Difference between revisions of "Farid ad-Din Attar" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Attar statue-1.jpg|thumb|`Attar's statue beside his mausoleum, [[Nishapur]], [[Iran]]]] | |

| − | + | '''Abū Hamīd bin Abū Bakr Ibrāhīm''' (1120- in [[Nishapur]] – died c. 1229), much better known by his pen-names '''Farīd ud-Dīn''' ({{PerB|فریدالدین}}) and '''‘Attār''' ({{PerB|عطار}} - ''"the pharmacist"''), was a [[Persia|Persian]] and [[Muslim]] [[poetry|poet, [[Sufi]], theoretician of mysticism, and [[hagiographer]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | | | ||

| − | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | '''Abū Hamīd bin Abū Bakr Ibrāhīm''' ( | ||

==Biography== | ==Biography== | ||

| − | Information about `Attar's life is rare. He is mentioned by only two of his contemporaries, `Awfi and Khadja Nasir ud-Din Tusi. However, all sources confirm that he was from [[Nishapur]], a major city of medieval [[Greater Khorasan|Khorasan]] (now located in the northeast of [[Iran]]), and according to `Awfi, he was a poet of the [[Great Seljuq Empire|Seljuq period]]. It seems that he was not well known as a poet in his own lifetime, except at his home town, and his greatness as a mystic, a poet, and a master of narrative was not discovered until the 15th century. | + | Information about `Attar's life is rare. He is mentioned by only two of his contemporaries, `Awfi and Khadja Nasir ud-Din Tusi. However, all sources confirm that he was from [[Nishapur]], a major city of medieval [[Greater Khorasan|Khorasan]] (now located in the northeast of [[Iran]]), and according to `Awfi, he was a poet of the [[Great Seljuq Empire|Seljuq period]]. Darbandi and Davis cite 1120 as his possible birth date, commenting that sources indicate a date between 1120 and 1157.<ref>Darbandi and Davis, page 9.</ref> It seems that he was not well known as a poet in his own lifetime, except at his home town, and his greatness as a mystic, a poet, and a master of narrative was not discovered until the 15th century. |

===Life=== | ===Life=== | ||

[[Image:Attar_mausoleum0.jpg|thumb|`Attar's mausoleum in [[Nishapur]], [[Iran]]]] | [[Image:Attar_mausoleum0.jpg|thumb|`Attar's mausoleum in [[Nishapur]], [[Iran]]]] | ||

| − | `Attar was probably the son of a prosperous chemist, receiving an excellent education in various fields. While his works say little else about his life, they tell us that he practiced the profession of pharmacy and personally attended to a very large number of customers. | + | `Attar was probably the son of a prosperous chemist, receiving an excellent [[education]] in various fields. He is said to have attended "the theological school attached to the shrine of Imam Reza at Mashhad."<ref>Darbandi and Davis, page 9.</ref> While his works say little else about his life, they tell us that he practiced the profession of pharmacy and personally attended to a very large number of customers. The people he helped in the pharmacy used to confide their troubles in `Attar, which affected him deeply. Eventually, he abandoned his pharmacy store and traveled widely - to [[Kufa]], [[Mecca]], [[Damascus]], [[Turkistan]], and [[India]], meeting with Sufi [[Shaykh]]s - then returned, promoting Sufi ideas. Such travel in search of [[knowledge]] was not uncommon for Sufi practitioners at the time. |

| − | `Attar | + | On the one hand, `Attar is renowned as a Sufi thinker and writer, on the other hand his exact relationship with any Sufi teacher or order is vague. It is not known for certain which Sufi master instructed him. Possibly, his teacher was Majd ad-Din al-Baghdadi (d. 1219) although Baghdadi may have taught him [[medicine]] not [[theology]]. A tradition "first mentioned by [[Rumi]] has it that he "had no teacher and was instructed in the Way by the spirit of [[Mansur al-Hallaj]], the Sufi [[martyr]] who had been executed in Baghdad in 922 and who appeared to him in a dream." Or, he may have joined a Sufi order then received a "confirmatory dream in which Hallaj appeared to him." Darbandi and Davis suggest that reference to the spirit of Hallaj may be a "dramaticv symbol of his scholarly pre-occupation with the lives of dead saints."<ref>Darbandi and Davis, page 12.</ref> |

| − | + | It can, though, be taken for granted that from childhood onward `Attar, encouraged by his father, was interested in the Sufis and their sayings and way of life, and regarded their saints as his spiritual guides. `Attar "boasted that he had never sought a king's favour or stooped to writing a panegyric" which "alone would make him worthy of note among Persian poets."<ref>Darbandi and Davis, pages 9-10.</ref> `Attar probably supported himself from his work as a chemist or physician. `Attar means [[herbalist]], [[medication|druggist]] and [[perfume|perfumist]], and during his lifetime in [[Persian Empire|Persia]], much of [[medicine]] and drugs were based on [[herb]]s. He says that he "composed his poems in his ''daru-khane''" which means "a chemist's shop or drug-store, but which has suggestions of a dispensary or even a doctor's surgery." It is probable that he "combined the selling of drugs and perfumes with the practice of medicine."<ref>Drabandi and Davis, page 9.</ref> | |

| − | `Attar reached an age of over 70 and died a violent death in the massacre which the [[Mongol Empire|Mongols inflicted on Nishabur]] in April | + | ===Death=== |

| + | `Attar reached an age of over 70 (some sources mention 110) and died a violent death in the massacre which the [[Mongol Empire|Mongols inflicted on Nishabur]] in April 1229 although possible death dates range from 1193 to 1235.<ref>Darbandi and Davis, page 10.</ref> His [[mausoleum]], built by [[Ali-Shir Nava'i]] in the 16th century, is located in Nishapur. | ||

