Difference between revisions of "Bryozoa" - New World Encyclopedia

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

Bryozoans attach to a variety of solid substrates, including rocks, shells, wood, sand grains, and blades of [[algae|kelp]], although some colonies form on sediment (Waggoner and Collins 1999). Bryozoan colonies also encrust pipes and ships, becoming a nuisance. Freshwater bryozoans may attach to tree roots and aquatic plants. | Bryozoans attach to a variety of solid substrates, including rocks, shells, wood, sand grains, and blades of [[algae|kelp]], although some colonies form on sediment (Waggoner and Collins 1999). Bryozoan colonies also encrust pipes and ships, becoming a nuisance. Freshwater bryozoans may attach to tree roots and aquatic plants. | ||

| − | + | Extant (living) bryozoans are typically immobile, sessile and colonial. However, there are bryozoan colonies that can move somewhat. And not all extant bryozoans are colonial and sessile. Waggoner and Collins (1999), basing their work on Buchsbaum et al. (1985), claim that there are a "few species of non-colonial bryozoans" that move about and live in the spaces between sand grains, and one species floats in the Southern Ocean (Antarctic Ocean). However, Ramel (2005) states that "all but one species are colonial," with the "single known solitary species, called ''Monobryozoon ambulans''," having been discovered in 1934 by A. Remone—an occurence that "was quite a surprise for the scientific community which until then had known all Bryozoans as colonial." (See also Gray 1971.) Inconsistency among biologists on whether entoprocts are included in bryozoa may be responsible for the discrepancy. | |

| − | + | Nonetheless, whether there are one or a few exceptions, bryozoans are characteristically colony-forming animals. Many millions of individuals can form one colony. The colonies range from millimeters to meters in size, but the individuals that make up the colonies are tiny, usually less than a millimeter long. In each colony, different individuals assume different functions. Some individuals gather up the food for the colony (autozooids), others depend on them (heterozooids). Some individuals are devoted to strengthening the colony (kenozooids), and still others to cleaning the colony (vibracula). | |

Bryozoans feed on [[microorganism]]s, including diatoms and unicellular [[algae]] and are preyed upon by fish and sea urchins (Waggoner and Collins 1999). Nudibranches and sea spiders also eat bryozoans. | Bryozoans feed on [[microorganism]]s, including diatoms and unicellular [[algae]] and are preyed upon by fish and sea urchins (Waggoner and Collins 1999). Nudibranches and sea spiders also eat bryozoans. | ||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

[[Image:Costazia_costazi.jpg|thumb|240px|''Costazia costazi'', a [[coralline]] bryozoan]] | [[Image:Costazia_costazi.jpg|thumb|240px|''Costazia costazi'', a [[coralline]] bryozoan]] | ||

| − | Bryozoan skeletons grow in a variety of shapes and patterns: mound-shaped, lacy fans, branching twigs, and even corkscrew-shaped. Their [[skeleton]]s have numerous tiny openings, each of which is the home of a minute animal called a ''zooid''. They also have a | + | Bryozoan skeletons grow in a variety of shapes and patterns: mound-shaped, lacy fans, branching twigs, and even corkscrew-shaped. Their [[skeleton]]s have numerous tiny openings, each of which is the home of a minute animal called a ''zooid''. They also have a coelomate body (having a true body cavity) with a looped alimentary canal or gut, opening at the [[mouth]] and terminating at the [[anus]]. |

| − | The tentacles of the bryozoans are ciliated, and the beating of the | + | Bryozoans feed with a specialized, [[cilia]]ted structure called a lophophore, which is a crown of [[tentacle]]s surrounding the mouth. Bryozoans do not have any defined respiratory, or circulatory systems due to their small size. However, they do have a hydrostatic skeletal system and a simple nervous system. |

