordway, III, ''The Rocket Team'' (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1979). ISBN 043455300X</ref> Oberth later worked on solid-propellant anti-aircraft rockets. At the end of the war, Oberth was detained, and then released, by Allied forces. Rather than joining the teams of German scientists that had been gathered together by both the United States and the Soviet Union after the war, he and his family moved to [[Feucht]], near [[Nuremberg]]. Oberth left for [[Switzerland]] in 1948, where he worked as an independent consultant and a writer. |

| + | |||

| + | ===Later years=== | ||

| + | In 1950, Oberth went on to [[Italy]], where he completed work he had begun earlier for the [[Marina Militare|Italian Navy]]. In 1953 he returned to Feucht to publish his book ''Menschen im Weltraum'' ''(Man in Space)'', in which he described his ideas for a space-based [[reflecting telescope]], a [[space station]], an electric spaceship, and [[space suit]]s. | ||

In the 1950s, Oberth offered his opinions regarding [[unidentified flying object]]s; he was a supporter of the [[extraterrestrial hypothesis]]. | In the 1950s, Oberth offered his opinions regarding [[unidentified flying object]]s; he was a supporter of the [[extraterrestrial hypothesis]]. | ||

| − | Oberth eventually came to work for his ex-student von Braun, developing space rockets in [[Huntsville, Alabama]] in the [[United States]] | + | Oberth eventually came to work for his ex-student von Braun, developing space rockets in [[Huntsville, Alabama]], in the [[United States]], from 1955 to 1959. Among other things, Oberth was involved in writing a study, ''The Development of Space Technology in the Next Ten Years.'' After his work at Huntsville, he went to Feucht, Germany, where he published his ideas on a lunar exploration vehicle, a "lunar catapult," and on "muffled" helicopters and airplanes. In 1960, in the United States again, he went to work for [[Convair]] as a technical consultant on the [[Atlas (rocket)|Atlas rocket]]. |

| − | + | Hermann Oberth retired in 1962, at the age of 68. From 1965 to 1967, he was a member of the [[far right]] [[National Democratic Party of Germany|National Democratic Party]]. In July 1969, he returned to the United States to witness the launch of the [[Saturn V]] rocket that carried the [[Apollo 11]] crew on the first landing mission to the [[Moon]].<ref>U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission, [http://www.centennialofflight.gov/essay/SPACEFLIGHT/oberth/SP2.htm Hermann Oberth.] Retrieved October 9, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | Hermann Oberth retired in 1962 at the age of 68. From 1965 to 1967 he was a member of the [[far right]] [[National Democratic Party of Germany|National Democratic Party]]. In July 1969, he returned to the | ||

The [[1973 oil crisis|1973 energy crisis]] inspired Oberth to look at alternative energy sources, including a plan for a [[Wind power|wind power station]] that could utilize the [[jet stream]]. However, his main interest in retirement was to turn to more abstract philosophical questions. Most notable among his several books from this period is ''Primer For Those Who Would Govern''. | The [[1973 oil crisis|1973 energy crisis]] inspired Oberth to look at alternative energy sources, including a plan for a [[Wind power|wind power station]] that could utilize the [[jet stream]]. However, his main interest in retirement was to turn to more abstract philosophical questions. Most notable among his several books from this period is ''Primer For Those Who Would Govern''. | ||

| − | Oberth died in Nuremberg, on December 28, 1989. | + | Oberth died in Nuremberg, on December 28, 1989. |

==Legacy== | ==Legacy== | ||

| − | Oberth | + | Oberth's accomplishments were more conceptual than actual. It was his early writing on the subject of rocketry that sparked the imagination of a generation of Germans who eventually developed the V-2 program. Their achievements ironically established the foundation for the U.S. space program, and led to the fulfillment of Oberth's dream—a manned flight to the Moon. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Oberth is memorialized by the [[Hermann Oberth Space Travel Museum]] in Feucht, and by the [[Hermann Oberth Society]], which brings together scientists, researchers, and astronauts from East and West to carry on his work in rocketry and space exploration. | |

