Rabia Basri

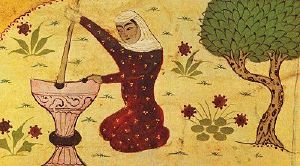

Rābiʻa al-ʻAdawiyya al-Qaysiyya (Arabic: رابعة العدوية القيسية) or simply Rabiʿa al-Basri (717–801 C.E.) was a female Muslim Sufi saint, considered by some to be the first true saint in the Sufi tradition. Little is known of her life apart from her piety, popularity with men and women followers of the Sufi path, and her refusal to marry. The birth and death dates given for her are only approximate. She was orphaned then sold as a slave in her youth then set free by her Master to practice devotion and to engage in prayer. Many stories of her life were later told by Farid ad-Din Attar. She is associated in legend with Hassan of Basri as his pupil or even as his teacher, although it is unlikely that they met, since he died in 728, when she was still a child. The numerous stories of her piety, love for God, of people and of her ascetic life-style attest to the significance of her life in the story of the development of mystical Islam. Among women, perhaps only the wives of Muhammad, known as mothers of the believers, occupy so honored a place in the hearts of Muslims around the world.

Her reputation excels that of many Muslim men within the early days of Sufism; she "belongs to that elect company of Sufi women who have surpassed most of the contemporary masters of their time in wayfaring to God." She has been described as symbolizing "saintliness among women Sufis."[1] Her love mysticism, which she is widely credited as pioneering, triumphed over other expressions that feared God rather than adored the divine. She was a teacher of men as well as of women, a women who called no man her master, indeed whose surrender to God was so complete that she placed all her trust in God to ensure that she was fed and clothed. Her devotion to God was so intense that relatively few solid facts about her life survived except that it was lived in complete and loving surrender to God, which is the Islamic path.

Life

Early Life

She was born between 95 and 99 Hijri in Basra, Iraq. Much of her early life is narrated by Farid al-Din Attar. Many spiritual stories are associated with her and it is sometimes difficult to separate reality from legend. These traditions come from Farid al-Din Attar, a later sufi saint and poet, who used earlier sources. He is believed to have possessed a lost monograph on "her life and acts".[2] Rabia herself did not leave any written works.

She was the fourth daughter of her family and therefore named Rabia, meaning "fourth." She was born free in a poor but respected family. According to Nurbakhsh, though poor, her family could trace its lineage back to Noah.[3]

According to Farid al-Din Attar, Rabia's parents were so poor that there was no oil in house to light a lamp, nor a cloth even to wrap her with. Her mother asked her husband to borrow some oil from a neighbor, but he had resolved in his life never to ask for anything from anyone except the Creator. He pretended to go to the neighbor's door and returned home empty-handed.[4]

In the night Prophet appeared to him in a dream and told him:

Your newly born daughter is a favorite of the Lord, and shall lead many Muslims to the right path. You should approach the Amir of Basra and present him with a letter in which should be written this message: "You offer Durood to the Holy Prophet one hundred times every night and four hundred times every Thursday night. However, since you failed to observe the rule last Thursday, as a penalty you must pay the bearer four hundred dinars."

Rabia's father got up and went straight to the Amir with tears of joy rolling down his cheeks. The Amir was delighted on receiving the message, knowing that he was in the eyes of Prophet. He distributed 1000 dinars to the poor and joyously paid 400 dinars to Rabia's father. The Amir then asked Rabia's father to come to him whenever he required anything, as the Amir would benefit very much by the visit of such a soul dear to the Lord.[5]

After the death of her father a famine Basra experienced a famine. Separated from her sisters, legend has it that Rabia was accompanying a caravan, which fell into the hands of robbers. The chief of the robbers took Rabia captive, and sold her in the market as a slave. Her "purchaser put her to hard labor."[6]

She would pass the whole night in prayer, after she had finished her household jobs. She spent many of her days observing a fast.[7]

Once the master of the house got up in the middle of the night, and was attracted by the pathetic voice in which Rabia was praying to her Lord. She was entreating in these terms:

"O my Lord, Thous knowest that the desire of my heart is to obey Thee, and that the light of my eye is in the service of Thy court. If the matter rested with me, I should not cease for one hour from Thy service, but Thou hast made me subject to a creature"[8]

At once the master felt that it was sacrilegious to keep such a saint in his service. He decided to serve her instead. In the morning he called her and told her his decision; he would serve her and she should dwell there as the mistress of the house. If she insisted on leaving the house he was willing to free her from bondage.[7]

She told him that she was willing to leave the house to carry on her worship in solitude. The master granted this and she left the house.

