Difference between revisions of "Alexander Gordon Laing" - New World Encyclopedia

(Submitted) |

Laura Brooks (talk | contribs) (image wanted tag, categories) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Claimed}}{{Contracted}}{{Submitted}} | {{Claimed}}{{Contracted}}{{Submitted}} | ||

| − | + | [[Category:Image wanted]] | |

| − | [[Image | ||

| − | |||

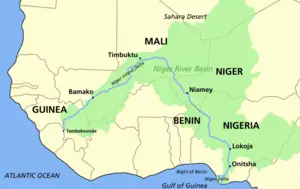

'''Alexander Gordon Laing''' (December 27, 1793–September 26, 1826) was a [[Scotland|Scottish]] [[exploration|explorer]] and army officer who contributed to mapping the source of the Niger and was the first [[Europe]]an in centuries to reach [[Timbuktu]]. He was murdered before he could return to Europe to claim the prize offered by the French Geographical Society. Laing's achievements helped to open up more territory to British commerce and later colonization. His letters provide valuable insight into the attitudes and ambitions of a European in Africa at this time. His career was set in the context of British-French rivalry, which contributed to his ambition to be the first to reach, and to return from, Timbuktu. As territory opened up, interests were established that later translated into colonial domination as the [[Scramble for Africa]] divided the continent up among the European powers. Had Laing lived, he may have achieved greater renown as an explorer. Nonetheless, he left a mark on the [[history]] of European-African enounter which, as one writer put it, changed Africa for ever.<ref>Kryza, 2006</ref>. For Laing and others of his era, Africa was a dark but rich continent where young men could embark on imperial adventures which, potentially, could lead to advancement, discovery, wealth and possibly even power and influence on a scale unobtainable at home. | '''Alexander Gordon Laing''' (December 27, 1793–September 26, 1826) was a [[Scotland|Scottish]] [[exploration|explorer]] and army officer who contributed to mapping the source of the Niger and was the first [[Europe]]an in centuries to reach [[Timbuktu]]. He was murdered before he could return to Europe to claim the prize offered by the French Geographical Society. Laing's achievements helped to open up more territory to British commerce and later colonization. His letters provide valuable insight into the attitudes and ambitions of a European in Africa at this time. His career was set in the context of British-French rivalry, which contributed to his ambition to be the first to reach, and to return from, Timbuktu. As territory opened up, interests were established that later translated into colonial domination as the [[Scramble for Africa]] divided the continent up among the European powers. Had Laing lived, he may have achieved greater renown as an explorer. Nonetheless, he left a mark on the [[history]] of European-African enounter which, as one writer put it, changed Africa for ever.<ref>Kryza, 2006</ref>. For Laing and others of his era, Africa was a dark but rich continent where young men could embark on imperial adventures which, potentially, could lead to advancement, discovery, wealth and possibly even power and influence on a scale unobtainable at home. | ||

| Line 57: | Line 55: | ||

[[Category:Biography]] | [[Category:Biography]] | ||

| − | + | [[Category:Explorers]] | |

{{Credit|161564339}} | {{Credit|161564339}} | ||

Revision as of 00:26, 22 October 2007

Alexander Gordon Laing (December 27, 1793–September 26, 1826) was a Scottish explorer and army officer who contributed to mapping the source of the Niger and was the first European in centuries to reach Timbuktu. He was murdered before he could return to Europe to claim the prize offered by the French Geographical Society. Laing's achievements helped to open up more territory to British commerce and later colonization. His letters provide valuable insight into the attitudes and ambitions of a European in Africa at this time. His career was set in the context of British-French rivalry, which contributed to his ambition to be the first to reach, and to return from, Timbuktu. As territory opened up, interests were established that later translated into colonial domination as the Scramble for Africa divided the continent up among the European powers. Had Laing lived, he may have achieved greater renown as an explorer. Nonetheless, he left a mark on the history of European-African enounter which, as one writer put it, changed Africa for ever.[1]. For Laing and others of his era, Africa was a dark but rich continent where young men could embark on imperial adventures which, potentially, could lead to advancement, discovery, wealth and possibly even power and influence on a scale unobtainable at home.

