Difference between revisions of "Apollinarism" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (37 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ready}} | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Images OK}}{{ready}}{{approved}} |

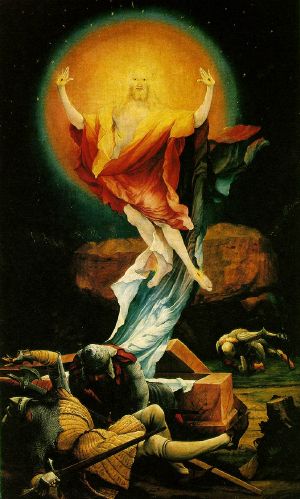

| + | [[Image:Grunewald - christ.jpg|thumb|Christ in his majesty. Was Jesus God, and if so, how could he still be human?]] | ||

| + | '''Apollinarism''' or '''Apollinarianism''' was a view proposed by [[Apollinaris of Laodicea]] (d. 390 C.E.) that [[Jesus]] had a [[human]] body and lower soul (the seat of the emotions) but a [[God|divine]] mind. It arose after the doctrine of the [[Trinity]] had been systematically formulated in 325 at the [[Council of Nicea]], but debate continued about exactly what it meant. Apollinarism was declared to be a [[heresy]] in 381 by the [[First Council of Constantinople]]. | ||

| − | + | Apollianris had developed a solid reputation as a Christian theologian who supported Nicene orthodoxy and courageously defended the Christian faith during the time of [[Julian the Apostate]]. His [[christology|christological]] formula attempted to solve a logical problem which many Christians had in understanding the Nicene formula; namely, "how could Jesus be 'true God' without losing his humanity?" Apollinaris sought to deal with this problem by saying that Jesus retained a human body and feelings, while his mind was the mind of the [[Divine Logos]]. | |

| − | + | His ideas were widely popular but ran into stiff criticism from other church leaders, who accused Apollinaris of dividing Christ into artificial parts—making him less than fully divine and more than truly human at the same time—and thus falling into [[heresy]]. | |

| − | [[ | + | Apollinaris refused to recant his views and persisted in teaching them until his death. After this, his movement persisted for some time, but eventually faded. While some of his followers returned to [[orthodoxy]], others would find a home in the later [[christology|christological movements]] which addressed the problem he tried to solve: [[Monophysitism]], [[Monothelitism]], and [[Nestorianism]]. The [[Council of Chalcedon]] ultimately resolved the issue in 451, although Christians today still grapple with the seeming logical inconsistencies of the "mystery" of the Trinity and the [[Incarnation]]. |

| − | |||

==The career of Appolinaris== | ==The career of Appolinaris== | ||

| − | + | Apollinaris (Apolinarios) was a [[bishop]] of the ancient and prestigious church at [[Laodicea]]. He flourished in the latter half of the fourth century and was at first highly esteemed by men such as [[Athanasius of Alexandria]], [[Basil the Great]], and [[Saint Jerome]], due to his classical and biblical learning, his defense of Christianity against paganism during the reign of [[Julian the Apostate]], and his loyalty to the Nicene faith. He assisted his father, Apollinaris the Elder, in popularizing Christian ideas through Greek literary genres. Together they translated the [[Pentateuch]] into Greek [[hexameter]]s, converted the first two [[books of Kings]] into an [[epic poem]] of 24 cantos, and expressed biblical stories through comedic and tragic [[drama]]s. Jerome credits him with many volumes on the scriptures, including two apologies on behalf of Christianity and a refutation of the Arian teacher [[Eunomius]]. | |

| − | The precise time at which Apollinaris began to promulgate the theory which bears his name is uncertain. However, there are apparently two periods in the Apollinarist controversy. Up to 376, Apollinaris' name was never mentioned by his | + | The precise time at which Apollinaris began to promulgate the theory which bears his name is uncertain. However, there are apparently two periods in the Apollinarist controversy. Up to 376, although the teaching itself was condemned, Apollinaris' name was never mentioned by his opponents, including Athanasius and [[Pope Damasus]]. Nor was he directly criticized in church councils such as that of [[Alexandria]] (362), and Rome (376). However, from 376 onward, open and personal theological [[warfare]] broke out between him and his critics. |

| − | Two late Roman councils, in 377 and 381 plainly | + | Two late Roman councils, in 377 and 381, plainly denounced and condemned the views of Apollinaris as heretical. More importantly, his views were solemnly [[anathema]]tized at the ecumenical [[First Council of Constantinople]] in 381. Indeed, the first act of this synod entered Apollinarism on the list of heresies. Still convinced that he was not in error, he died about 392. |

