Frankfurter, Felix

Laura Brooks (talk | contribs) (import, credit, version number) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (14 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Copyedited}}{{approved}}{{images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}} | ||

| + | {{epname|Frankfurter, Felix}} | ||

{{Infobox Judge | {{Infobox Judge | ||

| − | | name | + | | name = Felix Frankfurter |

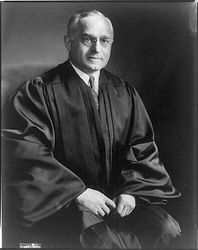

| − | | image | + | | image = Frankfurter-Felix-LOC.jpg |

| − | | imagesize | + | | imagesize = |

| − | | caption | + | | caption = |

| − | | office | + | | office = [[Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States|Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court]] |

| − | | termstart | + | | termstart = January 30, 1939 |

| − | | termend | + | | termend = August 28, 1962 |

| − | | nominator | + | | nominator = [[Franklin Delano Roosevelt]] |

| − | | appointer | + | | appointer = |

| − | | predecessor | + | | predecessor = [[Benjamin N. Cardozo]] |

| − | | successor | + | | successor = [[Arthur Goldberg]] |

| − | | office2 | + | | office2 = |

| − | | termstart2 | + | | termstart2 = |

| − | | termend2 | + | | termend2 = |

| − | | nominator2 | + | | nominator2 = |

| − | | appointer2 | + | | appointer2 = |

| − | | predecessor2 | + | | predecessor2 = |

| − | | successor2 | + | | successor2 = |

| − | | birthdate | + | | birthdate = {{birth date|1882|11|15|mf=y}} |

| − | | birthplace | + | | birthplace = [[Vienna]], [[Austria]] |

| − | | deathdate | + | | deathdate = {{death date and age|1965|2|22|1882|11|15|mf=y}} |

| − | | deathplace | + | | deathplace = [[Washington, D.C.]] |

| − | | spouse | + | | spouse = |

}} | }} | ||

| − | '''Felix Frankfurter''' ( | + | '''Felix Frankfurter''' (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an [[Associate Justice]] of the [[Supreme Court of the United States|United States Supreme Court]]. He was known as the nation's preeminent scholar on labor law. From 1914 to his appointment to the Supreme Court, Frankfurter was a popular [[professor]] at [[Harvard Law School]]. He helped found the [[American Civil Liberties Union]] and served as an informal advisor to President [[Franklin Delano Roosevelt]] on many [[New Deal]] measures. |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

==Early life== | ==Early life== | ||

| − | Frankfurter was born in [[Vienna, Austria]]. | + | Frankfurter was born in [[Vienna, Austria]]. His family emigrated to the [[United States]] when he was twelve years old in 1894. They lived in New York City's [[Lower East Side]]. After graduating from [[City College of New York]], he enrolled in [[New York Law School]], but in 1902 transferred to [[Harvard Law School]], where he became an editor of the ''[[Harvard Law Review]]'' and eventually graduated with one of the best academic records since [[Louis Brandeis]]. |

==Legal career== | ==Legal career== | ||

| − | In | + | In 1906, Frankfurter became the assistant of [[Henry Stimson]], a New York attorney. In 1911, [[William Howard Taft|President Taft]] appointed Stimson as his [[United States Secretary of War|Secretary of War]] and Stimson appointed Frankfurter as law officer of the [[Bureau of Insular Affairs]]. During the [[World War I|War in Europe]] he acted as major and judge-advocate, and as secretary and counsel of the President's mediation commission. |

| − | In | + | In 1918, leaders within the American Jewish community convened the first [[American Jewish Congress]] in [[Philadelphia]]'s historic [[Independence Hall (United States)|Independence Hall]]. Frankfurter, joined by [[Rabbi Stephen Wise]], U.S. Supreme Court Justice [[Louis Brandeis]], and others to lay the groundwork for a national Democratic organization comprised of Jewish leaders from all over the country, to rally for equal rights for all Americans regardless of race, religion or national ancestry. |

| − | In | + | In 1919, Frankfurter served as a [[Zionism|Zionist]] delegate to the [[Paris Peace Conference, 1919|Paris Peace Conference]]. He lobbied President [[Woodrow Wilson]] to incorporate the [[Balfour Declaration of 1917|Balfour Declaration]] into the treaty. In 1920, Frankfurter helped to found the [[American Civil Liberties Union]]. In the late 1920s, he joined efforts to save the lives of [[Nicola Sacco]] and [[Bartolomeo Vanzetti]], two [[anarchist]]s who had been sentenced to death on robbery and murder charges. |

