Encyclopedia, Difference between revisions of "Alfred Lord Tennyson" - New World

(Copyedit) |

m |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{Copyedited}}{{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{Contracted}} | {{Copyedited}}{{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{Contracted}} | ||

| − | + | [[Category:Public]] | |

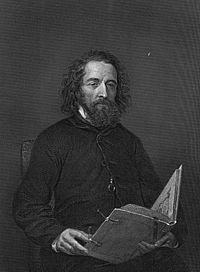

[[Image:Alfred Tennyson 2.jpg|200px|thumb|right|caption|'''Alfred, Lord Tennyson'''<br><small>British Poet Laureate, 1850</small>]] | [[Image:Alfred Tennyson 2.jpg|200px|thumb|right|caption|'''Alfred, Lord Tennyson'''<br><small>British Poet Laureate, 1850</small>]] | ||

Revision as of 16:00, 15 September 2006

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (August 6, 1809 – October 6, 1892) was the Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom after William Wordsworth. As a poet of the Victorian age Tennyson wrote in the shadow of Wordsworth his whole life. Like the rest of the Victorians in the age immediately succeeding the Romanticism of Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lord Byron, John Keats, and William Blake, Tennyson's poetry was written as a reflection on the failure of Romantic attitudes. Some Victorians, such as Algernon Swinburne and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, reacted to the eclipse of Romanticism by become ever wilder and more eccentric than their forebears; but Tennyson, like the majority of Victorians for whom he would serve as a role-model, instead adopted a more stern, moralizing tone. In the wake of the explosive energy of the Romantics, Tennyson, as one of the leaders of what would become a distinctly Victorian voice in poetry, had a style far more attenuated, focused, and sober than that of those of the poets who had preceded him in the first half of the nineteenth century. In both his style and his attitudes, Tennyson strikingly resembled the late Wordsworth, a comparison that is still often invoked either as a point of praise or derision, depending upon one's opinion of the longer, more laborious poetry of Wordsworth's late career.

Like Wordsworth, Tennyson was generally reserved in his political opinions, and his conservatism plays out in his choice of subject matter. Shying away from the fantastical poetry of the previous generation, Tennyson's material is largely grounded in the classics, and his greatest works (Idylls of the King and Ulysses respectively) are concerned with two very old, very much respected legends of King Arthur, and Homer's epic of the Odyssey. Most of Tennyson's poetry is didactic. Like the fables of Aesop, they tend to have a moral or a point. Though perhaps not as exciting as the poets who came before him, Tennyson was, like Wordsworth, an eminently readable poet, and his style provides clear images and consistency of tone. Tennyson provides one of the most refined examples of what might be called traditional poetry, before the revolutions and upheavals that would attend the turn of the twentieth century. As such, he is invaluable to both poets wishing to reestablish a connection with the tradition and to students of all fields wishing to immerse themselves in the literature of an earlier age.

Life

Early life

Alfred Tennyson was born in Lincolnshire, one of 12 children. His father, George Clayton Tennyson, a rector, was the elder of two sons, but was disinherited at an early age by his father, the landowner George Tennyson, in favor of his younger brother Charles, who later took the name Charles Tennyson d'Eyncourt. George Clayton Tennyson raised a large family but was perpetually short of money; he drank heavily and became mentally unstable. Tennyson and two of his elder brothers were writing poetry in their teens, and a collection of poems by all three was published locally when Alfred was only 17. One of those brothers, Charles Tennyson Turner later married Louisa Sellwood, younger sister of Alfred's future wife; the other poet brother was Frederick Tennyson.

Education and first publication

Tennyson attended King Edward VI Grammar School, Louth, and entered Trinity College, Cambridge in 1828, where he joined the secret society called the Cambridge Apostles, a society which would later include a number of noted scientists and philosophers (such as James Clerk Maxwell and Alfred North Whitehead) and which was originally founded as a society for the reading of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. At Cambridge Tennyson met Arthur Henry Hallam, who became his best friend.

He published his first solo collection of poems, Poems Chiefly Lyrical around 1830. “Claribel” and “Mariana,” which later took their place among Tennyson's most celebrated poems, were included in this volume. Although decried by some critics as oversentimental, his verse soon proved popular and brought Tennyson to the attention of well-known writers of the day, including Coleridge himself.

Return to Lincolnshire and second publication

In the spring of 1831, Tennyson's father died, forcing him to leave Cambridge before finishing his degree. He returned to the rectory, where he was permitted to live for another six years, sharing responsibility for his widowed mother and his younger siblings. His friend Hallam came to stay with him during the summer and became engaged to Tennyson's sister, Emilia Tennyson.

In 1833, Tennyson published his second book of poetry, which included one of his better known earlier poems, "The Lady of Shalott," a story of a princess who cannot look at the world except through a reflection in a mirror. As Sir Lancelot rides by the tower where she must stay, she looks at him, and the curse comes to term; she dies after she places herself in a small boat and floats down the river to Camelot, her name written on the boat's stern. The volume met heavy criticism, which so discouraged Tennyson that he did not publish again for ten more years, although he continued to write. A brief quotation of "The Lady of Shalott" serves as a sample of Tennyson's early, sing/song verse:

- On either side the river lie

- Long fields of barley and of rye,

- That clothe the world and meet the sky;

- And through the field the road run by

- To many-tower'd Camelot;

- And up and down the people go,

- Gazing where the lilies blow

- Round an island there below,

- The island of Shalott.

