Freyr

Freyr (sometimes anglicized Frey)[1] is one of the most important deities in Norse paganism and Norse mythology. Worshipped as a phallic fertility god, Freyr "bestows peace and pleasure on mortals". He rules over the rain, the shining of the sun and the produce of the fields.

Freyr is one of the Vanir, the son of the sea god Njörðr and brother of the love goddess Freyja. His forseen posterity was such that that gods gave him Álfheimr, the realm of the Elves, as a teething present. He is easily recognized in mythic tales and artwork by the presence of his enchanted blade, his "dwarf-made" war-boar Gullinbursti and his ship, Skíðblaðnir, which always had a favorable breeze and could be folded down and carried in a pouch when it was not being used. Finally, he was especially associated with Sweden and was seen as an ancestor of the Swedish royal house.[2]

Freyr in a Norse Context

As a Norse deity, Freyr belonged to a complex religious, mythological and cosmological belief system shared by the Scandinavian and Germanic peoples. This mythological tradition, of which the Scandinavian (and particularly Icelandic) sub-groups are best preserved, developed in the period from the first manifestations of religious and material culture in approximately 1000 B.C.E. until the Christianization of the area, a process that occurred primarily from 900-1200 C.E.[3] The tales recorded within this mythological corpus tend to exemplify a unified cultural focus on physical prowess and military might.

Within this framework, Norse cosmology postulates three separate "clans" of deities: the Aesir, the Vanir, and the Jotun. The distinction between Aesir and Vanir is relative, for the two are said to have made peace, exchanged hostages, intermarried and reigned together after a prolonged war, which the Aesir had finally won. In fact, the most major divergence between the two groups is in their respective areas of influence, with the Aesir representing war and conquest, and the Vanir representing exploration, fertility and wealth.[4] The Jotun, on the other hand, are seen as a generally malefic (though wise) race of giants who represented the primary adversaries of the Aesir and Vanir.

Freyr, the most widely revered of the Vanir, is a god of fertility and sexuality.

Characteristics

As mentioned above, Freyr was of Vanir stock, and was thus associated with fertility (and sexuality in general). As Adam of Bremen states, he is the god "who bestows peace and pleasure on mortals."[5] His importance is further attested by Snorri Sturluson, who introduces Freyr as one of the major Norse deities:

- Njördr in Nóatún begot afterward two children: the son was called Freyr, and the daughter Freyja; they were fair of face and mighty. Freyr is the most renowned of the aesir; he rules over the rain and the shining of the sun, and therewithal the fruit of the earth; and it is good to call on him for fruitful seasons and peace. He governs also the prosperity of men.[6]

Though he is described as the "most renowned of the Aesir," it should be noted that Snorri is simply using the term broadly, as he himself details Freyr's forcible joining of the Aesir as a hostage after the Aesir-Vanir war.[7] A similarly positive description of the god can also be found in the Lokasenna (part of the Poetic Edda):

- Frey is best

- of all the exalted gods

- in the Æsir's courts:

- no maid he makes to weep,

- no wife of man,

- and from bonds looses all.[8]

Further, Freyr's power (or importance) is also attested to by the fact that the gods gave him an entire realm (Álfheimr, the "World of the Elves") as a teething present:

- Alfheim the gods to Frey

- gave in days of yore

- for a tooth-gift.[9]

This association could also evidence a now-lost connection between the Vanir and the Elves.

Freyr is associated with three magical artifacts: an intelligent sword that never misses its target, a golden boar, and a fantastic ship (all of them dwarf-made). The ship, Skíðblaðnir, which always has a favorable breeze and which can be folded together like a napkin and carried in a pouch, is not heavily featured in any surviving myths. The boar, Gullinbursti, whose mane glows to illuminate the way for his owner, on the other hand, is ridden by the god to Balder's funeral.[10] Finally, his sword is eventually given to Skirnir (his page), which indirectly leads to the god's death at Ragnarök (see below).

Mythic Accounts

The Marriage of Freyr

One of the most frequently (re)told myths surrounding Freyr is the account of his courtship and marriage. Snorri Sturluson, in the Prose Edda, begins his version by describing the god's first glimpse of his eventual bride:

- It chanced one day that Freyr had gone to Hlidskjálf, and gazed over all the world; but when he looked over into the northern region, he saw on an estate a house great and fair. And toward this house went a woman; when she raised her hands and opened the door before her, brightness gleamed from her hands, both over sky and sea, and all the worlds were illumined of her. Gylfaginning XXXVII, Brodeur's translation

The woman was Gerðr, a beautiful giantess. Freyr immediately fell in love with her and became depressed and taciturn, feeling that he would die if he could not be united with his beloved. After a period of fruitless brooding, he finally deigned to describe his romantic woes to Skírnir, his foot-page. After bemoaning his broken-hearted state, the god entreated his servant to go forth and woo the giantess in his stead. Skirnir agreed, but noted that he would require his master's horse and sword to brave the dangers between their home and the giantess's abode.

