Difference between revisions of "Classical economics" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

[[Category:Economics]] | [[Category:Economics]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | '''Classical economics''' is widely regarded as the first modern school of [[history of economic thought|economic thought]]. Its major developers include [[Adam Smith]], [[David Ricardo]], [[Thomas Malthus]] and [[John Stuart Mill]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | Classical | + | The term 'Classical' refers to work done by a group of economists in the 18th and 19th centuries. Much of this work was developing theories about the way markets and market economies work. Much of this work has subsequently been updated by modern economists and they are generally termed neo-classical economists, the word neo meaning 'new'. |

| − | == | + | ==Short history of classical economics== |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Adam Smith, J.B. Say, Robert Malthus and David Richardo=== | |

| − | + | In the year 1776, [[David Hume]] died while [[Jacques Turgot]] and [[Marquis de Condorcet]] left their government posts. But, in that same year, the intellectual revolution they had contributed to, the Enlightenment, began to bear its principal fruit. It was a year of grand treatises. [[Adam Smith]] published his ''Wealth of Nations'', the [[Abbé de Condillac]] his ''Commerce et le Gouvernement'',[[ Jeremy Bentham]] his ''Fragments on Government'' and [[Tom Paine]] his ''Common Sense''. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The Victorian period of rapid expansion worldwide seemed to cheer the Classical economists up quite a little and they became a more optimistic, but still maintained their total faith in the role of markets. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | They believed that the government should not intervene to try to correct this as it would only make things worse and so the only way to encourage growth was to allow free trade and free markets. | |

| + | |||

| + | This approach is known as a '''''laissez-faire''''' approach. Essentially this approach places total reliance on markets, and anything that prevent markets clearing properly should be done away with. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Much of Adam Smith's early work was on this theme, and he introduced the notion of an invisible hand that guided economic activity and led to the optimum equilibrium. Many people see him as the founding father of modern economics. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Written during the Enlightenment, the central messages of Adam Smith's ''Wealth of Nations'' (1776) — laissez-faire, the virtues of specialization, free trade and competition, etc. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In the struggle for apostolic succession, three names emerged as strong contenders: | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *[[Jean-Baptiste Say]], | ||

| + | |||

| + | *[[Robert Malthus]] and | ||

| + | |||

| + | *[[David Ricardo]]. | ||

| − | == | + | They all had different visions for political economy after Smith. Say (1803) wanted to take it back towards the French-Italian demand-and-supply tradition. Malthus (1798, 1820) wanted to add a whole new emphasis, away from the obsessive intricacies of "value" and towards a more macroeconomic (and "dynamic") perspective. Ricardo (1817) wanted to do Smith all over again, but to do it properly this time. |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Out of all three, David Ricardo turned out to be the most successful and influential. With his 1817 treatise, Ricardo took economics to an unprecedented degree of theoretical sophistication. Ricardo's theory, the most clearly and consistently formalized of them all, became the ''Classical system''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Classical Theory== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Classical theories revolved mainly around the role of markets in the economy. If markets worked freely and nothing prevented their rapid clearing then the economy would prosper. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Any imperfections in the market that prevented this process should be dealt with by government. The main roles of government are therefore to ensure the free workings of markets using 'supply-side policies' and to ensure a balanced budget. The main theories used to justify this view were: | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *'''Free market theory'''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *'''Say's Law'''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *'''Quantity Theory of Money'''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ===Free market theory=== | ||

| + | The Classical economists assumed that if the economy was left to itself, then it would tend to full employment equilibrium. This would happen if the labour market worked properly. If there was any unemployment, then the following would happen: | ||

| + | |||

| + | unemployment increased demand for labour fall in wages equilibrium restored at ( a surplus of labour) full employment | ||

| + | |||

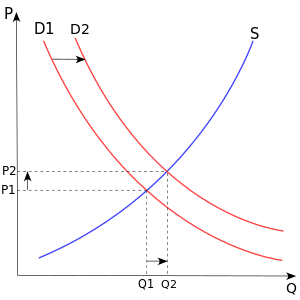

| + | As the Graph below illustrates, it is argued that there is an inverse relationship between the wage rate ( i.e. price of labour ) , depicted on the vertical “price” axis P, and the quantity of labor demanded, which is depicted ( as quantity of any other goods ) on the horizontal “quantity axis Q. There is also a “supply”( of labour ) curve S in this graph. This negative relationship between the wage and the quantity of labor demanded is the result of two effects: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Supply-and-demand.svg|thumb|right|An example of a demand curve]] | ||

| + | In [[economics]], the '''demand curve''' can be defined as the [[graph]] depicting the relationship between the price of a certain [[commodity]], and the amount of it that consumers are willing and able to purchase at that given price (see [[demand]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | * A substitution effect. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Suppose that the wage rate increases in the “demand” curve from D1to D2. The substitution effect of the wage increase involves the substitution of other resources (such as capital, energy, materials, and other categories of labor) for the category of labor that has become more expensive. As the wage rate rises from P1 to P2 , the substitution effect results in a reduction in the quantity of labor demanded; from Q2 ro Q1. Note that the “supply” of labour S is constant all through the process. | ||

| + | |||

| + | An equilibrium occurs in a labor market at the combination of wages and employment at which market demand and supply intersect ( as illustrated in the Diagram above. ) . | ||

| + | If the wage rate is above the equilibrium, the quantity of labor supplied exceeds the quantity demanded and a surplus occurs. In this case, the existence of unemployed workers will be expected to result in downward pressure on the wage rate until an equilibrium is restored. | ||

| + | If the wage rate is below the equilibrium, a labor shortage will occur. Competition among firms for workers is expected to result in increases in the wage until an equilibrium occurs. | ||

| + | *A scale effect. | ||

| + | The scale effect resulting from a wage increase is a bit more complex. As the wage rate rises, the scale effect involves the following chain of effects: | ||

| + | *(a) higher wages result in higher average and marginal costs of production, | ||

| + | *(b) higher average and marginal and average costs result in an increase in the equilibrium price of the product, | ||

| + | *(c) as the price of the product rises, the equilibrium quantity of the product demanded declines (a reduction in the "scale" of production), and | ||