==Books== | ==Books== | ||

| Line 55: | Line 60: | ||

*''Primer for Those Who Would Govern'' (1987) ISBN 0-914301-06-3 | *''Primer for Those Who Would Govern'' (1987) ISBN 0-914301-06-3 | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

| Line 65: | Line 66: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| + | * Ordway, Frederick I., III. 1979. ''The Rocket Team''. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, Publishers. ISBN 043455300X | ||

| + | * Rauschenbach, Boris V. 1994. ''Hermann Oberth: The Father of Space Flight 1894-1989''. New York: West Art Pub. ISBN 0914301144 | ||

| + | * Sutton, George Paul. 2006. ''History of Liquid Propellant Rocket Engines''. Reston, Va: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. ISBN 1563476495 | ||

| + | * Walters, Helen B. 1962. ''Hermann Oberth: Father of Space Travel.'' New York: Macmillan. | ||

| + | * Wegener, Peter P. 1996. ''The Peenemünde Wind Tunnels: A Memoir''. New Haven: Yale University Press. 36-39. ISBN 0300063679 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | * [http://www.oberth-museum.org/ The Hermann Oberth | + | All links retrieved December 21, 2017. |

| − | + | * [http://www.oberth-museum.org/index_e.html The Hermann Oberth Raumfahrt Museum]. | |

[[Category:Physical sciences]] | [[Category:Physical sciences]] | ||

Latest revision as of 10:20, 22 January 2024

Hermann Julius Oberth (June 25, 1894 – December 28, 1989) was an Austro-Hungarian-born, German and Romanian physicist, whose writings in the 1920s sparked a surge of interest in the subject of space flight. He was among the first to write about the use of liquid propellants in rocketry. Oberth participated in the development of the German V-2 rocket during World War II, and in the American space program after the war.

Biography

Early years

Oberth was the son of Dr. Julius Oberth, the head of a Saxon family in the city of Schäßburg (present-day Sighişoara), in Transylvania. On Oberth's tenth birthday, he was given a telescope, and this gift triggered some speculation on his part as to how one might travel to the moon. In high school, Oberth became fascinated with the field in which he was to make his mark through the writings of Jules Verne, especially From the Earth to the Moon and Around the Moon, re-reading them to the point of memorization. Influenced by Verne's books and ideas, Oberth constructed his first model rocket at age 14. In his youthful experiments, he arrived independently at the concept of the multistage rocket, but lacked the resources to pursue his idea on any but a theoretical level. He did, however, make calculations demonstrating that the canon that launches the characters of Jules Verne's novel into space would kill its passengers because of the high acceleration required to reach the velocity necessary to escape the earth's pull. Oberth suggested that a rocket could be used to make escape from terrestrial gravity a non-lethal event.

In spite of the distractions that his investigations into rocketry created, Oberth continued his studies, and passed his final exams with accolades, graduating in 1912.

University training

Later that same year, Oberth went to Munich to study medicine, but at the outbreak of World War I he was drafted in an Imperial German infantry battalion and sent to the Eastern Front. In 1915, he was wounded, and was moved for treatment to a medical unit in his hometown. Here he initially conducted a series of experiments concerning weightlessness and later resumed his rocket designs. In 1917, he showed designs of a missile using liquid propellant with a range of 180 miles to Hermann von Stein, the Prussian Minister of War.[1] This did not generate the interest that he had hoped, and as a result, Oberth turned to the development of peaceful uses of rocketry and space travel.

On July 6, 1918, he married Mathilde Hummel, with whom he had four children, among them a son who died at the front during World War II, and a daughter who also died during the war, when a liquid oxygen plant exploded in a workplace accident in August 1944. In 1919, he moved once again to Germany, this time to study physics, initially in Munich and later in Göttingen, Heidelberg, and Klausenburg, in Transylvania.

