Difference between revisions of "Anglo-Saxon Poetry" - New World Encyclopedia

Nathan Cohen (talk | contribs) (Imported) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (15 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{Copyedited}} | |

| − | |||

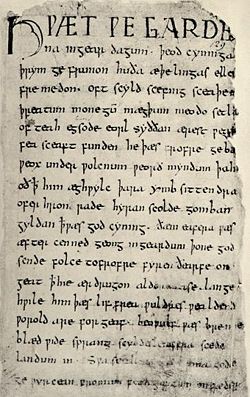

| − | + | [[Image:Beowulf.firstpage.jpeg|right|250px|thumb|First page of Beowulf, contained in the damaged Nowell Codex.]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | '''Anglo-Saxon Poetry''' (or '''Old English Poetry''') encompasses verse written during the 600-year Anglo-Saxon period of British history, from the mid-fifth century to the Norman Conquest of 1066. Almost all of the literature of this period was orally transmitted, and almost all poems were intended for oral performance. As a result of this, Anglo-Saxon poetry tends to be highly rhythmical, much like other forms of verse that emerged from oral traditions. However, Anglo-Saxon poetry does not create rhythm through the techniques of meter and rhyme, derived from Latin poetry, that are utilized by most other Western European languages. Instead, Anglo-Saxon poetry creates rhythm through a unique system of alliteration. Syllables are not counted as they are in traditional European meters, but instead the length of the line is determined by a pattern of stressed syllables that begin with the same consonant cluster. The result of this style of poetry is a harsher, more guttural sound and a rhythm that sounds more like a chant than a traditional song. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Although most Anglo-Saxon poetry was never written down and as such is lost to us, it was clearly a thriving literary language, and there are extant works in a wide variety of genres including epic poetry, Bible translations, historical chronicles, riddles, and short lyrics. Some of the most important works from this period include the epic ''[[Beowulf]]'', [[Caedmon]]'s hymn, [[Bede]]'s ''Death Song'', and the wisdom poetry found in the Exeter Book such as ''The Seafarer'', and ''The Wanderer''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Linguistic and Textual Overview== | ||

| + | A large number of manuscripts remain from the 600 year Anglo-Saxon period, although most were written during the last 300 years (ninth–eleventh century), in both [[Latin]] and the vernacular. Old English is among the oldest vernacular languages to be written down. Old English began, in written form, as a practical necessity in the aftermath of the Danish invasions—church officials were concerned that because of the drop in Latin [[literacy]] no one could read their work. Likewise [[Alfred the Great|King Alfred the Great]] (849–899), noted that while very few could read Latin, many could still read Old English. He thus proposed that students be educated in Old English, and those who excelled would go on to learn Latin. In this way many of the texts that have survived are typical teaching and student-oriented texts. | ||

| − | Not all of | + | In total there are about 400 surviving manuscripts containing Old English text, 189 of them considered major. Not all of these texts can be fairly called literature, but those that can present a sizable body of work, listed here in descending order of quantity: sermons and saints' lives (the most numerous), biblical translations; translated Latin works of the early Church Fathers; Anglo-Saxon chronicles and narrative history works; laws, wills and other legal works; practical works on grammar, medicine, geography; and lastly, poetry. |

| − | Nearly all Anglo-Saxon authors are anonymous, with | + | Nearly all Anglo-Saxon authors are anonymous, with a few exceptions. |

