Difference between revisions of "Bohemia" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

The mid-13th century saw the beginning of substantial German immigration as the court sought to replace losses from the brief [[Mongolia|Mongol]] invasion of [[Europe]] in 1241. The Germans settled primarily along the northern, western, and southern borders of Bohemia, although many lived in towns throughout the kingdom. | The mid-13th century saw the beginning of substantial German immigration as the court sought to replace losses from the brief [[Mongolia|Mongol]] invasion of [[Europe]] in 1241. The Germans settled primarily along the northern, western, and southern borders of Bohemia, although many lived in towns throughout the kingdom. | ||

| − | + | ==Luxembourg dynasty== | |

| + | ===John=== | ||

The death of the last Premyslid duke, Wenceslas III (Václav III), sent the Czech dukes to a period of hesitation as to the choice of the Czech king, until they selected John of Luxembourg “Blind”, the son of Friedrich VII, the king of Germany and Roman Empire, in 1310, with condititions, including extensive concessions to the Czech dukes. John married the sister of the last Premyslid but the Czech kingdom was an unexplored territory for him; he did not understand the customs or needs of the country. He ruled as the King of Bohemia in 1310-1346 and the King of Poland in 1310-1335. Being a shrewd politician nicknamed “King Diplomat”, John annexed Upper [[Silesia]] and most Silesian duchies to Bohemia, and had his sights set at northern [[Italy]] as well. In 1335, he gave up all claims to the Polish throne. | The death of the last Premyslid duke, Wenceslas III (Václav III), sent the Czech dukes to a period of hesitation as to the choice of the Czech king, until they selected John of Luxembourg “Blind”, the son of Friedrich VII, the king of Germany and Roman Empire, in 1310, with condititions, including extensive concessions to the Czech dukes. John married the sister of the last Premyslid but the Czech kingdom was an unexplored territory for him; he did not understand the customs or needs of the country. He ruled as the King of Bohemia in 1310-1346 and the King of Poland in 1310-1335. Being a shrewd politician nicknamed “King Diplomat”, John annexed Upper [[Silesia]] and most Silesian duchies to Bohemia, and had his sights set at northern [[Italy]] as well. In 1335, he gave up all claims to the Polish throne. | ||

| − | In 1334, | + | ===Charles IV=== |

| + | In 1334, John appointed his oldest son [[Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor|Charles IV]] as the de facto administrator of Czech lands, setting off the period of Luxembourg dual reign, and six years later he safeguarded the Czech crown for him as well as Charles’ endeavors to obtain the Roman kingship, in which Charles succeeded in 1346, still during his father’s life. Charles IV was crowned as the King of Bohemia in 1346 and labored to uplift not only Bohemia but also the rest of Europe. As the Holy Roman Emperor and the Czech king, dubbed the “Father of the Country”, he is the most notable European ruler of the late Middle Ages. In line with the Luxembourg tradition, Charles IV was sent at a very young age to the French court, where he received extensive education and acquired mastery of German, French, Latin, and Italian languages. Czech language was the closest to his heart though, and two years into his election as king, he founded central Europe's first university, Charles University in Prague. | ||

In 1355, Charles IV ascended to the Roman throne, and a year later he issued the Golden bula of Charles IV, a set of statutes to be valid in the Holy Roman Empire until 1806. His reign brought Bohemia to its peak both in terms of policy and territory; the Bohemian crown controlled such diverse lands as Moravia, Silesia, Upper Lusatia and Lower Lusatia, Brandenburg, an area around Nuremberg called New Bohemia, [[Luxembourg]], and several small towns scattered around Germany. On the home turf, he triggered an unprecedented economic, cultural and artistic boom in [[Prague]] and the rest of Bohemia. On the home turf, he triggered an unprecedented economic, cultural and artistic boom in Bohemia, refusing to move to Rome and instituting Prague as the imperial capital. Construction in Prague was in the full swing, and many sights bear his name. The Prague Castle and much of the Saint Vitus Cathedral were completed under his patronage. The Czech Republic labels him Father of the Country (Pater patriae in Latin), a title first coined at his funeral. His imperial policy was focused on the economic and intellectual development of Bohemia; he corresponded with Petrarch, the initiator of Renaissance Humanism, who hoped in vain that Charles IV would transfer the capital of the Holy Roman Empire from Prague to Rome and renew the glory of the Empire. | In 1355, Charles IV ascended to the Roman throne, and a year later he issued the Golden bula of Charles IV, a set of statutes to be valid in the Holy Roman Empire until 1806. His reign brought Bohemia to its peak both in terms of policy and territory; the Bohemian crown controlled such diverse lands as Moravia, Silesia, Upper Lusatia and Lower Lusatia, Brandenburg, an area around Nuremberg called New Bohemia, [[Luxembourg]], and several small towns scattered around Germany. On the home turf, he triggered an unprecedented economic, cultural and artistic boom in [[Prague]] and the rest of Bohemia. On the home turf, he triggered an unprecedented economic, cultural and artistic boom in Bohemia, refusing to move to Rome and instituting Prague as the imperial capital. Construction in Prague was in the full swing, and many sights bear his name. The Prague Castle and much of the Saint Vitus Cathedral were completed under his patronage. The Czech Republic labels him Father of the Country (Pater patriae in Latin), a title first coined at his funeral. His imperial policy was focused on the economic and intellectual development of Bohemia; he corresponded with Petrarch, the initiator of Renaissance Humanism, who hoped in vain that Charles IV would transfer the capital of the Holy Roman Empire from Prague to Rome and renew the glory of the Empire. | ||