Like many aspects of his life, his death, too, is blended with legends and speculation. A well-known story regarding his death goes as follows: | Like many aspects of his life, his death, too, is blended with legends and speculation. A well-known story regarding his death goes as follows: | ||

| − | + | <blockquote>During the invasion of Persia by [[Ghenghis Khan|Jenghis Khan]] (1229 C.E.) when `Attar had reached the age of 110, he was taken prisoner by the Mongols. One of them was about to kill him, when another said "let the old man live; I will give a thousand pieces of silver as his ransom. His captor was about to close with the bargain, but `Attar said, "Don't sell me as chaeaply; you will find someone willing to give more." Subsequently, another man came up and offered a bag of straw for him. "Sell me to him," said `Attar, for that is all I am worth." The Mongol, irritated at teh loss of the first offer, slew him, who thus found the death he desired.<ref>Field, pages 139-140.</ref> | |

| − | |||

==Teachings== | ==Teachings== | ||

| − | The thought-world depicted in `Attar's works reflects the whole evolution of the Sufi movement. The starting point is the idea that the body-bound soul's awaited release and return to its source in the other world can be experienced during the present life in mystic union attainable through inward purification. | + | The thought-world depicted in `Attar's works reflects the whole evolution of the Sufi movement. The starting point is the idea that the body-bound soul's awaited release and return to its source in the other world can be experienced during the present life in mystic union attainable through inward purification. By explaining his thoughts, the material uses is not only from specifically Sufi but also from older ascetic legacies. Although his heroes are for the most part Sufis and ascetics, he also introduces stories from historical chronicles, collections of anecdotes, and all types of high-esteemed literature. His talent for perception of deeper meanings behind outward appearances enables him to turn details of everyday life into illustrations of his thoughts. The [[idiosyncrasy]] of `Attar's presentations invalidates his works as sources for study of the historical persons whom he introduces. As sources on the [[hagiology]] and [[phenomenology]] of Sufism, however, his works have immense value. |

| − | Judging from `Attar's writings, he viewed | + | Judging from `Attar's writings, he viewed [[philosophy]] with skepticism and dislike. He wrote, "No one is farther from the Arabian prophet than the philosopher. Know that philosophy ''(falsafa)'' is the wont and way of [[Zoroaster]], for philosophy is to turn your back on all religious [[law]]."<ref>Lewisohn, page xx citing from `Attar's ''Book of Adversity''.</ref> Interestingly, he did not want to uncover the secrets of [[nature]]. This is particularly remarkable in the case of medicine, which fell within the scope of his profession. He obviously had no motive for showing off his secular knowledge in the manner customary among court [[panegyrist]]s, whose type of poetry he despised and never practiced. Such knowledge is only brought into his works in contexts where the theme of a story touches on a branch of natural science. |

==Poetry== | ==Poetry== | ||

| − | `Attar speaks of his own poetry in various contexts including the epilogues of his long narrative poems. He confirms the guess likely to be made by every reader that he possessed an inexhaustible fund of thematic and verbal inspiration. He writes that when he composed his poems, more ideas came into his mind than he could possibly use. | + | `Attar speaks of his own poetry in various contexts including the epilogues of his long narrative poems. He confirms the guess likely to be made by every reader that he possessed an inexhaustible fund of thematic and verbal inspiration. He writes that when he composed his poems, more ideas came into his mind than he could possibly use. |

| − | Like his contemporary [[Khaqani]], `Attar was not only convinced that his poetry had far surpassed all previous poetry, but that it was to be intrinsically unsurpassable at any time in the future, seeing himself as the “seal of the poets” and his poetry as the “seal of speech.”<ref> | + | Like his contemporary [[Khaqani]], `Attar was not only convinced that his poetry had far surpassed all previous poetry, but that it was to be intrinsically unsurpassable at any time in the future, seeing himself as the “seal of the poets” and his poetry as the “seal of speech.”<ref>Lewisohn, page 334.</ref> |

==Works== | ==Works== | ||

[[Image:HellmutRitter statue.jpg|thumb|Statue of the German orientalist Hellmut Ritter beside `Attar's mausoleum. It was made by order of [[Goethe]] and [[Hafez]] fans in [[Germany]].]] | [[Image:HellmutRitter statue.jpg|thumb|Statue of the German orientalist Hellmut Ritter beside `Attar's mausoleum. It was made by order of [[Goethe]] and [[Hafez]] fans in [[Germany]].]] | ||

| − | The question whether all the works that have been ascribed to him are really from his pen, has not been solved. This is due to two facts that have been observed in his works: | + | The question whether all the works that have been ascribed to him are really from his pen, has not been solved. This is due to two facts that have been observed in his works: |

# There are considerable differences of style among these works. | # There are considerable differences of style among these works. | ||

| Line 65: | Line 43: | ||

# Works in which [[mysticism]] is in perfect balance with a finished, story-teller's art. | # Works in which [[mysticism]] is in perfect balance with a finished, story-teller's art. | ||