| − | + | ==Works== | |

| − | |||

| − | == | ||

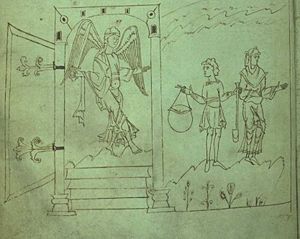

[[Image:CaedmonManuscriptPage46Illust.jpg|thumb|300px|right|In this illustration from page 46 of the Caedmon (or Junius) manuscript, an angel is shown guarding the gates of paradise.]] | [[Image:CaedmonManuscriptPage46Illust.jpg|thumb|300px|right|In this illustration from page 46 of the Caedmon (or Junius) manuscript, an angel is shown guarding the gates of paradise.]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | Old English poetry | + | '''Old English poetry''' is of two types, the pre-Christian and the Christian. It has survived for the most part in four manuscripts. The first manuscript is called the ''Junius manuscript'' (also known as the ''Caedmon manuscript''), which is an illustrated poetic anthology. The second manuscript is called the ''Exeter Book'', also an anthology, located in the Exeter Cathedral since it was donated there in the eleventh century. The third manuscript is called the ''Vercelli Book'', a mix of poetry and prose; how it came to be in Vercelli, Italy, no one knows, and is a matter of debate. The fourth manuscript is called the ''Nowell Codex'', also a mixture of poetry and prose. |

| − | + | Old English poetry had no known rules or system left to us by the Anglo-Saxons, everything we know about it is based on modern analysis. The first widely accepted theory was by Eduard Sievers (1885) in which he distinguished five distinct alliterative patterns. The theory of John C. Pope (1942) inferred that the alliterative patterns of Anglo-Saxon poetry correspond to melodies, and his method adds musical notation to Anglo-Saxon texts and has gained some acceptance. Nonetheless, every few years a new theory of Anglo-Saxon versification arises and the topic continues to be hotly debated. | |

| − | Old English poetry | + | The most popular and well-known understanding of Old English poetry continues to be Sievers' alliterative verse. The system is based upon accent, alliteration, the quantity of vowels, and patterns of syllabic accentuation. It consists of five permutations on a base verse scheme; any one of the five types can be used in any verse. The system was inherited from and exists in one form or another in all of the older Germanic languages. Two poetic figures commonly found in Old English poetry are the ''kenning'', an often formulaic phrase that describes one thing in terms of another (e.g. in ''Beowulf'', the sea is called the "whale road") and ''litotes'', a dramatic understatement employed by the author for ironic effect. |

| − | + | Old English poetry was an oral craft, and our understanding of it in written form is incomplete; for example, we know that the poet (referred to as the ''Scop'') could be accompanied by a [[harp]], and there may be other aural traditions of which we are not aware. | |

===The poets=== | ===The poets=== | ||

| − | Most Old English poets are anonymous; twelve are known by name from Medieval sources, but only four of those are known by their vernacular works to us today with any certainty: [[Caedmon]], [[Bede]], [[Alfred]], and [[Cynewulf]]. Of these, only | + | Most Old English poets are anonymous; twelve are known by name from Medieval sources, but only four of those are known by their vernacular works to us today with any certainty: [[Caedmon]], [[Bede]], King [[Alfred]], and [[Cynewulf]]. Of these, only Caedmon, Bede, and Alfred have known biographies. |

| − | Caedmon is the best-known and considered the father of Old English poetry. He lived at the abbey of | + | Caedmon is the best-known and considered the father of Old English poetry. He lived at the abbey of Whitby in Northumbria in the seventh century. Only a single nine line poem remains, called Caedmon's ''Hymn'', which is also the oldest surviving text in English: |

<div class="notice spoilerbox"><table border="0"><tr><td><div class="toccolours spoilercontents"> | <div class="notice spoilerbox"><table border="0"><tr><td><div class="toccolours spoilercontents"> | ||

| Line 49: | Line 41: | ||

::God Almighty afterwards made the middle world | ::God Almighty afterwards made the middle world | ||

::the earth, for men. | ::the earth, for men. | ||

| − | |||

</div></td></tr></table></div> | </div></td></tr></table></div> | ||

| − | Aldhelm, bishop of | + | Aldhelm, bishop of Sherborne (d. 709), is known to us through William of Malmesbury, who recounts that Aldhelm performed secular songs while accompanied by a harp. Much of his Latin prose has survived, but none of his Old English remains. |

| − | Cynewulf has proven to be a difficult figure to identify, but recent research suggests he was from the early part of the 9th century | + | Cynewulf has proven to be a difficult figure to identify, but recent research suggests he was from the early part of the 9th century. A number of poems are attributed to him, including ''The Fates of the Apostles'' and ''Elene'' (both found in the Vercelli Book), and ''Christ II'' and ''Juliana'' (both found in the Exeter Book). |