| + | ===Sigismund=== | ||

Charles IV’s son Emperor [[Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor|Sigismund of Luxemburg]], the last of the House of Luxembourg on the Czech throne, as well as the King of Hungary and Holy Roman Emperor, has left behind a legacy of contradictions. He lost the Polish crown in 1384 but gained the Hungarian crown in 1387. In an effort to secure the Dalmatian coast under his reign, he organized a crusade but was defeated by the Osman Turks. After internment by the Hungarian nobility in 1401, he refocused his efforts on Bohemia and lent his support to the higher nobility fighting his step-brother, King Wenceslas IV, whom he later took hostage and transferred to Vienna for over a year. As an administrator of the Czech Kingdom appointed by Wenceslas IV, he took over the Czech crown. After the brothers’ reconciliation in 1404, Sigismund returned to Hungary, where he calmed down political turbulences and initiated an economic and cultural boom, granting privileges to cities, which he considered as the cornerstone of his rule. He also considered the Church subordinate to secular rule, and in 1403-1404, after disputes with the pope, he banned monetary appropriations for the Church and manned bishoprics and other religious institutions. | Charles IV’s son Emperor [[Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor|Sigismund of Luxemburg]], the last of the House of Luxembourg on the Czech throne, as well as the King of Hungary and Holy Roman Emperor, has left behind a legacy of contradictions. He lost the Polish crown in 1384 but gained the Hungarian crown in 1387. In an effort to secure the Dalmatian coast under his reign, he organized a crusade but was defeated by the Osman Turks. After internment by the Hungarian nobility in 1401, he refocused his efforts on Bohemia and lent his support to the higher nobility fighting his step-brother, King Wenceslas IV, whom he later took hostage and transferred to Vienna for over a year. As an administrator of the Czech Kingdom appointed by Wenceslas IV, he took over the Czech crown. After the brothers’ reconciliation in 1404, Sigismund returned to Hungary, where he calmed down political turbulences and initiated an economic and cultural boom, granting privileges to cities, which he considered as the cornerstone of his rule. He also considered the Church subordinate to secular rule, and in 1403-1404, after disputes with the pope, he banned monetary appropriations for the Church and manned bishoprics and other religious institutions. | ||

| − | As a Roman king, Sigismund sought to reform the Roman Church and settle the papal schism, a token of which was the convening of the Council of Constance in 1415, the rector of Charles University and a prominent reformer and religious thinker [[Jan Hus]] was sentenced to be burned at the stake as a [[heretic]], with the king’s undeniable involvement. Hus was invited to attend the council to defend himself and the Czech positions in the religious court, but with the emperor's approval, he was executed on July 6, 1415. His execution of Hus, as well as a papal [[crusade]] against the | + | As a Roman king, Sigismund sought to reform the Roman Church and settle the papal schism, a token of which was the convening of the Council of Constance in 1415, the rector of Charles University and a prominent reformer and religious thinker [[Jan Hus]] was sentenced to be burned at the stake as a [[heresy|heretic]], with the king’s undeniable involvement. Hus was invited to attend the council to defend himself and the Czech positions in the religious court, but with the emperor's approval, he was executed on July 6, 1415. His execution of Hus, as well as a papal [[crusade]] against the Hussites and [[John Wycliffe]], outraged the Czechs. Their ensuing rebellion against Romanists became known as the Hussite Wars. |

| − | + | Although a natural successor to Wenceslas IV, as a Czech king, Sigismund, who inherited the Czech throne in 1420, grappled with defiance from the Hussites, whom he unsuccessfully sought to subdue in repeated crusades. Only in 1436, after he agreed to reconciliatory terms between the Hussites and the Catholic Church, was he recognized as the Czech king. One year later he died. | |

| − | + | ==Hussite Bohemia== | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ''You who are warriors of God | |

| − | + | and his law. | |

| − | + | Ask God for help | |

| − | + | and hope in him | |

| − | + | that in his name | |

| − | + | you may gloriously triumph. | |

| − | + | '' | |

| − | + | (Hussite battle hymn) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The largely peasant uprising against imperial forces was led by a former mercenary, | + | The largely peasant uprising against imperial forces was led by a former mercenary, Jan Žižka of Trocnov. As the leader of the Hussite armies, he utilized innovative tactics and weapons, such as [[howitzer]]s, [[pistol]]s (from Czech ''píšťala'', the flute), and [[Wagenburg|fortified wagons]], which were revolutionary for the time and established Žižka as a great general. |

After Žižka's death, [[Prokop the Great]] took over the command for the army, and under his lead the Hussites were victorious for another ten years, to the sheer terror of Europe. The Hussite cause gradually splintered into two main factions, the moderate [[Utraquism|Utraquist]]s and the more fanatic [[Taborite]]s. After the [[Utraquists]] reunited with the Catholic Church, they were able to defeat the Taborites in the [[Battle of Lipany]] in 1434. Sigismund said after the battle that "only the Bohemians could defeat the Bohemians." | After Žižka's death, [[Prokop the Great]] took over the command for the army, and under his lead the Hussites were victorious for another ten years, to the sheer terror of Europe. The Hussite cause gradually splintered into two main factions, the moderate [[Utraquism|Utraquist]]s and the more fanatic [[Taborite]]s. After the [[Utraquists]] reunited with the Catholic Church, they were able to defeat the Taborites in the [[Battle of Lipany]] in 1434. Sigismund said after the battle that "only the Bohemians could defeat the Bohemians." | ||

| Line 74: | Line 67: | ||

Despite the victory, the Bohemian Utraquists were still in the position to negotiate [[freedom of religion]] in 1436. This happened in the so-called Basel Compacts, declaring peace and freedom between Catholics and Utraquists. It would only last for a short period of time, as [[Pope Pius II]] declared the Basel Compacts to be invalid in 1462. | Despite the victory, the Bohemian Utraquists were still in the position to negotiate [[freedom of religion]] in 1436. This happened in the so-called Basel Compacts, declaring peace and freedom between Catholics and Utraquists. It would only last for a short period of time, as [[Pope Pius II]] declared the Basel Compacts to be invalid in 1462. | ||

