Tlingit

| Tlingit |

|---|

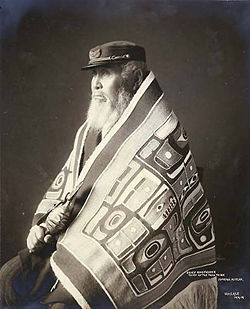

Chief Anotklosh of the Taku Tribe, ca. 1913 |

| Total population |

| 11,000 |

| Regions with significant populations |

| USA (Alaska), Canada (British Columbia, Yukon) |

| Languages |

| English, Tlingit |

| Religions |

| Christianity, other |

The Tlingit (IPA: /'klɪŋkɪt/, also /-gɪt/ or /'tlɪŋkɪt/ which is often considered inaccurate) are an Indigenous people. Their name for themselves is Lingít (/ɬɪŋkɪt/) , meaning "people". The Russian name Koloshi (from an Aleut term for the labret) or the related German name Koulischen may be encountered in older historical literature.

The Tlingit are a matrilineal society who developed a complex hunter-gatherer culture in the temperate rainforest of the southeast Alaska coast and the Alexander Archipelago. The Tlingit language is well known not only for its complex grammar and sound system but also for using certain phonemes which are not heard in almost any other language.

Territory

The maximum territory historically occupied by the Tlingit extended from the Portland Canal along the present border between Alaska and British Columbia north to the coast just southeast of the Copper River delta. The Tlingit occupied almost all of the Alexander Archipelago except the southernmost end of Prince of Wales Island and its surroundings into which the Kaigani Haida moved just before the first encounters with European explorers. Inland the Tlingit occupied areas along the major rivers which pierce the Coast Mountains and Saint Elias Mountains and flow into the Pacific, including the Alsek, Tatshenshini, Chilkat, Taku, and Stikine rivers. With regular travel up these rivers the Tlingit developed extensive trade networks with Athabascan tribes of the interior, and commonly intermarried with them. From this regular travel and trade, a few relatively large populations of Tlingit settled around the Atlin, Teslin, and Tagish lakes, the headwaters of which flow from areas near the headwaters of the Taku River.

Delineating the modern territory of the Tlingit is complicated by the fact that they are spread across the border between the United States and Canada, by the lack of designated reservations, other complex legal and political concerns, and a relatively high level of mobility among the population. In Canada, the modern communities of Atlin, British Columbia (Taku River Tlingit), Teslin, Yukon (Teslin Tlingit Council), and Carcross, Yukon (Carcross/Tagish First Nation) have reserves and are the representative Interior Tlingit populations. The territory occupied by the modern Tlingit people in Alaska is however not restricted to particular reservations, unlike most tribes in the contiguous 48 states. This is the result of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) which established regional corporations throughout Alaska with complex portfolios of land ownership rather than bounded reservations administered by tribal governments. The corporation in the Tlingit region is Sealaska, Inc. which serves the Tlingit as well as the Haida in Alaska. Tlingit people as a whole participate in the commercial economy of Alaska, and as a consequence live in typically American nuclear family households with private ownership of housing and land. Many also possess land allotments from Sealaska or from earlier distributions predating ANCSA. Despite the legal and political complexities, the territory historically occupied by the Tlingit can be reasonably designated as their modern homeland, and Tlingit people today envision the land from around Yakutat south through the Alaskan Panhandle and including the lakes in the Canadian interior as being Lingít Aaní, the Land of the Tlingit.

The extant Tlingit territory can be roughly divided into four major sections, paralleling ecological, linguistic, and cultural divisions. The Southern Tlingit occupy the region south of Frederick Sound, and live in the northernmost reaches of the Western Redcedar forest. North of Frederick Sound to Cape Spencer, and including Glacier Bay and the Lynn Canal, are the Northern Tlingit, who occupy the warmest and richest of the Sitka Spruce and Western Hemlock forest. The Interior Tlingit live along the large interior lakes and the drainage of the Taku River, and subsist in a manner similar to their Athabascan neighbors in the mixed spruce taiga. North of Cape Spencer, along the coast of the Gulf of Alaska to Controller Bay and Kayak Island, are the Gulf Coast Tlingit, who live along a narrow strip of coastline backed by steep mountains and extensive glaciers, and battered by Pacific storms. The trade and cultural interactions between each of these Tlingit groups and their disparate neighbors, the differences in food harvest practices, and the dialectical differences contribute to these identifications which are also supported by similar self-identifications among the Tlingit.

Culture

- Main article: Culture of the Tlingit

The Tlingit culture is multifaceted and complex, a characteristic of Northwest Pacific Coast peoples with access to easily exploited rich resources. In Tlingit culture a heavy emphasis is placed upon family and kinship, and on a rich tradition of oratory. Wealth and economic power are important indicators of status, but so is generosity and proper behavior, all signs of "good breeding" and ties to aristocracy. Art and spirituality are incorporated in nearly all areas of Tlingit culture, with even everyday objects such as spoons and storage boxes decorated and imbued with spiritual power and historical associations.