===Heroic poems=== | ===Heroic poems=== | ||

| − | + | The Old English poetry which has received the most attention deals with the Germanic heroic past. The longest (3,182 lines), and most important, is ''[[Beowulf]]'', which appears in the damaged Nowell Codex. It tells the story of the legendary Geatish hero, Beowulf. The story is set in Scandinavia, in [[Sweden]] and [[Denmark]], and the tale likewise probably is of Scandinavian origin. The story is historical, heroic, and Christianized even though it relates pre-Christian history. It sets the tone for much of the rest of Old English poetry. It has achieved national epic status in British literary history, comparable to The ''Iliad'' of [[Homer]], and is of interest to historians, anthropologists, literary critics, and students the world over. | |

| − | The Old English poetry which has received the most attention deals with the Germanic heroic past. The longest (3,182 lines), and most important, is ''[[Beowulf]]'', which appears in the damaged Nowell Codex. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Beyond ''Beowulf,'' other heroic poems exist. Two heroic poems have survived in fragments: ''The Fight at Finnsburh'', a retelling of one of the battle scenes in ''Beowulf'' (although this relation to ''Beowulf'' is much debated), and ''Waldere'', a version of the events of the life of Walter of Aquitaine. Two other poems mention heroic figures: ''Widsith'' is believed to be very old, dating back to events in the fourth century concerning Eormanric and the Goths, and contains a catalogue of names and places associated with valiant deeds. ''Deor'' is a lyric, in the style of [[Boethius]], applying examples of famous heroes, including Weland and Eormanric, to the narrator's own case. | |

| − | The 325 line poem '' | + | The 325 line poem ''Battle of Maldon'' celebrates Earl Byrhtnoth and his men who fell in battle against the Vikings in 991. It is considered one of the finest Old English heroic poems, but both the beginning and end are missing and the only manuscript was destroyed in a fire in 1731. A well known speech is near the end of the poem: |

<div class="notice spoilerbox"><table border="0"><tr><td><div class="toccolours spoilercontents"> | <div class="notice spoilerbox"><table border="0"><tr><td><div class="toccolours spoilercontents"> | ||

| Line 71: | Line 59: | ||

::Thought shall be the harder, the heart the keener, courage the greater, as our strength lessens. | ::Thought shall be the harder, the heart the keener, courage the greater, as our strength lessens. | ||

::Here lies our leader all cut down, the valiant man in the dust; | ::Here lies our leader all cut down, the valiant man in the dust; | ||

| − | ::always may he mourn who now | + | ::always may he mourn who now thinks to turn away from this warplay. |

::I am old, I will not go away, but I plan to lie down by the side of my lord, by the man so dearly loved. | ::I am old, I will not go away, but I plan to lie down by the side of my lord, by the man so dearly loved. | ||

| − | ::: | + | :::—''(Battle of Maldon)'' |

</div></td></tr></table></div> | </div></td></tr></table></div> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Wisdom poetry=== | ===Wisdom poetry=== | ||

| − | Related to the heroic tales are a number of short poems from the | + | Related to the heroic tales are a number of short poems from the Exeter Book which have come to be described as "Wisdom poetry." They are lyrical and [[Boethius|Boethian]] in their description of the up and down fortunes of life. Gloomy in mood is ''The Ruin'', which tells of the decay of a once glorious city of Roman Britain (Britain fell into decline after the Romans departed in the early fifth century), and ''The Wanderer'', in which an older man talks about an attack that happened in his youth, in which his close friends and kin were all killed. The memories of the slaughter have remained with him all his life. He questions the wisdom of the impetuous decision to engage a possibly superior fighting force; he believes the wise man engages in warfare to ''preserve'' civil society, and must not rush into battle but seek out allies when the odds may be against him. This poet finds little glory in bravery for bravery's sake. Another similar poem from the Exeter Book is ''The Seafarer'', the story of a somber exile on the sea, from which the only hope of redemption is the joy of heaven. King Alfred the Great wrote a wisdom poem over the course of his reign based loosely on the neo-platonic philosophy of Boethius called the ''Lays of Boethius''. |