| − | In 1458, [[George of Podebrady]] was elected to ascend to the Bohemian throne. He is remembered for his attempt to set up a pan-European "Christian League", which would form all the states of Europe into a community based on religion. In the process of negotiating, he appointed [[Leo of Rozmital]] | + | In 1458, [[George of Podebrady]] was elected to ascend to the Bohemian throne. He is remembered for his attempt to set up a pan-European "Christian League", which would form all the states of Europe into a community based on religion. In the process of negotiating, he appointed [[Leo of Rozmital]] to tour the European courts and to conduct the talks. However, the negotiations were not completed because George's position was substantially damaged over time by his deteriorating relationship with the Pope. |

| − | Jan Zizka, born in 1370, was the commander of the Bohemian military and the head of the anti Hussite forces during the | + | ===Jan Zizka=== |

| + | Jan Zizka, born in 1370, was the commander of the Bohemian military and the head of the anti Hussite forces during the crusades of Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund. In 1410, he fought on the Polish side in the battle that defeated the Teutonic Knights there, but it was not until the outbreak of the Hussite Wars that an opportunity to hone his tactical genius came knocking. The Hussites continued to be a powerhouse in Bohemia and Moravia after the murder of Hus, The Hussite Wars began in 1419, splitting the general Hussite movement into numerous groups. The moderate group was called the Utraquists and consisted of the lesser nobility and the bourgeoiseie. They basically agreed with the Roman Catholic Church. The most radical division of the Hussites was the Taborites, named after their religious center and stronghold at Tabor, which was founded by their credible leader, Jan Zizka. They accepted the doctrines of John Wyclif. This group consisted mainly of peasants and expressed the messianic hopes of the oppressed. Another significant leader that emerged from this class besides Zizka was Procopius the Great. | ||

The Hussite movement ultimately failed, but many aspects of it have become of permanent historical significance. It was the first noteworthy attack on the two strongholds of medieval society, feudalism and the Roman Catholic Church. Not only did it help blaze the path for both the Protestant Reformation and the rise of modern nationalism, but it also brought about new military innovations at the hands of the military mastermind, Jan Zizka. | The Hussite movement ultimately failed, but many aspects of it have become of permanent historical significance. It was the first noteworthy attack on the two strongholds of medieval society, feudalism and the Roman Catholic Church. Not only did it help blaze the path for both the Protestant Reformation and the rise of modern nationalism, but it also brought about new military innovations at the hands of the military mastermind, Jan Zizka. | ||

| Line 86: | Line 80: | ||

Zizka's views and the extreme religious views of the Taborites began to clash, so he formed his own Hussite wing in 1423. Even though it might seem like he distanced himself from his former colleagues, he still remained in close alliance with the Taborites. In that same year, the tension between the extreme Taborites and the conservative Utraquists, whose main-grounds were at Prague, escalated into a full-blown battle. Late in 1424, Zizka led his faithful army against Prague in order to intimidate and influence the people of that city to adhere to his unparalleled anti-Catholic beliefs. A truce between the two Hussite parties shot a much needed blow into the possibility of a civil war. The two factions then decided to partake in a joint expedition into Moravia under Zizka’s command. Suddenly during the campaign, Zizka suffered an untimely death. | Zizka's views and the extreme religious views of the Taborites began to clash, so he formed his own Hussite wing in 1423. Even though it might seem like he distanced himself from his former colleagues, he still remained in close alliance with the Taborites. In that same year, the tension between the extreme Taborites and the conservative Utraquists, whose main-grounds were at Prague, escalated into a full-blown battle. Late in 1424, Zizka led his faithful army against Prague in order to intimidate and influence the people of that city to adhere to his unparalleled anti-Catholic beliefs. A truce between the two Hussite parties shot a much needed blow into the possibility of a civil war. The two factions then decided to partake in a joint expedition into Moravia under Zizka’s command. Suddenly during the campaign, Zizka suffered an untimely death. | ||

| − | + | he is definitely one of the greatest military innovators of all time. Peasants and townspeople, very inexperienced in arms, comprised the brunt of his army. Zizka didn’t dwell on trying to force them to conform to conventional armament and tactics of that time. Instead, he let them make use of crude weapons such as iron-tipped flails and armored farm wagons, which were mounted with small howitzer type cannons. When used for offense, his armored wagons broke through enemy lines with the greatest of ease. The wagons were constantly firing as they advanced, enabling the soldiers to slice through superior forces. The wagons were arranged into an inpenetratable barrier surrounding the foot soldiers when used for defense. They were also used to transport his men. This illustrates how much Zizka played in the anticipation of the principles of modern tank warfare. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Jan Zizka is the epitome of the word commander. Being blind in both eyes would discourage the common man to continue on, but to Zizka this was a minor set back. While leading his troops, he continued to fight and endless battle for what he believed and in the end paid the ultimate price. | Jan Zizka is the epitome of the word commander. Being blind in both eyes would discourage the common man to continue on, but to Zizka this was a minor set back. While leading his troops, he continued to fight and endless battle for what he believed and in the end paid the ultimate price. | ||