==The movement of Apollinarism== | ==The movement of Apollinarism== | ||

| − | Apollinarism had considerable in [[Constantinople]], Syria, and Phoenicia. However, after his death, the movement dissipated. Some of his disciples, such as Vitalis, Valentinus, Polemon, and Timothy, tried to perpetuate the teachings of | + | Apollinarism had a considerable following in [[Constantinople]], [[Syria]], and [[Phoenicia]] among Christians who grappled with the issues underlying the [[Council of Nicea]]. However, after his death, the movement eventually dissipated. Some of his disciples, such as Vitalis, Valentinus, Polemon, and Timothy, tried to perpetuate the teachings of their master and may be responsible for several of pseudonymous writings to that end. A contemporary but anonymous book: ''Adversus fraudes Apollinaristarum'', claims that the Apollinarians, in order to win credence for their teaching, circulated a number of tracts under the names of such famous churchmen as [[Gregory Thaumaturgus]] (''He kata meros pistis'', Exposition of Faith), Athanasius (''Peri sarkoseos'', On the Incarnation), Pope Julius (''Peri tes en Christo enotetos'', On Unity in Christ), etc. Some of these works still appear under their supposed authors' names in collections of their works. |

| − | The sect | + | The sect, as such, soon became extinct. By 416, many had returned to the orthodox church, while others drifted into [[Monophysitism]] and other similar theories. |

==Doctrine== | ==Doctrine== | ||

| − | Apollinaris based his theory on two principles, one objective, and one psychological or subjective | + | Apollinaris based his theory on two principles, one objective, and one psychological or subjective. |

| − | + | Objectively, it appeared to him that the union of "true God" with "true man"—the Nicene formula—contained a logical inconsistency, combining two things which could not logically be combined. Two perfect beings with all their attributes, he argued, cannot be completely one, especially when one is infinite and purely spiritual while the other is finite and partly physical. They are at most a compound. To make them absolutely one is not unlike the description of [[demigod]]s in [[Greek mythology]]. However, Apollinaris was careful to affirm that he accepted the Nicene faith, which forbade describing [[God the Son]] as anything less than the "same substance" with the Father. Indeed, he was a harsh critic of the [[Arianism|Arian]] theology which the Council of Nicea condemned for failing to affirm this. | |

| − | Though this formula, the | + | Apollinaris attempted to solve the problem by affirming the complete unity of substance between the mind of Jesus and the mind of God. It was in this sense, he said, that Jesus and God were of the "same substance." However, he also affirmed that Jesus' body and feelings were basically human and not completely divine. Thus, Jesus remained both truly human and truly divine, but his human functions were separated from one another. |

| + | |||

| + | Apollinaris' conscience would not allow him to affirm Christ's [[impeccability]]—his absolute sinlessness—except by affirming that the mind of Jesus' was completely identified with the Divine [[Logos]]. Apollinaris appealed to the well-known Platonic division of human nature: body (sarx, soma), lower soul (psyche, halogos), spirit or mind (nous, pneuma, rational soul). Christ, he said, assumed a human body and a human lower soul, but his mind (or rational soul) was the mind of God. In other words, the Logos—the rational soul of God the Son—takes the place of the human mind in Jesus. In this way, God became the rational and spiritual center, the seat of self-consciousness and self-determination, in Jesus Christ. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Though this formula, the Apollinaris sought to save Nicene Christianity from the logical paradox that so many have seen in it. At the same time he hoped to preserve the unity of Christ himself, seeing him not as two things (completely God and completely man at the same time) but one thing (a man with the mind of God). For scriptural confirmation, he quoted from the Gospel John 1:14 ("and the Word was made flesh"), Philemon 2:7 ("Being made in the likeness of men and in habit found as a man"), and I Cor.15:47 (the second man, from heaven, heavenly"). | ||