# Works in which a pantheistic zeal gains the upper hand over literary interest. | # Works in which a pantheistic zeal gains the upper hand over literary interest. | ||

| − | # Works in which the aging poet idolizes [[Imam]] [[Ali ibn Abu Talib]] while there is no trace of ordered thoughts and descriptive skills. | + | # Works in which the aging poet idolizes [[Imam]] [[Ali ibn Abu Talib]] while there is no trace of ordered thoughts and descriptive skills. |

| − | + | Phrase three may be coincidental with a conversion to [[Shia|Shi'ism]].<ref>Rittner, </ref> However, in 1941, the Persian scholar Nafisi was able to prove that the works of the third phase in Ritter's classification were written by another `Attar who lived about two hundred and fifty years later at [[Mashhad]] and was a native of Tun. Ritter accepted this finding in the main, but doubted whether Nafisi was right in attributing the works of the second group also to this `Attar of Tun. One of Ritter's arguments is that the principal figure in the second group is not Ali, as in the third group, but [[al-Hallaj|Hallaj]], and that there is nothing in the explicit content of the second group to indicate a Shia allegiance of the author. Another is the important chronological point that a manuscript of the ''Jawhar al-Dāt'', the chief work in the second group, bears the date 735 A.H. (= 1334-35 C.E.). While `Attar of Tun's authorship of the second group is untenable, Nafisi was certainly right in concluding that the style difference (already observed by Ritter) between the works in the first group and those in the second group is too great to be explained by a spiritual evolution of the author. The authorship of the second group remains an unsolved problem.<ref name="Iranica" /> | |

In the introductions of ''Mo<u>kh</u>tār-Nāma'' and ''<u>Kh</u>osrow-Nāma'', `Attar lists the titles of further products of his pen: | In the introductions of ''Mo<u>kh</u>tār-Nāma'' and ''<u>Kh</u>osrow-Nāma'', `Attar lists the titles of further products of his pen: | ||

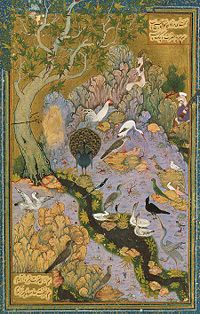

| − | [[Image: conference of the birds.jpg|thumb|right||200px|''“Manteq al-Ṭayr”'' | + | [[Image: conference of the birds.jpg|thumb|right||200px|''“Manteq al-Ṭayr”'' ''(“Conference of the Birds”)'']] |

* ''Dīvān'' | * ''Dīvān'' | ||

* ''Asrār-Nāma'' | * ''Asrār-Nāma'' | ||

| Line 86: | Line 64: | ||

*Asrar Nameh (Book of Secrets) about Sufi ideas. This is the work that the aged Shaykh gave Maulana Jalal ad-Din Rumi when Rumi's family stayed over at Nishapur on its way to Konya, Turkey. | *Asrar Nameh (Book of Secrets) about Sufi ideas. This is the work that the aged Shaykh gave Maulana Jalal ad-Din Rumi when Rumi's family stayed over at Nishapur on its way to Konya, Turkey. | ||

*Elahi Nameh (Divine Book), about zuhd or asceticism. In this book `Attar framed his mystical teachings in various stories that a caliph tells his six sons, who are kings themselves and seek worldly pleasures and power. The book also contains praises of [[Sunni|Sunni Islam's]] four [[Rashidun|Rightly Guided Caliphs]].<ref>Red-Sulphur.org: `Attar's praise of Hadrat Abu Bakr | url = http://red-sulphur.org/?q=node/491</ref> | *Elahi Nameh (Divine Book), about zuhd or asceticism. In this book `Attar framed his mystical teachings in various stories that a caliph tells his six sons, who are kings themselves and seek worldly pleasures and power. The book also contains praises of [[Sunni|Sunni Islam's]] four [[Rashidun|Rightly Guided Caliphs]].<ref>Red-Sulphur.org: `Attar's praise of Hadrat Abu Bakr | url = http://red-sulphur.org/?q=node/491</ref> | ||

| − | *[[Conference of the Birds|Manteq al-Tayr]] ( | + | *[[Conference of the Birds|Manteq al-Tayr]] (Conference of the Birds) in which he makes extensive use of Al-Ghazali's Risala on Birds as well as a treatise by the Ikhvan al-Safa (the Brothers of Serenity) on the same topic. |

*Tadhkirat al-Auliya (The Memorial of the Saints). In this famous book, `Attar recounts the life stories of famous [[Muslim saints]], among them the four Imams of [[madhab|Sunni jurisprudence]], from the early period of [[Islam]]. He also praises Imam Jafar Assadiq and Imam Baghir as two Imams of the Shai muslims. | *Tadhkirat al-Auliya (The Memorial of the Saints). In this famous book, `Attar recounts the life stories of famous [[Muslim saints]], among them the four Imams of [[madhab|Sunni jurisprudence]], from the early period of [[Islam]]. He also praises Imam Jafar Assadiq and Imam Baghir as two Imams of the Shai muslims. | ||