- Then Skírnir answered thus: he would go on his errand, but Freyr should give him his own sword-which is so good that it fights of itself;- and Freyr did not refuse, but gave him the sword. Then Skírnir went forth and wooed the woman for him, and received her promise; and nine nights later she was to come to the place called Barrey, and then go to the bridal with Freyr. (Gylfaginning XXXVII, Brodeur's translation).

The transaction between Freyr and Skirnir is dealt with more extensively in the Eddic poem Skírnismál, where the god states:

- My steed I lend thee

- to lift thee o'er the weird

- ring of flickering flame,

- the sword also

- which swings itself,

- if wise be he who wields it. (Skírnismál 9, Hollander's translation).

The Skírnismál also provides further insight into the means of persuasion employed by Skirnir to encourage the giantess to return with him to his master. More specifically, when she refused his gifts and entreaties, he began to threaten her with magical curses until she relented (and agreed to the marriage):

- 26."With this magic wand bewitch thee I shall,

- my will, maiden, to do;

- where the sons of men will see thee no more,

- thither shalt thou!

- 27."On the eagle-hill shalt ever sit,

- aloof from the world, lolling toward Hel.

- To thee men shall be more loathsome far

- than to mankind the slimy snake.

- 28."An ugly sight, when out thou comest,

- even Hrimnir will stare at and every hind glare at,

- more widely known than the warder of gods,

- and shalt gape through the gate.

- (Skírnismál 26-28, Hollander's translation).

Despite the predominantly positive conclusion to this escapade, the loss of Freyr's sword was not without consequences. For instance, a later account describes a battle between Freyr and Beli (a giant), who the weaponless god ended up slaying with an antler.[11] More significantly, the loss of his sword is one of the reasons that Freyr falls to Surtr at Ragnarök (the battle at the end of time).

Freyr's Involvement in Ragnarök

During the Eschaton, Freyr, defending Asgard against the host of fire giants attacking from the south, will be killed by Surtr (the fire giant who rules over Muspelheim). Often, the god's loss is credited to the fact that he gave his magical sword to his servant. His death is described in Völuspá, the best known of the Eddic poems:

- Surtr moves from the south

- with the scathe of branches:[12]

- there shines from his sword

- the sun of Gods of the Slain.

- Stone peaks clash,

- and troll wives take to the road.

- Warriors tread the path from Hel,

- and heaven breaks apart.

- Then is fulfilled Hlín's

- second sorrow,

- when Óðinn goes

- to fight with the wolf [Fenris],

- and Beli's slayer [a poetic kenning for Freyr]

- bright, against Surtr.

- Then shall Frigg's

- sweet friend fall. Völuspá 50 - 51, Dronke's translation

More concisely, the Prose Edda states that "Freyr shall contend with Surtr, and a hard encounter shall there be between them before Freyr falls: it is to be his death that he lacks that good sword of his, which he gave to Skirnir."[13]

Euhemeristic Views of Freyr

While many of the gods in the Norse pantheon were seen to have an active relationship with humans individuals and societies (often as bestowers of favors), Freyr is somewhat unique for his putative relationship with the Swedish royal family. This euhemeristic attribution is evidenced in numerous sources, including the Íslendingabók, the Danish History of Saxo Grammaticus, and Snorri Sturluson's Yngling Saga.

In the most straightforward case, that of the Íslendingabók, Freyr is simply included in a genealogy of Swedish kings. This unquestioning historicism is echoed in Saxo's Gesta Danorum, which identifies Frø [a transliteration of Freyr] as the "king of Sweden" (rex Suetiae):

- About this time the Swedish ruler Frø, after killing Sivard, king of the Norwegians, removed the wives of Sivard's relatives to a brothel and exposed them to public prostitution. (Gesta Danorum 9, Fisher's translation.)