| + | *(d) the reduction in output results in a reduction in the quantity of all inputs used to produce this product (including this category of labor). | ||

| + | ===Say’s Law: Supply-side policies === | ||

| + | So, Classical economists are of the view that the economy is self-adjusting. We can therefore sum up their policy recommendations in a variation on a well-known phrase: | ||

| + | “…Don't just do something, sit there!’ | ||

| + | Of course, taking this too literally would be unfair on Classical economists, but it would be true to say that because the economy tends to full-employment, there is no need to actively intervene in the economy. In fact intervention may simply be destabilising and inflationary. The key to long-term stable growth is therefore: | ||

| + | *Ensure free markets with no imperfections ( through supply-side policies ) | ||

| + | *Control the growth of the money supply to ensure low inflation | ||

| + | For Say, the foundation of value is utility or the capacity of a good or service to satisfy some human desire. Those desires and the preferences, expectations, and customs that lie behind them must be taken as givens, as data, by the analyst. The task is to reason from those data. Say is most emphatic in denying the claims of Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and others that the basis for value is labor, or "…productive agency……" ( Say, 1803, p.348 ) | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Nowhere is Say's radicalism more evident than in his critique of government intervention into the economy. Most succinctly stated, he declares that self-interest and the search for profits will push entrepreneurs toward satisfying consumer demand. "…..the nature of the products is always regulated by the wants of society," therefore "legislative interference is superfluous altogether…..."( ibid., p.144 ) | ||

| + | |||

| + | It was also in the Treatise ( Say, 1803 ) that Say outlined his famous "Law of Markets". Roughly stated, Say's Law claims that total demand in an economy cannot exceed or fall below total supply in that economy or as [[James Mill]] was to restate it, "…supply creates its own demand……" | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Say's language, "….products are paid for with products…." ( ibid., p.153) or "….a glut can take place only when there are too many means of production applied to one kind of product and not enough to another….."( ibid., p.178-9.). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Using supply-side policies can be seen in the above Diagram when we assume only one price level, say, P1 and we increase the level of output from Q1 to Q2, while the price level P1 has remained stable. Supply-side policies as we have said are ones that reduce market imperfections. They may include: | ||

| + | *Improving education & training to make the work-force more occupationally mobile | ||

| + | *Reducing the level of benefits to increase the incentive for people to work | ||

| + | *Reducing taxation to encourage enterprise and encourage hard work | ||

| + | *Policies to make people more geographically mobile (scrapping rent controls, simplifying house buying to speed it up, ......) | ||

| + | *Reducing the power of trade unions to allow wages to be more flexible | ||

| + | *Getting rid of any capital controls | ||

| + | *Removing unnecessary regulations | ||

| + | ===Quantity theory of money=== | ||

| + | The other area that Classical economists felt was important was to control monetary growth. In this way as predicted by the Quantity Theory of Money) they would be able to maintain low inflation. | ||

| + | The Quantity Theory of Money ( QTM ) states that there is a direct relationship between the quantity of money in an economy and the level of prices of goods and services sold. According to QTM, if the amount of money in an economy doubles, price levels also double, causing inflation (the percentage rate at which the level of prices is rising in an economy). The consumer therefore pays twice as much for the same amount of the good or service. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In its simplest form, the theory is expressed as | ||

| + | |||

| + | * MV = PT (the Fisher Equation). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Each variable denotes the following: | ||

| + | |||

| + | M = Money Supply | ||

| + | V = Velocity of Circulation (the number of times money changes hands) | ||

| + | P = Average Price Level | ||

| + | T = Volume of Transactions of Goods and Services | ||

| + | |||

| + | The original theory was considered orthodox among 17th century classical economists and was overhauled by 20th-century economists Irving Fisher, who formulated the above equation, and Milton Friedman ( Friedman, 1987 ) . It is built on the principle of ‘equation of exchange’: | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Amount of Money x Velocity of Circulation = Total Spending | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Another way to understand this theory is to recognize that money is like any other commodity: increases in its supply decrease marginal value (the buying capacity of one unit of currency). So an increase in money supply causes prices to rise (inflation) as they compensate for the decrease in money’s marginal value. | ||

| + | Policies might include: | ||

| + | *Open-market operations. | ||

| + | *Funding. | ||

| + | *Monetary-base control. | ||

| + | *Interest rate control. | ||

| + | ==Classical Economics vs. The Exploitation Theory== | ||

| + | “The exploitation theory” is one of the most powerful factors that have been operating to lead the world down The Road to Serfdom —as the title of Prof. Hayek's book describes the trend toward socialism ( Hayek, 1944. ) Indeed, the influence of the exploitation theory goes far beyond the direct and obvious support it gives to socialism. It has contributed to the triumph of socialism in more subtle ways, as well. It played a major, perhaps the decisive, role in the overthrow of British classical economics. | ||

| + | Along with "the labor theory of value" and the "iron law of wages," they discarded such further features of classical political economy as the wages fund doctrine and its corollary that savings and capital are the source of almost all spending in the economic system. Two generations later, the abandonment of the classical doctrines on saving made possible the acceptance of Keynesianism and the policy of inflation, deficits, and ever expanding government spending. | ||

| + | Similarly , the abandonment of the classical doctrine that cost of production, rather than supply and demand, is the direct (if not the ultimate) determinant of the prices of most manufactured or processed goods led, with just about the same time lag, to the promulgation of the doctrines of "pure and perfect competition," "oligopoly," "monopolistic competition," and "administered prices," with their implicit call for a policy of radical antitrust or outright nationalizations to "curb the abuses of big business." Thus, along these two further paths, the influence of the exploitation theory has served to advance the cause of socialism. | ||

| + | ===Smith and Marx vs. Bohm-Baverk=== | ||

| + | There are three aspects of classical economics which contribute to the exploitation theory. The two best known are: | ||

| + | *The labor theory of value and | ||

| + | *the iron law of wages. | ||

| + | Somewhat less prominent, but no less important, is the conceptual framework within which the exploitation theory is advanced. This framework is the belief that: | ||