====Manteq al-Tayr (Conversation of the Birds)==== | ====Manteq al-Tayr (Conversation of the Birds)==== | ||

| − | Led by the hoopoe, the birds of the world set forth in search of their king, [[Simurgh]]. Their quest takes them through seven valleys in the first of which a hundred difficulties assail them. They undergo many trials as they try to free themselves of what is precious to them and change their state. Once successful and filled with longing, they ask for wine to dull the effects of dogma, belief, and unbelief on their lives. In the second valley, the birds give up reason for love and, with a thousand hearts to sacrifice, continue their quest for discovering the Simurgh. The third valley confounds the birds, especially when they discover that their worldly knowledge has become completely useless and their understanding has become ambivalent. There are different ways of crossing this Valley, and all birds do not fly alike. Understanding can be arrived at | + | Led by the hoopoe, the birds of the world set forth in search of their king, [[Simurgh]]. Their quest takes them through seven valleys in the first of which a hundred difficulties assail them. They undergo many trials as they try to free themselves of what is precious to them and change their state. Once successful and filled with longing, they ask for wine to dull the effects of dogma, belief, and unbelief on their lives. In the second valley, the birds give up reason for love and, with a thousand hearts to sacrifice, continue their quest for discovering the Simurgh. The third valley confounds the birds, especially when they discover that their worldly knowledge has become completely useless and their understanding has become ambivalent. There are different ways of crossing this Valley, and all birds do not fly alike. Understanding can be arrived at variously—some have found the Mihrab, others the idol. |

The fourth valley is introduced as the valley of detachment, i.e., detachment from desire to possess and the wish to discover. The birds begin to feel that they have become part of a universe that is detached from their physical recognizable reality. In their new world, the planets are as minute as sparks of dust and elephants are not distinguishable from ants. It is not until they enter the fifth valley that they realize that unity and multiplicity are the same. And as they have become entities in a vacuum with no sense of eternity. More importantly, they realize that God is beyond unity, multiplicity, and eternity. Stepping into the sixth valley, the birds become astonished at the beauty of the Beloved. Experiencing extreme sadness and dejection, they feel that they know nothing, understand nothing. They are not even aware of themselves. Only thirty birds reach the abode of the Simurgh. But there is no Simurgh anywhere to see. Simurgh's chamberlain keeps them waiting for Simurgh long enough for the birds to figure out that they themselves are the ''si'' (thirty) ''murgh'' (bird). The seventh valley is the valley of depravation, forgetfulness, dumbness, deafness, and death. The present and future lives of the thirty successful birds become shadows chased by the celestial Sun. And themselves, lost in the Sea of His existence, are the Simurgh<ref>[http://www.angelfire.com/rnb/bashiri/Poets/Attar.html Central Asia and Iran<!-- Bot generated title —>]</ref>. The poem's title possibly served as inspiration for [[jazz]] bassist [[Dave Holland]]'s 1972 album of the same name. | The fourth valley is introduced as the valley of detachment, i.e., detachment from desire to possess and the wish to discover. The birds begin to feel that they have become part of a universe that is detached from their physical recognizable reality. In their new world, the planets are as minute as sparks of dust and elephants are not distinguishable from ants. It is not until they enter the fifth valley that they realize that unity and multiplicity are the same. And as they have become entities in a vacuum with no sense of eternity. More importantly, they realize that God is beyond unity, multiplicity, and eternity. Stepping into the sixth valley, the birds become astonished at the beauty of the Beloved. Experiencing extreme sadness and dejection, they feel that they know nothing, understand nothing. They are not even aware of themselves. Only thirty birds reach the abode of the Simurgh. But there is no Simurgh anywhere to see. Simurgh's chamberlain keeps them waiting for Simurgh long enough for the birds to figure out that they themselves are the ''si'' (thirty) ''murgh'' (bird). The seventh valley is the valley of depravation, forgetfulness, dumbness, deafness, and death. The present and future lives of the thirty successful birds become shadows chased by the celestial Sun. And themselves, lost in the Sea of His existence, are the Simurgh<ref>[http://www.angelfire.com/rnb/bashiri/Poets/Attar.html Central Asia and Iran<!-- Bot generated title —>]</ref>. The poem's title possibly served as inspiration for [[jazz]] bassist [[Dave Holland]]'s 1972 album of the same name. | ||

| Line 109: | Line 87: | ||

`Attar is one of the most famous [[mysticism|mystic]] poets of Iran. His works were the inspiration of [[Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi|Rumi]] and many other mystic poets. `Attar, along with [[Sanai]] were two of the greatest influences on Rumi in his [[Sufi]] views. Rumi has mentioned both of them with the highest esteem several times in his poetry. Rumi praises `Attar as such: | `Attar is one of the most famous [[mysticism|mystic]] poets of Iran. His works were the inspiration of [[Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi|Rumi]] and many other mystic poets. `Attar, along with [[Sanai]] were two of the greatest influences on Rumi in his [[Sufi]] views. Rumi has mentioned both of them with the highest esteem several times in his poetry. Rumi praises `Attar as such: | ||

| − | : "''Attar roamed the seven cities of | + | : "''Attar roamed the seven cities of love—We are still just in one alley''".<ref>Aghevli, page 15.</ref> |

Rumi is said to have met Attar during his childhood, who "dandled him on his knee."<ref>Darbandi and Davis, page 12.</ref> | Rumi is said to have met Attar during his childhood, who "dandled him on his knee."<ref>Darbandi and Davis, page 12.</ref> | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 125: | Line 102: | ||

* ʻAṭṭār, Farīd al-Dīn, and A. J. Arberry. 1966. ''Muslim saints and mystics. UNESCO collection of representative works: Persian heritage series.'' [Chicago]: University of Chicago Press. {{OCLC|395176}} | * ʻAṭṭār, Farīd al-Dīn, and A. J. Arberry. 1966. ''Muslim saints and mystics. UNESCO collection of representative works: Persian heritage series.'' [Chicago]: University of Chicago Press. {{OCLC|395176}} | ||