| + | He was born to a family of the lower nobility, in the South Bohemian town of Trocnov. The next we hear of him is in 1409, when he joined in an armed gang formed by members of the lower nobility, which held up and robbed members of the merchant class, and took part in minor conflicts between wealthy nobles. Jan Zizka was caught by the authorities. King Wenceslas IV granted him a pardon for his crimes, "Zizka turned up in Czech forces fighting in Poland in 1409 and 1410 against Prussia's Teutonic Knights. The Poles had been involved in a long war against the Teutonic Knights, in order to prevent them from spreading further East. A number of members of the Czech lower nobility fought for the Polish king. Jan Zizka took part in the Battle of Grunwald in 1410, where the Polish army inflicted a heavy defeat on the Teutonic Knights." | ||

| + | Jan Zizka then returned to Prague and became a minor official at the king's court, and also served one of the wealthier nobles at the court. During this time the reform preacher Jan Hus preached regularly at the Bethlehem Chapel. Hus had many followers, but it is not known if Jan Zizka attended any of his sermons, although many people believe that he did. | ||

| − | + | The situation deteriorated between the Hussite reformers and the Catholics, and in June 1419, a Hussite mob threw the city's leading officials out of the window of the Town Hall. People flooded to Prague and began sacking monasteries and churches, attacking the church's wealth. Sigismund, the King of Hungary also became king of the Czech Lands. He was pro-Catholic, and had crusades summoned to remove the Hussite threat from the Czech Lands. The stage was set for the Hussite Wars, which were to last until 1436. It was at this point that Jan Zizka brought up the idea of a proper defence for the Hussites, he moved to South Bohemia, where he helped found the stronghold of Tabor. On his way to Tabor, he was forced to fight Catholic forces at Sudomer: | |

| − | + | "Jan Zizka had women's clothes placed on the bottom of a pond beside his forces, and when the enemy cavalry tried to cross the pond, the horses' hooves got stuck in the clothes. This prevented them from moving, and Zizka's men, who were poorly armed, untrained men, were able to cut these well-trained and well-armed soldiers down." | |

| − | |||

| − | and | ||

| − | |||

| − | and | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Once at Tabor, he was made one of the town's four captains, and he set about training an army of peasants. Trouble loomed in 1420, as a massive and professional army of crusaders, numbering around thirty thousand, from all over Europe arrived in Prague. Jan Zizka took a few hundred of peasants to help defend the city, which was still predominantly pro-Hussite. Jan Zizka had had trenches and walls made to hide and protect his troops, and after a short but bloody battle Zizka's troops, although heavily outnumbered, repulsed the crusaders." | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The army of crusaders broke up and left the country, but other armies or individual war bands came to the Czech Lands followed. Jan Zizka continued to lead the Hussites, but divisions with the movement led him to leave Tabor, which was a centre for radicals, and set up another, more moderate stronghold, called Little Tabor in East Bohemia. He continued to fight with great success, and trained a professional field army. He had carts covered with armour, and filled with troops, making them mobile and more effective than the crusaders, and he even had his horses shoed the wrong way round, to confuse enemy troops as to which way his forces had gone. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The army of crusaders broke up and left the country, but other armies or individual war bands came to the Czech Lands followed. Jan Zizka continued to lead the Hussites, but divisions with the movement led him to leave Tabor, which was a centre for radicals, and set up another, more moderate stronghold, called Little Tabor in East Bohemia. He continued to fight with great success, and trained a professional field army | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Jan Zizka died suddenly of the plague in 1424. His Hussite forces continued to fight successfully until they were torn apart by internal rivalries at the Battle of Lipany in 1436. | Jan Zizka died suddenly of the plague in 1424. His Hussite forces continued to fight successfully until they were torn apart by internal rivalries at the Battle of Lipany in 1436. | ||

Revision as of 09:43, 22 April 2007

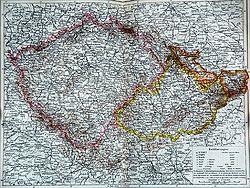

Bohemia (Czech: Čechy; Template:Audio-de) is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western and middle thirds of the Czech Republic. It has an area of 52,750 km² and 6.25 million of the country's 10.3 million inhabitants.

Bohemia is bordered by Germany to the southwest, west, and northwest, Poland to the north-east, the Czech historical region of Moravia to the east, and Austria to the south. Bohemia's borders are marked with mountain ranges such as the Šumava, the Ore Mountains, and the Giant Mountains within the Sudeten mountains.

Note: In the Czech language there is no distinction between adjectives referring to Bohemia and the Czech Republic, i.e. český means both Bohemian and Czech.

History

Ancient Bohemia

The first unequivocal reference to Bohemia dates back to the Roman times, with names such as Boiohaemum, Germanic for "the home of the Boii," a Celtic people. Lying on the crossroads of major Germanic and Slavic tribes during the Migration Period, the area was settled from about 100 B.C.E. by Germanic peoples, including the Marcomanni, who then moved southwest and were replaced around 600 C.E. by the Slavic precursors of today's Czechs.

Přemyslid dynasty

After freeing themselves from the rule of the Avars in the 7th century, Bohemia's Slavic inhabitants came in the 9th century under the rule of the Premyslids, the first historically proven dynasty of Bohemian princes, which lasted until 1306. A legend says that the first Premyslid prince was Premysl Orac, who married Libuse, the founder of Prague, but the first historically documented prince was Borivoj I. The first Premyslid to use the title of King of Bohemia was Boleslav I, after 940, but his successors again assumed the title of duke. The title of king was then granted to Premyslid dukes Vratislav II and Vladislav II in the 11th and 12th centuries, respectively, and became hereditary under Ottokar I in 1198.

With Bohemia's conversion to Christianity in the 9th century, close relations were forged with the East Frankish kingdom, then part of the Carolingian empire and later the nucleus of the Holy Roman Empire, of which Bohemia was an autonomous part from the 10th century on. Under Boleslav II “Pious”, the Premyslid dynasty strengthened its position by founding a bishopric in Prague in 973, thus severing the dependence of the Czech Church on the German Church and opening up the territory for German and Jewish merchant settlements.