| + | *Wages are the original and primary form of income, from which profits and all other non-wage incomes emerge as a deduction with the coming of capitalism and businessmen and capitalists. | ||

| + | It is on the basis of these beliefs that Adam Smith opens his chapter on wages in The Wealth of Nations with the words: | ||

| + | “…..The produce of labour constitutes the natural recompense or wages of labour. In that original state of things, which precedes both the appropriation of land and the accumulation of stock, the whole produce of labour belongs to the labourer. He has neither landlord nor master to share with him…..” | ||

| + | |||

| + | In these, and other passages, Smith clearly advances the primacy of wages doctrine. That is, the doctrine that in a pre-capitalist economy—the "early and rude state of society"—in which workers simply produce and sell commodities and do not buy in order to sell, the incomes the workers receive are wages. | ||

| + | “….Wages are the original income…”, according to Smith. “…..All income in the pre-capitalist society is supposed to be wages, and no income is supposed to be profit….,” according to Smith, “…..because workers are the only recipients of income….” | ||

| + | At the same time, of course, Smith advances the corollary doctrine that profit emerges only with the coming of capitalism and is a deduction from what is naturally and, by implication, rightfully wages. | ||

| + | These doctrines, appears to constitute the conceptual framework of the exploitation theory. They are the starting point for Marx ( Reisman 1985. ) | ||

| + | Profits, then, according to both Smith and Marx, come into existence only with capitalism, and are a deduction from what naturally and rightfully belongs to the wage earners. | ||

| + | This is not yet the exploitation theory itself, only the conceptual framework of the exploitation theory. It is a framework broad enough to include Marx, the leading proponent of the exploitation theory, and Böhm-Bawerk, its leading critic. | ||

| + | Within this framework, Marx applies the labor theory of value and the iron law of wages, and arrives at the exploitation theory. Within this same framework, Böhm-Bawerk applies the discounting approach, and arrives at a critique of the exploitation theory ( Bohm-Bawerk, 1959. ) Both men call upon their respective doctrines to explain what makes possible the alleged deduction of profits from wages and what determines the size of this deduction. | ||

| + | For classical economics implies that it is false to claim that wages are the original form of income and that profits are a deduction from them. This becomes apparent, as soon as we define our terms along classical lines: | ||

| + | *"Profit" is the excess of receipts from the sale of products over the money costs of producing them—over, it must be repeated, the money costs of producing them. | ||

| + | *A "capitalist" is one who buys in order subsequently to sell for a profit. | ||

| + | *"Wages" are money paid in exchange for the performance of labor—not for the products of labor, but for the performance of labor itself. | ||

| + | On the basis of these definitions it follows that, if there are merely workers producing and selling their products, the money which they receive in the sale of their products is not wages. | ||

| + | "…Demand for commodities….," to quote John Stuart Mill, "….is not demand for labour….. in buying commodities, one does not pay wages, and in selling commodities, one does not receive wages. …..”( Mill, 1976. ) | ||

| + | ===Reevaluation of wages=== | ||

| + | Hence it is possible that, both, Smith and Marx are wrong. Wages are not the primary form of income in production. Profits are. In order for wages to exist in production, it is first necessary that there be capitalists. The emergence of capitalists does not bring into existence the phenomenon of profit. Profit exists prior to their emergence. The emergence of capitalists brings into existence the phenomena of wages and money costs of production. | ||

| + | Accordingly, the profits which exist in a capitalist society are not a deduction from what was originally wages. On the contrary, the wages and the other money costs are a deduction from sales receipts—from what was originally all profit. The effect of capitalism is to create wages and to reduce profits relative to sales receipts. The more economically capitalistic the economy—the more the buying in order to sell relative to the sales receipts, the higher are wages and the lower are profits relative to sales receipts. | ||

| + | Thus, capitalists do not impoverish wage earners, but make it possible for people to be wage earners. For they are responsible not for the phenomenon of profits, but for the phenomenon of wages. They are responsible for the very existence of wages in the production of products for sale. Without capitalists, the only way in which one could survive would be by means of producing and selling one's own products, namely, as a profit earner. | ||

| + | But to produce and sell one's own products, one would have to own one's own land, and produce or have inherited one's own tools and materials. Relatively few people could survive in this way. The existence of capitalists makes it possible for people to live by selling their labor rather than attempting to sell the products of their labor. Thus, between wage earners and capitalists there is in fact the closest possible harmony of interests, for capitalists create wages and the ability of people to survive and prosper as wage earners. And if wage earners want a larger relative share for wages and a smaller relative share for profits, they should want a higher economic degree of capitalism—they should want more and bigger capitalists. | ||

| + | ====Wages determination solely by supply & demand==== | ||

| + | Once it is recognized that money wages are determined strictly by supply and demand, then it becomes clear that the wage earner's presumable willingness to work for a subsistence wage rather than die of starvation, and the capitalist's preference, other things equal, to pay lower wages rather than higher wages, are both irrelevant to the wage the worker must actually be paid. That wage is determined by the demand for and supply of labor. It can fall no lower than corresponds to the point of full employment. If it drops below that point, a labor shortage is created, which makes it to the self-interest of employers able and willing to pay a higher wage to bid wages up, so that they do not lose employees to other employers not able or willing to pay as much. | ||

| + | In addition, wage rates themselves and prices of various materials determined by supply and demand are further factors entering into the determination of prices even in the domain where quantity of labor is relevant ( Mill, 1976.) And, as previously indicated, of course, determination of price by cost is never an ultimate determination, for the prices that constitute the costs are themselves determined by supply and demand and reflect the utility of marginal products, as Böhm-Bawerk explained ( Bohm-Bawerk, vol. 2.) And, to be sure, there are product prices which have no connection whatever to quantity of labor or cost of production in any form, but are determined exclusively by supply and demand, as Ricardo pointed out ( Ricardo, 1821, Chap.I,Sec.I. ) | ||

| + | But also, it should be made clear, which the classical economists never succeeded in doing, that the quantity of labor as a determinant of prices is strictly confined to the category of reproducible products. Major categories of prices are in no way determined by it—above all, wage rates. Such prices are determined by supply and demand—by marginal utility, including the utility of marginal products. Nor are wages connected even indirectly with the "cost of production of labor." | ||