Ascetic and teacher

Rabia went into the desert to pray, spending some time at a Sufi hermitage. She then began what according to Farīd al-Dīn was a seven year walk (some accounts describe her as crawling on her stomach) to Mecca, to perform the Hajj. According to Farīd al-Dīn, as she approached the Ka'bah, her monthly period began, which made her unclean and unable to continue that day. Farīd al-Dīn uses this as lesson that even such a great saint as Rabia was "hindered on the way."[9] Another story has the Ka'bah coming to greet her even as she persevered in her journey yet she ignored it, since her desire was for the "House of the Lord" alone, "I pay no attention to the Ka'bah and enjoy not its beauty. My only desire is to encounter Him who said, 'Whosoever approaches Me by a span, I will approach him by a cubit'."[10]

It is unclear whether Rabia received formal instruction in the Sufi way. Legend persistently associates her with Hasan of Basra, although their probable chronologies make this impossible. Hasan is sometimes described as her master although other stories suggest that her station along the path was more advanced. For example:

One day, she was seen running through the streets of Basra carrying a torch in one hand and a bucket of water in the other. When asked what she was doing, she said:

“Hasan,” Rabe’a replied, “when you are showing off your spiritual goods in this worldly market, it should be things that your fellow-men are incapable of displaying.” And she flung her prayer rug into the air, and flew up on it. “Come up here, Hasan, where people can see us!” she cried. Hasan, who had not attained that station, said nothing. Rabe’a sought to console him. “Hasan,” she said, “what you did fishes also do, and what I did flies also do. The real business is outside both these tricks. One must apply one’s self to the real business.”[11]

El Sakkakini suggests that it would have been from Sufi circles in Basra that Rabia received instruction;

It is also likely that Rabia, in her first encounter with Sufi circles at an early age, participated in playing the nay, at type of reed pipe or flute. This type of music was an integral part of ancient Sufi movements which are still in existence today … Rabia's Sufism developed as a result of her inborn capacity … not only from being taught, or from initiating.[12]

According to El Sakkakini, Rabia can also be considered the first Sufi teacher who taught by using "demonstration," that is, by "object lesson."[13] As her fame grew she attracted many disciples. This suggests that she was recognized as a teacher in her own right. It is widely held that she achieved self-actualization, the end of the mystical path, that is, the total passing away of the self into complete intimacy and unity with the divine truth. She also had discussions with many of the renowned religious people of her time. She may have established her own hermitage, where she gave instruction, although this is not clear.

Her life was totally devoted to love of God, the ascetic life and self-denial. Her reputation for asceticism survives through numerous stories. It is said that her only possessions were a broken jug, a rush mat and a brick, which she used as a pillow. She spent all night in prayer and contemplation, reciting the Qur'an and chided herself if she fell asleep because it took her away from her active Love of God.[14]

More interesting than her absolute asceticism, however, is the concept of Divine Love that Rabia introduced. She was the first to introduce the idea that God should be loved for God's own sake, not out of fear—as earlier Sufis had done. "She was," says El Sakkakini, "the first to explain the Higher Love in Islamic Sufism."[15] Margoliouth wrote:

The purely ascetic way of life did not remain a goal in itself. In the middle of the eight century, the first signs of genuine love mysticism appears among the pious. Its first representative was a woman, Rabi'a of Basra.[16]

Teaching

She taught that repentance was a gift from God because no one could repent unless God had already accepted him and given him this gift of repentance. Sinners, she said, must fear the punishment they deserved for their sins but she also offered sinners far more hope of Paradise than most other ascetics did. Intimacy with God was not the result of "work" but of self-abandonment; it is God who draws near to those who love God, not the lover who draws near to the beloved. For herself, she held to a higher ideal, worshiping God neither from fear of Hell nor from hope of Paradise, for she saw such self-interest as unworthy of God's servants; emotions like fear and hope were like veils—that is, hindrances to the vision of God Himself.