At the same time, the powerful House of Slavniks were working to establish a separate duchy in the eastern part of Bohemia – backed by an army and fortresses, and they went on to gain control over more than one-third of Bohemia. In 982, Vojtech of the Slavnik dynasty was appointed Prague bishop and sought separation of the Church and state. His brothers maintained ties with the German ruler and minted their own currency. The Czech lands thus saw concurrent development of two independent states – the of the Premyslids and Slavniks. Boleslav II did not tolerate competition for long and in 995 had all Slavniks murdered, an act that marked the unification of Czech lands.

Ottokar I’s assumption of the throne in 1197 marked the culmination of the Premyslid dynasty and the rule of Bohemia by hereditary kings. In 1212, Roman king Friedrich II affirmed the status of Bohemia as kingdom internationally in a document called the Golden Bula of Sicily. This gave the king a privilege to name bishops and extricated the Czech lands from dependence on Roman rulers. Ottokar I’s grandson Ottokar II, who ruled in 1253–1278, founded a short-lived empire that covered modern Austria.

A crucial event in the history of Czech statehood from the second half of the 11th century proved to be the murder of St. Wenceslav (sv. Václav) and his subsequent status as the prince from heaven and protector of the Czech state, whereas Czech rulers were relegated to the status of its temporary representatives. The son of Premyslid duke Vratislav I, he was raised by his grandmother, Ludmila, and after she was murdered shortly after he inherited the rule, he repudiated his mother Drahomira. Wenceslas facilitated the development of the Church and forged ties with Saxony, away from Bavaria, much to the dislike of his political opposition headed by his younger brother Boleslav I “Terrible”. This brotherly conflict ended in murder, when Boleslav I had his brother murdered in 935 on the occasion of the consecration of a church and took over the reign of the Czech lands. Wenceslas was worshipped as a saint from the 10th century, first in the Czech lands and later in neighboring countries. His life and martyrdom were written into numerous legends, including the “First Old Slavonic Legend” that originated in the 10th century.

The mid-13th century saw the beginning of substantial German immigration as the court sought to replace losses from the brief Mongol invasion of Europe in 1241. The Germans settled primarily along the northern, western, and southern borders of Bohemia, although many lived in towns throughout the kingdom.

Luxembourg dynasty

John

The death of the last Premyslid duke, Wenceslas III (Václav III), sent the Czech dukes to a period of hesitation as to the choice of the Czech king, until they selected John of Luxembourg “Blind”, the son of Friedrich VII, the king of Germany and Roman Empire, in 1310, with condititions, including extensive concessions to the Czech dukes. John married the sister of the last Premyslid but the Czech kingdom was an unexplored territory for him; he did not understand the customs or needs of the country. He ruled as the King of Bohemia in 1310-1346 and the King of Poland in 1310-1335. Being a shrewd politician nicknamed “King Diplomat”, John annexed Upper Silesia and most Silesian duchies to Bohemia, and had his sights set at northern Italy as well. In 1335, he gave up all claims to the Polish throne.

Charles IV

In 1334, John appointed his oldest son Charles IV as the de facto administrator of Czech lands, setting off the period of Luxembourg dual reign, and six years later he safeguarded the Czech crown for him as well as Charles’ endeavors to obtain the Roman kingship, in which Charles succeeded in 1346, still during his father’s life. Charles IV was crowned as the King of Bohemia in 1346 and labored to uplift not only Bohemia but also the rest of Europe. As the Holy Roman Emperor and the Czech king, dubbed the “Father of the Country”, he is the most notable European ruler of the late Middle Ages. In line with the Luxembourg tradition, Charles IV was sent at a very young age to the French court, where he received extensive education and acquired mastery of German, French, Latin, and Italian languages. Czech language was the closest to his heart though, and two years into his election as king, he founded central Europe's first university, Charles University in Prague.

In 1355, Charles IV ascended to the Roman throne, and a year later he issued the Golden bula of Charles IV, a set of statutes to be valid in the Holy Roman Empire until 1806. His reign brought Bohemia to its peak both in terms of policy and territory; the Bohemian crown controlled such diverse lands as Moravia, Silesia, Upper Lusatia and Lower Lusatia, Brandenburg, an area around Nuremberg called New Bohemia, Luxembourg, and several small towns scattered around Germany. On the home turf, he triggered an unprecedented economic, cultural and artistic boom in Prague and the rest of Bohemia. On the home turf, he triggered an unprecedented economic, cultural and artistic boom in Bohemia, refusing to move to Rome and instituting Prague as the imperial capital. Construction in Prague was in the full swing, and many sights bear his name. The Prague Castle and much of the Saint Vitus Cathedral were completed under his patronage. The Czech Republic labels him Father of the Country (Pater patriae in Latin), a title first coined at his funeral. His imperial policy was focused on the economic and intellectual development of Bohemia; he corresponded with Petrarch, the initiator of Renaissance Humanism, who hoped in vain that Charles IV would transfer the capital of the Holy Roman Empire from Prague to Rome and renew the glory of the Empire.

Sigismund

Charles IV’s son Emperor Sigismund of Luxemburg, the last of the House of Luxembourg on the Czech throne, as well as the King of Hungary and Holy Roman Emperor, has left behind a legacy of contradictions. He lost the Polish crown in 1384 but gained the Hungarian crown in 1387. In an effort to secure the Dalmatian coast under his reign, he organized a crusade but was defeated by the Osman Turks. After internment by the Hungarian nobility in 1401, he refocused his efforts on Bohemia and lent his support to the higher nobility fighting his step-brother, King Wenceslas IV, whom he later took hostage and transferred to Vienna for over a year. As an administrator of the Czech Kingdom appointed by Wenceslas IV, he took over the Czech crown. After the brothers’ reconciliation in 1404, Sigismund returned to Hungary, where he calmed down political turbulences and initiated an economic and cultural boom, granting privileges to cities, which he considered as the cornerstone of his rule. He also considered the Church subordinate to secular rule, and in 1403-1404, after disputes with the pope, he banned monetary appropriations for the Church and manned bishoprics and other religious institutions.

