Difference between revisions of "Bragi" - New World Encyclopedia

Chris Jensen (talk | contribs) |

Simona Brkic (talk | contribs) m (→References) |

||

| (11 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{copyedited}} |

| − | [[Image:Idunn and Bragi by Blommer.jpg|right|thumb|300px|Bragi is shown with a harp and accompanied by his wife | + | [[Image:Idunn and Bragi by Blommer.jpg|right|thumb|300px|Bragi is shown with a harp and accompanied by his wife Iðunn in this 19th century painting by Nils Blommér.]] |

| − | '''Bragi''' is the god of [[poetry]] in [[Norse mythology]]. | + | '''Bragi''' is the god of [[poetry]] in [[Norse Mythology|Norse mythology]]. Given the prominent role that poetry played in Nordic society (as it was the primary means of story-telling, the main method of maintaining historical records, and the initiator and promulgator of posthumous honors),<ref>Lindow, 12-23.</ref> Bragi was a relatively important deity in Norse mythology, despite the fact that he seems not to have been the subject of widespread veneration. Intriguingly, some sources suggest that this god was actually named after the poet, Bragi Boddason (c. ninth century C.E.) who was posthumously elevated to the ranks of the [[Aesir]] (the principle clan of gods in Norse Mythology). |

| − | ==Bragi in a Norse | + | ==Bragi in a Norse context== |

| − | |||

| − | As | + | As a Norse deity, Bragi belonged to a complex religious, mythological, and cosmological belief system shared by the Scandinavian and Germanic peoples. This mythological tradition, of which the Scandinavian (and particularly Icelandic) sub-groups are best preserved, developed in the period from the first manifestations of religious and material culture in approximately 1000 B.C.E. until the Christianization of the area, a process that occurred primarily from 900-1200 C.E.<ref>Lindow, 6-8.</ref> However, some scholars have argued against the homogenizing effect of grouping these various traditions together under the rubric of “Norse Mythology.” The profoundly exploratory/nomadic nature of Viking society tends to overrule such objections. As Thomas DuBois cogently argues, “[w]hatever else we may say about the various peoples of the North during the Viking Age, then, we cannot claim that they were isolated from or ignorant of their neighbors…. As religion expresses the concerns and experiences of its human adherents, so it changes continually in response to cultural, economic, and environmental factors. Ideas and ideals passed between communities with frequency and regularity, leading to and interdependent and intercultural region with broad commonalities of religion and worldview.” (27-28). |

| + | |||

| + | The tales recorded within this mythological corpus tend to exemplify a unified cultural focus on physical prowess and military might. | ||

| − | Within this framework, Norse cosmology postulates three separate "clans" of deities: | + | Within this framework, Norse cosmology postulates three separate "clans" of deities: The [[Aesir]], the [[Vanir]], and the [[Jotun]]. The distinction between Aesir and Vanir is relative, for the two are said to have made peace, exchanged hostages, intermarried, and reigned together after a prolonged war. In fact, the most major divergence between the two groups is in their respective areas of influence, with the Aesir representing war and conquest, and the Vanir representing exploration, fertility, and wealth. (More specifically, Georges Dumézil, one of the foremost authorities on the Norse tradition and a noted comparitivist, argues quite persuasively that the Aesir/Vanir distinction is a component of a larger triadic division between ruler gods, warrior gods, and gods of agriculture and commerce, that is echoed among the Indo-European cosmologies. Further, he notes that this distinction conforms to patterns of social organization found in all of these societies.</ref> The ''Jotun,'' on the other hand, are seen as a generally malefic (though wise) race of giants who represented the primary adversaries of the Aesir and Vanir. |

| − | Bragi is described in some mythic accounts (especially the Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson) as a god of ''skalds'' (Nordic poets) whose father was Odin and who, resultantly, was one of the Aesir. However, other traditions | + | Bragi is described in some mythic accounts (especially the ''Prose Edda'' of Snorri Sturluson) as a god of ''skalds'' (Nordic poets) whose father was [[Odin]] and who, resultantly, was one of the Aesir. However, other traditions create the strong implication that Bragi was, in fact, a ''euhemerized'' version of a popular eight/ninth century poet. |

| − | ==Characteristics and | + | ==Characteristics and mythic representations== |