==Condemnations== | ==Condemnations== | ||

| + | In answering the challenge of Apollinaris, the orthodox [[Church Fathers]] of his day had not yet evolved the [[christology|christological formulas]] promulgated by the Councils of Ephesus and Chalcedon, which expressed that Christ's human and divine natures were equally present in his person, "without confusion or division." [[Theodoret]] of Cyrrhus charged Apollinaris with confusing the persons of the [[Godhead (Christianity)|Godhead]], and with giving in to the earlier heretical ways of [[Sabellius]]. [[Basil]] accused him of abandoning the literal sense of the scripture, and taking up wholly with the [[allegoricalism|allegorical]] sense. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Generally, his critics posited the following arguments: | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Scripture holds that the Logos assumed ''all'' that is human in Jesus. The only exception to this is that there was no sin in Christ, as in other humans. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Christ without a human rational soul, having the mind only of God, is not truly a man. Such a being can neither be called God-man nor stand as the model of Christian life. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Saintdamasus.png|thumb|150px|Pope Damasus I condemned Apollinarius for teaching that the Logos had replaced the human mind of Jesus.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | *If Christ does not possess a human mind, then this mind is unaffected by his atonement. Thus, the noblest portion of man, his mind (rational soul), is excluded from redemption. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Apollinaris' orthodox critics also pointed out the "correct" meaning of the scriptural passages. Some of them even insisted upon the limitations of Jesus' knowledge as proof positive that his mind was truly human. When Apollinaris sought to draw them into debates about the mystery of the unity of Christ (as both God and man) they often acknowledged their ignorance and derided Apollinaris' insistence on mathematical logic and his implicit reliance upon merely human reasoning. God's ways, they pointed out, are higher than ours, after all. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Eventually, the condemnations reached beyond local bishops and councils to the pope and an [[ecumenical council]]. The following condemnation of Apollinarism is found in the seventh [[anathema]] issued by [[Pope Damasus I]] at the Council of Rome of 381: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>We pronounce [[anathema]] against them who say that the [[Logos|Word of God]] is in the human flesh in ''lieu'' and place of the human rational and intellective soul."<ref>”Intellective soul," here is synonymous with "mind" or "spirit" ''(pneuma)'' in other discussion of the topic, while the "lower" soul is synonymous with "psyche" or the emotional functions.</ref> For, the Word of God is the Son Himself. Neither did He come in the flesh to replace, but rather to assume and preserve from sin and save the rational and intellective soul of man.</blockquote> | ||

| − | + | The First Ecumenical [[Council of Constantinople]], in the same year, condemned Apollinarism and other heresies in its first act. | |

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | The Faith of the 318 Fathers assembled at Nice in Bithynia shall not be set aside, but shall remain firm. And every heresy shall be anathematized, particularly that of the Eunomians or Eudoxians, and that of the Semi-Arians or Pneumatomachi, and that of the Sabellians, and that of the Marcellians, and that of the Photinians, and that of the Apollinarians.</blockquote> | ||

| − | + | ==Legacy== | |

| − | + | Although it appears somewhat arcane today, the Apollinarian controversy had a major impact on the history of Christian dogma. It transferred the discussion from the [[Trinity]] into the christological field, anticipating both [[Monophysitism]], and [[Nestorianism]], as well as [[Monothelytism]]. It thus opened the long line of christological debates which resulted in the mature "Chalcedonian orthodoxy." | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| + | <references/> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * | + | * This article incorporates content from the 1917 Catholic Encyclopedia, a publication in the [[public domain]]. |

| − | *[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01615b.htm Apollinarism] | + | *[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01615b.htm Apollinarism] Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved September 24, 2007. |

| + | *Brown, Harold O. J. ''Heresies: The Image of Christ in the Mirror of Heresy and Orthodoxy from the Apostles to the Present''. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1984. ISBN 9780385153386 | ||

| + | *Christie-Murray, David. ''A History of Heresy''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989. ISBN 9780192852106 | ||

| + | *Ehrman, Bart D. ''The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture: The Effect of Early Christological Controversies on the Text of the New Testament''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993. ISBN 9780195080780 | ||

| + | *Ferguson, Everett.'' Orthodoxy, Heresy, and Schism in Early Christianity''. Studies in early Christianity, v. 4. New York: Garland, 1993. ISBN 9780815310648 | ||

| + | *Norris, Richard A. ''The Christological Controversy''. Sources of early Christian thought. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1980. ISBN 9780800614119 | ||

| + | *Schwarz, Hans. ''Christology''. Grand Rapids, Mich: W.B. Eerdmans Pub, 1998. ISBN 9780802844637 | ||

[[Category:Philosophy and religion]] | [[Category:Philosophy and religion]] | ||

Latest revision as of 07:33, 4 June 2019

Apollinarism or Apollinarianism was a view proposed by Apollinaris of Laodicea (d. 390 C.E.) that Jesus had a human body and lower soul (the seat of the emotions) but a divine mind. It arose after the doctrine of the Trinity had been systematically formulated in 325 at the Council of Nicea, but debate continued about exactly what it meant. Apollinarism was declared to be a heresy in 381 by the First Council of Constantinople.

Apollianris had developed a solid reputation as a Christian theologian who supported Nicene orthodoxy and courageously defended the Christian faith during the time of Julian the Apostate. His christological formula attempted to solve a logical problem which many Christians had in understanding the Nicene formula; namely, "how could Jesus be 'true God' without losing his humanity?" Apollinaris sought to deal with this problem by saying that Jesus retained a human body and feelings, while his mind was the mind of the Divine Logos.