| + | |||

| + | The tentacles of the bryozoans are ciliated, and the beating of the cilia creates a powerful current of water that drives water, together with entrained food particles (mainly [[plankton|phytoplankton]]), towards the mouth. The digestive system has a U-shaped gut, and consists of a [[pharynx]], which passes into the [[esophagus]], followed by the [[stomach]]. The stomach has three parts: the cardia, the caecum, and the pylorus. The pylorus leads to an intestine and a short [[rectum]] terminating at the anus, which opens outside the lophophore. In some groups, notably some ctenostomes, a specialized [[gizzard]] may be formed from the proximal part of the cardia. Gut and lophophore are the principal components of the polypide. Cyclical degeneration and regeneration of the polypide is characteristic of marine bryozoans. After the final polypide degeneration, the skeletal aperture of the feeding zooid may become sealed by the secretion of a terminal [[diaphragm]]. In many bryozoans ,only the zooids within a few generations of the growing edge are in an actively feeding state; older, more proximal zooids (e.g. in the interiors of bushy colonies) are usually dormant. | ||

[[Image:Freshwater Bryozoan234.JPG|thumb|left|240px|Freshwater bryozoan]] | [[Image:Freshwater Bryozoan234.JPG|thumb|left|240px|Freshwater bryozoan]] | ||

| Line 42: | Line 44: | ||

Because of their small size, bryozoans have no need of a [[blood]] system. Gaseous exchange occurs across the entire surface of the body, but particularly through the tentacles of the lophophore. | Because of their small size, bryozoans have no need of a [[blood]] system. Gaseous exchange occurs across the entire surface of the body, but particularly through the tentacles of the lophophore. | ||

| − | Bryozoans can reproduce both sexually and asexually. All Bryozoans, as far as is known, are [[hermaphroditic]] (meaning they are both male and female). [[Asexual reproduction]] occurs by budding off new zooids as the colony grows, and is the main way by which a colony expands in size. If a piece of a bryozoan colony breaks off, the piece can continue to grow and will form a new colony. A colony formed this way is composed entirely of [[Cloning|clones]] (genetically identical individuals) of the first animal, which is called the ''ancestrula''. | + | Bryozoans can reproduce both [[sexual reproduction|sexually]] and [[asexual reproduction|asexually]]. All Bryozoans, as far as is known, are [[hermaphroditic]] (meaning they are both male and female). [[Asexual reproduction]] occurs by budding off new zooids as the colony grows, and is the main way by which a colony expands in size. If a piece of a bryozoan colony breaks off, the piece can continue to grow and will form a new colony. A colony formed this way is composed entirely of [[Cloning|clones]] (genetically identical individuals) of the first animal, which is called the ''ancestrula''. |

| − | One species of bryozoan, ''Bugula neritina'', is of current interest as a source of | + | One species of bryozoan, ''Bugula neritina'', is of current interest as a source of cytotoxic chemicals, bryostatins, under clinical investigation as anti-[[cancer]] agents. |

==Fossils== | ==Fossils== | ||

| Line 68: | Line 70: | ||

Buchsbaum, R., M. Buchsbaum, J. Pearse, and V. Pearse. 1987. ''Animals Without Backbones'', 3rd Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. | Buchsbaum, R., M. Buchsbaum, J. Pearse, and V. Pearse. 1987. ''Animals Without Backbones'', 3rd Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ramel, G. 2005. [http://www.earthlife.net/inverts/bryozoa.html The Phylum Ectoprocta (Bryozoa)]. ''Earth Life Web''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Gray, J. S., 1971. | ||

| + | Occurrence of the aberrant bryozoan Monobryozoon ambulans Remane, off the Yorkshire coast. | ||

| + | Journal of Natural History 5: 113-117. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | . | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 01:55, 14 February 2007

| Bryozoa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

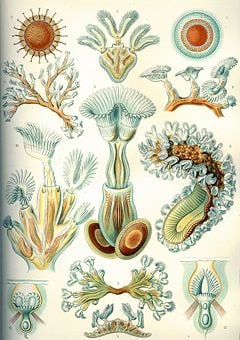

"Bryozoa", from Ernst Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur, 1904

| ||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||

| ||||||

|

Stenolaemata |

Bryozoa, also known as Ectoprocta, is a major invertebrate phyla, whose members, the bryozoans, are tiny, aquatic, and mostly sessile and colonial animals. Also known as moss animals or sea mats, bryozoans generally build stony skeletons of calcium carbonate, superficially similar to coral.