- Willows whiten, aspens quiver,

- Little breezes dusk and shiver

- Through the wave that runs for ever

- By the island in the river

- Flowing down to Camelot.

- Four grey walls, and four grey towers,

- Overlook a space of flowers,

- And the silent isle imbowers

- The Lady of Shalott.

- By the margin, willow veil'd,

- Slide the heavy barges trail'd

- By slow horses; and unhail'd

- The shallop flitteth silken-sail'd

- Skimming down to Camelot:

- But who hath seen her wave her hand?

- Or at the casement seen her stand?

- Or is she known in all the land,

- The Lady of Shalott?

In 1833 Tennyson's close friend Arthur Hallam had a cerebral hemorrhage while on holiday in Vienna and died. It devastated Tennyson, but inspired him to produce a myriad of poetry that has become some of the world's finest verse.

Third publication and recognition

In 1842, while living modestly in London, Tennyson published two volumes of Poems, the first of which included works already published, while the second was made up almost entirely of new poems. They met with immediate success. The Princess, which came out in 1847, was also popular.

The Golden Year

It was in 1850 that Tennyson reached the pinnacle of his career, receiving appointment as poet laureate to succeed William Wordsworth and in the same year producing his masterpiece, In Memoriam A.H.H., dedicated to Arthur Hallam. In the same year, Tennyson married Emily Sellwood, whom he had known since childhood, in the village of Shiplake. They had two sons, Hallam—named after his friend—and Lionel.

The Poet Laureate

He held the position of poet laureate from 1850 until his death, turning out appropriate but mediocre verse, such as a poem of greeting to Alexandra of Denmark when she arrived in Britain to marry the future King Edward VII. In 1855, Tennyson produced one of his best known works, “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” a dramatic tribute to the British cavalrymen involved in an ill-advised charge on October 25, 1854, during the Crimean War against Imperial Russia. Probably more than any other poem, this poem defines Tennyson's career both in its simplicity and its enduring popularity. The poem is relatively short, numbering only 55 lines and six stanzas, and is reproduced in its entirety below.

Half a league half a league

Half a league onward

All in the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred:

'Forward, the Light Brigade

Charge for the guns' he said

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

'Forward, the Light Brigade!'

Was there a man dismay'd?

Not tho' the soldiers knew

Some one had blunder'd:

Theirs not to make reply,

Theirs not to reason why,

Theirs but to do & die,

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon in front of them

Volley'd and thunder'd;

Storm'd at with shot & shell,

Boldly they rode & well,

Into the jaws of Death,

Into the mouth of Hell

Rode the six hundred.

Flash'd all their sabres bare,

Flash'd as they turned in air,

Sabring the gunners there,

Charging an army while

All the world wonder'd:

Plunged in the battery-smoke

Right thro' the line they broke;

Cossack & Russian

Reel'd from the sabre-stroke

Shatter'd & sunder'd.

Then they rode back, but not

Not the six hundred.

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon behind them

Volley'd & thunder'd;

Storm'd at with shot & shell,

While horse & hero fell,

They that had fought so well

Came thro' the jaws of Death

Back from the mouth of Hell,

All that was left of them

Left of six hundred.

When can their glory fade?

O the wild charge they made!

All the world wonder'd.

Honour the charge they made!

Honour the Light Brigade,

Noble six hundred!

Other works written as Laureate include “Ode on the Death of the Duke of Wellington” and “Ode Sung at the Opening of the International Exhibition.”

Queen Victoria was an ardent admirer of Tennyson's work, and in 1884 naming him Baron Tennyson, of Blackdown in the County of Sussex and of Freshwater in the Isle of Wight. He was the first English writer raised to the peerage. A passionate man with some peculiarities of nature, he was never particularly comfortable as a peer, and it is widely held that he took the peerage in order to secure a future for his son Hallam.

Recordings made by Thomas Edison of Lord Tennyson reciting his own poetry have survived, but they are of relatively poor quality.

Tennyson continued writing into his eighties, and died on October 6, 1892, at age 83. He was buried at Westminster Abbey. He was succeeded as 2nd Baron Tennyson by his son, Hallam, who produced an authorized biography of his father in 1897. Hallam was later appointed the second Governor-General of Australia.

Notable works

- “The Kraken”

- Harold - began a revival of interest in King Harold

- “The Charge of the Light Brigade”

- “The Lady of Shalott”

- In Memoriam A.H.H.

- “Ulysses”

- Locksley Hall

- Locksley Hall Sixty Years After

- “Crossing the Bar”

- Tithonus

- Enoch Arden

- The Lotos-Eaters

- Idylls of the King

- Maud

- The Epic

- “Mariana”

External links

- Tennyson's Grave, Westminster Abbey

- Biography & Works (public domain)

- Online copy of 'Locksley Hall'

- Selected Poems of A.Tennyson

- The Twickenham Museum - Alfred Lord Tennyson in Twickenham

- Tennyson in Twickenham

- Works by Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson. Project Gutenberg

- Complete Biography & Works

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Tennyson history

- of the Light Brigade&oldid=54295037 Charge of the Light Brigade of the Light Brigade&action=history history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.