Difference between revisions of "Blue Nile" - New World Encyclopedia

Vicki Phelps (talk | contribs) |

Vicki Phelps (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

The aim is an 11fold increase in capacity to 9,000 megawatts by 2018 with surplus power exported to neighboring Kenya, Djibouti, and Sudan. | The aim is an 11fold increase in capacity to 9,000 megawatts by 2018 with surplus power exported to neighboring Kenya, Djibouti, and Sudan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Ethiopian Electric Power Corporation said power supply coverage has increased to 22 per cent now from less than 10 per cent 17 years ago because of the victory achieved on May 28. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Public Relations Manager Sendeku Araya told ENA on Monday that the country's power capacity which was 300 mega watts before 1984 has now reached to 800 mega watt. Sendeku Araya | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sendeku made the statement in connection with May 28, a day marking the demise of the Derg Regime. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The number of benefiting towns and villages in the country that stood at only 410 before the May 28, 1991 victory, which was 36 years after the establishment of the sector, has now reached to 1,752, the Manager added. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sendeku said the number of beneficiaries went to over one million now from 460,000 during the reported period. | ||

== Exploration == | == Exploration == | ||

Revision as of 16:33, 10 September 2008

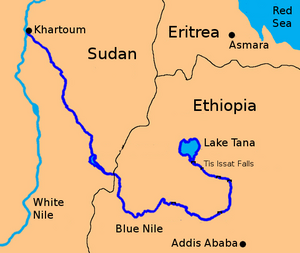

The Blue Nile is a river originating at Lake Tana in Ethiopia. Sometimes in Ethiopia the river—especially the upper reaches—is called the Abbai.

The Abbai portion of the river is considered holy by many in Ethiopia and is believed to be the Gihon river mentioned as flowing out of the Garden of Eden in Genesis 2.[1] The Abbai portion of the Blue Nile rises at Lake Tana and flows for some 19 miles (30 km) before plunging over the Tis Issat Falls. The river then loops across northwest Ethiopia through a series of deep valleys and canyons into Sudan, by which point it is only known as the Blue Nile.

The annual flood in Egypt is a gift of the annual monsoon in Ethiopia. In the winter, when little rain falls in the highlands, the Blue Nile/Atbara rivers dry up. In the summer, moist winds from the Indian Ocean cool as they climb up the Ethiopian highlands, bringing torrential rains that fill the dry washes and canyons with rushing water that ultimately joins the Blue Nile or the Atbara.

Although there are several feeder streams that flow into Lake Tana, the sacred source of the river is generally considered to be a small spring at Gish Abbai at an altitude of approximately 5,940 feet (1,800 m). The Blue Nile much later joins the White Nile at Khartoum, Sudan, and, as the Nile, flows through Egypt to the Mediterranean Sea at Alexandria. The Blue Nile is so-called because during flood times the water current is so high that it changes color to almost black; in the local Sudanese language the word for black is also used for blue.

The distance from its source to its confluence is variously reported as 907 and 1,000 miles (1,460 and 1,600 km). The uncertainty over its length might partially result from the fact that it flows through virtually impenetrable gorges cut in the Ethiopian highlands to a depth of some 4,950 feet (1,500 m)—a depth comparable to that of the Grand Canyon in the United States.

The Blue Nile flows generally south from Lake Tana and then west across Ethiopia and northwest into Sudan. Within 18.6 miles (30 km) of its source at Lake Tana, the river enters a canyon about 400 km long. This gorge is a tremendous obstacle for travel and communication from the north half of Ethiopia to the southern half. The power of the Blue Nile may best be appreciated at Tis Issat Falls, which are 148 feet (45 m) high. Despite the hazards and obstacles of the river, on January 29, 2005, Canadian Les Jickling and New Zealander Mark Tanner reached the Mediterranean Sea after an epic 148- day journey, becoming the first to have paddled the Blue Nile from source to sea.

The flow of the Blue Nile reaches maximum volume in the rainy season (from June to September), when it supplies about two-thirds of the water of the Nile proper. The Blue Nile, along with the Atbara River to the north, which also flows out of the Ethiopian highlands, were responsible for the annual Nile floods that contributed to the fertility of the Nile Valley and the consequent rise of ancient Egyptian civilization and Egyptian mythology. With the completion in 1970 of the Aswan High Dam in Egypt, the Nile floods ended.

Economy

The Blue Nile is vital to the livelihood of Egypt. Though shorter than the White Nile, 56 percent of the water that reaches Egypt originates from the Blue Nile branch of the great river; when combined with the Atbara River, which also has its source in the Ethiopian highlands, the figure rises to 90 percent of the water and 96 percent of transported sediment.

The river is also an important resource for Sudan, where the Roseires and Sennar dams produce 80 percent of the country's power. These dams also help irrigate the Gezira Plain, which is most famous for its high quality cotton. The region also produces wheat and animal feed crops.