| + | Of course, even within the domain of reproducible products, quantity of labor is by no means the only determinant of price. As Ricardo himself explained in Sections IV-VI of his chapter on value, the period of time for which profits must compound on wages before the ultimate, final product is sold to consumers is a second major determinant of prices ( Ricardo, op. cit.,Chap. I. ) | ||

| + | ===Reevaluation of capitalists vs. workers coexistence=== | ||

| + | Historical confirmation of possibility of such a re-evaluation of can be found in Prof. Hayek's Introduction to Capitalism and the Historians. There we find such statements as: "…..The actual history of the connection between capitalism and the rise of the proletariat is almost the exact opposite of that which these theories of the expropriation of the masses suggest……."( Hayek, 1954. ) | ||

| + | And: "…….The proletariat which capitalism can be said to have 'created' was thus not a proportion of the population which would have existed without it and which it degraded to a lower level; it was an additional population which was enabled to grow up by the new opportunities for employment which capitalism provided……."( ibid., 1954. ) | ||

| + | But also, guiding and directing intelligence, not muscular exertion, is the essential characteristic of human labor. As von Mises says, "…..What produces the product are not toil and trouble in themselves, but the fact that the toiling is guided by reason……."( Mises, 1956. ) Guiding and directing intelligence in production is, of course, supplied by businessmen and capitalists on a higher level than by wage earners—a circumstance reinforcing the primary productive status of profits and profit earners over wages and wage earners. | ||

| + | The precise nature of the work of businessmen and capitalists needs to be explained. In essence, it is to raise the productivity, and thus the real wages, of manual labor by means of creating, coordinating, and improving the efficiency of the division of labor. Several major functions could be easily acknowledged: | ||

| + | * (1) Businessmen and capitalists create division of labor in founding and organizing business firms and in providing capital. | ||

| + | * (2) Businessmen and capitalists coordinate the division of labor in seeking to avoid losses and to earn higher rates of return on their capital in preference to lower rates of return. They try to avoid over-expanding any industry relative to other industries and, at the same time, to be sure that any industry that is insufficiently expanded relative to other industries is further expanded. This is a major aspect of the significance of the principle, so well developed by the classical economists, that there is a tendency toward a uniform rate of profit on capital invested in all branches of industry ( Smith, Ricardo, Riesman op. cit. ) | ||

| + | * (3) Businessmen and capitalists continuously improve the efficiency of production as the result both of their competitive quest for exceptional rates of profit and their saving and investment for the purpose of accumulating personal fortunes. The only way to earn an exceptional rate of profit where the legal freedom of competition prevails is by being an innovator in the production of better products or equally good but less expensive products. The exceptional profits from any given innovation then disappear as competitors begin to adopt it and make it into the normal standard of an industry. This requires that one introduce repeated innovations as the condition of continuing to earn an exceptional rate of profit. In this way, the entire benefit of every innovation tends to be passed forward to the consumers in the form of better products and lower prices, with exceptional profits being entirely transitory in the case of each particular innovation and a permanent phenomenon only insofar as improvement is continuous ( Reisman, 1996, p. 179. ) | ||

| + | ====A Reinterpretation of Labor's Right to the Whole Produce==== | ||

| + | The fact that profits are an income attributable to the labor of businessmen and capitalists, and the further fact that their labor represents the provision of guiding and directing intelligence at the highest level in the productive process, suggests a radical reinterpretation of the doctrine of labor's right to the whole produce. Namely, that that right is satisfied when first the full product and then the full value of that product comes into the possession of businessmen and capitalists (which is exactly what occurs, of course, in the everyday operations of a market economy). For they, not the wage earners are the fundamental producers of products. | ||

| + | ===Summary and Conclusion=== | ||

| + | Despite the support which it historically gave to the “exploitation theory”, classical economics provides the basis for turning the exploitation theory upside down. On the basis of Ricardo's concept of profit and J. S. Mill's proposition that "demand for commodities is not demand for labour," it makes it possible to show how profits, not wages, must be regarded as the original and primary form of income, from which other incomes emerge as a deduction. And, further, not only how profits are a labor income (despite their variation with the size of the capital invested and the period of time for which it is invested), but how the labor of businessmen and capitalists has more fundamental responsibility for the production of products than the labor of wage earners, with the result that "labor's right to the whole produce" should mean the right of businessmen and capitalists to the sales receipts—a right which is honored every day, in the normal operations of a capitalist economy. In addition, the classical doctrines of supply and demand, the wage fund, the distinction between value and riches, and even the labor theory of value (appropriately modified along lines suggested by Ricardo and J. S. Mill and incorporating the advances in price theory made by Böhm-Bawerk) make possible an explanation of real wages based on the productivity of labor, which it is the economic function of businessmen and capitalists steadily to increase. Finally, it can be shown how socialism, with its universal state monopoly on employment and supply, is the economic system to which the exploitation theory actually applies. | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==References== | |

| + | *Böhm-Bawerk, E. von.,Capital and Interest, op. cit., Vol. I, pp. 263-71; Vol. II, pp. 259-89, Libertarian Press, South Holland, Illinois 1959 | ||

| + | *Fisher, I., ''The Purchasing Power of Money''1911 | ||

| + | *Friedman, M., “Quantity theory of money”, A Dictionary of Economics, The New Palgrave:, v. 4, 1987, p. 15. | ||

| + | *Hayek, F. A. ,The Road to Serfdom, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1944 | ||

| + | *Hayek, F. A. editor, Capitalism and the Historians, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1954, pp. 15f. | ||

| + | *Hollander, J.,"The Development of the Theory of Money From Adam Smith to David Ricardo", Quarterly J. of Economics, 1910 | ||

| + | *Laidler, D. The Golden Age of the Quantity Theory, Princeton | ||

| + | University Press. Princeton, NJ, 1991 | ||

| + | *Mill, John S.,Principles of Political Economy, Bk. III, Chaps. III – VI, Ashley Edition (reprint, Fairfield, New Jersey) Augustus M. Kelley 1976 | ||

