Deism

Historical and modern deism is defined by the view that reason, rather than revelation or tradition, should be the basis of belief in God. Deists reject both organized and revealed religion and maintain that reason is the essential element in all knowledge. For a "rational basis for religion" they refer to the cosmological argument (first cause argument), the teleological argument (argument from design), and other aspects of what was called natural religion. Deism has become identified with the classical belief that God created but does not intervene in the world, though this is not a necessary component of deism.

Beginnings

Thinking which could be described as Deistic has existed since antiquity, and can be identified in the works of pre-Socratic philosophers such as Heraclitus. However, the foundations of Deist thought as it is known today were laid by Lord Herbert of Cherbury in his book de veritae, prout distinguir a Revelatione, Veristimilit, Probabili, et a False. This work distinguishes principles of primary character independent of all tradition, whether written or oral. These five primary truths are 1) that God exists, 2) it is the duty of humans to worship him, 3) virtuous practice involves doing him honour, 4) man is under obligation to repent his sins, and 5) that there will be rewards and punishments after death based on earthly deeds. Further, Lord Herbert asserted that human reason was sufficient for purposes of attaining certainty with regard to fundamental religious truths. He also insisted that religion should be deeply involved in practical duties. Deistic writers that that followed Lord Herbert enlarged these themes, particularly the postulation that natural reason should be the establishment for religion.

18th century popularity

It was not until the modern era, during the European Enlightenment and Scientific Revolution, with their respective emphases on rigorous skepticism, deductive logic, and empiricism (experience/induction), that deism came into its own as a subject of philosophical discourse, particularly in France (Descartes, the Philosophes), Germany (Kant†, Leibniz), Great Britain (Hobbes, Hume‡), and the United States (Paine, Franklin).

Deism developed from the expanding influence of scientism in Europe and European colonial intellectual life. Newtonian physics, the intellectual basis and the aesthetic model for Enlightenment scientism, spread the idea that matter behaves in a mathematically predictable manner that can be understood by postulating laws of nature. Objectivity, natural equality, the prescription to treat like cases similarly are central principles of the Enlightenment mentality, ideas borrowed from Newton's observational/experimental method and put to use in all domains the Enlightenment mind scrutinized; these principles informed the development of the philosophy of deism. Exasperation with the costs of centuries of European religious warfare was a powerful recommendation for the new, objective frame for spiritual matters, a perspective the most notable minds of the time found appealing.

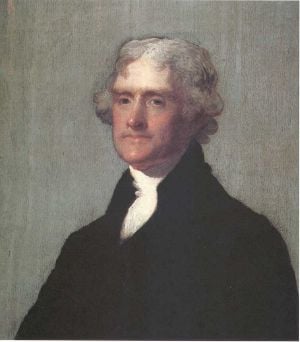

Deism was championed by Enlightenment thinkers such as Voltaire and some of the Founding Fathers of the United States. Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin and George Washington are among the most well-known of the American founding deists. Thomas Paine published The Age of Reason, a treatise that popularized deism throughout America and Europe. Paine wrote that deism represented the application of reason to religion, finally settling problems that formerly were thought to be permanently controversial. Deists hoped to also settle religious questions permanently and scientifically by reason alone, without revelation. The first six and four later presidents of the United States had strong deistic or allied beliefs.

Decline in popularity

Several factors contributed to a general decline in the popularity of deism, including:

- the writings of David Hume (and later, Charles Darwin) increased doubt about the first cause argument and the argument from design

- several Christian Great Awakenings in the USA, especially those that taught a more personal relationship with a deity, and that prayer could alter events

- loss of confidence that reason and rationalism could solve all problems

- criticisms of excesses of the French Revolution

- criticisms that deism was not significantly distinct from pantheism, and then that pantheism was not significantly different from atheism

- criticisms that freethought would lead inevitably to atheism

- frustration with the determinism implicit in "This is the best of all possible worlds."

- rise of Unitarianism, which adopted many of its ideas

- it remained a personal philosophy and never became an organized movement

- an anti-deist and anti-reason campaign by some Christian clergymen to vilify and equate deism with atheism in public opinion

Current status

Newtonian physics, when linearized and simplified, is considered deterministic, and so deism based on that, for many, left little room for hope. Of some relevance in response to this are newer theories in physics, most notably quantum mechanics, which has both a non-deterministic interpretation (the Copenhagen interpretation), and deterministic interpretations (the transactional interpretation and many-worlds interpretation). Some modern revivals of deism resemble pantheism and panentheism. However, some Unitarian Universalists are bringing deism back in order to counter Fundamentalism.

See also

- Agnosticism

- Atheism

- Cosmological argument

- Cosmotheism

- Evolutionary Creationism

- Freethought

- Ignosticism

- List of deists

- List of U.S. Presidential religious affiliations

- Panendeism

- Panentheism

- Pantheism

- Philosophical theism

- Polydeism

- Transcendentalism

- Transtheism

External links

External informational links

- DEISTPEDIA: The Deist Encyclopedia

- DEISM: The Union of Reason and Spirituality

- Deism and Reason

- Of the Religion of Deism Compared with the Christian Religion by Thomas Paine

- The Age of Reason by Thomas Paine

- Definition of deism from The Dictionary of the History of Ideas at the University of Virginia

- English Deism - Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- French Deism - Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- On some links between Deism and Freemasonry - Warning: agenda driven article, but it does make some connections

- religious tolerance.org article on Deism

External organization links

- Deism and Reason

- Positive Deism

- Dynamic Deism

- PONDER

- Deist.info

- World Union of Deists

- Aldeism

- American/ Unitarian Conference

- Temple of Reason

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Joyce, Gilbert Cunningham. “Deism” Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. James Hastings, ed. Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1910. 334-335.