She prayed:

"O Allah! If I worship You for fear of Hell, burn me in Hell,

and if I worship You in hope of Paradise, exclude me from Paradise.

But if I worship You for Your Own sake,

grudge me not Your everlasting Beauty.”[17]

Much of the poetry that is attributed to her is of unknown origin. Gibb comments that she preferred the "illuminative from the contemplative life," which in his opinion is closer to and perhaps derived from Christian mysticism.[18] As Bennett comments, non-Muslims have often attributed the development of love-mysticism in Islam to external influence yet "not a few Qur'anic verses speak of God as a 'lover:' for example,Q5: 54, 'Allah will bring a people whom He loveth and who love Him'; other verses, for example Q2: 165, speaks of the believers 'love for God'."[19]

The question of marriage

Though she had many offers of marriage, and (tradition has it) one even from the Amir of Basra, she refused them as she had no time in her life for anything other than God. One story has the Prophet Muhammad asking her in a dream whether she loved him, to which she replied:

"O prophet of God, who is there who does not love thee? But my love to God has so possessed me that no place remains for loving or hating any save Him," which suggests that love for any man would represent a distraction for her from loving God.[20]

Hasan of Basra is also reputed to have asked her to marry him.[21] “Do you desire for us to get married?” Hasan asked Rabe’a. “The tie of marriage applies to those who have being,” Rabe’a replied. “Here being has disappeared, for I have become naughted to self and exist only through Him. I belong wholly to Him. I live in the shadow of His control. You must ask my hand of Him, not of me.” “How did you find this secret, Rabe’a?” Hasan asked. “I lost all ‘found’ things in Him,” Rabe’a answered. “How do you know Him?” Hasan enquired. “You know the ‘how’; I know the ‘howless’,” Rabe’a "You know of the how, but I know of the how-less." [22]

Death

Rabia was in her early to mid eighties when she died, having followed the mystic Way to the end. She believed she was continually united with her Beloved. As she told her Sufi friends, "My Beloved is always with me." As she passed away, those present heard a voice saying, "O soul at peace, return unto Thy lord, well pleased."[23]

Rabi'a' and the Issue of Gender

Marriage is considered a duty in Islam, not an option. However, Rabia is never censored in any of the literature for having remained celibate. In including her as a saint in his series of biographical sketches, Farid al-Din Attar does begin on a defensive note:

<blockquote?

If anyone asks, "why have you included Rabe'a in the rank of men?' my answer is, that the prophet himself said, 'God does not regard your outward forms ...' Moreover, if it is permissible to derive two-thirds of our religion from A'esha, surely it is permissible to take religious instruction from a handmaid of A'esha."[24] Rabia, said al-Din Attar, 'wasn't a single woman but a hundred men."[25]

Most Muslim men appear to have no problem learning from Rabia.

Anecdotes

- "I want to put out the fires of Hell, and burn down the rewards of Paradise. They block the way to God. I do not want to worship from fear of punishment or for the promise of reward, but simply for the love of God."Smith. 2001. page 98.</ref>

- At one occasion she was asked if she hated Satan. Hazrat Rabia replied: "My love to God has so possessed me that no place remains for loving or hating any save Him."[26]

- Once Hazrat Rabia was on her way to Makka, and when half-way there she saw the Ka'ba coming to meet her. She said, "It is the Lord of the house whom I need, what have I to do with the house? I need to meet with Him Who said, 'Who approaches Me by a span's length I will approach him by the length of a cubit.' The Ka'ba which I see has no power over me; what joy does the beauty of the Ka'ba bring to me?" [10]

- Rab'eah was once asked, "did you ever perform any work that, in your opinion, caused God to favor and accept you?" She replied, "Whatever I did, may be counted against me."[27]