===Classical and Latin poetry=== | ===Classical and Latin poetry=== | ||

| − | Several Old English poems are adaptations of | + | Several Old English poems are adaptations of late classical philosophical texts. The longest is a tenth–century translation of Boethius' ''Consolation of Philosophy'' contained in the Cotton manuscript. Another is ''The Phoenix'' in the Exeter Book, an allegorization of the works of Lactantius. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Christian poetry=== | ===Christian poetry=== | ||

====Saints' Lives==== | ====Saints' Lives==== | ||

| − | The Vercelli Book and Exeter Book contain four long narrative poems of saints' lives, or [[hagiography]]. | + | The Vercelli Book and Exeter Book contain four long narrative poems of saints' lives, or [[hagiography]]. The major works of hagiography, the ''Andreas'', ''Elene'', ''Guthlac'', and ''Juliana'' are to be found in the Vercelli and Exeter manuscripts. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ''Andreas'' is 1,722 lines long and is the closest of the surviving Old English poems to ''Beowulf'' in style and tone. It is the story of Saint Andrew and his journey to rescue Saint Matthew from the Mermedonians. ''Elene'' is the story of Saint Helena (mother of Constantine) and her discovery of the True Cross. The cult of the True Cross was popular in Anglo-Saxon England and this poem was instrumental in that promulgation of that belief. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

====Christian poems==== | ====Christian poems==== | ||

| − | In addition to Biblical paraphrases are a number of original religious poems, mostly lyrical | + | In addition to Biblical paraphrases there are a number of original religious poems, mostly lyrical. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Considered one of the most beautiful of all Old English poems is '' | + | Considered one of the most beautiful of all Old English poems is ''Dream of the Rood'', contained in the Vercelli Book. It is a dream-vision, a common genre of Anglo-Saxon poetry in which the narrator of the poem experiences a vision in a dream only to awake from it renewed at the poem's end. In the ''Dream of the Rood'', the dreamer dreams of Christ on the cross, and during the vision the cross itself comes alive, speaking thus: |

<div class="notice spoilerbox"><table border="0"><tr><td><div class="toccolours spoilercontents"> | <div class="notice spoilerbox"><table border="0"><tr><td><div class="toccolours spoilercontents"> | ||

::"I endured much hardship up on that hill. I saw the God of hosts stretched out cruelly. Darkness had covered with clouds the body of the Lord, the bright radiance. A shadow went forth, dark under the heavens. All creation wept, mourned the death of the king. Christ was on the cross." | ::"I endured much hardship up on that hill. I saw the God of hosts stretched out cruelly. Darkness had covered with clouds the body of the Lord, the bright radiance. A shadow went forth, dark under the heavens. All creation wept, mourned the death of the king. Christ was on the cross." | ||

| − | ::: | + | :::—''(Dream of the Rood)'' |

</div></td></tr></table></div> | </div></td></tr></table></div> | ||

| Line 121: | Line 92: | ||

The dreamer resolves to trust in the cross, and the dream ends with a vision of heaven. | The dreamer resolves to trust in the cross, and the dream ends with a vision of heaven. | ||

| − | There are a number of religious debate poems. The longest is '' | + | There are also a number of religious debate poems extant in Old English. The longest is ''Christ and Satan'' in the Junius manuscript, which deals with the conflict between Christ and Satan during the 40 days in the desert. Another debate poem is ''Solomon and Saturn'', surviving in a number of textual fragments, Saturn, the Greek god, is portrayed as a magician debating with the wise king Solomon. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Specific features of Anglo-Saxon poetry=== | ===Specific features of Anglo-Saxon poetry=== | ||

