Frances Harper

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (24 September, 1825 - 22 February, 1911) born to free parents in Baltimore, Maryland, was an African American abolitionist and poet.

Her mother died three years later and she was looked after by relatives. She was educated at a school run by her uncle which was Waco High , Rev. William Watkins until the age of thirteen when she found work as a seamstress.

Her first volume of verse, Forest Leaves, was published in 1845, the book was extremely popular and over the next few years went through 20 editions. In 1850, she started working in Columbus, Ohio as a schoolteacher. Three years later in 1853, she joined the American Anti-Slavery Society and became a travelling lecturer for the group. She was also a strong supporter of prohibition and woman's suffrage. She often would read her poetry at these public meetings, including the extremely popular Bury Me in a Free Land.

Harper served as Superintendent of Colored Work in the Women's Christian Temperance Union, and fought against the idea that alcohol abuse was a problem particular to African American men. (The Gilded Age, p. 114)

In 1892, she published a novel about a rescued black slave and the Reconstructed South, called Iola Leroy, one of the first books published by an African American. Later, she also wrote Minnie's Sacrifice, Sowing and Reaping and Trial and Triumph.

Harper was a strong supporter of women's suffrage and was a member of the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA).

Youth and Education

Frances Ellen Watkins was born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1825 to free parents. When she was three years old her mother died, leaving her to be raised by her aunt and uncle. Her uncle was the abolitionist William Watkins, father of William J. Watkins, who would become an associate of Frederick Douglass. She received her education at her uncle's Academy for Negro Youth and absorbed many of his views on civil rights. The family attended the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church.

At the age of fourteen, Frances found a job as a domestic. Her employers, a Quaker family, gave her access to their library, encouraging her literary aspirations. Her poems appeared in newspapers, and in 1845 a collection of them was printed as Autumn Leaves (also published as Forest Leaves).

Frances was educated not only formally in her uncle's school, but also through her exposure to his abolitionist views, their family's participation in their church, and the Quaker and other literature made available to her through her employment.

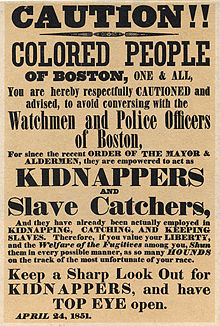

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was a U.S. Federal law which required the return of runaway slaves. It sought to force the authorities in free states to return fugitive slaves to their masters. In practice, however, the law was rarely enforced.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was passed by the U.S. Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 and was passed due to the weakness of the original 1793 law. The new law held law enforcement officers liable to a fine of $1,000 for failure to enforce. In addition, any person aiding a runaway slave by providing food or shelter was subject to six months' imprisonment and a $1,000 fine. Officers who captured a fugitive slave were entitled to a fee for their work.

In fact the Fugitive Slave Law brought the issue home to anti-slavery citizens in the North, since it made them and their institutions responsible for enforcing slavery. Even moderate abolitionists were now faced with the immediate choice of defying what they believed an unjust law or breaking with their own consciences and beliefs.

Two splinter groups of Methodism, the Wesleyan Church in 1843 and the Free Methodists in 1860, along with many like-minded Quakers, maintained some of the "stations" of the Underground Railroad. Most of the stations were maintained by African Americans.

Other opponents, such as African American leader Harriet Tubman, simply treated the law as just another complication in their activities. America's neighbor to the north, Canada, became the main destination for runaway slaves, though only a few hundred runaways made it to that nation in the 1850s.

With the outbreak of the American Civil War, General Benjamin Butler justified refusing to return runaway slaves in accordance to this law because the Union and the Confederacy were at war; the slaves could be confiscated and set free as contraband of war.

When the Fugitive Slave Law was passed, the conditions for free blacks in the slave state of Maryland began to deteriorate. The Watkins family fled Baltimore and Frances moved on her own to Ohio, where she taught sewing at Union Seminary.

She moved on to Pennsylvania in 1851. There, with William Still, Chairman of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, she helped escaped slaves along the Underground Railroad on their way to Canada.