The Tis Issat or Blue Nile Falls consist of four streams that originally varied from a trickle in the dry season to over 400 meters wide in the rainy season. Regulation of Lake Tana now reduces the variation somewhat, and since 2003 a hydro-electric station has taken much of the flow out of the falls except during the rainy season.[2] It was considered one of Ethiopia's best-known tourist attractions, but in recent years almost no water comes over the falls due to the new hydropower plant.

Ethiopia has one of the lowest levels of energy consumption per capita in the world; only about 15 percent of the population has access to electricity. Electric supply is under the Ethiopian Electric Power Corporation (EEPCo). The state owned company currently provides electricity to over 777,007 customers in approximately 632 towns and communities in Ethiopia which is only a small proportion of the country's over 70 million inhabitants. (Information from EEPCo website- Accessed September 2008March, 2006).

Ethiopia's Power Sector Development Program

Ethiopia has crafted a comprehensive energy policy prioritizing the expansion and the development and utilization of hydro power. These energy policy measures in the electric power sub-sector are to build national capacity in engineering, construction, operation, and maintenance and gradually enhance local manufacturing capability of electrical equipment and appliances.

Ethiopia is building five hydropower dams by 2011 with a total generating capacity of 3,150 megawatts and is considering spending 3,2 billion euros (US$4,7 billion) on four more, Lemma said.

The aim is an 11fold increase in capacity to 9,000 megawatts by 2018 with surplus power exported to neighboring Kenya, Djibouti, and Sudan.

The Ethiopian Electric Power Corporation said power supply coverage has increased to 22 per cent now from less than 10 per cent 17 years ago because of the victory achieved on May 28.

Public Relations Manager Sendeku Araya told ENA on Monday that the country's power capacity which was 300 mega watts before 1984 has now reached to 800 mega watt. Sendeku Araya

Sendeku made the statement in connection with May 28, a day marking the demise of the Derg Regime.

The number of benefiting towns and villages in the country that stood at only 410 before the May 28, 1991 victory, which was 36 years after the establishment of the sector, has now reached to 1,752, the Manager added.

Sendeku said the number of beneficiaries went to over one million now from 460,000 during the reported period.

Exploration

It is generally believed that the first European to have seen the Blue Nile in Ethiopia was Pedro Paez, a Spanish Jesuit who traveled to the area in the early 1600s; however, John Bermudez provided the first description of the Tis Issat Falls in his memoirs (published in 1565), and a number of Europeans who lived in Ethiopia in the late fifteenth century like Pero da Covilhã could have seen the river before Paez.

Although a number of European explorers contemplated tracing the course of the Blue Nile from its confluence with the White Nile to Lake Tana, its gorge, which begins a few miles inside the Ethiopian border, has discouraged all attempts since Frédéric Cailliaud's attempt in 1821. The first serious attempt by a non-local to explore this reach of the river was undertaken by the American W.W. Macmillan in 1902, assisted by the Norwegian explorer B.H. Jenssen; Jenssen would proceed upriver from Khartoum while Macmillan sailed downstream from Lake Tana. However Jenssen's boats were blocked by the rapids at Famaka short of the Sudan-Ethiopian border, and Macmillan's boats were wrecked shortly after they had been launched. Macmilan encouraged Jenssen to try to sail upstream from Khartoum again in 1905, but he was forced to stop 300 miles short of Lake Tana. The British consul R E Cheesman managed to map the upper course of the Blue Nile between 1925 and 1933, but instead of following the course of the river and its impassible canyon, he mapped it from the highlands above, traveling some 5,000 miles by mule in the adjacent country.[3]

On April 28, 2004, geologist Pasquale Scaturro and his partner, kayaker and documentary filmmaker Gordon Brown, became the first people to navigate the Blue Nile. Though their expedition included a number of others, Brown and Scaturro were the only ones to remain on the expedition for the entire journey. They chronicled their adventure with an IMAX camera and two handheld video cams, sharing their story in the IMAX film Mystery of the Nile and in a book of the same title.[4] Despite this attempt, the team was forced to use outboard motors for most of their journey, and it was not until January 29, 2005, when Canadian Les Jickling and New Zealander Mark Tanner reached the Mediterranean Sea, that the river had been paddled for the first time under human power.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Edward Ullendorff, Ethiopia and the Bible (Oxford: University Press for the British Academy, 1968), p. 2.

- ↑ Matt Philips and Jean-Bernard Carillet, Ethiopia and Eritrea, third edition (n.p.: Lonely Planet, 2006), p. 118

- ↑ Alan Moorehead, The Blue Nile, revised edition (New York: Harper and Row, 1972), pp. 319f

- ↑ Richard Bangs and Pasquale Scaturro, Mystery of the Nile. New York: New American Library, 2005

External links

- The Tana Project

- The Blue Nile Falls

- Rafting Down the Blue Nile

- Paddling the Blue Nile

- International Food Policy Research Institute [1]

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.