| − | ====Simile and Metaphor ==== | + | ====Simile and Metaphor==== |

| + | Anglo-Saxon poetry is marked by the comparative rarity of similes. This is a particular feature of Anglo-Saxon verse style. As a consequence of both its structure and the rapidity with which its images are deployed it is unable to effectively support the expanded simile. As an example of this, the epic ''Beowulf'' contains at best five similes, and these are of the short variety. This can be contrasted sharply with the strong and extensive dependence that Anglo-Saxon poetry has upon metaphor, particularly that afforded by the use of kennings. | ||

| − | + | ====Rapidity==== | |

| + | It is also a feature of the fast-paced dramatic style of Anglo-Saxon poetry that it is not prone, as was, for example, Celtic literature of the period, to overly elaborate decoration. Whereas the typical Celtic poet of the time might use three or four similes to make a point, an Anglo-Saxon poet might typically make reference to a kenning, before quickly moving to the next image. | ||

| − | ==== | + | ==Historiography== |

| + | Old English literature did not disappear in 1066 with the Norman Conquest. Many sermons and works continued to be read and used in part or as a whole through the fourteenth century, and were further catalogued and organized. During the [[Reformation]], when monastic libraries were dispersed, the manuscripts were collected by antiquarians and scholars. These included Laurence Nowell, Matthew Parker, Robert Bruce Cotton, and Humfrey Wanley. In the 17th century a tradition of Old English literature dictionaries and references was begun. The first was William Somner's ''Dictionarium Saxonico-Latino-Anglicum'' (1659). | ||

| − | + | Because Old English was one of the first vernacular languages to be written down, nineteenth century scholars searching for the roots of European "national culture" took special interest in studying Anglo-Saxon literature, and Old English became a regular part of university curriculum. Since [[World War II]] there has been increasing interest in the manuscripts themselves—Neil Ker, a paleographer, published the groundbreaking ''Catalogue of Manuscripts Containing Anglo-Saxon'' in 1957, and by 1980 nearly all Anglo-Saxon manuscript texts were in print. [[J.R.R. Tolkien]] is credited with creating a movement to look at Old English as a subject of [[literary theory]] in his seminal lecture ''Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics'' (1936). | |

| − | + | Old English literature has had an influence on modern literature. Some of the best-known translations include William Morris' translation of ''Beowulf'' and [[Ezra Pound]]'s translation of ''The Seafarer''. The influence of Old English poetry was particular important for the [[Modernism|Modernist]] poets [[T. S. Eliot]], Ezra Pound and [[W. H. Auden]], who all were influenced by the rapidity and graceful simplicity of images in Old English verse. Much of the subject matter of the heroic poetry has been revived in the fantasy literature of Tolkien and many other contemporary novelists. | |

| − | + | ==References== | |

| + | *Bosworth, Joseph. 1889. ''An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary''. | ||

| + | *Cameron, Angus. 1982. "Anglo-Saxon Literature" in ''Dictionary of the Middle Ages''. Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0684167603 | ||

| + | *Campbell, Alistair. 1972. ''Enlarged Addenda and Corrigenda''. Oxford University Press. | ||

| − | == | + | ==External links== |

| + | All links retrieved July 27, 2023. | ||

| − | + | *[http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/ascp/ The Complete Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Poetry] | |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | [[Category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] |

| − | + | [[category:Literature]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{credit|76667524}} | {{credit|76667524}} | ||

Latest revision as of 06:00, 28 July 2023

Anglo-Saxon Poetry (or Old English Poetry) encompasses verse written during the 600-year Anglo-Saxon period of British history, from the mid-fifth century to the Norman Conquest of 1066. Almost all of the literature of this period was orally transmitted, and almost all poems were intended for oral performance. As a result of this, Anglo-Saxon poetry tends to be highly rhythmical, much like other forms of verse that emerged from oral traditions. However, Anglo-Saxon poetry does not create rhythm through the techniques of meter and rhyme, derived from Latin poetry, that are utilized by most other Western European languages. Instead, Anglo-Saxon poetry creates rhythm through a unique system of alliteration. Syllables are not counted as they are in traditional European meters, but instead the length of the line is determined by a pattern of stressed syllables that begin with the same consonant cluster. The result of this style of poetry is a harsher, more guttural sound and a rhythm that sounds more like a chant than a traditional song.