| + | *Mises, Ludwig von, Human Action, Third Revised Edition, Henry Regnery Company, Chicago, 1966, p. 142. | ||

| + | *Newcomb, S. ''Principles of Political Economy'’, Harper, NY, 1885 | ||

| + | *Reisman,G., “Classical Economics vs. The Exploitation Theory” in:The Political Economy of Freedom Essays in Honor of F. A. Hayek, Edited by Kurt R. Leube and Albert H. Zlabinger Philosophia Verlag, München and Wien, The International Carl Menger Library, 1985*Reisman, G., Capitalism: A Treatise on Economics, Jameson Books, Ottawa, IL, 1996, pp. 200-201, 206-209, 414-441 | ||

| + | *Ricardo, David, Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, Third Edition, London 1821, Chap. IV | ||

| − | + | *Say, Jean-Baptiste, [ orig.1803], A Treatise on Political Economy: or the Production, Distribution and Consumption of Wealth, (translated by C.R. Prinsep and Clement C. Biddle) Augustus M. Kelley, New York 1971 | |

| + | *Smith, Adam, The Wealth of Nations, Cannan Edition, Bk. I, Chap. VIII. | ||

| + | *Smith, Adam op. cit.,Bk. I, Chap. X, Pt. I; Ricardo, David, Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, Third Edition, (London: 1821), Chap. IV. See also Reisman, Capitalism, pp. 172-180. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Credits|Classical_economics|109613401|}} | {{Credits|Classical_economics|109613401|}} | ||

Revision as of 18:57, 23 October 2007

Classical economics is widely regarded as the first modern school of economic thought. Its major developers include Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Thomas Malthus and John Stuart Mill.

The term 'Classical' refers to work done by a group of economists in the 18th and 19th centuries. Much of this work was developing theories about the way markets and market economies work. Much of this work has subsequently been updated by modern economists and they are generally termed neo-classical economists, the word neo meaning 'new'.

Short history of classical economics

Adam Smith, J.B. Say, Robert Malthus and David Richardo

In the year 1776, David Hume died while Jacques Turgot and Marquis de Condorcet left their government posts. But, in that same year, the intellectual revolution they had contributed to, the Enlightenment, began to bear its principal fruit. It was a year of grand treatises. Adam Smith published his Wealth of Nations, the Abbé de Condillac his Commerce et le Gouvernement,Jeremy Bentham his Fragments on Government and Tom Paine his Common Sense.

The Victorian period of rapid expansion worldwide seemed to cheer the Classical economists up quite a little and they became a more optimistic, but still maintained their total faith in the role of markets.

They believed that the government should not intervene to try to correct this as it would only make things worse and so the only way to encourage growth was to allow free trade and free markets.

This approach is known as a laissez-faire approach. Essentially this approach places total reliance on markets, and anything that prevent markets clearing properly should be done away with.

Much of Adam Smith's early work was on this theme, and he introduced the notion of an invisible hand that guided economic activity and led to the optimum equilibrium. Many people see him as the founding father of modern economics.

Written during the Enlightenment, the central messages of Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations (1776) — laissez-faire, the virtues of specialization, free trade and competition, etc.

In the struggle for apostolic succession, three names emerged as strong contenders:

- Robert Malthus and

They all had different visions for political economy after Smith. Say (1803) wanted to take it back towards the French-Italian demand-and-supply tradition. Malthus (1798, 1820) wanted to add a whole new emphasis, away from the obsessive intricacies of "value" and towards a more macroeconomic (and "dynamic") perspective. Ricardo (1817) wanted to do Smith all over again, but to do it properly this time.

Out of all three, David Ricardo turned out to be the most successful and influential. With his 1817 treatise, Ricardo took economics to an unprecedented degree of theoretical sophistication. Ricardo's theory, the most clearly and consistently formalized of them all, became the Classical system.

Classical Theory

Classical theories revolved mainly around the role of markets in the economy. If markets worked freely and nothing prevented their rapid clearing then the economy would prosper.

Any imperfections in the market that prevented this process should be dealt with by government. The main roles of government are therefore to ensure the free workings of markets using 'supply-side policies' and to ensure a balanced budget. The main theories used to justify this view were:

- Free market theory.

- Say's Law.

- Quantity Theory of Money.

Free market theory

The Classical economists assumed that if the economy was left to itself, then it would tend to full employment equilibrium. This would happen if the labour market worked properly. If there was any unemployment, then the following would happen:

unemployment increased demand for labour fall in wages equilibrium restored at ( a surplus of labour) full employment

As the Graph below illustrates, it is argued that there is an inverse relationship between the wage rate ( i.e. price of labour ) , depicted on the vertical “price” axis P, and the quantity of labor demanded, which is depicted ( as quantity of any other goods ) on the horizontal “quantity axis Q. There is also a “supply”( of labour ) curve S in this graph. This negative relationship between the wage and the quantity of labor demanded is the result of two effects:

In economics, the demand curve can be defined as the graph depicting the relationship between the price of a certain commodity, and the amount of it that consumers are willing and able to purchase at that given price (see demand).

- A substitution effect.

Suppose that the wage rate increases in the “demand” curve from D1to D2. The substitution effect of the wage increase involves the substitution of other resources (such as capital, energy, materials, and other categories of labor) for the category of labor that has become more expensive. As the wage rate rises from P1 to P2 , the substitution effect results in a reduction in the quantity of labor demanded; from Q2 ro Q1. Note that the “supply” of labour S is constant all through the process.

An equilibrium occurs in a labor market at the combination of wages and employment at which market demand and supply intersect ( as illustrated in the Diagram above. ) . If the wage rate is above the equilibrium, the quantity of labor supplied exceeds the quantity demanded and a surplus occurs. In this case, the existence of unemployed workers will be expected to result in downward pressure on the wage rate until an equilibrium is restored. If the wage rate is below the equilibrium, a labor shortage will occur. Competition among firms for workers is expected to result in increases in the wage until an equilibrium occurs.

- A scale effect.