Food

- Main article: Food of the Tlingit

Food is a central part of Tlingit culture, and the land is an abundant provider. A saying amongst the Tlingit is that "when the tide goes out the table is set". This refers to the richness of intertidal life found on the beaches of Southeast Alaska, most of which can be harvested for food. Another saying is that "in Lingít Aaní you have to be an idiot to starve". Since food is so easy to gather from the beaches, a person who can't feed himself at least enough to stay alive is considered to be a fool, perhaps mentally incompetent or suffering from very bad luck. However, though eating off the beach would provide a fairly healthy and varied diet, eating nothing but "beach food" is considered contemptible among the Tlingit, and a sign of poverty. Indeed, shamans and their families were required to abstain from all food gathered from the beach, and men might avoid eating beach food before battles or strenuous activities in the belief that it would weaken them spiritually and perhaps physically as well. Thus for both spiritual reasons as well as to add some variety to the diet, the Tlingit harvest many other resources for food besides those which are easily found outside their front doors. No other food resource receives as much emphasis as salmon, however seal and game are both close seconds.

Philosophy and religion

- Main article: Philosophy and religion of the Tlingit

Tlingit thought and belief, although never formally codified, was historically a fairly well organized philosophical and religious system whose basic axioms shaped the way all Tlingit people viewed and interacted with the world around them. Between 1886-1895, in the face of their shamans' inability to treat Old World diseases including smallpox, most of the Tlingit people converted to Orthodox Christianity. (Russian Orthodox missionaries had translated their liturgy into the Tlingit language.) After the introduction of Christianity, the Tlingit belief system began to erode.

Today, some young Tlingits look back towards what their ancestors believed, for inspiration, security, and a sense of identity. This causes some friction in Tlingit society, because most modern Tlingit elders are fervent believers in Christianity, and have transferred or equated many Tlingit concepts with Christian ones. Indeed, many elders believe that resurrection of heathen practices of shamanism and spirituality are dangerous, and are better forgotten.

History

- Main article: History of the Tlingit

The history of the Tlingit involves both pre-contact and post-contact historical events and stories. The traditional history involved the creation stories, the Raven Cycle, other tangentially related events during the mythic age when spirits freely transformed from animal to human and back, the migration story of coming to Tlingit lands, the clan histories, and more recent events near the time of first contact with Europeans. At this point the European and American historical records come into play, and although modern Tlingits have access to and review these historical records, they continue to maintain their own historical record by telling stories of ancestors and events which have importance to them against the background of the changing world.

Prominent Tlingits

- Diane E. Benson, politician

- Nora Marks Dauenhauer, writer and scholar

- George Hunt, ethnologist (adopted into Kwakwaka'wakw)

- William Paul, Native rights activist

- Elizabeth Peratrovich, political activist

- Louis Shotridge, ethnologist

Anthropologists and other scholars who have worked among the Tlingit

- Nora Marks Dauenhauer

- Richard Dauenhauer

- George T. Emmons

- Viola Garfield

- Frederica de Laguna

- Kirk Dombrowski

- Sergei Kan

- Edward L. Keithahn

- Aurel Krause

- Steve J. Langdon

- Jeff Leer

- Catherine McClellan

- Madonna Moss

- Kalervo Oberg

- Ronald Olson

- Louis Shotridge

- Ian Stevenson

- John R. Swanton

- Thomas F. Thornton

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ames, Kenneth M. & Maschner, Herbert D.G. (1999). Peoples of the Northwest Coast: Their archaeology and prehistory. London: Thames and Hudson, Ltd. ISBN 0-500-28110-6.

- Bullen, Edward L. (1968). An historical study of the education of the Indians of Teslin, Yukon Territory. (Unpublished master's thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton).

- Emmons, George Thornton (1991). The Tlingit Indians. Volume 70 in Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History. Edited with additions by Frederica De Laguna. New York: American Museum of Natural History. ISBN 0-295-97008-1.

- Dauenhauer, Nora Marks & Dauenhauer, Richard (1987). Haa Shuká, Our Ancestors: Tlingit oral narratives. Volume 1 in Classics of Tlingit Oral Literature. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-96495-2.

- ——— (1990). Haa Tuwunáagu Yís, for Healing our Spirit: Tlingit oratory. Volume 2 in Classics of Tlingit Oral Literature. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-96850-8.

- ——— (1994). Haa Kusteeyí, Our Culture: Tlingit life stories. Volume 3 in Classics of Tlingit Oral Literature. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-97401-X.

- De Laguna, Frederica (1960). The Story of a Tlingit Community. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology: bulletin 172. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ——— (1972). Under Mount Saint Elias: The history and culture of the Yakutat Tlingit. Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology: volume 7 (in three parts). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ——— (1990). Tlingit. In W. Suttles (Ed.), Northwest Coast (pp. 203-228). Handbook of North American Indians (Vol. 7) (W. C. Sturtevant, General Ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Dombrowski, Kirk (2001) Against Culture: Development, Politics and Religion in Indian Alaska. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Eliade, Mircea (1964). Shamanism: Archaic techniques of ecstasy. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01779-4.