* ʻAṭṭār, Farīd al-Dīn, Kenneth Avery, and Ali Alizadeh. 2007. ''Fifty poems of ʻAṭṭār.'' Anomaly. Seddon, Vic: re.press. ISBN 9780980305210. | * ʻAṭṭār, Farīd al-Dīn, Kenneth Avery, and Ali Alizadeh. 2007. ''Fifty poems of ʻAṭṭār.'' Anomaly. Seddon, Vic: re.press. ISBN 9780980305210. | ||

| + | * Field, Claude. 2007. ''The Confessions of Al Ghazzali; Mystics.'' EastbourneGardners Books. ISBN 9780548080177. | ||

* Davis, Dick and Darbandi, Afkham. 1984. "Introduction." 9-26. ''The conference of the birds.'' The Penguin classics. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140444346. | * Davis, Dick and Darbandi, Afkham. 1984. "Introduction." 9-26. ''The conference of the birds.'' The Penguin classics. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140444346. | ||

| + | * Lewisohn, Leonard, and C. Shackle. 2006. 'Aṭṭār and the Persian Sufi tradition: the art of spiritual flight. London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 9781845111489. | ||

| + | * Ritter, Hellmut, John O'Kane, and Bernd Radtke. 2003. ''The ocean of the soul: man, the world, and God in the stories of Farīd al-Dīn ʻAṭṭār.'' Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004120686. | ||

* Smith, Margaret, and Farīd al-Dīn ʻAṭṭār. 1995. ''The Persian mystics: 'Aṭṭār. The Wisdom of the East.'' Felinfach: Llanerch. ISBN 9781897853924. | * Smith, Margaret, and Farīd al-Dīn ʻAṭṭār. 1995. ''The Persian mystics: 'Aṭṭār. The Wisdom of the East.'' Felinfach: Llanerch. ISBN 9781897853924. | ||

| Line 155: | Line 135: | ||

[[Category:Sufi poets]] | [[Category:Sufi poets]] | ||

[[Category:Sufi fiction]] | [[Category:Sufi fiction]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Credit|227838879}} | {{Credit|227838879}} | ||

Revision as of 18:25, 13 January 2009

Abū Hamīd bin Abū Bakr Ibrāhīm (1120- in Nishapur – died c. 1229), much better known by his pen-names Farīd ud-Dīn (Persian: فریدالدین) and ‘Attār (Persian: عطار - "the pharmacist"), was a Persian and Muslim [[poetry|poet, Sufi, theoretician of mysticism, and hagiographer.

Biography

Information about `Attar's life is rare. He is mentioned by only two of his contemporaries, `Awfi and Khadja Nasir ud-Din Tusi. However, all sources confirm that he was from Nishapur, a major city of medieval Khorasan (now located in the northeast of Iran), and according to `Awfi, he was a poet of the Seljuq period. Darbandi and Davis cite 1120 as his possible birth date, commenting that sources indicate a date between 1120 and 1157.[1] It seems that he was not well known as a poet in his own lifetime, except at his home town, and his greatness as a mystic, a poet, and a master of narrative was not discovered until the 15th century.

Life

`Attar was probably the son of a prosperous chemist, receiving an excellent education in various fields. He is said to have attended "the theological school attached to the shrine of Imam Reza at Mashhad."[2] While his works say little else about his life, they tell us that he practiced the profession of pharmacy and personally attended to a very large number of customers. The people he helped in the pharmacy used to confide their troubles in `Attar, which affected him deeply. Eventually, he abandoned his pharmacy store and traveled widely - to Kufa, Mecca, Damascus, Turkistan, and India, meeting with Sufi Shaykhs - then returned, promoting Sufi ideas. Such travel in search of knowledge was not uncommon for Sufi practitioners at the time.

On the one hand, `Attar is renowned as a Sufi thinker and writer, on the other hand his exact relationship with any Sufi teacher or order is vague. It is not known for certain which Sufi master instructed him. Possibly, his teacher was Majd ad-Din al-Baghdadi (d. 1219) although Baghdadi may have taught him medicine not theology. A tradition "first mentioned by Rumi has it that he "had no teacher and was instructed in the Way by the spirit of Mansur al-Hallaj, the Sufi martyr who had been executed in Baghdad in 922 and who appeared to him in a dream." Or, he may have joined a Sufi order then received a "confirmatory dream in which Hallaj appeared to him." Darbandi and Davis suggest that reference to the spirit of Hallaj may be a "dramaticv symbol of his scholarly pre-occupation with the lives of dead saints."[3]

It can, though, be taken for granted that from childhood onward `Attar, encouraged by his father, was interested in the Sufis and their sayings and way of life, and regarded their saints as his spiritual guides. `Attar "boasted that he had never sought a king's favour or stooped to writing a panegyric" which "alone would make him worthy of note among Persian poets."[4] `Attar probably supported himself from his work as a chemist or physician. `Attar means herbalist, druggist and perfumist, and during his lifetime in Persia, much of medicine and drugs were based on herbs. He says that he "composed his poems in his daru-khane" which means "a chemist's shop or drug-store, but which has suggestions of a dispensary or even a doctor's surgery." It is probable that he "combined the selling of drugs and perfumes with the practice of medicine."[5]

Death

`Attar reached an age of over 70 (some sources mention 110) and died a violent death in the massacre which the Mongols inflicted on Nishabur in April 1229 although possible death dates range from 1193 to 1235.[6] His mausoleum, built by Ali-Shir Nava'i in the 16th century, is located in Nishapur.