Seminal work on rocketry

Oberth's 1922 doctoral dissertation on rocket science was at first rejected. Phillip Lenard, the Nobel laureate, felt that the work was excellent, but too interdisciplinary to qualify as a physics dissertation. Another scientist likewise praised it, but said it was unacceptable as an astronomical work. Oberth commented later that he made the deliberate choice not to write another doctoral dissertation. "I refrained from writing another one," Oberth said, "thinking to myself: 'Never mind, I will prove that I am able to become a greater scientist than some of you, even without the title of doctor.'"[2] He criticized the German system of education, saying "Our educational system is like an automobile which has strong rear lights, brightly illuminating the past. But looking forward things are barely discernible." Oberth submitted the paper to qualify for a teaching degree, and was finally awarded with the title of doctor in physics by professor Augustin Maior, at Babeş-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca (Romania), on May 23, 1923. He had the 92-page thesis privately published at the end of 1923, as the controversial Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen (By Rocket into Planetary Space).

By Rocket into Planetary Space became an immensely popular work that influenced the future of rocketry and catapulted a vision of space travel into the public imagination. In this work, Oberth discusses the benefits of liquid fuel rocketry and many aspects of space flight. While somewhat technical in nature, the dissertation was later popularized and publicized by other writers, bringing almost immediate fame to Oberth, who in 1924, took a teaching position at a high school in Transylvania to support his family.

Society for Space Flight

Inspired by Oberth's writings, German rocket researchers and enthusiasts, in 1927, established an amateur rocket group called the Verein für Raumschiffahrt (VfR—"Society for Space Flight"). Oberth joined the group, and acted as something of a mentor to its members.

In 1928 and 1929, Oberth worked in Berlin as scientific consultant on the first film ever to have scenes set in space, Frau im Mond ("The Woman in the Moon"), directed at Universum Film AG by Fritz Lang. The film was of enormous value in popularizing the idea of rocket science. Oberth's main task was to build and launch a rocket as a publicity event prior to the film's premiere. He was, however, unable to complete more than a movie prop, and the payment negotiated by Lang for the actual missile launch was not forthcoming, leaving Oberth in a state of depression. But the film benefited immensely from the scientific imprimatur granted by its association with Oberth.[3]

Coinciding roughly with the film's 1929 premier, Oberth published a book-length work entitled Wege zur Raumschiffahrt (Ways to Spaceflight), which was an expansion of his 1923 thesis. As a result, Oberth won the first REP-Hirsch Prize of the French Astronomical Society for his encouragement of astronautics.[4]

In autumn 1929, Oberth tested his first liquid fuel engine. He was helped in this experiment by his students at the Technical University of Berlin, one of whom was Wernher von Braun, who would later head Germany's wartime effort to create a ballistic missile. He conducted further engine tests in 1930.[5]

The V-2

For several years in the 1930s, Oberth taught physics and mathematics at the Stephan Ludwig Roth High School in Mediaş, all the while remaining active in the VfR.

In 1938, the Oberth family left Sibiu for good, to settle in Germany, where he received a stipend from the University of Dresden for rocket research. In 1941, at the invitation of Von Braun, Oberth went to Peenemünde to work on the V-2, a weaponized rocket that was mass-produced toward the end of World War II, and used to much psychological effect on London. He was awarded the Kriegsverdienstkreuz I Klasse mit Schwertern (War Merit Cross 1st Class, with Swords) in 1943, for his "outstanding, courageous behavior … during the attack" of Peenemünde by Operation Hydra, the allied program to uncover and destroy Germany's ballistic missile capability.[6] Oberth later worked on solid-propellant anti-aircraft rockets. At the end of the war, Oberth was detained, and then released, by Allied forces. Rather than joining the teams of German scientists that had been gathered together by both the United States and the Soviet Union after the war, he and his family moved to Feucht, near Nuremberg. Oberth left for Switzerland in 1948, where he worked as an independent consultant and a writer.