The scale effect resulting from a wage increase is a bit more complex. As the wage rate rises, the scale effect involves the following chain of effects:

- (a) higher wages result in higher average and marginal costs of production,

- (b) higher average and marginal and average costs result in an increase in the equilibrium price of the product,

- (c) as the price of the product rises, the equilibrium quantity of the product demanded declines (a reduction in the "scale" of production), and

- (d) the reduction in output results in a reduction in the quantity of all inputs used to produce this product (including this category of labor).

===Say’s Law: Supply-side policies ===

So, Classical economists are of the view that the economy is self-adjusting. We can therefore sum up their policy recommendations in a variation on a well-known phrase: “…Don't just do something, sit there!’ Of course, taking this too literally would be unfair on Classical economists, but it would be true to say that because the economy tends to full-employment, there is no need to actively intervene in the economy. In fact intervention may simply be destabilising and inflationary. The key to long-term stable growth is therefore:

- Ensure free markets with no imperfections ( through supply-side policies )

- Control the growth of the money supply to ensure low inflation

For Say, the foundation of value is utility or the capacity of a good or service to satisfy some human desire. Those desires and the preferences, expectations, and customs that lie behind them must be taken as givens, as data, by the analyst. The task is to reason from those data. Say is most emphatic in denying the claims of Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and others that the basis for value is labor, or "…productive agency……" ( Say, 1803, p.348 )

Nowhere is Say's radicalism more evident than in his critique of government intervention into the economy. Most succinctly stated, he declares that self-interest and the search for profits will push entrepreneurs toward satisfying consumer demand. "…..the nature of the products is always regulated by the wants of society," therefore "legislative interference is superfluous altogether…..."( ibid., p.144 )

It was also in the Treatise ( Say, 1803 ) that Say outlined his famous "Law of Markets". Roughly stated, Say's Law claims that total demand in an economy cannot exceed or fall below total supply in that economy or as James Mill was to restate it, "…supply creates its own demand……"

In Say's language, "….products are paid for with products…." ( ibid., p.153) or "….a glut can take place only when there are too many means of production applied to one kind of product and not enough to another….."( ibid., p.178-9.).

Using supply-side policies can be seen in the above Diagram when we assume only one price level, say, P1 and we increase the level of output from Q1 to Q2, while the price level P1 has remained stable. Supply-side policies as we have said are ones that reduce market imperfections. They may include:

- Improving education & training to make the work-force more occupationally mobile

- Reducing the level of benefits to increase the incentive for people to work

- Reducing taxation to encourage enterprise and encourage hard work

- Policies to make people more geographically mobile (scrapping rent controls, simplifying house buying to speed it up, ......)

- Reducing the power of trade unions to allow wages to be more flexible

- Getting rid of any capital controls

- Removing unnecessary regulations

Quantity theory of money

The other area that Classical economists felt was important was to control monetary growth. In this way as predicted by the Quantity Theory of Money) they would be able to maintain low inflation. The Quantity Theory of Money ( QTM ) states that there is a direct relationship between the quantity of money in an economy and the level of prices of goods and services sold. According to QTM, if the amount of money in an economy doubles, price levels also double, causing inflation (the percentage rate at which the level of prices is rising in an economy). The consumer therefore pays twice as much for the same amount of the good or service.

In its simplest form, the theory is expressed as

- MV = PT (the Fisher Equation).

Each variable denotes the following:

M = Money Supply V = Velocity of Circulation (the number of times money changes hands) P = Average Price Level T = Volume of Transactions of Goods and Services

The original theory was considered orthodox among 17th century classical economists and was overhauled by 20th-century economists Irving Fisher, who formulated the above equation, and Milton Friedman ( Friedman, 1987 ) . It is built on the principle of ‘equation of exchange’:

- Amount of Money x Velocity of Circulation = Total Spending

Another way to understand this theory is to recognize that money is like any other commodity: increases in its supply decrease marginal value (the buying capacity of one unit of currency). So an increase in money supply causes prices to rise (inflation) as they compensate for the decrease in money’s marginal value.

Policies might include:

- Open-market operations.

- Funding.

- Monetary-base control.

- Interest rate control.

Classical Economics vs. The Exploitation Theory

“The exploitation theory” is one of the most powerful factors that have been operating to lead the world down The Road to Serfdom —as the title of Prof. Hayek's book describes the trend toward socialism ( Hayek, 1944. ) Indeed, the influence of the exploitation theory goes far beyond the direct and obvious support it gives to socialism. It has contributed to the triumph of socialism in more subtle ways, as well. It played a major, perhaps the decisive, role in the overthrow of British classical economics. Along with "the labor theory of value" and the "iron law of wages," they discarded such further features of classical political economy as the wages fund doctrine and its corollary that savings and capital are the source of almost all spending in the economic system. Two generations later, the abandonment of the classical doctrines on saving made possible the acceptance of Keynesianism and the policy of inflation, deficits, and ever expanding government spending. Similarly , the abandonment of the classical doctrine that cost of production, rather than supply and demand, is the direct (if not the ultimate) determinant of the prices of most manufactured or processed goods led, with just about the same time lag, to the promulgation of the doctrines of "pure and perfect competition," "oligopoly," "monopolistic competition," and "administered prices," with their implicit call for a policy of radical antitrust or outright nationalizations to "curb the abuses of big business." Thus, along these two further paths, the influence of the exploitation theory has served to advance the cause of socialism.

Smith and Marx vs. Bohm-Baverk

There are three aspects of classical economics which contribute to the exploitation theory. The two best known are:

- The labor theory of value and

- the iron law of wages.

Somewhat less prominent, but no less important, is the conceptual framework within which the exploitation theory is advanced. This framework is the belief that:

- Wages are the original and primary form of income, from which profits and all other non-wage incomes emerge as a deduction with the coming of capitalism and businessmen and capitalists.

It is on the basis of these beliefs that Adam Smith opens his chapter on wages in The Wealth of Nations with the words: “…..The produce of labour constitutes the natural recompense or wages of labour. In that original state of things, which precedes both the appropriation of land and the accumulation of stock, the whole produce of labour belongs to the labourer. He has neither landlord nor master to share with him…..”