His ideas were widely popular but ran into stiff criticism from other church leaders, who accused Apollinaris of dividing Christ into artificial parts—making him less than fully divine and more than truly human at the same time—and thus falling into heresy.

Apollinaris refused to recant his views and persisted in teaching them until his death. After this, his movement persisted for some time, but eventually faded. While some of his followers returned to orthodoxy, others would find a home in the later christological movements which addressed the problem he tried to solve: Monophysitism, Monothelitism, and Nestorianism. The Council of Chalcedon ultimately resolved the issue in 451, although Christians today still grapple with the seeming logical inconsistencies of the "mystery" of the Trinity and the Incarnation.

The career of Appolinaris

Apollinaris (Apolinarios) was a bishop of the ancient and prestigious church at Laodicea. He flourished in the latter half of the fourth century and was at first highly esteemed by men such as Athanasius of Alexandria, Basil the Great, and Saint Jerome, due to his classical and biblical learning, his defense of Christianity against paganism during the reign of Julian the Apostate, and his loyalty to the Nicene faith. He assisted his father, Apollinaris the Elder, in popularizing Christian ideas through Greek literary genres. Together they translated the Pentateuch into Greek hexameters, converted the first two books of Kings into an epic poem of 24 cantos, and expressed biblical stories through comedic and tragic dramas. Jerome credits him with many volumes on the scriptures, including two apologies on behalf of Christianity and a refutation of the Arian teacher Eunomius.

The precise time at which Apollinaris began to promulgate the theory which bears his name is uncertain. However, there are apparently two periods in the Apollinarist controversy. Up to 376, although the teaching itself was condemned, Apollinaris' name was never mentioned by his opponents, including Athanasius and Pope Damasus. Nor was he directly criticized in church councils such as that of Alexandria (362), and Rome (376). However, from 376 onward, open and personal theological warfare broke out between him and his critics.

Two late Roman councils, in 377 and 381, plainly denounced and condemned the views of Apollinaris as heretical. More importantly, his views were solemnly anathematized at the ecumenical First Council of Constantinople in 381. Indeed, the first act of this synod entered Apollinarism on the list of heresies. Still convinced that he was not in error, he died about 392.

The movement of Apollinarism

Apollinarism had a considerable following in Constantinople, Syria, and Phoenicia among Christians who grappled with the issues underlying the Council of Nicea. However, after his death, the movement eventually dissipated. Some of his disciples, such as Vitalis, Valentinus, Polemon, and Timothy, tried to perpetuate the teachings of their master and may be responsible for several of pseudonymous writings to that end. A contemporary but anonymous book: Adversus fraudes Apollinaristarum, claims that the Apollinarians, in order to win credence for their teaching, circulated a number of tracts under the names of such famous churchmen as Gregory Thaumaturgus (He kata meros pistis, Exposition of Faith), Athanasius (Peri sarkoseos, On the Incarnation), Pope Julius (Peri tes en Christo enotetos, On Unity in Christ), etc. Some of these works still appear under their supposed authors' names in collections of their works.

The sect, as such, soon became extinct. By 416, many had returned to the orthodox church, while others drifted into Monophysitism and other similar theories.

Doctrine

Apollinaris based his theory on two principles, one objective, and one psychological or subjective.

Objectively, it appeared to him that the union of "true God" with "true man"—the Nicene formula—contained a logical inconsistency, combining two things which could not logically be combined. Two perfect beings with all their attributes, he argued, cannot be completely one, especially when one is infinite and purely spiritual while the other is finite and partly physical. They are at most a compound. To make them absolutely one is not unlike the description of demigods in Greek mythology. However, Apollinaris was careful to affirm that he accepted the Nicene faith, which forbade describing God the Son as anything less than the "same substance" with the Father. Indeed, he was a harsh critic of the Arian theology which the Council of Nicea condemned for failing to affirm this.

Apollinaris attempted to solve the problem by affirming the complete unity of substance between the mind of Jesus and the mind of God. It was in this sense, he said, that Jesus and God were of the "same substance." However, he also affirmed that Jesus' body and feelings were basically human and not completely divine. Thus, Jesus remained both truly human and truly divine, but his human functions were separated from one another.

Apollinaris' conscience would not allow him to affirm Christ's impeccability—his absolute sinlessness—except by affirming that the mind of Jesus' was completely identified with the Divine Logos. Apollinaris appealed to the well-known Platonic division of human nature: body (sarx, soma), lower soul (psyche, halogos), spirit or mind (nous, pneuma, rational soul). Christ, he said, assumed a human body and a human lower soul, but his mind (or rational soul) was the mind of God. In other words, the Logos—the rational soul of God the Son—takes the place of the human mind in Jesus. In this way, God became the rational and spiritual center, the seat of self-consciousness and self-determination, in Jesus Christ.