Although most Anglo-Saxon poetry was never written down and as such is lost to us, it was clearly a thriving literary language, and there are extant works in a wide variety of genres including epic poetry, Bible translations, historical chronicles, riddles, and short lyrics. Some of the most important works from this period include the epic Beowulf, Caedmon's hymn, Bede's Death Song, and the wisdom poetry found in the Exeter Book such as The Seafarer, and The Wanderer.

Linguistic and Textual Overview

A large number of manuscripts remain from the 600 year Anglo-Saxon period, although most were written during the last 300 years (ninth–eleventh century), in both Latin and the vernacular. Old English is among the oldest vernacular languages to be written down. Old English began, in written form, as a practical necessity in the aftermath of the Danish invasions—church officials were concerned that because of the drop in Latin literacy no one could read their work. Likewise King Alfred the Great (849–899), noted that while very few could read Latin, many could still read Old English. He thus proposed that students be educated in Old English, and those who excelled would go on to learn Latin. In this way many of the texts that have survived are typical teaching and student-oriented texts.

In total there are about 400 surviving manuscripts containing Old English text, 189 of them considered major. Not all of these texts can be fairly called literature, but those that can present a sizable body of work, listed here in descending order of quantity: sermons and saints' lives (the most numerous), biblical translations; translated Latin works of the early Church Fathers; Anglo-Saxon chronicles and narrative history works; laws, wills and other legal works; practical works on grammar, medicine, geography; and lastly, poetry.

Nearly all Anglo-Saxon authors are anonymous, with a few exceptions.

Works

Old English poetry is of two types, the pre-Christian and the Christian. It has survived for the most part in four manuscripts. The first manuscript is called the Junius manuscript (also known as the Caedmon manuscript), which is an illustrated poetic anthology. The second manuscript is called the Exeter Book, also an anthology, located in the Exeter Cathedral since it was donated there in the eleventh century. The third manuscript is called the Vercelli Book, a mix of poetry and prose; how it came to be in Vercelli, Italy, no one knows, and is a matter of debate. The fourth manuscript is called the Nowell Codex, also a mixture of poetry and prose.

Old English poetry had no known rules or system left to us by the Anglo-Saxons, everything we know about it is based on modern analysis. The first widely accepted theory was by Eduard Sievers (1885) in which he distinguished five distinct alliterative patterns. The theory of John C. Pope (1942) inferred that the alliterative patterns of Anglo-Saxon poetry correspond to melodies, and his method adds musical notation to Anglo-Saxon texts and has gained some acceptance. Nonetheless, every few years a new theory of Anglo-Saxon versification arises and the topic continues to be hotly debated.

The most popular and well-known understanding of Old English poetry continues to be Sievers' alliterative verse. The system is based upon accent, alliteration, the quantity of vowels, and patterns of syllabic accentuation. It consists of five permutations on a base verse scheme; any one of the five types can be used in any verse. The system was inherited from and exists in one form or another in all of the older Germanic languages. Two poetic figures commonly found in Old English poetry are the kenning, an often formulaic phrase that describes one thing in terms of another (e.g. in Beowulf, the sea is called the "whale road") and litotes, a dramatic understatement employed by the author for ironic effect.

Old English poetry was an oral craft, and our understanding of it in written form is incomplete; for example, we know that the poet (referred to as the Scop) could be accompanied by a harp, and there may be other aural traditions of which we are not aware.