In these, and other passages, Smith clearly advances the primacy of wages doctrine. That is, the doctrine that in a pre-capitalist economy—the "early and rude state of society"—in which workers simply produce and sell commodities and do not buy in order to sell, the incomes the workers receive are wages. “….Wages are the original income…”, according to Smith. “…..All income in the pre-capitalist society is supposed to be wages, and no income is supposed to be profit….,” according to Smith, “…..because workers are the only recipients of income….” At the same time, of course, Smith advances the corollary doctrine that profit emerges only with the coming of capitalism and is a deduction from what is naturally and, by implication, rightfully wages. These doctrines, appears to constitute the conceptual framework of the exploitation theory. They are the starting point for Marx ( Reisman 1985. ) Profits, then, according to both Smith and Marx, come into existence only with capitalism, and are a deduction from what naturally and rightfully belongs to the wage earners. This is not yet the exploitation theory itself, only the conceptual framework of the exploitation theory. It is a framework broad enough to include Marx, the leading proponent of the exploitation theory, and Böhm-Bawerk, its leading critic. Within this framework, Marx applies the labor theory of value and the iron law of wages, and arrives at the exploitation theory. Within this same framework, Böhm-Bawerk applies the discounting approach, and arrives at a critique of the exploitation theory ( Bohm-Bawerk, 1959. ) Both men call upon their respective doctrines to explain what makes possible the alleged deduction of profits from wages and what determines the size of this deduction. For classical economics implies that it is false to claim that wages are the original form of income and that profits are a deduction from them. This becomes apparent, as soon as we define our terms along classical lines:

- "Profit" is the excess of receipts from the sale of products over the money costs of producing them—over, it must be repeated, the money costs of producing them.

- A "capitalist" is one who buys in order subsequently to sell for a profit.

- "Wages" are money paid in exchange for the performance of labor—not for the products of labor, but for the performance of labor itself.

On the basis of these definitions it follows that, if there are merely workers producing and selling their products, the money which they receive in the sale of their products is not wages.

"…Demand for commodities….," to quote John Stuart Mill, "….is not demand for labour….. in buying commodities, one does not pay wages, and in selling commodities, one does not receive wages. …..”( Mill, 1976. )

Reevaluation of wages

Hence it is possible that, both, Smith and Marx are wrong. Wages are not the primary form of income in production. Profits are. In order for wages to exist in production, it is first necessary that there be capitalists. The emergence of capitalists does not bring into existence the phenomenon of profit. Profit exists prior to their emergence. The emergence of capitalists brings into existence the phenomena of wages and money costs of production. Accordingly, the profits which exist in a capitalist society are not a deduction from what was originally wages. On the contrary, the wages and the other money costs are a deduction from sales receipts—from what was originally all profit. The effect of capitalism is to create wages and to reduce profits relative to sales receipts. The more economically capitalistic the economy—the more the buying in order to sell relative to the sales receipts, the higher are wages and the lower are profits relative to sales receipts. Thus, capitalists do not impoverish wage earners, but make it possible for people to be wage earners. For they are responsible not for the phenomenon of profits, but for the phenomenon of wages. They are responsible for the very existence of wages in the production of products for sale. Without capitalists, the only way in which one could survive would be by means of producing and selling one's own products, namely, as a profit earner. But to produce and sell one's own products, one would have to own one's own land, and produce or have inherited one's own tools and materials. Relatively few people could survive in this way. The existence of capitalists makes it possible for people to live by selling their labor rather than attempting to sell the products of their labor. Thus, between wage earners and capitalists there is in fact the closest possible harmony of interests, for capitalists create wages and the ability of people to survive and prosper as wage earners. And if wage earners want a larger relative share for wages and a smaller relative share for profits, they should want a higher economic degree of capitalism—they should want more and bigger capitalists.

Wages determination solely by supply & demand

Once it is recognized that money wages are determined strictly by supply and demand, then it becomes clear that the wage earner's presumable willingness to work for a subsistence wage rather than die of starvation, and the capitalist's preference, other things equal, to pay lower wages rather than higher wages, are both irrelevant to the wage the worker must actually be paid. That wage is determined by the demand for and supply of labor. It can fall no lower than corresponds to the point of full employment. If it drops below that point, a labor shortage is created, which makes it to the self-interest of employers able and willing to pay a higher wage to bid wages up, so that they do not lose employees to other employers not able or willing to pay as much. In addition, wage rates themselves and prices of various materials determined by supply and demand are further factors entering into the determination of prices even in the domain where quantity of labor is relevant ( Mill, 1976.) And, as previously indicated, of course, determination of price by cost is never an ultimate determination, for the prices that constitute the costs are themselves determined by supply and demand and reflect the utility of marginal products, as Böhm-Bawerk explained ( Bohm-Bawerk, vol. 2.) And, to be sure, there are product prices which have no connection whatever to quantity of labor or cost of production in any form, but are determined exclusively by supply and demand, as Ricardo pointed out ( Ricardo, 1821, Chap.I,Sec.I. ) But also, it should be made clear, which the classical economists never succeeded in doing, that the quantity of labor as a determinant of prices is strictly confined to the category of reproducible products. Major categories of prices are in no way determined by it—above all, wage rates. Such prices are determined by supply and demand—by marginal utility, including the utility of marginal products. Nor are wages connected even indirectly with the "cost of production of labor." Of course, even within the domain of reproducible products, quantity of labor is by no means the only determinant of price. As Ricardo himself explained in Sections IV-VI of his chapter on value, the period of time for which profits must compound on wages before the ultimate, final product is sold to consumers is a second major determinant of prices ( Ricardo, op. cit.,Chap. I. )

Reevaluation of capitalists vs. workers coexistence

Historical confirmation of possibility of such a re-evaluation of can be found in Prof. Hayek's Introduction to Capitalism and the Historians. There we find such statements as: "…..The actual history of the connection between capitalism and the rise of the proletariat is almost the exact opposite of that which these theories of the expropriation of the masses suggest……."( Hayek, 1954. ) And: "…….The proletariat which capitalism can be said to have 'created' was thus not a proportion of the population which would have existed without it and which it degraded to a lower level; it was an additional population which was enabled to grow up by the new opportunities for employment which capitalism provided……."( ibid., 1954. ) But also, guiding and directing intelligence, not muscular exertion, is the essential characteristic of human labor. As von Mises says, "…..What produces the product are not toil and trouble in themselves, but the fact that the toiling is guided by reason……."( Mises, 1956. ) Guiding and directing intelligence in production is, of course, supplied by businessmen and capitalists on a higher level than by wage earners—a circumstance reinforcing the primary productive status of profits and profit earners over wages and wage earners. The precise nature of the work of businessmen and capitalists needs to be explained. In essence, it is to raise the productivity, and thus the real wages, of manual labor by means of creating, coordinating, and improving the efficiency of the division of labor. Several major functions could be easily acknowledged:

- (1) Businessmen and capitalists create division of labor in founding and organizing business firms and in providing capital.