Like many aspects of his life, his death, too, is blended with legends and speculation. A well-known story regarding his death goes as follows:

During the invasion of Persia by Jenghis Khan (1229 C.E.) when `Attar had reached the age of 110, he was taken prisoner by the Mongols. One of them was about to kill him, when another said "let the old man live; I will give a thousand pieces of silver as his ransom. His captor was about to close with the bargain, but `Attar said, "Don't sell me as chaeaply; you will find someone willing to give more." Subsequently, another man came up and offered a bag of straw for him. "Sell me to him," said `Attar, for that is all I am worth." The Mongol, irritated at teh loss of the first offer, slew him, who thus found the death he desired.[7]

Teachings

The thought-world depicted in `Attar's works reflects the whole evolution of the Sufi movement. The starting point is the idea that the body-bound soul's awaited release and return to its source in the other world can be experienced during the present life in mystic union attainable through inward purification. By explaining his thoughts, the material uses is not only from specifically Sufi but also from older ascetic legacies. Although his heroes are for the most part Sufis and ascetics, he also introduces stories from historical chronicles, collections of anecdotes, and all types of high-esteemed literature. His talent for perception of deeper meanings behind outward appearances enables him to turn details of everyday life into illustrations of his thoughts. The idiosyncrasy of `Attar's presentations invalidates his works as sources for study of the historical persons whom he introduces. As sources on the hagiology and phenomenology of Sufism, however, his works have immense value.

Judging from `Attar's writings, he viewed philosophy with skepticism and dislike. He wrote, "No one is farther from the Arabian prophet than the philosopher. Know that philosophy (falsafa) is the wont and way of Zoroaster, for philosophy is to turn your back on all religious law."[8] Interestingly, he did not want to uncover the secrets of nature. This is particularly remarkable in the case of medicine, which fell within the scope of his profession. He obviously had no motive for showing off his secular knowledge in the manner customary among court panegyrists, whose type of poetry he despised and never practiced. Such knowledge is only brought into his works in contexts where the theme of a story touches on a branch of natural science.

Poetry

`Attar speaks of his own poetry in various contexts including the epilogues of his long narrative poems. He confirms the guess likely to be made by every reader that he possessed an inexhaustible fund of thematic and verbal inspiration. He writes that when he composed his poems, more ideas came into his mind than he could possibly use.

Like his contemporary Khaqani, `Attar was not only convinced that his poetry had far surpassed all previous poetry, but that it was to be intrinsically unsurpassable at any time in the future, seeing himself as the “seal of the poets” and his poetry as the “seal of speech.”[9]

Works

The question whether all the works that have been ascribed to him are really from his pen, has not been solved. This is due to two facts that have been observed in his works:

- There are considerable differences of style among these works.

- Some of them indicate a Sunnite, and others a Shia, allegiance of the author.

Classification of the various works by these two criteria yields virtually identical results. The German orientalist Hellmut Ritter at first thought that the problem could be explained by a spiritual evolution of the poet. He distinguished three phases of `Attar's creativity:

- Works in which mysticism is in perfect balance with a finished, story-teller's art.

- Works in which a pantheistic zeal gains the upper hand over literary interest.

- Works in which the aging poet idolizes Imam Ali ibn Abu Talib while there is no trace of ordered thoughts and descriptive skills.

Phrase three may be coincidental with a conversion to Shi'ism.[10] However, in 1941, the Persian scholar Nafisi was able to prove that the works of the third phase in Ritter's classification were written by another `Attar who lived about two hundred and fifty years later at Mashhad and was a native of Tun. Ritter accepted this finding in the main, but doubted whether Nafisi was right in attributing the works of the second group also to this `Attar of Tun. One of Ritter's arguments is that the principal figure in the second group is not Ali, as in the third group, but Hallaj, and that there is nothing in the explicit content of the second group to indicate a Shia allegiance of the author. Another is the important chronological point that a manuscript of the Jawhar al-Dāt, the chief work in the second group, bears the date 735 A.H. (= 1334-35 C.E.). While `Attar of Tun's authorship of the second group is untenable, Nafisi was certainly right in concluding that the style difference (already observed by Ritter) between the works in the first group and those in the second group is too great to be explained by a spiritual evolution of the author. The authorship of the second group remains an unsolved problem.[11]

In the introductions of Mokhtār-Nāma and Khosrow-Nāma, `Attar lists the titles of further products of his pen:

- Dīvān

- Asrār-Nāma

- Maqāmāt-e Toyūr (= Manteq al-Ṭayr)

- Moṣībat-Nāma

- Elāhī-Nāma

- Jawāher-Nāma'

- Šarḥ al-Qalb[12]

He also states, in the introduction of the Mokhtār-Nāma, that he destroyed the Jawāher-Nāma' and the Šarḥ al-Qalb with his own hand.

Although the contemporary sources confirm only `Attar's authorship of the Dīvān and the Manteq al-Ṭayr, there are no grounds for doubting the authenticity of the Mokhtār-Nāma and Khosrow-Nāma and their prefaces.[11] One work is missing from these lists, namely the Tadkerat al-Awlīya, which was probably omitted because it is a prose work; its attribution to `Attar is scarcely open to question. In its introduction `Attar mentions three other works of his, including one entitled Šarḥ al-Qalb, presumably the same that he destroyed. The nature of the other two, entitled Kašf al-Asrār and Ma'refat al-Nafs, remains unknown.[13]

In the following, the authentic works are discussed separately:

- Asrar Nameh (Book of Secrets) about Sufi ideas. This is the work that the aged Shaykh gave Maulana Jalal ad-Din Rumi when Rumi's family stayed over at Nishapur on its way to Konya, Turkey.