==Criminal justice in Cleveland== | ==Criminal justice in Cleveland== | ||

| − | In | + | In 1922, [[Roscoe Pound]] and Felix Frankfurter undertook a detailed quantitative study of crime reporting in [[Cleveland, Ohio|Cleveland]], [[Ohio]], [[newspaper]]s for January 1919, counting column inches. They found that whereas, in the first half of the month, the total amount of space given over to crime was 925 inches, in the second half it leapt to 6,642 inches. This was in spite the fact that the number of crimes reported had increased only from 345 to 363. |

| − | They concluded that although the city's much publicized "[[crime wave]]" was largely fictitious and manufactured by the press, the coverage had a very real consequence for the administration of criminal justice. | + | They concluded that although the city's much publicized "[[crime wave]]" was largely fictitious and manufactured by the press, the coverage had a very real consequence for the administration of criminal justice. Because the public believed they were in the middle of a crime epidemic, they demanded an immediate response from the police and the city authorities. These agencies complied, wishing to retain public support, caring "more to satisfy popular demand than to be observant of the tried process of law." The result was a greatly increased likelihood of miscarriages of justice and sentences more severe than the offenses warranted.<ref> Jensen, Klaus Bruhn. ''A Handbook of Media and Communication Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Methodologies''. London: Routledge 2002. ISBN 9780415225885 </ref><ref> Cleveland Foundation, Roscoe Pound, Felix Frankfurter, and Raymond B. Fosdick. ''Criminal justice in Cleveland; reports of the Cleveland Foundation survey of the administration of criminal justice in Cleveland, Ohio''. Montclair, N.J.: Patterson Smith 1968. OCLC 451741 </ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

His long research into the power behind government in the United States led him to state "The real rulers in [[Washington, D.C.|Washington]] are invisible, and exercise power from behind the scenes." | His long research into the power behind government in the United States led him to state "The real rulers in [[Washington, D.C.|Washington]] are invisible, and exercise power from behind the scenes." | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Supreme Court== | ==Supreme Court== | ||

| − | On | + | On January 5, 1939, President [[Franklin Delano Roosevelt]] nominated Frankfurter to the [[United States Supreme Court|U.S. Supreme Court]]. He served from January 30, 1939, to August 28, 1962. |

| − | Despite his [[ | + | Despite his [[American liberalism|liberal]] political leanings, Frankfurter became the court's most outspoken advocate of [[judicial restraint]], the view that courts should not interpret the fundamental law, the [[constitution]], in such a way as to impose sharp limits upon the authority of the [[legislature|legislative]] and [[executive (government)|executive]] branches. In this philosophy, Frankfurter was heavily influenced by his close friend and mentor [[Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.]], who had taken a firm stand during his tenure on the bench against the doctrine of "economic [[due process]]." Frankfurter revered Justice Holmes, often citing Holmes in his opinions. In practice this meant Frankfurter was generally willing to uphold the actions of those branches against constitutional challenges so long as they did not "shock the conscience." Frankfurter was particularly well known as a scholar of [[civil procedure]]. Later in his career, this philosophy frequently put him on the dissenting side of ground-breaking decisions of the [[Earl Warren|Warren]] court. However, Frankfurter was a strong foe of [[racial segregation]] and joined the Court's unanimous opinion in ''[[Brown v. Board of Education]]'' (1954), which prohibited segregation in [[public school]]s. Frankfurter encouraged the [[Morgenthau Plan]] against Germany in [[World War II]]. |

| − | + | Frankfurter retired in 1962 after suffering a [[stroke]] and was succeeded by [[Arthur Goldberg]]. He was awarded the [[Presidential Medal of Freedom]] in 1963. | |