As a Roman king, Sigismund sought to reform the Roman Church and settle the papal schism, a token of which was the convening of the Council of Constance in 1415, the rector of Charles University and a prominent reformer and religious thinker Jan Hus was sentenced to be burned at the stake as a heretic, with the king’s undeniable involvement. Hus was invited to attend the council to defend himself and the Czech positions in the religious court, but with the emperor's approval, he was executed on July 6, 1415. His execution of Hus, as well as a papal crusade against the Hussites and John Wycliffe, outraged the Czechs. Their ensuing rebellion against Romanists became known as the Hussite Wars.

Although a natural successor to Wenceslas IV, as a Czech king, Sigismund, who inherited the Czech throne in 1420, grappled with defiance from the Hussites, whom he unsuccessfully sought to subdue in repeated crusades. Only in 1436, after he agreed to reconciliatory terms between the Hussites and the Catholic Church, was he recognized as the Czech king. One year later he died.

Hussite Bohemia

You who are warriors of God and his law. Ask God for help and hope in him that in his name you may gloriously triumph. (Hussite battle hymn)

The largely peasant uprising against imperial forces was led by a former mercenary, Jan Žižka of Trocnov. As the leader of the Hussite armies, he utilized innovative tactics and weapons, such as howitzers, pistols (from Czech píšťala, the flute), and fortified wagons, which were revolutionary for the time and established Žižka as a great general.

After Žižka's death, Prokop the Great took over the command for the army, and under his lead the Hussites were victorious for another ten years, to the sheer terror of Europe. The Hussite cause gradually splintered into two main factions, the moderate Utraquists and the more fanatic Taborites. After the Utraquists reunited with the Catholic Church, they were able to defeat the Taborites in the Battle of Lipany in 1434. Sigismund said after the battle that "only the Bohemians could defeat the Bohemians."

Despite the victory, the Bohemian Utraquists were still in the position to negotiate freedom of religion in 1436. This happened in the so-called Basel Compacts, declaring peace and freedom between Catholics and Utraquists. It would only last for a short period of time, as Pope Pius II declared the Basel Compacts to be invalid in 1462.

In 1458, George of Podebrady was elected to ascend to the Bohemian throne. He is remembered for his attempt to set up a pan-European "Christian League", which would form all the states of Europe into a community based on religion. In the process of negotiating, he appointed Leo of Rozmital to tour the European courts and to conduct the talks. However, the negotiations were not completed because George's position was substantially damaged over time by his deteriorating relationship with the Pope.

Jan Zizka

Jan Zizka, born in 1370, was the commander of the Bohemian military and the head of the anti Hussite forces during the crusades of Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund. In 1410, he fought on the Polish side in the battle that defeated the Teutonic Knights there, but it was not until the outbreak of the Hussite Wars that an opportunity to hone his tactical genius came knocking. The Hussites continued to be a powerhouse in Bohemia and Moravia after the murder of Hus, The Hussite Wars began in 1419, splitting the general Hussite movement into numerous groups. The moderate group was called the Utraquists and consisted of the lesser nobility and the bourgeoiseie. They basically agreed with the Roman Catholic Church. The most radical division of the Hussites was the Taborites, named after their religious center and stronghold at Tabor, which was founded by their credible leader, Jan Zizka. They accepted the doctrines of John Wyclif. This group consisted mainly of peasants and expressed the messianic hopes of the oppressed. Another significant leader that emerged from this class besides Zizka was Procopius the Great.

The Hussite movement ultimately failed, but many aspects of it have become of permanent historical significance. It was the first noteworthy attack on the two strongholds of medieval society, feudalism and the Roman Catholic Church. Not only did it help blaze the path for both the Protestant Reformation and the rise of modern nationalism, but it also brought about new military innovations at the hands of the military mastermind, Jan Zizka.

When the Hussite Wars ignited in 1420, Zizka was nearly sixty years old and already blind in one eye. Soon after joining the Taborites, he made Tabor in Bohemia into a fortress that was nearly impossible to bring down. In July of 1420, he led the Taborite troops in their startling victory over Sigismund at Vysehrad, now a part of Prague. Sigismund was the pro-Catholic king of Hungary and successor to the Bohemian throne after the King of Wenceslas in1419. He failed miserably in repeated attempts to gain control of the Hussite kingdom. He was even was aided by the Hungarian and German armies.

Overseen by the Czech yeoman Zizka, riots broke out and led to the invasion and overhaul of the Hussite kingdom. Zizka’s armies then spread over the countryside, storming monastaries and innocent villages. In the following years, Zizka courageously withstood the force of the anti-Hussite crusades and continued to dominate one Catholic stronghold after another. He stubbornly kept commanding in person, even though he had become completely blind by 1421.