- Elahi Nameh (Divine Book), about zuhd or asceticism. In this book `Attar framed his mystical teachings in various stories that a caliph tells his six sons, who are kings themselves and seek worldly pleasures and power. The book also contains praises of Sunni Islam's four Rightly Guided Caliphs.[14]

- Manteq al-Tayr (Conference of the Birds) in which he makes extensive use of Al-Ghazali's Risala on Birds as well as a treatise by the Ikhvan al-Safa (the Brothers of Serenity) on the same topic.

- Tadhkirat al-Auliya (The Memorial of the Saints). In this famous book, `Attar recounts the life stories of famous Muslim saints, among them the four Imams of Sunni jurisprudence, from the early period of Islam. He also praises Imam Jafar Assadiq and Imam Baghir as two Imams of the Shai muslims.

Manteq al-Tayr (Conversation of the Birds)

Led by the hoopoe, the birds of the world set forth in search of their king, Simurgh. Their quest takes them through seven valleys in the first of which a hundred difficulties assail them. They undergo many trials as they try to free themselves of what is precious to them and change their state. Once successful and filled with longing, they ask for wine to dull the effects of dogma, belief, and unbelief on their lives. In the second valley, the birds give up reason for love and, with a thousand hearts to sacrifice, continue their quest for discovering the Simurgh. The third valley confounds the birds, especially when they discover that their worldly knowledge has become completely useless and their understanding has become ambivalent. There are different ways of crossing this Valley, and all birds do not fly alike. Understanding can be arrived at variously—some have found the Mihrab, others the idol.

The fourth valley is introduced as the valley of detachment, i.e., detachment from desire to possess and the wish to discover. The birds begin to feel that they have become part of a universe that is detached from their physical recognizable reality. In their new world, the planets are as minute as sparks of dust and elephants are not distinguishable from ants. It is not until they enter the fifth valley that they realize that unity and multiplicity are the same. And as they have become entities in a vacuum with no sense of eternity. More importantly, they realize that God is beyond unity, multiplicity, and eternity. Stepping into the sixth valley, the birds become astonished at the beauty of the Beloved. Experiencing extreme sadness and dejection, they feel that they know nothing, understand nothing. They are not even aware of themselves. Only thirty birds reach the abode of the Simurgh. But there is no Simurgh anywhere to see. Simurgh's chamberlain keeps them waiting for Simurgh long enough for the birds to figure out that they themselves are the si (thirty) murgh (bird). The seventh valley is the valley of depravation, forgetfulness, dumbness, deafness, and death. The present and future lives of the thirty successful birds become shadows chased by the celestial Sun. And themselves, lost in the Sea of His existence, are the Simurgh[15]. The poem's title possibly served as inspiration for jazz bassist Dave Holland's 1972 album of the same name.

`Attar's Seven Valleys of Love

- The Valley of Quest

- The Valley of Love

- The Valley of Understanding

- The Valley of Independence and Detachment

- The Valley of Unity

- The Valley of Astonishment and Bewilderment

- The Valley of Deprivation and Death

Tadhkirat al-awliya (The Memorial of the Saints)

Attar's only known prose work which he worked on throughout much of his life and which was available publicly before his death, is a biography of muslim saints and mystics. In what is considered the most compelling entry in this book, `Attar relates the story of the execution of Hallaj, the mystic who had uttered the words “I am the Truth” in a state of ecstatic contemplation.

Influence on Rumi

`Attar is one of the most famous mystic poets of Iran. His works were the inspiration of Rumi and many other mystic poets. `Attar, along with Sanai were two of the greatest influences on Rumi in his Sufi views. Rumi has mentioned both of them with the highest esteem several times in his poetry. Rumi praises `Attar as such:

- "Attar roamed the seven cities of love—We are still just in one alley".[16]

Rumi is said to have met Attar during his childhood, who "dandled him on his knee."[17]

Notes

- ↑ Darbandi and Davis, page 9.

- ↑ Darbandi and Davis, page 9.

- ↑ Darbandi and Davis, page 12.

- ↑ Darbandi and Davis, pages 9-10.

- ↑ Drabandi and Davis, page 9.

- ↑ Darbandi and Davis, page 10.

- ↑ Field, pages 139-140.

- ↑ Lewisohn, page xx citing from `Attar's Book of Adversity.

- ↑ Lewisohn, page 334.

- ↑ Rittner,

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedIranica- ↑ quoted in H. Ritter, “Philologika X,” pp. 147-53

- ↑ Ritter, “Philologika XIV,” p. 63

- ↑ Red-Sulphur.org: `Attar's praise of Hadrat Abu Bakr | url = http://red-sulphur.org/?q=node/491

- ↑ Central Asia and Iran

- ↑ Aghevli, page 15.

- ↑ Darbandi and Davis, page 12.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aghevli, J. D. 1998. Garden of the Sufi: insights into the nature of man. Atlanta: Humanics Pub. ISBN 9780893342692.