- French, Diana E. (1974). Taku recovery project: A preliminary report for the Atlin band. Archaeology Sites Advisory Board permit no. 29-73. (Unpublished).

- Garfield, Viola E. (1947). "Historical aspects of Tlingit clans in Angoon, Alaska". American Anthropologist 49:438–453.

- Garfield, Viola E. & Forrest, Linn A. (1961). The Wolf and the Raven: Totem poles of Southeast Alaska. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-73998-3.

- Goldschmidt, Walter R. and Haas, Theodore H. (1998). Haa Aaní, Our Land. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-97639-X.

- Holm, Bill (1965). Northwest Coast Indian Art: An analysis of form. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-95102-8

- Hope III, Andrew (1982). Raven's Bones. Sitka, Alaska: Sitka Community Association. ISBN 0-911417-00-1.

- ——— (2000). Will the Time Ever Come? : A Tlingit sourcebook. Fairbanks, Alaska: Alaska Native Knowledge Network. ISBN 1-877962-34-1.

- Huteson, Pamela Rae (2002). Legends in Wood, Stories of the Totems. Portland, Oregon: Greatland Classic Sales. ISBN 1-886462-51-8

- Kaiper, Nan (1978). Tlingit: Their art, culture, and legends. Vancouver, British Columbia: Hancock House Publishers, Ltd. ISBN 0-88839-010-6.

- Kamenskii, Fr. Anatolii (1985). Tlingit Indians of Alaska. Translated with additions by Sergei Kan. Volume II in Marvin W. Falk (Ed.), The Rasmuson Library Historical Translations Series. Fairbanks, Alaska: University of Alaska Press. Originally published as Indiane Aliaski, Odessa, 1906. ISBN 0-912006-18-8.

- Kan, Sergei (1989). Symbolic Immortality: The Tlingit potlatch of the nineteenth century. William L. Merrill and Ivan Karp (Eds.), Smithsonian Series in Ethnographic Inquiry. ISBN 1-56098-309-4.

- Krause, Arel (1956). The Tlingit Indians. Translated by Erna Gunther. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press. Originally published as Die Tlinkit-Indianer, Jena, 1885. ISBN 0-295-95075-7.

- McClellan, Catharine (1950). Culture change and native trade in southern Yukon territory. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of California, Berkeley).

- ——— (1953). The inland Tlingit. In M. W. Smith (Ed.), Asia and North America: Transpacific contacts (pp. 47-51). Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology (No. 9). Salt Lake City: Society for American Archaeology. (Reprinted 1974, 1979).

- ——— (1954). The interrelations of social structure with northern Tlingit ceremonialism. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, 10 (1), 75-96.

- ——— (1970). Indian stories about the first whites in northwestern America. In M. Lantis (Ed.), Ethnohistory in southwestern Alaska and the southern Yukon: Method and content (pp. 103-133). Studies in anthropology (No. 7). Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

- ——— (1975). My old people say: An ethnographic survey of southern Yukon territory. [2 books]. Publications in Ethnology (No. 6). Ottawa: National Museum of Man (National Museums of Canada).

- ——— (1981). Inland Tlingit. In J. Helm (Ed.), Subarctic (pp. 469-480). Handbook of Native American Indians (Vol. 6) (W. C. Sturtevant, Gen. Ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- McClellan, Catharine; & Rainier, Dorothy. (1950). Ethnological survey of southern Yukon territory, 1948. (Preliminary report). National Museum of Canada Bulletin, 118, 50-53.

- Moss, Madonna Lee (1989). Archaeology and cultural ecology of the prehistoric Angoon Tlingit. Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Santa Barbara.

- Peratrovich, Robert J. Jr. (1959). Social and economic structure of the Henya Indians. Masters dissertation, University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

- Salisbury, O.M. (1962). The customs and legends of the Thlinget Indians of Alaska. New York: Bonanza Books. ISBN 0-517-13550-7.

- Swanton, John R. (1909). Tlingit myths and texts. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology: bulletin 39. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Teslin Women's Institute (1972). A history of the settlement of Teslin. Teslin, Yukon.

See also

- Battle of Sitka

External links

- Sealaska Heritage Institute

- Sealaska Inc.

- Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska

- Contemporary Tlingit Artist-Nicholas Galanin

- Raven Trickster Larry McNeil Creation Stories Raven Stories

- Tlingit National Anthem, Alaska Natives Online

- Tlingit Tribes, Clans and Clan Houses (includes map)

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections – Alaskan Tlingit and Tsimshian Dr. Jay Miller of the University of Washington examines the Tlingit of the Alaskan panhandle and neighboring Tsimshian of the British Columbia coast.

- Taku River Tlingit First Nation (British Columbia)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.