Bryozoa and Ectoprocta are generally considered synonymous, but historically Ectoprocta was considered one of two subgroups within Bryozoa, the other being Entoprocta, which most systematics now separate into its own phyla. (See classification. However, some biologiests still consider Ectoprocta and Entoprocta as subgroups within the larger grouping Bryozoa, whether or not they are accorded status as a sub-phyla or a phyla. The members are still known as bryozoans regardless if the phyla is known as Ectoprocta.

Bryozoans have a distinctive feeding organ called a lophophore found only in two other animal phyla, Phoronida (phoronid worms) and Brachiopoda (lamp shells). The lophophore is essentially a ciliated ribbon or string (Luria et al. 1981).

Bryozoans are found in marine, freshwater, and brackish environments. They generally prefer warm, tropical waters but are known to occur worldwide. There are about 5,000 living species, with several times that number of fossil forms known. Fossils are known from the early Ordovician period about 500 million years ago (MA).

Ecology

Most species of Bryozoan live in marine environments, though there are about 50 species which inhabit freshwater. Some marine colonies have been found at 8,200 meters below the surface, but most bryozoans inhabit shallower water (Waggoner and Collins 1999). Several bryozoan species can be found in the Midwestern United States, especially in the states of Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky, which used to be a part of a large ocean.

Bryozoans attach to a variety of solid substrates, including rocks, shells, wood, sand grains, and blades of kelp, although some colonies form on sediment (Waggoner and Collins 1999). Bryozoan colonies also encrust pipes and ships, becoming a nuisance. Freshwater bryozoans may attach to tree roots and aquatic plants.

Extant (living) bryozoans are typically immobile, sessile and colonial. However, there are bryozoan colonies that can move somewhat. And not all extant bryozoans are colonial and sessile. Waggoner and Collins (1999), basing their work on Buchsbaum et al. (1985), claim that there are a "few species of non-colonial bryozoans" that move about and live in the spaces between sand grains, and one species floats in the Southern Ocean (Antarctic Ocean). However, Ramel (2005) states that "all but one species are colonial," with the "single known solitary species, called Monobryozoon ambulans," having been discovered in 1934 by A. Remone—an occurence that "was quite a surprise for the scientific community which until then had known all Bryozoans as colonial." (See also Gray 1971.) Inconsistency among biologists on whether entoprocts are included in bryozoa may be responsible for the discrepancy.

Nonetheless, whether there are one or a few exceptions, bryozoans are characteristically colony-forming animals. Many millions of individuals can form one colony. The colonies range from millimeters to meters in size, but the individuals that make up the colonies are tiny, usually less than a millimeter long. In each colony, different individuals assume different functions. Some individuals gather up the food for the colony (autozooids), others depend on them (heterozooids). Some individuals are devoted to strengthening the colony (kenozooids), and still others to cleaning the colony (vibracula).

Bryozoans feed on microorganisms, including diatoms and unicellular algae and are preyed upon by fish and sea urchins (Waggoner and Collins 1999). Nudibranches and sea spiders also eat bryozoans.

Anatomy

Bryozoan skeletons grow in a variety of shapes and patterns: mound-shaped, lacy fans, branching twigs, and even corkscrew-shaped. Their skeletons have numerous tiny openings, each of which is the home of a minute animal called a zooid. They also have a coelomate body (having a true body cavity) with a looped alimentary canal or gut, opening at the mouth and terminating at the anus.

Bryozoans feed with a specialized, ciliated structure called a lophophore, which is a crown of tentacles surrounding the mouth. Bryozoans do not have any defined respiratory, or circulatory systems due to their small size. However, they do have a hydrostatic skeletal system and a simple nervous system.

The tentacles of the bryozoans are ciliated, and the beating of the cilia creates a powerful current of water that drives water, together with entrained food particles (mainly phytoplankton), towards the mouth. The digestive system has a U-shaped gut, and consists of a pharynx, which passes into the esophagus, followed by the stomach. The stomach has three parts: the cardia, the caecum, and the pylorus. The pylorus leads to an intestine and a short rectum terminating at the anus, which opens outside the lophophore. In some groups, notably some ctenostomes, a specialized gizzard may be formed from the proximal part of the cardia. Gut and lophophore are the principal components of the polypide. Cyclical degeneration and regeneration of the polypide is characteristic of marine bryozoans. After the final polypide degeneration, the skeletal aperture of the feeding zooid may become sealed by the secretion of a terminal diaphragm. In many bryozoans ,only the zooids within a few generations of the growing edge are in an actively feeding state; older, more proximal zooids (e.g. in the interiors of bushy colonies) are usually dormant.