Legacy

Her pioneering of love-mysticism in Islam produced a rich legacy. The poetry and philosophy of Farid ad-Din Attar, among that of others, stands on her shoulders. It is primarily from his work that what little biographical information we have has survived. However, lack of details of her life is compensated by the abundance of stories of her piety and total trust in God to provide for her every meal. Her love of God and her confidence in God's mercy was absolute; since God provided for "those who insult Him" her would surely "provide for those who love Him" as well.[28] The high praise that Rabia attracts from Muslim men as well as from Muslim women testifies to the value of her legacy as a guide for others to realize the same intimacy with God that she enjoyed. The fact that details of her life have not survived while her reputation for piety has means that her achievements do not overshadow her devotion to God. Not only did she not teach at a prestigious institution or establish one but exactly where she did teach remains obscure Nonetheless her legacy impacted significantly on religious life and thought.

Notes

- ↑ Nurbakhsh (1990), 25.

- ↑ ʻAṭṭār and Arberry (1966), 39.

- ↑ Nurbakhsh (1990), 32.

- ↑ ʻAṭṭār and Arberry (1966), 40; Smith (2001), 5.

- ↑ Smith (2001), 6.

- ↑ ʻAṭṭār and Arberry (1966), 41.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Smith (2001), 7.

- ↑ ʻAṭṭār and Arberry (1966), 42; Smith (2001), 7.

- ↑ ʻAṭṭār, Davis, and Darbandi (1984), 86.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Nurbakhsh (1990), 33.

- ↑ Attar (2008), 45.

- ↑ El Sakkakini (1982), 47.

- ↑ El Sakkakini (1982), 55.

- ↑ Nurbakhsh (1990), 47.

- ↑ El Sakkakini (1982), 65.

- ↑ D.S. Margoliouth, Mohammedanism (London, UK: Williams and Norgate), 106.

- ↑ ʻAṭṭār and Arberry (1966), 51; Smith (2001), 30.

- ↑ H.A.R. Gibb, Mohammedanism (New York, NY: Oxford university Press, 1970, ISBN 0195002458), 90.

- ↑ Clinton Bennett, In Search of Muhammad (London, UK: Cassell, 1998, ISBN 0304704016), 171.

- ↑ Smith (2001), 123-4.

- ↑ Smith (2001), 12-13.

- ↑ Attar. 2008. page 46.

- ↑ ʻAṭṭār and Arberry. 1966. page 51.

- ↑ ʻAṭṭār and Arberry. 1966. page 40

- ↑ Nūrbakhsh. 1990. page 25.

- ↑ Smith. 2001. page 99.

- ↑ Nurbakhsh. 1990. page 68.

- ↑ ʻAṭṭār and Arberry. 1966. page 49.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- El Sakkakini, Widad. 1982. First among Sufis: the life and thought of Rabia al-Adawiyya, the woman Saint of Basra. London, UK: Octagon Press. ISBN 9780900860454.

- Smith, Margaret. 2001. Muslim women mystics: the life and work of Rábiʻa and other women mystics in Islam. Great Islamic thinkers. Oxford, UK: Oneworld. ISBN 9781851682508.

- Nūrbakhsh, Javād. 1990. Sufi women. London, UK: Khaniqahi-Nimatullahi. ISBN 9780933546424.

- ʻAṭṭār, Farīd al-Dīn, Dick Davis, and Afkham Darbandi. 1984. The conference of the birds. The Penguin classics. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140444346.

- ʻAṭṭār, Farīd al-Dīn, and A.J. Arberry. 1966. 39-51 Rabe'a al-Adawiya. 29-47 Muslim saints and mystics: episodes from the Tadhkirat al-Auliya'. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Nicholson, A R. 2007. The Mystics of Islam. Eastbourne, UK: Gardners Books. ISBN 9780979266546.

External links

All links retrieved December 7, 2022.

- Rabia and the Bliss and Pleasure after the Heaviness of Struggle.

- Ismaili Web - Rabia the Slave.

- Mythinglinks.org—eighth Century Islamic Saint.

- Rabi'a, Al-Hallaj and Ibn 'Arabi.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.