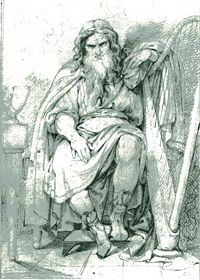

[[Image:Bragi by Wahlbom.jpg|thumb|200px|right|Bragi by Carl Wahlbom (1810-1858).]] | [[Image:Bragi by Wahlbom.jpg|thumb|200px|right|Bragi by Carl Wahlbom (1810-1858).]] | ||

| − | + | ''Bragi'' is generally associated with ''bragr,'' the Norse word for [[poetry]]. The name of the god may have been derived from ''bragr,'' or the term ''bragr'' may have been formed to describe "what Bragi does." | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | In | + | The majority of descriptions of the deity can be found in the ''Prose Edda,'' written by [[Snorri Sturluson]] (1178-1241 C.E.). In the section titled, ''Gylfaginning'' Snorri writes: |

| + | :One [of the gods] is called Bragi: He is renowned for wisdom, and most of all for fluency of speech and skill with words. He knows most of skaldship, and after him skaldship is called ''bragr,'' and from his name that one is called ''bragr''-man or -woman, who possesses eloquence surpassing others, of women or of men. His wife is [[Iðunn]].<ref>Snorri Sturluson, ''Gylfaginning'' (XXVI), (Brodeur 39).</ref> | ||

| + | Refining this characterization in the ''Skáldskaparmál'' (a guide for aspiring poets ''(skalds)''), Snorri writes: | ||

| + | :How should one paraphrase Bragi? By calling him ''husband of Iðunn,'' ''first maker of poetry,'' and ''the long-bearded god'' (after his name, a man who has a great beard is called Beard-Bragi), and ''son of Odin''.<ref>Snorri Sturluson, ''Skáldskaparmál'' (X), (Brodeur 113).</ref> | ||

| − | + | Though this verse (and a few others within the ''Prose Edda'') testify that Bragi is Odin's son, it is not an attribution that is borne out through the remainder of the literature. As Orchard notes, in the majority of "pre-Snorri" references to Bragi, it is ambiguous whether the text is referring to the deceased poet or to a god by the same name (70). | |

| − | < | + | A role frequently played by Nordic ''skalds'' (poets) was to provide entertainment and enlightenment at the royal courts.<ref>Lindow, 12-24.</ref> In a similar manner, Bragi is most often depicted in [[Valhalla]]—the meeting hall of the [[Aesir]]—greeting the souls of the newly departed and weaving poetic tales for the assembled divinities. One instance of the fulfillment of this role can be seen in the elegiac poem ''Eiríksmál,'' where Bragi welcomes the soul of [[Norway|Norwegian]] king Eirík Bloodaxe (whose widow had commissioned the poem) into the divine hall. Likewise, in the poem ''Hákonarmál,'' Hákon the Good is taken to Valhalla by the [[valkyrie]] Göndul, at which point Odin sends Hermóðr and Bragi to greet him. That Bragi was also the first to speak to Loki in the ''Lokasenna'' as [[Loki]] attempted to enter the hall might be an additional parallel.<ref>Orchard, 70</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | + | In the ''Lokasenna'', Bragi is seen exchanging rhymed insults and taunts with [[Loki]] (the god of mischief and discord), a testament to his verbal abilities: | |

| − | + | : ''(Loki)'' | |

| + | : Greetings, gods; greetings goddesses, | ||

| + | : and all the most holy powers, | ||

| + | : except that one god, who sits furthest in, | ||

| + | : Bragi, at the benches' end. | ||

| + | : ''(Bragi)'' | ||

| + | : A horse and sword, will I give from my hoard, | ||

| + | : and Bragi will requite you with a ring, | ||

| + | : if only you'll check your malice at the gods: | ||

| + | : don't anger the Aesir against you! | ||

| + | : ''(Loki)'' | ||

| + | : As for horses and arm-rings, | ||

| + | : Bragi, you'll always lack both: | ||

| + | : of the Aesit and elves who are gathered here, | ||

| + | : you are the wariest of war, | ||

| + | : even the most shy of shooting. | ||

| + | : ''(Bragi)'' | ||

| + | : I know, if only I were outside, | ||

| + | : as I'm inside, Aegir's hall, | ||

| + | : I'd have your head held in my hand: | ||

| + | : I'll pay you back for that lie. | ||

| + | : ''(Loki)'' | ||

| + | : You're a soldier in your seat, but you can't deliver, | ||

| + | : Bragi, pretty boy on a bench: | ||

| + | : go and get moving if you're enraged: | ||

| + | : no hero takes heed of the consequences.<ref>''Lokasenna,'' quoted in Orchard, 71.</ref> | ||