Because of their small size, bryozoans have no need of a blood system. Gaseous exchange occurs across the entire surface of the body, but particularly through the tentacles of the lophophore.

Bryozoans can reproduce both sexually and asexually. All Bryozoans, as far as is known, are hermaphroditic (meaning they are both male and female). Asexual reproduction occurs by budding off new zooids as the colony grows, and is the main way by which a colony expands in size. If a piece of a bryozoan colony breaks off, the piece can continue to grow and will form a new colony. A colony formed this way is composed entirely of clones (genetically identical individuals) of the first animal, which is called the ancestrula.

One species of bryozoan, Bugula neritina, is of current interest as a source of cytotoxic chemicals, bryostatins, under clinical investigation as anti-cancer agents.

Fossils

Fossil bryozoans are found in rocks beginning in the early Ordovician. They were often major components of Ordovician seabed communities and, like modern-day bryozoans, played an important role in sediment stabilization and binding, as well as providing sources of food for other benthic organisms. During the Mississippian (354 to 323 million years ago) bryozoans were so common that their broken skeletons form entire limestone beds. Bryozoan fossil record comprises more than 1,000 described species. It is plausible that the Bryozoa existed in the Cambrian but were soft-bodied or not preserved for some other reason; perhaps they evolved from a phoronid-like ancestor at about this time.

Most fossil bryozoans have mineralized skeletons. The skeletons of individual zooids vary from tubular to box-shaped and contain a terminal aperture from which the lophophore is protruded to feed. No pores are present in the great majority of Ordovician bryozoans, but skeletal evidence shows that epithelia were continuous from one zooid to the next.

With regard to the bryozoan groups lacking mineralized skeletons, the statoblasts of freshwater phylactolaemates have been recorded as far back as the Permian, and the ctenostome fossils date only from the Triassic.

One of the most important events during bryozoan evolution was the acquisition of a calcareous skeleton and the related change in the mechanism of tentacle protrusion. The rigidity of the outer body walls allowed a greater degree of zooid contiguity and the evolution of massive, multiserial colony forms.

Classification

The Bryozoans were formerly considered to contain two subgroups: the Ectoprocta and the Entoprocta, based on the similar bodyplans and mode of life of these two groups. (Some researchers also included the Cycliophora, which are thought to be closely related to the Entoprocta.) However, the Ectoprocta are coelomate (possessing a body cavity) and their embryos undergo radial cleavage, while the Entoprocta are acoelemate and undergo spiral cleavage. Molecular studies are ambiguous about the exact position of the Entoprocta, but do not support a close relationship with the Ectoprocta. For these reasons, the Entoprocta are now considered a phylum of their own.[1] The removal of the 150 species of Entoprocta leaves Bryozoa synonymous with Ectoprocta; some authors have adopted the latter name for the group, but the majority continue to use the former.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ James W. Valentine (2004). On the origins of phyla. University of Chicago Press.

Ben Waggoner http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/bryozoa/bryozoalh.html Bryozoa: Life History and Ecology Allen G. Collins, 1999

Buchsbaum, R., M. Buchsbaum, J. Pearse, and V. Pearse. 1987. Animals Without Backbones, 3rd Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ramel, G. 2005. The Phylum Ectoprocta (Bryozoa). Earth Life Web.

Gray, J. S., 1971. Occurrence of the aberrant bryozoan Monobryozoon ambulans Remane, off the Yorkshire coast. Journal of Natural History 5: 113-117.

.

See also

- International Bryozoology Association

External links

- Index to Bryozoa Bryozoa Home Page, was at RMIT; now bryozoa.net

- Other Bryozoan WWW Resources

- International Bryozoology Association official website

- Bryozoan Introduction

- The Phylum Ectoprocta (Bryozoa)

- Phylum Bryozoa at Wikispecies

- Bryozoans in the Connecticut River

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.