Biography

Laing was born at Edinburgh. He was educated by his father, William Laing, a private teacher of classics, and at Edinburgh University. After assisting his father running the Academy, and for a short time a school master in Newcastle, he volunteered for military service in 1809, becoming and ensign in the Prince of Wales Volunteers. In 1811 he went to Barbados as clerk to his maternal uncle Colonel (afterwards General) Gabriel Gordon, then deputy quarter-master general, hoping for a transfer to the regular army. He was following in the footsepts of many fellow Scots, for whom the British Empire provided opportunites for social, economic or for political advancement beyond what Scotland's sphere could offer. Through General Sir George Beckwith, governor of Barbados, he obtained a commission in the York Light Infantry. He was then employed in the West Indies where he was soon performing the duties of a quatermaster general. A bout of illness followed, during which he recuperated in Scotland. He was also on half-pay during this eighteen-month period. However, by 1819 he was fully restored to health and looking to rejoin his regiment. Due to reports of competent service in the West Indies, he was promoted to a lieutenant in the Royal African Corps and despatched to Sierra Leone.

Exploring Africa" The Niger Valley

It was in 1822 that his exploits as an explorer began when he was sent by the governor Sir Charles MacCarthy, to the Mandingo country, with the double object of opening up commerce and endeavouring to abolish the slave trade in that region. Later in the same year, promoted to Captain, Laing visited Falaba, the capital of the Solimana country, and located the source of the Rokell. Laing had personally requested this mission, suggesting to the Governor that Falaba was rich in gold and ivory. He also tried to reach the source of the Niger, but was stopped by the local population within about three days march of the source. He did, though, fix the location with approximate accuracy. He later reported that he was the first whiteman seen by the Africans in that region. His memoir tells us of his attitude towards Africans at this point, typical of what became the dominant European view:

- Of the Timmanees he writes in his journal very unfavourably; he found them depraved, indolent, avaricious, and so deeply sunk in the debasement of the slave traffic, that the very mothers among them raised a clamour against him for refusing to buy their children. He further accuses them of dishonesty and gross indecency, and altogether wonders that a country so near Sierra Leone, should have gained so little by its proximity to a British settlement[2].

Promises by the King of Soolima to send back with him a company of traders never materialized. He returned to base empty handed but with data on the topography.

Ashanti War

During 1823 and 1824, he took an active part in the Ashanti War, which was part of the anti-slave campaign and was sent home with the despatches containing the news of the death in action of Sir Charles MacCarthy. The war, as well as Laing's explorations, were part of what later writers called the "pacification" of Africa, at least from the European point of view.

While in England in 1824 he prepared a narrative of his earlier journeys, which was published in 1825 and entitled Travels in the Timannee, Kooranko and Soolima Countries, in Western Africa.

Henry, 3rd Earl Bathurst, then secretary for the colonies, instructed Captain Laing to undertake a journey, via Tripoli and Timbuktu, to further elucidate the hydrography of the Niger basin. Laing left England in February 1825, and at Tripoli on the 14th of July he married Emma Warrington, daughter of the British consul. Kryza describes him at this point as "a tall, trimly built man ... who carried himself with ... self-assurance" [3] who fell "instantly in love" with Emma.[4]. Two days later, leaving his bride behind, he started to cross the Sahara, being accompanied by a sheikh who was subsequently accused of planning his murder. Ghadames was reached, by an indirect route, in October 1825, and in December Laing was in the Tuat territory, where he was well received by the Tuareg.

Timbuktu

On the 10th of January 1826, now a Major, he left Tuat and made for the almost legendary Timbuktu, believed to be a "city of gold" across the desert of Tanezroft. He was actually taking part in a race for the fabled city, launched in 1824 when the French Geographical Society offered a prize of 10,000 frands for the first perosn to reach Timbuktu, and "live to tell the tale". [5]. The British wanted to beat the French. However, as well as commissioning Laing, they also commissioned Hugh Clapperton, expecting that the two men would co-operate. Instead, Copperton planned his own mission. This may account for lack of careful planning by Laing, whose 2,000 mile journey quickly encountered problems. His Letters written in the following May and July tell of his nsufferings from fever and of the plundering of his caravan by Tuareg, In January, 2006 his camp was attacked and Laing himself was seriosuly wounded - in twenty-four places - during the fighting. He refers to these injuries in a letter to his father-in-law dated May 10th, 2006. Another letter dated from Timbuktu on the 21st of September announced his arrival in that city on the preceding 18th of August, and the insecurity of his position owing to the hostility of the Fula chieftain Bello, then ruling the city. He added that he intended leaving Timbuktu in three days time. No further news was received from the traveller. In their dealings with African leaders, the British tended to assume that their presence in Africa would be welcome, even that territory would be ceded or trade concessions made almost as if they had an automatic right to these. On route, says Kryza, the caravan master faced a dilemma, of which Laing was propably unaware:

- On the one hand, as a traveler who was undoubdebtly rich (in Babani's eyes, all Englishmen were rich), Laing occupied a place near the top of the ladder. On the other hand, as an infidel from a country populated by unclean kafirs, Laing was lucky to be tolerated at all, and surely meritted the bottom rung.[6]

Laing, in his dealing with African kings, certainly saw himself as their better, although even as a Major his rank was actually rarher modest.

Death

Local information indicates that he left Timbuktu on the day he had planned and was murdered on the night of the 26th of September 1826. His papers were never recovered, though it is believed that they were secretly brought to Tripoli in 1828. In 1903 the French government placed a tablet bearing the name of the explorer and the date of his visit on the house occupied by him during his thirty-eight days stay in Timbuktu.

Context of his life

Africa was regarded by the European powers as ripe for commerce and colonization. Europe needed raw materials to fuel its Industrial Revolution, and Africa was an obvious source of resources. Encounter with Africans led Europeans to posit their own superiority, and soon the expolitative aim of colonization was accompanied by the conviction that by dominating Africa, they were also civilizing it. Laing's countryman, David Livingstone, who first went to Africa in 1841, set three goals, to end slavery, to convert Africans and to spread civilization. In fact, the developmental gap between Africa and Europe was not that wide. Europe's advantage lay mainly in navigation and warfare. Before Africa could be expolited, it first had to be explored. Quite a few early exploreres were missionaries but government employed explorers, such as Laing, also played key roles. Niger became contested territory between the French and the British. The region known later as Nigeria, however, became an area of British influence and eventually a colony. Laing's early explorations contributed significantly to British ambition in this area. Kryza paints a picture of Laing as a new type of explorer, who, in pursuit of a "new and glorious calling" penetrated the African interior "for the sole purpose of finding out" what was there. This soon captured the European imagination, and filled it literature. [7]. In this view, Laing fits the Orientalist mold of someone who saw Africa as something to be possessed. For the European, Africa was there to be "taken", to be explored, to map, to make the location of one's career.

Legacy

Kyrza says that men such as Laing changed Africa for ever. Kryza (2006) has used Laing's correspondence to rconstruct the story of his race for Timbuktu, which he sets in the broader context of what was effectively the beginning of the Scramble for Africa. Laing's exploration ensured that much of the Niger river region fell within the British sphere of infuence, a rich prize given the usefulnes of the Niger River for purposes of communication and transportation. Within a century, with the exception of Ethiopia, the whole of Africa was under European rule. When the continent was divided up, the presence of existing interests was a major factor in determining how the distribution was made. Kryza writes of a new type of European hero, the lone, brave African explorer who penetrates the heart of the continent with the sole purpose of finding out what is there to be found, and says that tales of their exploits soon "captured the imagination, fed the fantasies and filled the literature of Europe" [8]. Laing does appear to have thrived on adventure, but he was not quite the disinterested explorer. His eagerness to explore where he thought ivory and gold could be found suggests that he was also interested in earning his own fortune. In his comments on Africans, we see the type of effortless superiority that made it easy for Europeans to exploit and dominate people they thought inferior to themselves.

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bovill, E. W. Missions to the Niger. Nendeln, Liechtenstein: Kraus Reprint, 1975.

- Kryza, Frank T. The Race for Timbuktu In Search of Africa's City of Gold. New York: Ecco, 2006 ISBN 9780060560645

- Laing, Alexander Gordon Travels in the Timannee, Kooranko and Soolima Countries, in Western Africa, London: John Murray, 1825; Boston, MA: Adamant Media, 2001 ISBN 978-1402173912

- Fleming, Fergus. Off the Map Tales of Endurance and Exploration. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2005, ISBN 9780871138996

- McCullin, Don. Hearts of Darkness. New York: Knopf, 1981 ISBN 9780394514765

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External Links

- Laing at "Significant Scots" includes some of his correspondence Retrieved October 16, 2007.

- Biography at NNDB Retrieved October 16, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.