In a more detailed manner, Snorri Sturluson begins his epic history of Scandinavia with the Ynglinga saga, a euhemerized account of the Norse gods. Here, Odin and the Æsir are depicted as men from Asia who gain power through Odin's leadership skills and the clan's considerable prowess in war. These advantages were sorely tested when the All-Father declared war on the Vanir, as he underestimated the rival tribe's bravery and ferocity. This tactical misstep led to a costly and indecisive war, which was eventually concluded with a truce and sealed with the exchange of hostages. Two of the Vanir's hostages were Freyr and Njörðr, who were thereby sent to live with the Æsir.[14]

Over time, Odin made Njörðr and Freyr the priests of sacrifices, a post which earned them both respect and influence in Norse society. The Ynglinga saga then details Odin's conquest of the North, including his ultimate settlement in Sweden, where he ruled as king, collected taxes and maintained sacrifices. After Odin's death, Njörðr took the throne and ushered in an era of peace and good harvests (which came to be associated with his power). Eventually, Njörðr also fell ill and died, at which point

- Frey took the kingdom after Njord, and was called drot [a Scandinavian term for religious and political leaders] by the Swedes, and they paid taxes to him. He was, like his father, fortunate in friends and in good seasons. Frey built a great temple at Upsal, made it his chief seat, and gave it all his taxes, his land, and goods. Then began the Upsal domains, which have remained ever since. Then began in his days the Frode-peace [legendary kings associated with a period of prosperity]; and then there were good seasons, in all the land, which the Swedes ascribed to Frey, so that he was more worshipped than the other gods, as the people became much richer in his days by reason of the peace and good seasons. ... Frey was called by another name, Yngve;[15] and this name Yngve was considered long after in his race as a name of honour, so that his descendants have since been called Ynglinger. Frey fell into a sickness; and as his illness took the upper hand, his men took the plan of letting few approach him. In the meantime they raised a great mound, in which they placed a door with three holes in it. Now when Frey died they bore him secretly into the mound, but told the Swedes he was alive; and they kept watch over him for three years. They brought all the taxes into the mound, and through the one hole they put in the gold, through the other the silver, and through the third the copper money that was paid. Peace and good seasons continued. Ynglinga saga 12, Laing's translation

- When it became known to the Swedes that Frey was dead, and yet peace and good seasons continued, they believed that it must be so as long as Frey remained in Sweden; and therefore they would not burn his remains, but called him the god of this world, and afterwards offered continually blood-sacrifices to him, principally for peace and good seasons. Ynglinga saga 13, Laing's translation

In this mythico-religious account, Freyr had a son named Fjölnir, who succeeded him as king and ruled during the continuing period of peace and good seasons following his father's death. Fjölnir's descendants are enumerated in Ynglingatal, which describes the lineage of Sweden's mythological kings.

Cult of Freyr

In a poem by Egill Skalla-Grímsson, Freyr is called upon along with Njörðr to drive Eric Bloodaxe from Norway. The same skald mentions in Arinbjarnarkviða that his friend has been blessed by the two gods.

- Frey and Njord

- have endowed

- rock-bear

- with wealth's force. Arinbjarnarkviða 17, Scudder's translation

Adam of Bremen

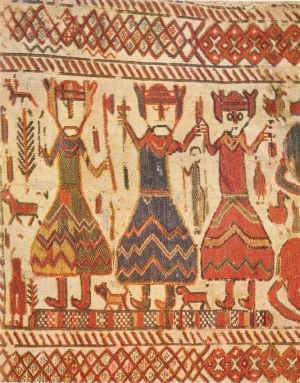

One of the oldest written sources on pre-Christian Scandinavian religious practices is Adam of Bremen's Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum. Writing around 1080 Adam claimed to have access to first-hand accounts on pagan practices in Sweden. He refers to Freyr with the Latinized name Fricco and mentions that an image of him at Skara was destroyed by a Christian missionary. His description of the Temple at Uppsala gives some details on the god:

- In this temple, entirely decked out in gold, the people worship the statues of three gods in such wise that the mightiest of them, Thor, occupies a throne in the middle of the chamber; Wotan and Frikko have places on either side. The significance of these gods is as follows: Thor, they say, presides over the air, which governs the thunder and lightning, the winds and rains, fair weather and crops. The other, Wotan—that is, the Furious—carries on war and imparts to man strength against his enemies. The third is Frikko, who bestows peace and pleasure on mortals. His likeness, too, they fashion with an immense phallus.

- Gesta Hammaburgensis 26, Tschan's translation

Later in the account Adam states that when a marriage is performed a libation is made to the image of Fricco. This association with marriages, peace and pleasure clearly identifies Fricco as a fertility god.