| − | + | A further testament to the importance of Bragi can be found in the prefatory and interstitial material of Snorri's ''Skáldskaparmál'' ("The Poesy of the Skalds"), where Bragi is seen exploring the mythical context for the development of poetry in human society and instructing aspiring poets in the techniques, stylistic devices, and subject matter of the ''skaldic'' tradition—a fact that says as much about the role of poetry in Nordic society as it does about the relative importance of the god.<ref>See ''Skáldskaparmál'' (Brodeur, 87-240).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Intriguingly, in the majority of these cases Bragi could be either a god or a dead hero in Valhalla. While [[Snorri Sturluson]] does quote from the poet Bragi Boddason (c. ninth century C.E.), who seems to be distinguished from the god Bragi, this does not negate the fact that the two could have been conflated prior to Snorri's time. Supporting this reading, Turville-Petre argues: | |

| − | + | :We must wonder whether the Bragi named in the Lays of Eirík and of Hákon is the god of poetry or the historical poet who, with other heroes, had joined Odin's chosen band. We may even wonder whether we should not identify the two. This would imply that the historical poet, like other great men, had been raised to the status of godhead after death. (The process of venerating ancestors and deceased human heroes is well described in DuBois.) The suspicion grows deeper when it is realized that the name "Bragi" was applied to certain other legendary and historical figures, and that gods' names are rarely applied to men.<ref>Turville-Petre, 185.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Bragi Boddason== | ==Bragi Boddason== | ||

| − | + | If Bragi was, in fact, a ''euhemerized'' human, it is likely that he began as '''Bragi Boddason the old''' ''(Bragi Boddason inn gamli)'', a court poet who served several Swedish kings ([[Ragnar Lodbrok]], [[Östen Beli]], and [[Björn at Hauge]]) who reigned in the first half of the ninth century. This Bragi was reckoned as the first skaldic poet, and was certainly the earliest skaldic poet then remembered by name whose verse survived in memory. If Bragi (the god) was originally derived from this individual, it would certainly explain the ''Eddic'' assertion that Bragi could be addressed as "First Maker of Poetry."<ref>Snorri Sturluson, Skáldskaparmál (X), (Brodeur, 113).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

| − | == | + | ==References== |

| − | * DuBois, Thomas A. ''Nordic Religions in the Viking Age''. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999. ISBN | + | * DuBois, Thomas A. ''Nordic Religions in the Viking Age''. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999. ISBN 0812217144 |

| − | * Dumézil, Georges. ''Gods of the Ancient Northmen'' | + | * Dumézil, Georges. ''Gods of the Ancient Northmen''. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973. ISBN 0520020448 |

| − | * Lindow, John. ''Handbook of Norse mythology''. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001. ISBN | + | * Lindow, John. ''Handbook of Norse mythology''. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001. ISBN 1576072177 |

| − | * Munch, P. A. ''Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes''. | + | * Munch, P. A. ''Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes''. London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1926. |

| − | * Orchard, Andy. ''Cassell's Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend''. London: Cassell | + | * Orchard, Andy. ''Cassell's Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend''. London: Cassell, 2002. ISBN 0304363855 |

| − | * Sturlson, Snorri. ''The Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson: Tales from Norse Mythology'' | + | * Sturlson, Snorri. ''The Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson: Tales from Norse Mythology''. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1954. ISBN 0520012313 |

| − | * Snorri Sturluson. ''The Prose Edda'' | + | * Snorri Sturluson. ''The Prose Edda''. New York: American-Scandinavian foundation, 1916. |

| − | * Turville-Petre, Gabriel. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964. | + | * Turville-Petre, Gabriel. ''Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia.'' New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964. |

[[Category: Philosophy and religion]] | [[Category: Philosophy and religion]] | ||

Latest revision as of 14:56, 28 April 2020

Bragi is the god of poetry in Norse mythology. Given the prominent role that poetry played in Nordic society (as it was the primary means of story-telling, the main method of maintaining historical records, and the initiator and promulgator of posthumous honors),[1] Bragi was a relatively important deity in Norse mythology, despite the fact that he seems not to have been the subject of widespread veneration. Intriguingly, some sources suggest that this god was actually named after the poet, Bragi Boddason (c. ninth century C.E.) who was posthumously elevated to the ranks of the Aesir (the principle clan of gods in Norse Mythology).