Later years

In 1950, Oberth went on to Italy, where he completed work he had begun earlier for the Italian Navy. In 1953 he returned to Feucht to publish his book Menschen im Weltraum (Man in Space), in which he described his ideas for a space-based reflecting telescope, a space station, an electric spaceship, and space suits.

In the 1950s, Oberth offered his opinions regarding unidentified flying objects; he was a supporter of the extraterrestrial hypothesis.

Oberth eventually came to work for his ex-student von Braun, developing space rockets in Huntsville, Alabama, in the United States, from 1955 to 1959. Among other things, Oberth was involved in writing a study, The Development of Space Technology in the Next Ten Years. After his work at Huntsville, he went to Feucht, Germany, where he published his ideas on a lunar exploration vehicle, a "lunar catapult," and on "muffled" helicopters and airplanes. In 1960, in the United States again, he went to work for Convair as a technical consultant on the Atlas rocket.

Hermann Oberth retired in 1962, at the age of 68. From 1965 to 1967, he was a member of the far right National Democratic Party. In July 1969, he returned to the United States to witness the launch of the Saturn V rocket that carried the Apollo 11 crew on the first landing mission to the Moon.[7]

The 1973 energy crisis inspired Oberth to look at alternative energy sources, including a plan for a wind power station that could utilize the jet stream. However, his main interest in retirement was to turn to more abstract philosophical questions. Most notable among his several books from this period is Primer For Those Who Would Govern.

Oberth died in Nuremberg, on December 28, 1989.

Legacy

Oberth's accomplishments were more conceptual than actual. It was his early writing on the subject of rocketry that sparked the imagination of a generation of Germans who eventually developed the V-2 program. Their achievements ironically established the foundation for the U.S. space program, and led to the fulfillment of Oberth's dream—a manned flight to the Moon.

Oberth is memorialized by the Hermann Oberth Space Travel Museum in Feucht, and by the Hermann Oberth Society, which brings together scientists, researchers, and astronauts from East and West to carry on his work in rocketry and space exploration.

Books

- The Moon Car (1959)

- The Electric Spaceship (1960)

- Ways to Spaceflight (1929)

- Primer for Those Who Would Govern (1987) ISBN 0-914301-06-3

Notes

- ↑ Le Monde, Mort de Hermann Oberth, Pionnier de la conquête spatiale (The Death of Hermann Oberth, Space Conquest Pioneer).

- ↑ Kiosek.com, Hermann Oberth, Father of Space Travel. Retrieved October 9, 2007.

- ↑ Christopher Frayling, Mad, Bad and Dangerous? The Scientist and the Cinema (London: Reaktion, 2005), 72. ISBN 1861892551

- ↑ L. Blosset, L'Aerophile, Smithsonian Annals of Flight. 10:11.

- ↑ George Paul Sutton, History of Liquid Propellant Rocket Engines (Reston, Va: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2005), 73. ISBN 1563476495

- ↑ Frederick I. Ordway, III, The Rocket Team (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1979). ISBN 043455300X

- ↑ U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission, Hermann Oberth. Retrieved October 9, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ordway, Frederick I., III. 1979. The Rocket Team. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, Publishers. ISBN 043455300X

- Rauschenbach, Boris V. 1994. Hermann Oberth: The Father of Space Flight 1894-1989. New York: West Art Pub. ISBN 0914301144

- Sutton, George Paul. 2006. History of Liquid Propellant Rocket Engines. Reston, Va: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. ISBN 1563476495

- Walters, Helen B. 1962. Hermann Oberth: Father of Space Travel. New York: Macmillan.

- Wegener, Peter P. 1996. The Peenemünde Wind Tunnels: A Memoir. New Haven: Yale University Press. 36-39. ISBN 0300063679

External links

All links retrieved December 21, 2017.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.