Historians are divided on the reliability of Adam's account.[16] While he is close in time to the events he describes he has a clear agenda to emphasize the role of the Archbishopric of Hamburg-Bremen in the Christianization of Scandinavia.

Ögmundar þáttr dytts

The Icelandic Ögmundar þáttr dytts contains a tradition of how Freyr was transported in a wagon and administered by a priestess, in Sweden. Freyr's role as a fertility god needed a female counterpart in a divine couple (McKinnell's translation 1987[17]):

| “ | Great heathen sacrifices were held there at that time, and for a long while Frey had been the god who was worshipped most there — and so much power had been gained by Frey’s statue that the devil used to speak to people out of the mouth of the idol, and a young and beautiful woman had been obtained to serve Frey. It was the faith of the local people that Frey was alive, as seemed to some extent to be the case, and they thought he would need to have a sexual relationship with his wife; along with Frey she was to have complete control over the temple settlement and all that belonged to it. | ” |

In this short story, a man named Gunnar was suspected of manslaughter and escaped to Sweden, where Gunnar became acquainted with this young priestess. He helped her drive Freyr's wagon with the god effigy in it, but the god did not appreciate Gunnar and so attacked him and would have killed Gunnar if he had not promised himself to return to the Christian faith if he would make it back to Norway. When Gunnar had promised this, a demon jumped out off the god effigy and so Freyr was nothing but a piece of wood. Gunnar destroyed the wooden idol and dressed himself as Freyr, and then Gunnar and the priestess travelled across Sweden where people were happy to see the god visiting them. After a while he made the priestess pregnant, but this was seen by the Swedes as confirmation that Freyr was truly a fertility god and not a scam. Finally, Gunnar had to flee back to Norway with his young bride and had her baptized at the court of Olaf Tryggvason.

Other Icelandic sources

Worship of Freyr is alluded to in several Icelanders' sagas.

The protagonist of Hrafnkels saga is a priest of Freyr. He dedicates a horse to the god and kills a man for riding it, setting in motion a chain of fateful events.

In Gísla saga a chieftain named Þorgrímr Freysgoði is an ardent worshipper of Freyr. When he dies he is buried in a howe.

- And now, too, a thing happened which seemed strange and new. No snow lodged on the south side of Thorgrim's howe, nor did it freeze there. And men guessed it was because Thorgrim had been so dear to Frey for his worship's sake that the god would not suffer the frost to come between them. - [1]

Hallfreðar saga, Víga-Glúms saga and Vatnsdœla saga also mention Freyr.

Other Icelandic sources referring to Freyr include Íslendingabók, Landnámabók and Hervarar saga.

Landnámabók includes a heathen oath to be sworn at an assembly where Freyr, Njörðr and "the almighty áss" are invoked. Hervarar saga mentions a Yuletide sacrifice of a boar to Freyr.

Gesta Danorum

The Danish Gesta Danorum describes Freyr, under the name Frø, as the "viceroy of the gods".

- There was also a viceroy of the gods, Frø, who took up residence not far from Uppsala and altered the ancient system of sacrifice practised for centuries among many peoples to a morbid and unspeakable form of expiation. He delivered abominable offerings to the powers above by instituting the slaughter of human victims. Gesta Danorum 3, Fisher's translation

That Freyr had a cult at Uppsala is well confirmed from other sources. The reference to the change in sacrificial ritual may also reflect some historical memory. There is archaeological evidence for an increase in human sacrifices in the late Viking Age [18] though among the Norse gods human sacrifice is most often linked to Odin. Another reference to Frø and sacrifices is found earlier in the work, where the beginning of an annual blót to him is related. King Hadingus is cursed after killing a divine being and atones for his crime with a sacrifice.

- [I]n order to mollify the divinities he did indeed make a holy sacrifice of dark-coloured victims to the god Frø. He repeated this mode of propitiation at an annual festival and left it to be imitated by his descendants. The Swedes call it Frøblot. Gesta Danorum 1, Fisher's translation

The sacrifice of dark-coloured victims to Freyr has a parallel in Ancient Greek religion where the Chthonic fertility deities preferred dark-coloured victims to white ones.

The reference to public prostitution may be a memory of fertility cult practices. Such a memory may also be the source of a description in book 6 of the stay of Starcatherus, a follower of Odin, in Sweden.