- Behari, Bankey, Chhanganlal Lala, Abū al-Majd Majdūd ibn Ādam Sanāʼī al-Ghaznavī, Farīd al-Dīn ʻAṭṭār, and Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī. 1998. The immortal Sufi triumvirate: Sanāi, Attār, Rumi. Delhi: B.R. Pub. Corp. ISBN 9788176460156.

- ʻAṭṭār, Farīd al-Dīn, Dick Davis, and Afkham Darbandi. 1984. The conference of the birds. The Penguin classics. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140444346.

- ʻAṭṭār, Farīd al-Dīn, and A. J. Arberry. 1966. Muslim saints and mystics. UNESCO collection of representative works: Persian heritage series. [Chicago]: University of Chicago Press. OCLC 395176

- ʻAṭṭār, Farīd al-Dīn, Kenneth Avery, and Ali Alizadeh. 2007. Fifty poems of ʻAṭṭār. Anomaly. Seddon, Vic: re.press. ISBN 9780980305210.

- Field, Claude. 2007. The Confessions of Al Ghazzali; Mystics. EastbourneGardners Books. ISBN 9780548080177.

- Davis, Dick and Darbandi, Afkham. 1984. "Introduction." 9-26. The conference of the birds. The Penguin classics. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140444346.

- Lewisohn, Leonard, and C. Shackle. 2006. 'Aṭṭār and the Persian Sufi tradition: the art of spiritual flight. London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 9781845111489.

- Ritter, Hellmut, John O'Kane, and Bernd Radtke. 2003. The ocean of the soul: man, the world, and God in the stories of Farīd al-Dīn ʻAṭṭār. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004120686.

- Smith, Margaret, and Farīd al-Dīn ʻAṭṭār. 1995. The Persian mystics: 'Aṭṭār. The Wisdom of the East. Felinfach: Llanerch. ISBN 9781897853924.

See also

- List of Persian poets and authors

- Persian literature

- Sufism

- Seven Valleys

- Mastan Ensemble

External links

- Attar, Farid ad-Din. A biography by Professor Iraj Bashiri, University of Minnesota.

- `Attar's poem in Praise of Prophet Muhammad

- Poetry by `Attar

- Fifty Poems of `Attar. A Translation of 50 poems with the Persian on the facing page, re.press ADVERT

Persian literature

900s–1000s Rūdakī · Daqīqī · Ferdowsī (Šahnāma) · Abu Shakur Balkhi · Bal'ami · Rabia Balkhi · Abusaeid Abolkheir (967–1049) · Avicenna (980–1037) · Unsuri · Asjadi · Kisai Marvazi · Ayyuqi 1000s–1100s Bābā Tāher · Nasir Khusraw (1004–1088) · Al-Ghazali (1058–1111) · Khwaja Abdullah Ansari (1006–1088) · Asadi Tusi · Qatran Tabrizi (1009–1072) · Nizam al-Mulk (1018–1092) · Masud Sa'd Salman (1046–1121) · Moezi Neyshapuri · Omar Khayyām (1048–1131) · Fakhruddin As'ad Gurgani · Hujwiri · Manuchehri · Ayn-al-Quzat Hamadani (1098–1131) · Uthman Mukhtari · Abu-al-Faraj Runi · Sanai · Mu'izzi · Mahsati Ganjavi 1100s–1200s Hakim Iranshah · Suzani Samarqandi · Ashraf Ghaznavi · Shahab al-Din Suhrawardi (1155–1191) · Adib Sabir · Am'aq · Attār (1142–c.1220) · Khaghani (1120–1190) · Anvari (1126–1189) · Faramarz-e Khodadad · Nizāmī Ganjavi (1141–1209) · Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (1149–1209) · Shams Tabrizi (d.1248) 1200s–1300s Abu Tahir Tartusi · Najm al-din Razi · Awhadi Maraghai · Shams al-Din Qays Razi · Baha al-din Walad · Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī · Baba Afdal al-Din Kashani · Fakhr al-din Araqi · Mahmud Shabistari (1288–1320s) · Abu'l Majd Tabrizi · Amīr Khosrow (1253–1325) · Sa'adī (Būstān / Golestān) · Bahram-e-Pazhdo · Zartosht Bahram e Pazhdo · Rumi · Homam Tabrizi (1238–1314) · Khwaju Kermani · Sultan Walad 1300s–1400s Ibn Yamin · Shah Ni'matullah Wali · Hāfez (Dīvān) · Abu Ali Qalandar · Fazlallah Astarabadi · Nasimi · Emad al-Din Faqih Kemani 1400s–1500s Ubayd Zakani · Salman Sawaji · Jāmī · Kamal Khujandi · Ahli Shirzi (1454–1535) · Fuzûlî (1483–1556) · Baba Faghani Shirzani 1500s–1600s Vahshi Bafqi (1523–1583) · Urfi Shirazi 1600s–1700s Sa'eb Tabrizi (1607–1670) · Hazin Lāhiji (1692–1766) · Saba Kashani · Bidel Dehlavi (1642–1720) 1700s–1800s Neshat Esfahani · Forughi Bistami (1798–1857) · Mahmud Saba Kashani (1813–1893)

Contemporary Persian and Classical Persian are the same language, but writers since 1900 are classified as contemporary. The above lists include poets mostly of Iranic background but also some of Indic, Turkic and Slavic backgrounds. At one time, Persian was a common cultural language of much of the non-Arabic Islamic world.

Topics in Sufism Sufi philosophy: Practices: Sufi orders: Medieval Sufis: Notable Modern Sufis: Sufi studies: Miscellaneous: Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.