Zizka's views and the extreme religious views of the Taborites began to clash, so he formed his own Hussite wing in 1423. Even though it might seem like he distanced himself from his former colleagues, he still remained in close alliance with the Taborites. In that same year, the tension between the extreme Taborites and the conservative Utraquists, whose main-grounds were at Prague, escalated into a full-blown battle. Late in 1424, Zizka led his faithful army against Prague in order to intimidate and influence the people of that city to adhere to his unparalleled anti-Catholic beliefs. A truce between the two Hussite parties shot a much needed blow into the possibility of a civil war. The two factions then decided to partake in a joint expedition into Moravia under Zizka’s command. Suddenly during the campaign, Zizka suffered an untimely death.

he is definitely one of the greatest military innovators of all time. Peasants and townspeople, very inexperienced in arms, comprised the brunt of his army. Zizka didn’t dwell on trying to force them to conform to conventional armament and tactics of that time. Instead, he let them make use of crude weapons such as iron-tipped flails and armored farm wagons, which were mounted with small howitzer type cannons. When used for offense, his armored wagons broke through enemy lines with the greatest of ease. The wagons were constantly firing as they advanced, enabling the soldiers to slice through superior forces. The wagons were arranged into an inpenetratable barrier surrounding the foot soldiers when used for defense. They were also used to transport his men. This illustrates how much Zizka played in the anticipation of the principles of modern tank warfare.

Jan Zizka is the epitome of the word commander. Being blind in both eyes would discourage the common man to continue on, but to Zizka this was a minor set back. While leading his troops, he continued to fight and endless battle for what he believed and in the end paid the ultimate price.

He was born to a family of the lower nobility, in the South Bohemian town of Trocnov. The next we hear of him is in 1409, when he joined in an armed gang formed by members of the lower nobility, which held up and robbed members of the merchant class, and took part in minor conflicts between wealthy nobles. Jan Zizka was caught by the authorities. King Wenceslas IV granted him a pardon for his crimes, "Zizka turned up in Czech forces fighting in Poland in 1409 and 1410 against Prussia's Teutonic Knights. The Poles had been involved in a long war against the Teutonic Knights, in order to prevent them from spreading further East. A number of members of the Czech lower nobility fought for the Polish king. Jan Zizka took part in the Battle of Grunwald in 1410, where the Polish army inflicted a heavy defeat on the Teutonic Knights." Jan Zizka then returned to Prague and became a minor official at the king's court, and also served one of the wealthier nobles at the court. During this time the reform preacher Jan Hus preached regularly at the Bethlehem Chapel. Hus had many followers, but it is not known if Jan Zizka attended any of his sermons, although many people believe that he did.

The situation deteriorated between the Hussite reformers and the Catholics, and in June 1419, a Hussite mob threw the city's leading officials out of the window of the Town Hall. People flooded to Prague and began sacking monasteries and churches, attacking the church's wealth. Sigismund, the King of Hungary also became king of the Czech Lands. He was pro-Catholic, and had crusades summoned to remove the Hussite threat from the Czech Lands. The stage was set for the Hussite Wars, which were to last until 1436. It was at this point that Jan Zizka brought up the idea of a proper defence for the Hussites, he moved to South Bohemia, where he helped found the stronghold of Tabor. On his way to Tabor, he was forced to fight Catholic forces at Sudomer: "Jan Zizka had women's clothes placed on the bottom of a pond beside his forces, and when the enemy cavalry tried to cross the pond, the horses' hooves got stuck in the clothes. This prevented them from moving, and Zizka's men, who were poorly armed, untrained men, were able to cut these well-trained and well-armed soldiers down."

Once at Tabor, he was made one of the town's four captains, and he set about training an army of peasants. Trouble loomed in 1420, as a massive and professional army of crusaders, numbering around thirty thousand, from all over Europe arrived in Prague. Jan Zizka took a few hundred of peasants to help defend the city, which was still predominantly pro-Hussite. Jan Zizka had had trenches and walls made to hide and protect his troops, and after a short but bloody battle Zizka's troops, although heavily outnumbered, repulsed the crusaders."

The army of crusaders broke up and left the country, but other armies or individual war bands came to the Czech Lands followed. Jan Zizka continued to lead the Hussites, but divisions with the movement led him to leave Tabor, which was a centre for radicals, and set up another, more moderate stronghold, called Little Tabor in East Bohemia. He continued to fight with great success, and trained a professional field army. He had carts covered with armour, and filled with troops, making them mobile and more effective than the crusaders, and he even had his horses shoed the wrong way round, to confuse enemy troops as to which way his forces had gone. Jan Zizka died suddenly of the plague in 1424. His Hussite forces continued to fight successfully until they were torn apart by internal rivalries at the Battle of Lipany in 1436.

Habsburg Monarchy

After the death of King Louis II of Hungary and Bohemia in the Battle of Mohács in 1526, Archduke Ferdinand of Austria became King of Bohemia and the country became a constituent state of the Habsburg Monarchy.

Bohemia enjoyed religious freedom between 1436 and 1620, and became one of the most liberal countries of the Christian world during that period of time. In 1609 King Rudolph II, himself a Roman Catholic, was moved by the Bohemian nobility to publish Maiestas Rudolphina, which confirmed the older Confessio Bohemica of 1575.

After King Ferdinand II began oppressing the rights of Protestants in Bohemia, the resulting Czech rebellion resulted in the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War in 1618. Elector Frederick V of the Palatinate, a Protestant, was elected by the Bohemian nobility to replace Ferdinand on the Bohemian throne. However, after Frederick's defeat in the Battle of White Mountain in 1620, a few Protestant noblemen were executed and the rest were exiled from the country; their lands were then given to Catholic loyalists.

Until the so-called "renewed constitution" of 1627, the German language was established as a second official language in the Czech lands. The Czech language remained the first language in the kingdom. Both German and Latin were widely spoken among the ruling classes, although German became increasingly dominant, while Czech was spoken in much of the countryside.

The formal independence of Bohemia was further jeopardized when the Bohemian Diet approved administrative reform in 1749. It included the indivisibility of the Habsburg Empire and the centralization of rule; this essentially meant the merging of the Royal Bohemian Chancellery with the Austrian Chancellery.