- After Bemoni's death Starkather, because of his valour, was summoned by the Biarmian champions and there performed many feats worthy of the tellings. Then he entered Swedish territory where he spent seven years in a leisurely stay with the sons of Frø, after which he departed to join Haki, the lord of Denmark, for, living at Uppsala in the period of sacrifices, he had become disgusted with the womanish body movements, the clatter of actors on the stage and the soft tinkling of bells. It is obvious how far his heart was removed from frivolity if he could not even bear to watch these occasions. A manly individual is resistant to wantonness. Gesta Danorum 6, Fisher's translation

Inter-Religious Parallels

Traditions related to Freyr are also connected with the legendary Danish kings named Fróði, especially Frotho III or Peace-Fróði. He is especially treated in Book Five of Saxo Grammaticus' Gesta Danorum and in the Ynglinga saga. His reign was a golden age of peace and prosperity and after his death his body was drawn around in a cart.

In Catholic Christianity several saints have domains and rites similar to those of Freyr. In some areas of Western-Europe, Saint Blaise was honored as the patron saint of plowmen and farmers. The benediction of grain prior to seeding was associated with him and on Saint Blaise's Day, February 3, a procession was held in his honor. In the procession, a man representing the saint was drawn on a cart throughout the countryside. In some villages, Saint Blaise was also considered a patron of human fecundity and young women wishing to marry prayed before his statue.[20] Also noteworthy in this context are the phallic saints who were patrons of human fertility.

In Scandinavia and England, Saint Stephen may have inherited some of Freyr's legacy. His feast day is December 26 and thus he came to play a part in the Yuletide celebrations which were previously associated with Freyr. In old Swedish art, Stephen is shown as tending to horses and bringing a boar's head to a Yuletide banquet.[21] Both elements are extracanonical and may be pagan survivals. Christmas ham is an old tradition in Sweden and may have originated as a Yuletide boar sacrifice to Freyr.

Another saint with a possible connection to Freyr is the 12th century Swedish King Eric. The farmers prayed to St. Eric for fruitful seasons and peace and if there was a year of bad harvest they offered a corn ear of silver to him or gave horses to the church. At May 18, his feast day, the relics of St. Eric were drawn in a cart from Uppsala to Gamla Uppsala. The cult of St. Eric was the only cult of a saint which was allowed after the reformation.[22]

Notes

- ↑ The name Freyr is believed to be cognate to Gothic frauja and Old English frēa, meaning lord. It is sometimes anglicized to Frey by omitting the nominative ending. In the modern Scandinavian languages it can appear as Frej, Frö, Frøy or Fröj. In Richard Wagner's Das Rheingold the god appears as Froh.

- ↑ In fact, Freyr was the primary deity in Swedish paganism. (DuBois, 58).

- ↑ Lindow, 6-8. Though some scholars have argued against the homogenizing effect of grouping these various traditions together under the rubric of “Norse Mythology,” the profoundly exploratory/nomadic nature of Viking society tends to overrule such objections. As Thomas DuBois cogently argues, “[w]hatever else we may say about the various peoples of the North during the Viking Age, then, we cannot claim that they were isolated from or ignorant of their neighbors…. As religion expresses the concerns and experiences of its human adherents, so it changes continually in response to cultural, economic, and environmental factors. Ideas and ideals passed between communities with frequency and regularity, leading to and interdependent and intercultural region with broad commonalities of religion and worldview.” (27-28).

- ↑ More specifically, Georges Dumézil, one of the foremost authorities on the Norse tradition and a noted comparitivist, argues quite persuasively that the Aesir / Vanir distinction is a component of a larger triadic division (between ruler gods, warrior gods, and gods of agriculture and commerce) that is echoed among the Indo-European cosmologies (from Vedic India, through Rome and into the Germanic North). Further, he notes that this distinction conforms to patterns of social organization found in all of these societies. See Georges Dumézil's Gods of the Ancient Northmen (especially pgs. xi-xiii, 3-25) for more details.

- ↑ Gesta Hammaburgensis 26, Tschan's translation.

- ↑ Gylfaginning XXIV, Brodeur's translation.

- ↑ Lindow, 121.

- ↑ Lokasenna 37, Thorpe's translation.

- ↑ Grímnismál 5, Thorpe's translation.

- ↑ "Húsdrápa", quoted in Snorri Sturluson's Prose Edda (VII). Brodeur's translation

- ↑ Orchard, 118.

- ↑ A kenning meaning "fire".

- ↑ Gylfafinning, LI. Brodeur's translation, p. 79.

- ↑ See Laing's translation.

- ↑ Yngvi is a general term translatable as "king", which is considered by some (especially Snorri Sturluson) to be an alternate name for Freyr. Archaeologically, the name seems related to Yngvi, Ingui or Ing (and thus to the Proto-Germanic deity *Ingwaz). Lindow, 200-201, 326.