- (2) Businessmen and capitalists coordinate the division of labor in seeking to avoid losses and to earn higher rates of return on their capital in preference to lower rates of return. They try to avoid over-expanding any industry relative to other industries and, at the same time, to be sure that any industry that is insufficiently expanded relative to other industries is further expanded. This is a major aspect of the significance of the principle, so well developed by the classical economists, that there is a tendency toward a uniform rate of profit on capital invested in all branches of industry ( Smith, Ricardo, Riesman op. cit. )

- (3) Businessmen and capitalists continuously improve the efficiency of production as the result both of their competitive quest for exceptional rates of profit and their saving and investment for the purpose of accumulating personal fortunes. The only way to earn an exceptional rate of profit where the legal freedom of competition prevails is by being an innovator in the production of better products or equally good but less expensive products. The exceptional profits from any given innovation then disappear as competitors begin to adopt it and make it into the normal standard of an industry. This requires that one introduce repeated innovations as the condition of continuing to earn an exceptional rate of profit. In this way, the entire benefit of every innovation tends to be passed forward to the consumers in the form of better products and lower prices, with exceptional profits being entirely transitory in the case of each particular innovation and a permanent phenomenon only insofar as improvement is continuous ( Reisman, 1996, p. 179. )

A Reinterpretation of Labor's Right to the Whole Produce

The fact that profits are an income attributable to the labor of businessmen and capitalists, and the further fact that their labor represents the provision of guiding and directing intelligence at the highest level in the productive process, suggests a radical reinterpretation of the doctrine of labor's right to the whole produce. Namely, that that right is satisfied when first the full product and then the full value of that product comes into the possession of businessmen and capitalists (which is exactly what occurs, of course, in the everyday operations of a market economy). For they, not the wage earners are the fundamental producers of products.

Summary and Conclusion

Despite the support which it historically gave to the “exploitation theory”, classical economics provides the basis for turning the exploitation theory upside down. On the basis of Ricardo's concept of profit and J. S. Mill's proposition that "demand for commodities is not demand for labour," it makes it possible to show how profits, not wages, must be regarded as the original and primary form of income, from which other incomes emerge as a deduction. And, further, not only how profits are a labor income (despite their variation with the size of the capital invested and the period of time for which it is invested), but how the labor of businessmen and capitalists has more fundamental responsibility for the production of products than the labor of wage earners, with the result that "labor's right to the whole produce" should mean the right of businessmen and capitalists to the sales receipts—a right which is honored every day, in the normal operations of a capitalist economy. In addition, the classical doctrines of supply and demand, the wage fund, the distinction between value and riches, and even the labor theory of value (appropriately modified along lines suggested by Ricardo and J. S. Mill and incorporating the advances in price theory made by Böhm-Bawerk) make possible an explanation of real wages based on the productivity of labor, which it is the economic function of businessmen and capitalists steadily to increase. Finally, it can be shown how socialism, with its universal state monopoly on employment and supply, is the economic system to which the exploitation theory actually applies.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Böhm-Bawerk, E. von.,Capital and Interest, op. cit., Vol. I, pp. 263-71; Vol. II, pp. 259-89, Libertarian Press, South Holland, Illinois 1959

- Fisher, I., The Purchasing Power of Money1911

- Friedman, M., “Quantity theory of money”, A Dictionary of Economics, The New Palgrave:, v. 4, 1987, p. 15.

- Hayek, F. A. ,The Road to Serfdom, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1944

- Hayek, F. A. editor, Capitalism and the Historians, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1954, pp. 15f.

- Hollander, J.,"The Development of the Theory of Money From Adam Smith to David Ricardo", Quarterly J. of Economics, 1910

- Laidler, D. The Golden Age of the Quantity Theory, Princeton

University Press. Princeton, NJ, 1991

- Mill, John S.,Principles of Political Economy, Bk. III, Chaps. III – VI, Ashley Edition (reprint, Fairfield, New Jersey) Augustus M. Kelley 1976

- Mises, Ludwig von, Human Action, Third Revised Edition, Henry Regnery Company, Chicago, 1966, p. 142.

- Newcomb, S. Principles of Political Economy'’, Harper, NY, 1885

- Reisman,G., “Classical Economics vs. The Exploitation Theory” in:The Political Economy of Freedom Essays in Honor of F. A. Hayek, Edited by Kurt R. Leube and Albert H. Zlabinger Philosophia Verlag, München and Wien, The International Carl Menger Library, 1985*Reisman, G., Capitalism: A Treatise on Economics, Jameson Books, Ottawa, IL, 1996, pp. 200-201, 206-209, 414-441

- Ricardo, David, Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, Third Edition, London 1821, Chap. IV

- Say, Jean-Baptiste, [ orig.1803], A Treatise on Political Economy: or the Production, Distribution and Consumption of Wealth, (translated by C.R. Prinsep and Clement C. Biddle) Augustus M. Kelley, New York 1971

- Smith, Adam, The Wealth of Nations, Cannan Edition, Bk. I, Chap. VIII.

- Smith, Adam op. cit.,Bk. I, Chap. X, Pt. I; Ricardo, David, Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, Third Edition, (London: 1821), Chap. IV. See also Reisman, Capitalism, pp. 172-180.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.