Though this formula, the Apollinaris sought to save Nicene Christianity from the logical paradox that so many have seen in it. At the same time he hoped to preserve the unity of Christ himself, seeing him not as two things (completely God and completely man at the same time) but one thing (a man with the mind of God). For scriptural confirmation, he quoted from the Gospel John 1:14 ("and the Word was made flesh"), Philemon 2:7 ("Being made in the likeness of men and in habit found as a man"), and I Cor.15:47 (the second man, from heaven, heavenly").

Condemnations

In answering the challenge of Apollinaris, the orthodox Church Fathers of his day had not yet evolved the christological formulas promulgated by the Councils of Ephesus and Chalcedon, which expressed that Christ's human and divine natures were equally present in his person, "without confusion or division." Theodoret of Cyrrhus charged Apollinaris with confusing the persons of the Godhead, and with giving in to the earlier heretical ways of Sabellius. Basil accused him of abandoning the literal sense of the scripture, and taking up wholly with the allegorical sense.

Generally, his critics posited the following arguments:

- Scripture holds that the Logos assumed all that is human in Jesus. The only exception to this is that there was no sin in Christ, as in other humans.

- Christ without a human rational soul, having the mind only of God, is not truly a man. Such a being can neither be called God-man nor stand as the model of Christian life.

- If Christ does not possess a human mind, then this mind is unaffected by his atonement. Thus, the noblest portion of man, his mind (rational soul), is excluded from redemption.

Apollinaris' orthodox critics also pointed out the "correct" meaning of the scriptural passages. Some of them even insisted upon the limitations of Jesus' knowledge as proof positive that his mind was truly human. When Apollinaris sought to draw them into debates about the mystery of the unity of Christ (as both God and man) they often acknowledged their ignorance and derided Apollinaris' insistence on mathematical logic and his implicit reliance upon merely human reasoning. God's ways, they pointed out, are higher than ours, after all.

Eventually, the condemnations reached beyond local bishops and councils to the pope and an ecumenical council. The following condemnation of Apollinarism is found in the seventh anathema issued by Pope Damasus I at the Council of Rome of 381:

We pronounce anathema against them who say that the Word of God is in the human flesh in lieu and place of the human rational and intellective soul."[1] For, the Word of God is the Son Himself. Neither did He come in the flesh to replace, but rather to assume and preserve from sin and save the rational and intellective soul of man.

The First Ecumenical Council of Constantinople, in the same year, condemned Apollinarism and other heresies in its first act.

The Faith of the 318 Fathers assembled at Nice in Bithynia shall not be set aside, but shall remain firm. And every heresy shall be anathematized, particularly that of the Eunomians or Eudoxians, and that of the Semi-Arians or Pneumatomachi, and that of the Sabellians, and that of the Marcellians, and that of the Photinians, and that of the Apollinarians.

Legacy

Although it appears somewhat arcane today, the Apollinarian controversy had a major impact on the history of Christian dogma. It transferred the discussion from the Trinity into the christological field, anticipating both Monophysitism, and Nestorianism, as well as Monothelytism. It thus opened the long line of christological debates which resulted in the mature "Chalcedonian orthodoxy."

Notes

- ↑ ”Intellective soul," here is synonymous with "mind" or "spirit" (pneuma) in other discussion of the topic, while the "lower" soul is synonymous with "psyche" or the emotional functions.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- This article incorporates content from the 1917 Catholic Encyclopedia, a publication in the public domain.

- Apollinarism Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved September 24, 2007.

- Brown, Harold O. J. Heresies: The Image of Christ in the Mirror of Heresy and Orthodoxy from the Apostles to the Present. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1984. ISBN 9780385153386

- Christie-Murray, David. A History of Heresy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989. ISBN 9780192852106

- Ehrman, Bart D. The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture: The Effect of Early Christological Controversies on the Text of the New Testament. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993. ISBN 9780195080780

- Ferguson, Everett. Orthodoxy, Heresy, and Schism in Early Christianity. Studies in early Christianity, v. 4. New York: Garland, 1993. ISBN 9780815310648

- Norris, Richard A. The Christological Controversy. Sources of early Christian thought. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1980. ISBN 9780800614119

- Schwarz, Hans. Christology. Grand Rapids, Mich: W.B. Eerdmans Pub, 1998. ISBN 9780802844637

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.