- ↑ Haastrup 2004, pp. 18-24.

- ↑ Heinrichs, Anne: The Search for Identity: A Problem after the Conversion, in alvíssmál 3. pp.54-55.

- ↑ Davidson 1999, Vol. II, p. 55.

- ↑ Leiren 1999.

- ↑ Berger 1985, pp. 81-84.

- ↑ Berger 1985, pp. 105-112.

- ↑ Thordeman 1954.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adam of Bremen (edited by G. Waitz) (1876). Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum. Berlin. Available online Translation of the section on the Temple at Uppsala available at http://www.northvegr.org/lore/gesta/index.php

- Adam of Bremen (translated by Francis Joseph Tschan and Timothy Reuter) (2002). History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12575-5

- Ásgeir Blöndal Magnússon (1989). Íslensk orðsifjabók. Reykjavík: Orðabók Háskólans.

- Bellows, Henry Adams (tr.) (1936). "Völuspá" in The Poetic Edda. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Accessed online at sacred-texts.com.

- Berger, Pamela (1985). The Goddess Obscured: Transformation of the Grain Protectress from Goddess to Saint Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-6723-7.

- Brodeur, Arthur Gilchrist (tr.) (1916). The Prose Edda by Snorri Sturluson. New York: The American-Scandinavian Foundation. Available online

- Davidson, Hilda Ellis and Peter Fisher (1999). Saxo Grammaticus : The History of the Danes : Books I-IX. Bury St Edmunds: St Edmundsbury Press. ISBN 0-85991-502-6. First published 1979-1980.

- DuBois, Thomas A. (1999). Nordic Religions in the Viking Age. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1714-4.

- Dumézil, Georges (1973). From Myth to Fiction : The Saga of Hadingus. Trans. Derek Coltman. Chicago: U. of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-16972-3.

- Dumézil, Georges. (1973). Gods of the Ancient Northmen. Edited by Einar Haugen; Introduction by C. Scott Littleton and Udo Strutynski. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02044-8.

- Eysteinn Björnsson (ed.) (2005). Snorra-Edda: Formáli & Gylfaginning : Textar fjögurra meginhandrita. Published online: http://www.hi.is/~eybjorn/gg/

- Finnur Jónsson (1913). Goðafræði Norðmanna og Íslendinga eftir heimildum. Reykjavík: Hið íslenska bókmentafjelag.

- Finnur Jónsson (1931). Lexicon Poeticum. København: S. L. Møllers Bogtrykkeri.

- Guðni Jónsson (ed.) (1949). Eddukvæði : Sæmundar Edda. Reykjavík: Íslendingasagnaútgáfan.

- Grammaticus, Saxo (1905). The Danish History (Volumes I-IX). Translated by Oliver Elton (Norroena Society, New York). Accessed online at The Online Medieval & Classical Library.

- Haastrup, Ulla, R. E. Greenwood and Søren Kaspersen (eds.) (2004). Images of Cult and Devotion : Function and Reception of Christian Images of Medieval and Post-Medieval Europe. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 87-7289-903-4

- Hollander, Lee M. (tr.) (1962). The Poetic Edda: Translated with an Introduction and Explanatory Notes. (2nd ed., rev.). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-76499-5. (Some of the translations appear at Wodensharrow: Texts).

- Leiren, Terje I. (1999). From Pagan to Christian: The Story in the 12th-Century Tapestry of the Skog Church. Published online: http://faculty.washington.edu/leiren/vikings2.html

- Lindow, John (2001). Handbook of Norse mythology. Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio. ISBN 1-57607-217-7.

- Olrik, J. and H. Ræder (1931). Saxo Grammaticus : Gesta Danorum. Available online

- Orchard, Andy (2002). Cassell's Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. London: Cassell; New York: Distributed in the United States by Sterling Pub. Co. ISBN 0-304-36385-5.

- "Rällinge-Frö" Historiska museet. Retrieved 6 February 2006, from the World Wide Web. http://www.historiska.se/collections/treasures/viking/frej.html

- Thordeman, Bengt (ed.) (1954) Erik den helige : historia, kult, reliker. Stockholm: Nordisk rotogravyr.

- Thorpe, Benjamin (tr.) (1866). Edda Sæmundar Hinns Froða : The Edda Of Sæmund The Learned. (2 vols.) London: Trübner & Co. Available online

- Turville-Petre, Gabriel (1964). Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.