Bragi in a Norse context

As a Norse deity, Bragi belonged to a complex religious, mythological, and cosmological belief system shared by the Scandinavian and Germanic peoples. This mythological tradition, of which the Scandinavian (and particularly Icelandic) sub-groups are best preserved, developed in the period from the first manifestations of religious and material culture in approximately 1000 B.C.E. until the Christianization of the area, a process that occurred primarily from 900-1200 C.E.[2] However, some scholars have argued against the homogenizing effect of grouping these various traditions together under the rubric of “Norse Mythology.” The profoundly exploratory/nomadic nature of Viking society tends to overrule such objections. As Thomas DuBois cogently argues, “[w]hatever else we may say about the various peoples of the North during the Viking Age, then, we cannot claim that they were isolated from or ignorant of their neighbors…. As religion expresses the concerns and experiences of its human adherents, so it changes continually in response to cultural, economic, and environmental factors. Ideas and ideals passed between communities with frequency and regularity, leading to and interdependent and intercultural region with broad commonalities of religion and worldview.” (27-28).

The tales recorded within this mythological corpus tend to exemplify a unified cultural focus on physical prowess and military might.

Within this framework, Norse cosmology postulates three separate "clans" of deities: The Aesir, the Vanir, and the Jotun. The distinction between Aesir and Vanir is relative, for the two are said to have made peace, exchanged hostages, intermarried, and reigned together after a prolonged war. In fact, the most major divergence between the two groups is in their respective areas of influence, with the Aesir representing war and conquest, and the Vanir representing exploration, fertility, and wealth. (More specifically, Georges Dumézil, one of the foremost authorities on the Norse tradition and a noted comparitivist, argues quite persuasively that the Aesir/Vanir distinction is a component of a larger triadic division between ruler gods, warrior gods, and gods of agriculture and commerce, that is echoed among the Indo-European cosmologies. Further, he notes that this distinction conforms to patterns of social organization found in all of these societies.</ref> The Jotun, on the other hand, are seen as a generally malefic (though wise) race of giants who represented the primary adversaries of the Aesir and Vanir.

Bragi is described in some mythic accounts (especially the Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson) as a god of skalds (Nordic poets) whose father was Odin and who, resultantly, was one of the Aesir. However, other traditions create the strong implication that Bragi was, in fact, a euhemerized version of a popular eight/ninth century poet.

Characteristics and mythic representations

Bragi is generally associated with bragr, the Norse word for poetry. The name of the god may have been derived from bragr, or the term bragr may have been formed to describe "what Bragi does."

The majority of descriptions of the deity can be found in the Prose Edda, written by Snorri Sturluson (1178-1241 C.E.). In the section titled, Gylfaginning Snorri writes:

- One [of the gods] is called Bragi: He is renowned for wisdom, and most of all for fluency of speech and skill with words. He knows most of skaldship, and after him skaldship is called bragr, and from his name that one is called bragr-man or -woman, who possesses eloquence surpassing others, of women or of men. His wife is Iðunn.[3]

Refining this characterization in the Skáldskaparmál (a guide for aspiring poets (skalds)), Snorri writes:

- How should one paraphrase Bragi? By calling him husband of Iðunn, first maker of poetry, and the long-bearded god (after his name, a man who has a great beard is called Beard-Bragi), and son of Odin.[4]

Though this verse (and a few others within the Prose Edda) testify that Bragi is Odin's son, it is not an attribution that is borne out through the remainder of the literature. As Orchard notes, in the majority of "pre-Snorri" references to Bragi, it is ambiguous whether the text is referring to the deceased poet or to a god by the same name (70).

