Deism

The definition of the term "deism" is two-fold. Firstly, in the context of religious classification, it refers to a theological philosophy which conceives of God as a detached creator who designed the universe and the laws which govern it, but has little impact upon the day to day workings of the world. In the second sense, historical and modern deism refers to a religious movement which peaked during the eighteenth century. These individuals are of the belief that reason, rather than revelation or tradition, should be the basis of religion. The Deists do not necessarily accept the maxims of deism in the philosophical sense mentioned above, and this movement would now most likely be classified as adhering to a worldview more congruent with theism.

Deism as a Religious Classification

In addition to its designation as a religious movement, Deism can also be used to describe a general philosophy concerning the nature of God and the cosmos. This philosophical Deism was not necessarily an exact replica of the beliefs of the various manifestations of historical deism, however, there is a considerable amount of overlap between the two senses of the term. Philosophical Deism acknowledges belief in creator God, the First Cause who brought the universe into existence. From here, this God is referred to by heavily anthropomorphic terminology, construed as a real person, standing over the world of humanity. For example, God is like the watchmaker; much as the watchmaker fashions the parts and functions of the watch, God similarly puts in place the machinations of the universe, and provides the energy which sets the universe in motion. While God is the source of all motion and matter, Deists believe God's intercession into his creation only occurs occasionally, if it occurs at all. God's role, in the mind of the Deist, is merely to create the universe and the laws which operate it, and afterwards to allow these laws to take their course without His assistance. Humans too, may exist fully independent of their maker after creation, and as such, philosophical deism places emphasis on the freedom of human choice.

In the sphere of morality, God is conceived by the Deists as the supreme authority of the moral world. Just as God laid down the laws governing the physical universe, he sets in place the moral order, as well. In this capacity, he serves as the judge of all moral beings within the cosmos, however, he does not necessarily become involved in the process of handing out judgements. Instead, humans are punished and rewarded as a function of their own observance of these laws. Disobedience to God's laws will result in negative consequences for the moral being, thus God's intervention is not required in the distribution of punishment. It is human reason which replaces this continual advent of God, since human's moral welfare in the Deist philosophy is based upon the accuracy of their knowledge of the laws by which the course of the world is determined, including what constitutes good and what constitutes evil.

Deism Through History

Beginnings

Thinking which could be described as Deistic has existed since antiquity, and can be identified in the works of pre-Socratic philosophers such as Heraclitus. However, the foundations of Deist thought as it is known today were laid by Lord Herbert of Cherbury in his book de veritae, prout distinguir a Revelatione, Veristimilit, Probabili, et a False. This work distinguishes principles of primary character independent of all tradition, whether written or oral. These five primary truths are 1) that God exists, 2) it is the duty of humans to worship him, 3) virtuous practice involves doing him honour, 4) man is under obligation to repent his sins, and 5) that there will be rewards and punishments after death based on earthly deeds. Further, Lord Herbert asserted that human reason was sufficient for purposes of attaining certainty with regard to fundamental religious truths. He also insisted that religion should be deeply involved in practical duties. Deistic writers that that followed Lord Herbert enlarged these themes, particularly the postulation that natural reason should be the establishment for religion.

The independent works of other seventeenth century figures also had a hand in affecting the rise of Deism. Although Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) was generally opposed to the concept of natural religion, he pioneered the movement for religious speculation which had been altogether absent within Christianity before his arrival. Therein, he removed one of the primary obstacles standing in the way of Deism, the intransigence of ecclesiastical authority. Furthermore, the Cambridge Platonists, reacting to the increase influece of anti-rationalist dogmatism among the Puritan divines and the narrowly materialist writings of Hobbes, put forward what they conceived to be a set of rational grounds for Christianity. Eschewing these philosophical pressures, they used Platonism to construe human reason as the paramount receptacle for Divine revelation.

Similar to Hobbes, John Locke (1632-1704) had an unintentional effect on Deistic thought. In his work Reasonableness of Christianity, he delineates the progression of Christian doctrine through history. In doing so he provides some discrimination between the valuable and worthless elements of the Creed, showing particular skepticism toward elements of the biblical texts which involve miracles and revelation; further, he conceived the Christian religion to be a powerful moral philosophy rather than means to invigorate the human will with spirit. Although each of these ideas had been formulated prior to Locke's publication, this was the first instance where they were combined systematically. Locke arrives at the conclusion that religion in form that it currently existed should be modified extensively. Hence, the foundations for the Deist movement had been laid.