| − | Frankfurter retired in | ||

Felix Frankfurter died from [[congestive heart failure]] at the age of 83. His remains are interred in the [[Mount Auburn Cemetery]] in [[Cambridge, Massachusetts|Cambridge]], [[Massachusetts]]. | Felix Frankfurter died from [[congestive heart failure]] at the age of 83. His remains are interred in the [[Mount Auburn Cemetery]] in [[Cambridge, Massachusetts|Cambridge]], [[Massachusetts]]. | ||

| − | There are two extensive collections of Frankfurter's papers: one at the Manuscript Division of the [[Library of Congress]] and the other at Harvard University. | + | ==Legacy== |

| + | There are two extensive collections of Frankfurter's papers: one at the Manuscript Division of the [[Library of Congress]] and the other at Harvard University. Both are fully open for research and have been distributed to other libraries on microfilm. A chapter of the [[Aleph Zadik Aleph]] is named in his honor. | ||

| − | + | Frankfurter published several books including ''Cases Under the Interstate Commerce Act;'' ''The Business of the Supreme Court'' (1927); ''Justice Holmes and the Supreme Court'' (1938); ''The Case of Sacco and Vanzetti'' (1927) and ''Felix Frankfurter Reminisces'' (1960). | |

| − | Frankfurter | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | < | + | <references/> |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ==References== | |

| + | * Hirsch, H. N. ''The enigma of Felix Frankfurter''. New York: Basic Books, 1981. ISBN 978-0465019793 | ||

| + | * Parrish, Michael E. ''Felix Frankfurter and his times''. New York: Free Press, 1982. ISBN 978-0029237403 | ||

| + | * Walker, Samuel. ''In defense of American liberties: a history of the ACLU''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0195045390 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved March 25, 2024. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | *[http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=363 Felix Frankfurter's Gravesite] | |

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * [http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=363 Felix Frankfurter's Gravesite] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{start box}} | {{start box}} | ||

| − | {{succession box|title=[[List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States|Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States]]|before=[[Benjamin N. Cardozo]]|after=[[Arthur Goldberg]]|years= | + | {{succession box|title=[[List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States|Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States]]|before=[[Benjamin N. Cardozo]]|after=[[Arthur Goldberg]]|years=January 30, 1939–August 28, 1962}} |

{{end box}} | {{end box}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:History]] | [[Category:History]] | ||

[[Category:Biography]] | [[Category:Biography]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:13, 26 March 2024

| Felix Frankfurter | |

| |

Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court

| |

| In office January 30, 1939 – August 28, 1962 | |

| Nominated by | Franklin Delano Roosevelt |

|---|---|

| Preceded by | Benjamin N. Cardozo |

| Succeeded by | Arthur Goldberg |

| Born | November 15 1882 Vienna, Austria |

| Died | February 22 1965 (aged 82) Washington, D.C. |

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. He was known as the nation's preeminent scholar on labor law. From 1914 to his appointment to the Supreme Court, Frankfurter was a popular professor at Harvard Law School. He helped found the American Civil Liberties Union and served as an informal advisor to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt on many New Deal measures.

Early life

Frankfurter was born in Vienna, Austria. His family emigrated to the United States when he was twelve years old in 1894. They lived in New York City's Lower East Side. After graduating from City College of New York, he enrolled in New York Law School, but in 1902 transferred to Harvard Law School, where he became an editor of the Harvard Law Review and eventually graduated with one of the best academic records since Louis Brandeis.

Legal career

In 1906, Frankfurter became the assistant of Henry Stimson, a New York attorney. In 1911, President Taft appointed Stimson as his Secretary of War and Stimson appointed Frankfurter as law officer of the Bureau of Insular Affairs. During the War in Europe he acted as major and judge-advocate, and as secretary and counsel of the President's mediation commission.

In 1918, leaders within the American Jewish community convened the first American Jewish Congress in Philadelphia's historic Independence Hall. Frankfurter, joined by Rabbi Stephen Wise, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, and others to lay the groundwork for a national Democratic organization comprised of Jewish leaders from all over the country, to rally for equal rights for all Americans regardless of race, religion or national ancestry.