At the end of the 18th century, the Czech national revivalist movement, in cooperation with part of the Bohemian aristocracy, started a campaign for restoration of the kingdom's historic rights, whereby the Czech language was to replace German as the language of administration. The enlightened absolutism of Joseph II and Leopold II, who introduced minor language concessions, showed promise for the Czech movement, but many of these reforms were later rescinded. During the Revolution of 1848, many Czech nationalists called for autonomy for Bohemia from Habsburg Austria, but the revolutionaries were defeated. The old Bohemian Diet, one of the last remnants of the independence, was dissolved, although the Czech language experienced a rebirth as romantic nationalism developed among the Czechs.

In 1861, a new elected Bohemian Diet was established. The renewal of the old Bohemian Crown (Kingdom of Bohemia, Margraviate of Moravia, and Duchy of Silesia) became the official political program of both Czech liberal politicians and the majority of Bohemian aristocracy ("state rights program"), while parties representing the German minority and small part of the aristocracy proclaimed their loyalty to the centralistic Constitution (so-called "Verfassungstreue"). After the defeat of Austria in the Austro-Prussian War in 1866, Hungarian politicians achieved the Ausgleich (compromise) which created Austria-Hungary in 1867, ostensibly creating equality between the Austrian and Hungarian halves of the empire. An attempt of the Czechs to create a tripartite monarchy (Austria-Hungary-Bohemia) failed in 1871. However, the "state rights program" remained the official platform of all Czech political parties (except for social democrats) until 1918.

20th century

After World War I, Bohemia became the core of the newly-formed country of Czechoslovakia, which combined Bohemia, Moravia, Austrian Silesia, and the Northern parts (Highlands) of Hungary into one state. Under its first president, Tomáš Masaryk, Czechoslovakia became a rich and liberal democratic republic.

Following the Munich Agreement in 1938, the border regions of Bohemia inhabited predominantly by ethnic Germans (the Sudetenland) were annexed to Nazi Germany; this was the single time in Bohemian history that its territory was divided. The remnants of Bohemia and Moravia were then annexed by Germany in 1939, while the Slovak lands became Slovakia. From 1939–1945 Bohemia (without the Sudetenland) formed with Moravia the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (Reichsprotektorat Böhmen und Mähren). After World War II ended in 1945, the vast majority of remaining Germans were expelled through the Beneš decrees.

Beginning in 1949, Bohemia ceased to be an administrative unit of Czechoslovakia, as the country was divided into kraje. In 1989 Agnes of Bohemia became the first saint from a Central European country to be canonized by Pope John Paul II before the "Velvet Revolution" later that year. After the dissolution of Czechoslovakia in 1993 (the "Velvet Divorce"), the territory of Bohemia became part of the new Czech Republic.

The Czech constitution from 1992 refers to the "citizens of the Czech Republic in Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia" and proclaims continuity with the statehood of the Bohemian Crown. Bohemia is not currently an administrative unit of the Czech Republic. Instead, it is divided into the Prague, Central Bohemian, Plzeň, Karlovy Vary, Ústí nad Labem, Liberec, and Hradec Králové Regions, as well as parts of the Pardubice, Vysočina, South Bohemian and South Moravian Regions.

See also

- History of Bohemia

- History of the Czech lands

- List of rulers of Bohemia

- Sudetenland

- German Bohemia

- Bohemia

Template:HRE electors

| ||||||||||||

Footnotes

Sources and Further Reading

- Sayer,Derek , The coasts of Bohemia: a Czech history, Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press, 1998, ISBN 0691057605 - ISBN 9780691057606

- Freeling,Nicolas , The Seacoast of Bohemia, New York, Mysterious Press, 1995, ISBN 089296555X - ISBN 9780892965557 OCLC: 31754195

- Teich, Mikuláš, Bohemia in History, Cambridge, U.K.; New York, NY, Cambridge University Press, 1998, ISBN 0521431557 OCLC: 37211187

- Oman, Carola, The Winter Queen: Elizabeth of Bohemia, London; Phoenix, 2000, ISBN 1842120573 OCLC: 43879234

External Links

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_IV,_Holy_Roman_Emperor http://www.sweb.cz/royal-history/premysl.html http://dejepis.info/?t=94 Vrcholní Přemyslovci na českém trůně, královský titul jako dědičný, vrcholné období středověkých českých dějin http://www.oa.svitavy.cz/pro/renata/dejiny/z8109/preot.htm Pøemysl I. Otakar http://cr.ic.cz/index.php?clanek=slavnik&dir=premyslovci&menu=premyslovci Boleslav II. a Slavníkovci historie ceske republiky http://cr.ic.cz/index.php?clanek=povesti&dir=povesti&menu=povesti http://zivotopisyonline.cz/svaty-vaclav.php svatý Václav (?907-28.9.929/35) "Světec a patron českých zemí" http://cr.ic.cz/index.php?clanek=lucemburk&dir=lucemburk&menu=lucemburk Lucemburkové na českém trůnu http://zivotopisyonline.cz/jan-lucembursky-slepy.php Jan Lucemburský Slepý (10.8.1296 - 26.8. 1346) "Otec Karla IV." http://zivotopisyonline.cz/karel-ctvrty-lucembursky.php Karel IV. Lucemburský (14.5.1316-29.11.1378) "Otec vlasti" http://zivotopisyonline.cz/zikmund-lucembursky.php Zikmund Lucemburský (14.2.1368-9.12.1437) "Liška ryšavá?" http://www.hotelpraguecity.com/fotky/okoli/zizka2.html Jan Zizka: The Blind General http://www.radio.cz/en/article/37448 Jan Zizka [23-02-2000] By Nick Carey

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.