It was not until the time of the European Enlightenment with its newfound emphases on rigorous skepticism, deductive logic, and empiricism, that deism came into its own as a subject of philosophical discourse. Deism developed from the expanding influence of scientism upon the European intellectual spectrum. Newtonian physics, the intellectual basis for the scientism of the Enlightenment, propogated the idea that matter behaves in a mathematically predictable manner that can be understood by postulating and identifying laws of nature. Concepts borrowed from the observational methods of science such as objectivity, natural equality, and the prescription to treat like cases similarly were central principles of the Enlightenment, and became the rubric for scrutinizing all domains of life during this time period. Inevitably, these principles came to inform the reinterpretation of religion, as well, which resulted in the synthesis of deism, which compromised these principles with religiosity quite tidily. Furthermore, exasperation as a result of the immense toll centuries of religious warfare had taken upon Europe provided a powerful impetus for placing a more rational framework upon spiritual matters.

Popularity in England

The height of Deist popularity occurred in Britain during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The first explicitly Deistic work was John Toland's Christianity Not Mysterious, which was published in 1696 and drew upon some of Locke's postulations, stressing a process where Truth was inferred from nature rather than revelations directly from the divine. Anything a reader of the scriptures could not comprehend through common sense was to be considered false, in Toland's view. The "mystery" of Christianity, in Toland's understanding, was not to be something incomprehensible, but instead more like a secret which is revealed to the initiated. Toland meticulously perused the Gospels and clarified every part of them which seemed contrary to reason. From here he refigured the events of the Gospels into terms which allowed them to be reconciled with rational thought. Reason, Toland asserted, was to be of primary importance not only in everyday life, but in all matters religious, as well. Furthermore, Toland undermined the credibility of early Christian literature as a whole, suggesting that they were, for the most part, works of superstition.

Shortly after in 1713, Anthony Collins published Discourse of Freethinking occassioned by the Rise and Growth of a sect Called Freethinkers. Collins' work went beyond Toland's in attempting to justify the claim that rational inquiry made for virtually limitless freedom for human beings when compared to moral and religious ruminations. Collins ascertained that the Deistic argument rested upon a decision to place a focus on individual liberty in the pursuit of moral investigation, as well as a focus on the individual capacity to discover moral truth. Collins argued that all the great moral pedagouges such as the prophets, Paul, and Jesus Himself taught their disciples by appealing to reason, rather than fear. In contrast, the Church and the State had cultivated fear through superstitious beliefs in order to inspire humans to behave morally, and in the process had created what Toland viewed to be moral corruption. His prescription for religious reform was to excise such fear-inducing superstitions from religious teaching, and to concentrate of the development of morality through rationality in each individual. Moreover, in a later work, Discourse of the Grounds and Reason of Christian Religion, Collins turned the focus to the consideration of whether or not prophecy and miracle are credible phenomena. Specifically, this debate centered around the notion that the correspondence of Old Testament prophecy and New Testament events were adquate proof of Christianity's truth, an idea which had been widely accepted up until that time. Collins challenged this notion, as he questioned the authenticity and accuracy of events such as those in the Gospel which were supposedly dictated by New Testament writers such as the Apostles. If the miracles reported by these authors were to remain in religious discourse, Collins suggested they be reinterpreted as allegory or metaphor to propound the more reasonable contributions of Christ and other religious figures. Collins perpetuated suspicions toward the veracity of biblical documents, and provided further momentum for biblical criticism.

In 1730 Matthew Tindal published Christianity as Old as the Creator, a book which marked what was the culmination of all Deist thought. Tindal further shaped the Deist arguments developed by the thinkers who preceded him, though he managed to synthesize the various strands together and present them in more intelligible langauge than his predecessors had. He further repudiated the mysterious aspects of religion and promoted a general distrust toward religious authority. The ultimate value of religion, he contended, was to aid humans in fashioning their own personal beliefs and to cultivate their moral nature, rather than encouraging them to depend on revelation. He held that in the context of their moral faculties, all humans were equal in the eyes of God at all times. Further, through the gift of reason, humans held the ability to comprehend the consequences of their actions without the continual assistance of God. For Tindal, human duties are evident through the the reason behind things and their relationships with one another. It is upon these natural foundations that religions is constructed. Religion, in Tindal's view, was quite simply a law of nature adapted to accomodate the given circumstances of humankind; that is, religion was seen as what naturally arises from considerations of god. It was in such natural relations and very little else that religious edifices were to be constructed. Tindal held that no command communicated by revelation could be superior to the natural workings of nature, because no command was to be seen as obligatory unless the reasonableness of it was blatantly evident. Corollary with this point, placing anything in religion which is not demonstrable by reason Tindal considered to be an insult to the faculties of human beings and ultimately the honour of God.

Popularity Abroad

Deism also found even more welcoming environments outside of England in the Nineteenth century and beyond. French Enlightenment thinkers such as Voltaire and Rousseau found the ideas particularly appealing and introduced some new elements of their own. Voltaire used Deism as a vehicle for the expressing resentment against the social repression perpetuated by the Catholic Church in France. Of course, the internal passions of the French were already at a peak due to the impending revolution, and Deism fed upon this, becoming identified as an anti-ecclesiastical movement. Rather than transforming theology of the Church as the English Deists had, the French advocated an eschewal of theology altogether. In place of the Catholic Church, they suggested a non-dogmatic religion with Deist ideals be inserted. This attempt eventually failed, as the French variation of Deism gradually evolved into to a form of materialism devoid of any large scale religiosity. Rousseau made similar attempts to instill Deism within French life, but also had little success.