In 1919, Frankfurter served as a Zionist delegate to the Paris Peace Conference. He lobbied President Woodrow Wilson to incorporate the Balfour Declaration into the treaty. In 1920, Frankfurter helped to found the American Civil Liberties Union. In the late 1920s, he joined efforts to save the lives of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, two anarchists who had been sentenced to death on robbery and murder charges.

Criminal justice in Cleveland

In 1922, Roscoe Pound and Felix Frankfurter undertook a detailed quantitative study of crime reporting in Cleveland, Ohio, newspapers for January 1919, counting column inches. They found that whereas, in the first half of the month, the total amount of space given over to crime was 925 inches, in the second half it leapt to 6,642 inches. This was in spite the fact that the number of crimes reported had increased only from 345 to 363.

They concluded that although the city's much publicized "crime wave" was largely fictitious and manufactured by the press, the coverage had a very real consequence for the administration of criminal justice. Because the public believed they were in the middle of a crime epidemic, they demanded an immediate response from the police and the city authorities. These agencies complied, wishing to retain public support, caring "more to satisfy popular demand than to be observant of the tried process of law." The result was a greatly increased likelihood of miscarriages of justice and sentences more severe than the offenses warranted.[1][2] His long research into the power behind government in the United States led him to state "The real rulers in Washington are invisible, and exercise power from behind the scenes."

Supreme Court

On January 5, 1939, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt nominated Frankfurter to the U.S. Supreme Court. He served from January 30, 1939, to August 28, 1962.

Despite his liberal political leanings, Frankfurter became the court's most outspoken advocate of judicial restraint, the view that courts should not interpret the fundamental law, the constitution, in such a way as to impose sharp limits upon the authority of the legislative and executive branches. In this philosophy, Frankfurter was heavily influenced by his close friend and mentor Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., who had taken a firm stand during his tenure on the bench against the doctrine of "economic due process." Frankfurter revered Justice Holmes, often citing Holmes in his opinions. In practice this meant Frankfurter was generally willing to uphold the actions of those branches against constitutional challenges so long as they did not "shock the conscience." Frankfurter was particularly well known as a scholar of civil procedure. Later in his career, this philosophy frequently put him on the dissenting side of ground-breaking decisions of the Warren court. However, Frankfurter was a strong foe of racial segregation and joined the Court's unanimous opinion in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which prohibited segregation in public schools. Frankfurter encouraged the Morgenthau Plan against Germany in World War II.

Frankfurter retired in 1962 after suffering a stroke and was succeeded by Arthur Goldberg. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1963.

Felix Frankfurter died from congestive heart failure at the age of 83. His remains are interred in the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Legacy

There are two extensive collections of Frankfurter's papers: one at the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress and the other at Harvard University. Both are fully open for research and have been distributed to other libraries on microfilm. A chapter of the Aleph Zadik Aleph is named in his honor.

Frankfurter published several books including Cases Under the Interstate Commerce Act; The Business of the Supreme Court (1927); Justice Holmes and the Supreme Court (1938); The Case of Sacco and Vanzetti (1927) and Felix Frankfurter Reminisces (1960).

Notes

- ↑ Jensen, Klaus Bruhn. A Handbook of Media and Communication Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Methodologies. London: Routledge 2002. ISBN 9780415225885

- ↑ Cleveland Foundation, Roscoe Pound, Felix Frankfurter, and Raymond B. Fosdick. Criminal justice in Cleveland; reports of the Cleveland Foundation survey of the administration of criminal justice in Cleveland, Ohio. Montclair, N.J.: Patterson Smith 1968. OCLC 451741

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hirsch, H. N. The enigma of Felix Frankfurter. New York: Basic Books, 1981. ISBN 978-0465019793

- Parrish, Michael E. Felix Frankfurter and his times. New York: Free Press, 1982. ISBN 978-0029237403

- Walker, Samuel. In defense of American liberties: a history of the ACLU. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0195045390

External links

All links retrieved March 25, 2024.

| Preceded by: Benjamin N. Cardozo |

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States January 30, 1939–August 28, 1962 |

Succeeded by: Arthur Goldberg |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.