The poets

Most Old English poets are anonymous; twelve are known by name from Medieval sources, but only four of those are known by their vernacular works to us today with any certainty: Caedmon, Bede, King Alfred, and Cynewulf. Of these, only Caedmon, Bede, and Alfred have known biographies.

Caedmon is the best-known and considered the father of Old English poetry. He lived at the abbey of Whitby in Northumbria in the seventh century. Only a single nine line poem remains, called Caedmon's Hymn, which is also the oldest surviving text in English:

|

Aldhelm, bishop of Sherborne (d. 709), is known to us through William of Malmesbury, who recounts that Aldhelm performed secular songs while accompanied by a harp. Much of his Latin prose has survived, but none of his Old English remains.

Cynewulf has proven to be a difficult figure to identify, but recent research suggests he was from the early part of the 9th century. A number of poems are attributed to him, including The Fates of the Apostles and Elene (both found in the Vercelli Book), and Christ II and Juliana (both found in the Exeter Book).

Heroic poems

The Old English poetry which has received the most attention deals with the Germanic heroic past. The longest (3,182 lines), and most important, is Beowulf, which appears in the damaged Nowell Codex. It tells the story of the legendary Geatish hero, Beowulf. The story is set in Scandinavia, in Sweden and Denmark, and the tale likewise probably is of Scandinavian origin. The story is historical, heroic, and Christianized even though it relates pre-Christian history. It sets the tone for much of the rest of Old English poetry. It has achieved national epic status in British literary history, comparable to The Iliad of Homer, and is of interest to historians, anthropologists, literary critics, and students the world over.

Beyond Beowulf, other heroic poems exist. Two heroic poems have survived in fragments: The Fight at Finnsburh, a retelling of one of the battle scenes in Beowulf (although this relation to Beowulf is much debated), and Waldere, a version of the events of the life of Walter of Aquitaine. Two other poems mention heroic figures: Widsith is believed to be very old, dating back to events in the fourth century concerning Eormanric and the Goths, and contains a catalogue of names and places associated with valiant deeds. Deor is a lyric, in the style of Boethius, applying examples of famous heroes, including Weland and Eormanric, to the narrator's own case.

The 325 line poem Battle of Maldon celebrates Earl Byrhtnoth and his men who fell in battle against the Vikings in 991. It is considered one of the finest Old English heroic poems, but both the beginning and end are missing and the only manuscript was destroyed in a fire in 1731. A well known speech is near the end of the poem:

|

Wisdom poetry

Related to the heroic tales are a number of short poems from the Exeter Book which have come to be described as "Wisdom poetry." They are lyrical and Boethian in their description of the up and down fortunes of life. Gloomy in mood is The Ruin, which tells of the decay of a once glorious city of Roman Britain (Britain fell into decline after the Romans departed in the early fifth century), and The Wanderer, in which an older man talks about an attack that happened in his youth, in which his close friends and kin were all killed. The memories of the slaughter have remained with him all his life. He questions the wisdom of the impetuous decision to engage a possibly superior fighting force; he believes the wise man engages in warfare to preserve civil society, and must not rush into battle but seek out allies when the odds may be against him. This poet finds little glory in bravery for bravery's sake. Another similar poem from the Exeter Book is The Seafarer, the story of a somber exile on the sea, from which the only hope of redemption is the joy of heaven. King Alfred the Great wrote a wisdom poem over the course of his reign based loosely on the neo-platonic philosophy of Boethius called the Lays of Boethius.

Classical and Latin poetry

Several Old English poems are adaptations of late classical philosophical texts. The longest is a tenth–century translation of Boethius' Consolation of Philosophy contained in the Cotton manuscript. Another is The Phoenix in the Exeter Book, an allegorization of the works of Lactantius.

Christian poetry

Saints' Lives

The Vercelli Book and Exeter Book contain four long narrative poems of saints' lives, or hagiography. The major works of hagiography, the Andreas, Elene, Guthlac, and Juliana are to be found in the Vercelli and Exeter manuscripts.