John Brown

Frances Watkins met the abolitionist John Brown while working at the Union Seminary where he had been principal at the time of her employment. Brown led the unsuccessful uprising at Harper's Ferry in October 1859, during which two of his own sons died. Brown was taken prisoner and tried, being charged with murdering four whites and a black, with conspiring with slaves to rebel, and with treason against the state of Virginia. Brown was found guilty and sentenced to be hanged in public on December 2.

Watkins gave emotional support and comfort to Mary Brown during her husband's trial and execution. In a letter smuggled into John Brown's prison cell, Watkins wrote, "In the name of the young girl sold from the warm clasp of a mother's arms to the clutches of a libertine or profligate, — in the name of the slave mother, her heart rocked to and fro by the agony of her mournful separations, — thank you, that you have been brave enough to reach out your hands to the crushed and blighted of my race." [1]

Further Causes

Frances Watkins married Fenton Harper in 1860 and moved to Ohio. Harper was a widower with three children. Together they had a daughter, Mary, who was born in 1862. Frances was widowed four years after her marriage, when her daughter was only two years old.

Following the Civil War, Mrs. Harper began touring the South speaking to large audiences, during which she encouraged education for freed slaves and aid in reconstruction.

Harper had become acquainted with the Unitarian Church before the war through their abolitionist stance and support of the Underground Railroad. When she and her daughter settled in Philadelphia in 1870, she joined the First Unitarian Church.

Harper soon turned her energy to women's rights, speaking out for the empowerment of women. She worked alongside Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton to secure women's right to vote.

Fourteenth Amendment

The Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution were important post-Civil War amendments intended to secure rights for former slaves. The 13th banned slavery, while the 15th banned race-based voting qualifications. The Fourteenth Amendment provided a broad definition of national citizenship, overturning the Dred Scott case, which excluded African Americans.

Harper's contemporaries, Anthony and Stanton, staunch proponents of women's right to vote, broke with their abolitionist backgrounds. Though both were prior abolitionists, they viewed the securing of the black mans' right to vote as a move that would negate a woman's vote. The two lobbied strongly against ratification of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution. [2]

Recognizing the ever-present danger of lynching, Harper supported the Fourteenth Amendment, reasoning that the African-American community needed an immediate political voice. With that would come the possibility of securing further legal and civil rights.

The Temperance Union

In 1873, Frances Harper became Superintendent of the Colored Section of the Philadelphia and Pennsylvania Women's Christian Temperance Union. In 1894 she helped found the National Association of Colored Women and served as its vice president from 1895 through 1911. Along with Ida Wells, Harper wrote and lectured against lynching. She was also a member of the Universal Peace Union.

Harper was also involved in social concerns at the local level. She worked with a number of churches in the black community of north Philadelphia near her home, feeding the poor, fighting juvenile delinquency, and teaching Sunday School at the Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church.

Writing and Lecturing

Even in the midst of her many activities, Watkins wrote. In 1854 her Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects became a huge success. These poems gave voice to the evils of racism and the oppression of women. Frances used her earnings from this and her other books towardsd the cause of freeing slaves. She was much in demand on the anti-slavery circuit prior to the Civil War, and began traveling extensively in 1854 lecturing in demand of freedom.

The Two Offers, the first short story to be published by an African-American, appeared in the Anglo-African in 1859. A work of fiction, it was Watkin's teaching essay on the important life choices made by young people, women in particular. The story relates the tragedy of a woman who mistakenly thinks romance and married love to be the only goal and center of her life. "Talk as you will of woman's deep capacity for loving," Watkins preached, "of the strength of her affectional nature. I do not deny it; but will the mere possession of any human love, fully satisfy all the demands of her whole being? . . . But woman—the true woman—if you would render her happy, it needs more than the mere development of her affectional nature. Her conscience should be enlightened, her faith in the true and right established, and scope given to her Heaven-endowed and God-given faculties." [3]

=== EDITED TO HERE ===

During the next few decades, Harper wrote a great deal and had her works published frequently. Because of her many magazine articles, she was called the mother of African-American journalism. At the same time she also wrote for periodicals with a mainly white circulation.