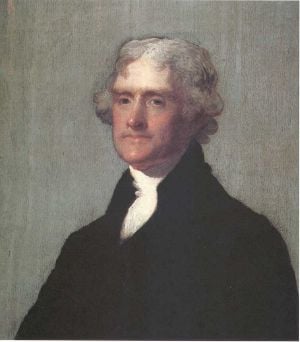

Since America was supposedly championed on the ideals of equality and reason, it is not surprising that numerous founding fathers of the nation such as Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin and George Washington identified themselves as deists. In fact, the first six presidents of the United States, as well as four later ones had strong deistic beliefs. Jefferson even attempted to produce his own variation of biblical scripture with the publication of the so-called Jefferson Bible, also known as The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth. Jefferson composed this volume by removing sections of the New Testament containing supernatural aspects. Also, he excised portions which he interpreted to be misinterpretations or additions that had been made by the writers of the Gospels. What was left, supposedly, was a completely reasonable version of the doctrine of Jesus, featuring only those parts conceivable to rationalistic Deist reader.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the newly developing land of America was dominated by Christianity. Some held the Christian masses in contempt, perceiving their majority as a threat to the Enlightenment ideals of equality and rationality America was built upon. Many of these dissatisfied inviduals sought recourse in Deist ideals; hence, the popularity of Deist thought, which was by this time subsiding in England, was recapitulated on American soil. In 1790, Elihu Palmer, a one-time Baptist minister, launched a nation-wide crusade for Deism. By the turn of the century, Deism had grown in popularity and started to become more accepted among the populace of mainstream America, rivalling Christianity. This caused a vituperative backlash from the Christian establishment, which only served to pique the interest of some congregation members who promptly jumped ship to join the Deists. Well into the nineteenth century, Deism continued to flourish in America.

Decline in popularity

Several factors contributed to a general decline in the popularity of deism, including:

- the writings of David Hume (and later, Charles Darwin) increased doubt about the first cause argument and the argument from design

- several Christian Great Awakenings in the USA, especially those that taught a more personal relationship with a deity, and that prayer could alter events

- loss of confidence that reason and rationalism could solve all problems

- criticisms of excesses of the French Revolution

- criticisms that deism was not significantly distinct from pantheism, and then that pantheism was not significantly different from atheism

- criticisms that freethought would lead inevitably to atheism

- frustration with the determinism implicit in "This is the best of all possible worlds."

- rise of Unitarianism, which adopted many of its ideas

- it remained a personal philosophy and never became an organized movement

- an anti-deist and anti-reason campaign by some Christian clergymen to vilify and equate deism with atheism in public opinion

Current status

Newtonian physics, when linearized and simplified, is considered deterministic, and so deism based on that, for many, left little room for hope. Of some relevance in response to this are newer theories in physics, most notably quantum mechanics, which has both a non-deterministic interpretation (the Copenhagen interpretation), and deterministic interpretations (the transactional interpretation and many-worlds interpretation). Some modern revivals of deism resemble pantheism and panentheism. However, some Unitarian Universalists are bringing deism back in order to counter Fundamentalism.

Contributions of Deism

See also

- Agnosticism

- Atheism

- Cosmological argument

- Cosmotheism

- Evolutionary Creationism

- Freethought

- Ignosticism

- List of deists

- List of U.S. Presidential religious affiliations

- Panendeism

- Panentheism

- Pantheism

- Philosophical theism

- Polydeism

- Transcendentalism

- Transtheism

External links

External informational links

- DEISTPEDIA: The Deist Encyclopedia

- DEISM: The Union of Reason and Spirituality

- Deism and Reason

- Of the Religion of Deism Compared with the Christian Religion by Thomas Paine

- The Age of Reason by Thomas Paine

- Definition of deism from The Dictionary of the History of Ideas at the University of Virginia

- English Deism - Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- French Deism - Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- On some links between Deism and Freemasonry - Warning: agenda driven article, but it does make some connections

- religious tolerance.org article on Deism

External organization links

- Deism and Reason

- Positive Deism

- Dynamic Deism

- PONDER

- Deist.info

- World Union of Deists

- Aldeism

- American/ Unitarian Conference

- Temple of Reason

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Joyce, Gilbert Cunningham. “Deism” Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. James Hastings, ed. Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1910. 334-345.

- Walters, Kerry S. Rational Infidels: The American Deists. Durango, CAL: Longwood Academic, 1992.

- Toland, John. John Toland's Christianity Not Mysterious: Text, Associated Works and Critical Essays. Alan Harrison, Richard Kearney, Philip McGuinness, Eds. Dublin: Lilliput Press, 1998.