A role frequently played by Nordic skalds (poets) was to provide entertainment and enlightenment at the royal courts.[5] In a similar manner, Bragi is most often depicted in Valhalla—the meeting hall of the Aesir—greeting the souls of the newly departed and weaving poetic tales for the assembled divinities. One instance of the fulfillment of this role can be seen in the elegiac poem Eiríksmál, where Bragi welcomes the soul of Norwegian king Eirík Bloodaxe (whose widow had commissioned the poem) into the divine hall. Likewise, in the poem Hákonarmál, Hákon the Good is taken to Valhalla by the valkyrie Göndul, at which point Odin sends Hermóðr and Bragi to greet him. That Bragi was also the first to speak to Loki in the Lokasenna as Loki attempted to enter the hall might be an additional parallel.[6]

In the Lokasenna, Bragi is seen exchanging rhymed insults and taunts with Loki (the god of mischief and discord), a testament to his verbal abilities:

- (Loki)

- Greetings, gods; greetings goddesses,

- and all the most holy powers,

- except that one god, who sits furthest in,

- Bragi, at the benches' end.

- (Bragi)

- A horse and sword, will I give from my hoard,

- and Bragi will requite you with a ring,

- if only you'll check your malice at the gods:

- don't anger the Aesir against you!

- (Loki)

- As for horses and arm-rings,

- Bragi, you'll always lack both:

- of the Aesit and elves who are gathered here,

- you are the wariest of war,

- even the most shy of shooting.

- (Bragi)

- I know, if only I were outside,

- as I'm inside, Aegir's hall,

- I'd have your head held in my hand:

- I'll pay you back for that lie.

- (Loki)

- You're a soldier in your seat, but you can't deliver,

- Bragi, pretty boy on a bench:

- go and get moving if you're enraged:

- no hero takes heed of the consequences.[7]

A further testament to the importance of Bragi can be found in the prefatory and interstitial material of Snorri's Skáldskaparmál ("The Poesy of the Skalds"), where Bragi is seen exploring the mythical context for the development of poetry in human society and instructing aspiring poets in the techniques, stylistic devices, and subject matter of the skaldic tradition—a fact that says as much about the role of poetry in Nordic society as it does about the relative importance of the god.[8]

Intriguingly, in the majority of these cases Bragi could be either a god or a dead hero in Valhalla. While Snorri Sturluson does quote from the poet Bragi Boddason (c. ninth century C.E.), who seems to be distinguished from the god Bragi, this does not negate the fact that the two could have been conflated prior to Snorri's time. Supporting this reading, Turville-Petre argues:

- We must wonder whether the Bragi named in the Lays of Eirík and of Hákon is the god of poetry or the historical poet who, with other heroes, had joined Odin's chosen band. We may even wonder whether we should not identify the two. This would imply that the historical poet, like other great men, had been raised to the status of godhead after death. (The process of venerating ancestors and deceased human heroes is well described in DuBois.) The suspicion grows deeper when it is realized that the name "Bragi" was applied to certain other legendary and historical figures, and that gods' names are rarely applied to men.[9]

Bragi Boddason

If Bragi was, in fact, a euhemerized human, it is likely that he began as Bragi Boddason the old (Bragi Boddason inn gamli), a court poet who served several Swedish kings (Ragnar Lodbrok, Östen Beli, and Björn at Hauge) who reigned in the first half of the ninth century. This Bragi was reckoned as the first skaldic poet, and was certainly the earliest skaldic poet then remembered by name whose verse survived in memory. If Bragi (the god) was originally derived from this individual, it would certainly explain the Eddic assertion that Bragi could be addressed as "First Maker of Poetry."[10]

Notes

- ↑ Lindow, 12-23.

- ↑ Lindow, 6-8.

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning (XXVI), (Brodeur 39).

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Skáldskaparmál (X), (Brodeur 113).

- ↑ Lindow, 12-24.

- ↑ Orchard, 70

- ↑ Lokasenna, quoted in Orchard, 71.

- ↑ See Skáldskaparmál (Brodeur, 87-240).

- ↑ Turville-Petre, 185.

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Skáldskaparmál (X), (Brodeur, 113).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- DuBois, Thomas A. Nordic Religions in the Viking Age. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999. ISBN 0812217144

- Dumézil, Georges. Gods of the Ancient Northmen. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973. ISBN 0520020448

- Lindow, John. Handbook of Norse mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001. ISBN 1576072177

- Munch, P. A. Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes. London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1926.

- Orchard, Andy. Cassell's Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. London: Cassell, 2002. ISBN 0304363855

- Sturlson, Snorri. The Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson: Tales from Norse Mythology. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1954. ISBN 0520012313

- Snorri Sturluson. The Prose Edda. New York: American-Scandinavian foundation, 1916.

- Turville-Petre, Gabriel. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.