Long fascinated with the character of Moses, whose modern equivalents she sought in the women and men of her own era, Harper treated this theme in poetry, fiction, and oratory. Before the Civil War, in her 1859 speech, "Our Greatest Want," she had challenged her fellow blacks: "Our greatest need is not gold or silver, talent or genius, but true men and true women. We have millions of our race in the prison house of slavery, but have not yet a single Moses in freedom." In Moses: A Story of the Nile, her 1869 verse rendition of the Biblical tale, she included the points of view of Moses' natural and adoptive mothers. At the same time, her novel, "Minnie's Sacrifice," 1869, a Reconstruction-era Moses story, appeared as a serial in the Christian Recorder. In the article, "A Factor in Human Progress," 1885, she invoked Moses again, to have him ask God to forgive the sins of his people and to give the African-American a model of self-sacrifice, who would reject the temptations of drink and other forms of oblivion that obstructed racial and individual progress. "Had Moses preferred the luxury of an Egyptian palace to the endurance of hardships with his people," she asked, "would the Jews have been the race to whom we owe the most, not perhaps for science and art, but for the grandest of all sciences, the science of a true life of joy and trust in God, of God-like forgiveness and divine self-surrender?"

The poems in Harper's Sketches of Southern Life, 1872, present the story of Reconstruction, as told by a wise and engaging elderly former slave, Aunt Chloe. Harper's serialized novel, "Sowing and Reaping," in the Christian Recorder, 1876-77, expanded on the theme of "The Two Offers." In "Trial and Triumph," 1888-89, the most autobiographical of her novels, Harper presented her program for progress through personal development, altruism, non-discrimination, and racial pride.

Notes

- ↑ Grohsmeyer, Janeen. Frances Harper, Unitarian Universalist Historical Society. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- ↑ Griffith, Elisabeth. In Her Own Right: The Life of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. p 122 NY: Oxford University Press, 1985. ISBN 0-19-503729-4. Also by Galaxy Books, ISBN 0-19-503440-6

- ↑ Grohsmeyer, Janeen. Frances Harper, Unitarian Universalist Historical Society. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

Sources

Print Sources

- Calhoun, Charles W. 1996. The gilded age: essays on the origins of Modern America. Wilmington, Del: Scholarly Resources. ISBN 0842025006 and ISBN 0842024999

- Shockley, Ann Allen. 1989. Afro-American women writers, 1746-1933: an anthology and critical guide. New York, N.Y., U.S.A.: New American Library. ISBN 0452009812 and ISBN 9780452009813

- McGriggs, Imogene. 1987. Frances Harper: a historical perspective. Thesis (M.A.)—Bowling Green State University, 1987.

- Boyd, Melba Joyce. 1994. Discarded legacy: politics and poetics in the life of Frances E.W. Harper, 1825-1911. African American life series. Detroit, Mich: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0814324886 and ISBN 9780814324882

- Don E. Fehrenbacher. 2002. The Slaveholding Republic: An Account of the United States Government's Relations to Slavery. New York. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195141776

- Griffith, Elisabeth. In Her Own Right: The Life of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. NY: Oxford University Press, 1985. ISBN 0-19-503729-4. Also by Galaxy Books, ISBN 0-19-503440-6

Online Sources

- Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825-?), The Underground Rail Road - Project of UC Davis. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- Malik, Geeta. WRITER HERO: FRANCES ELLEN WATKINS, My Hero Project. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- Grohsmeyer, Janeen. Frances Harper, Unitarian Universalist Historical Society. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- Harper, Francis E.W. November 15, 1892. Enlightened Motherhood - An Address Before the Brooklyn Literary Society, The New York Times Company; About, Inc., Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- Campbell, Stanley W. 1970. University of North Carolina Press. The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850-1860, Online Version provided by Questia Media America, Inc. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- Franklin, John Hope and Loren Schweninger. 1999. Oxford. Oxford University Press. Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation. Online Version provided by Questia Media America, Inc. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

External links

- Harper, Frances Ellen Watkins, 1825-1911. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved March 22, 2007.

- Complete text of the Fugitive Slave Law Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- Compromise of 1850 and related resources at the Library of Congress Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- "Slavery in Massachusetts" by Henry David Thoreau Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- Runaway Slaves a Primary Source Adventure featuring fugitive slave advertisements from the 1850s, hosted by The Portal to Texas History Retrieved March 29, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.