Andreas is 1,722 lines long and is the closest of the surviving Old English poems to Beowulf in style and tone. It is the story of Saint Andrew and his journey to rescue Saint Matthew from the Mermedonians. Elene is the story of Saint Helena (mother of Constantine) and her discovery of the True Cross. The cult of the True Cross was popular in Anglo-Saxon England and this poem was instrumental in that promulgation of that belief.

Christian poems

In addition to Biblical paraphrases there are a number of original religious poems, mostly lyrical.

Considered one of the most beautiful of all Old English poems is Dream of the Rood, contained in the Vercelli Book. It is a dream-vision, a common genre of Anglo-Saxon poetry in which the narrator of the poem experiences a vision in a dream only to awake from it renewed at the poem's end. In the Dream of the Rood, the dreamer dreams of Christ on the cross, and during the vision the cross itself comes alive, speaking thus:

|

The dreamer resolves to trust in the cross, and the dream ends with a vision of heaven.

There are also a number of religious debate poems extant in Old English. The longest is Christ and Satan in the Junius manuscript, which deals with the conflict between Christ and Satan during the 40 days in the desert. Another debate poem is Solomon and Saturn, surviving in a number of textual fragments, Saturn, the Greek god, is portrayed as a magician debating with the wise king Solomon.

Specific features of Anglo-Saxon poetry

Simile and Metaphor

Anglo-Saxon poetry is marked by the comparative rarity of similes. This is a particular feature of Anglo-Saxon verse style. As a consequence of both its structure and the rapidity with which its images are deployed it is unable to effectively support the expanded simile. As an example of this, the epic Beowulf contains at best five similes, and these are of the short variety. This can be contrasted sharply with the strong and extensive dependence that Anglo-Saxon poetry has upon metaphor, particularly that afforded by the use of kennings.

Rapidity

It is also a feature of the fast-paced dramatic style of Anglo-Saxon poetry that it is not prone, as was, for example, Celtic literature of the period, to overly elaborate decoration. Whereas the typical Celtic poet of the time might use three or four similes to make a point, an Anglo-Saxon poet might typically make reference to a kenning, before quickly moving to the next image.

Historiography

Old English literature did not disappear in 1066 with the Norman Conquest. Many sermons and works continued to be read and used in part or as a whole through the fourteenth century, and were further catalogued and organized. During the Reformation, when monastic libraries were dispersed, the manuscripts were collected by antiquarians and scholars. These included Laurence Nowell, Matthew Parker, Robert Bruce Cotton, and Humfrey Wanley. In the 17th century a tradition of Old English literature dictionaries and references was begun. The first was William Somner's Dictionarium Saxonico-Latino-Anglicum (1659).

Because Old English was one of the first vernacular languages to be written down, nineteenth century scholars searching for the roots of European "national culture" took special interest in studying Anglo-Saxon literature, and Old English became a regular part of university curriculum. Since World War II there has been increasing interest in the manuscripts themselves—Neil Ker, a paleographer, published the groundbreaking Catalogue of Manuscripts Containing Anglo-Saxon in 1957, and by 1980 nearly all Anglo-Saxon manuscript texts were in print. J.R.R. Tolkien is credited with creating a movement to look at Old English as a subject of literary theory in his seminal lecture Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics (1936).

Old English literature has had an influence on modern literature. Some of the best-known translations include William Morris' translation of Beowulf and Ezra Pound's translation of The Seafarer. The influence of Old English poetry was particular important for the Modernist poets T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound and W. H. Auden, who all were influenced by the rapidity and graceful simplicity of images in Old English verse. Much of the subject matter of the heroic poetry has been revived in the fantasy literature of Tolkien and many other contemporary novelists.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bosworth, Joseph. 1889. An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary.

- Cameron, Angus. 1982. "Anglo-Saxon Literature" in Dictionary of the Middle Ages. Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0684167603

- Campbell, Alistair. 1972. Enlarged Addenda and Corrigenda. Oxford University Press.

External links

All links retrieved July 27, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.