Encyclopedia, Difference between revisions of "Robert K. Merton" - New World

(copied from Wikipedia) |

|||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

{{epname}} | {{epname}} | ||

| + | |||

'''Robert King Merton''' ([[July 4]], [[1910]] – [[February 23]], [[2003]], born ''Meyer R. Schkolnick'' to immigrant parents) was a distinguished American [[sociologist]] perhaps best known for having coined the phrase "[[self-fulfilling prophecy]]." He also coined many other phrases that have gone into everyday use, such as "[[role model]]" and "[[unintended consequences]]". He spent most of his career teaching at [[Columbia University]], where he attained the rank of University Professor. | '''Robert King Merton''' ([[July 4]], [[1910]] – [[February 23]], [[2003]], born ''Meyer R. Schkolnick'' to immigrant parents) was a distinguished American [[sociologist]] perhaps best known for having coined the phrase "[[self-fulfilling prophecy]]." He also coined many other phrases that have gone into everyday use, such as "[[role model]]" and "[[unintended consequences]]". He spent most of his career teaching at [[Columbia University]], where he attained the rank of University Professor. | ||

| − | + | The dissertation, a quantitative social history of the development of science in seventeenth-century England, reflected this interdisciplinary committee.[Merton, 1985] | |

==Biography== | ==Biography== | ||

| − | Robert K. Merton was born in [[working class]] [[Jew]]ish [[Eastern European]] immigrants family, on July 4, 1910, in [[Philadelphia]]. Educated in the [[South Philadelphia High School]], he became a frequent visitor of the nearby [[Carnegie library|Andrew Carnegie Library]], The Academy of Music, Central Library, Museum of Arts and other cultural and educational centres. He started his sociological career under the guidance of [[George E. Simpson]] in [[Temple College]] (1927-1931), and [[Pitrim A. Sorokin]] in [[Harvard University]] (1931-1936).[Sztompka, 2003] | + | Robert K. Merton was born in [[working class]] [[Jew]]ish [[Eastern European]] immigrants family, on July 4, 1910, in [[Philadelphia]]. Educated in the [[South Philadelphia High School]], he became a frequent visitor of the nearby [[Carnegie library|Andrew Carnegie Library]], The Academy of Music, Central Library, Museum of Arts and other cultural and educational centres. He started his sociological career under the guidance of [[George E. Simpson]] in [[Temple College]] (1927-1931), and [[Pitrim A. Sorokin]] in [[Harvard University]] (1931-1936).[Sztompka, 2003]. |

| + | |||

| + | It is a popular misconception that Robert K. Merton was one of [[Talcott Parsons]]’ students. Parsons was only a junior member of his dissertation committee, the others being [[Pitirim Sorokin]], Carle C. Zimmermanm and the historian of science, [[George Sarton]]. Merton was, on the other hand, heavily influenced by [[Pitirim Sorokin]], who tried to balance large-scale theorizing with a strong interest in empirical research and statistical studies. Sorokin and [[Paul Lazarsfeld]] influenced Merton to occupy himself with [[Middle range theory (sociology)|middle-range theories]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | He taught at Harvard until 1939, when he became professor and chairman of the Department of Sociology at [[Tulane University]]. In 1941 he joined the [[Columbia University]] faculty, becoming [[Giddings Professor of Sociology]] in 1963. He was named to the University's highest academic rank, University Professor, in 1974 and became Special Service Professor upon his retirement in 1979, a title reserved by the Trustees for emeritus faculty who "''render special services to the University''." | ||

| + | |||

| + | In recognition of his lasting contributions to scholarship and the University, Columbia established the Robert K. Merton Professorship in the Social Sciences in 1990. He was associate director of the University's Bureau of Applied Social Research from 1942 to 1971. He was an adjunct faculty member at [[Rockefeller University]] and was also the first [[Foundation Scholar]] at the [[Russell Sage Foundation]].[http://www.columbia.edu/cu/record/archives/vol20/vol20_iss2/record2002.13.html] He withdrew from teaching in 1984.[Sztompka, 2003] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Merton was married twice, including to fellow sociologist [[Harriet Zuckerman]]. He has two sons and two daughters from the first marriage, including [[Robert Carhart Merton]], winner of the 1997 [[Nobel Prize in economics]]. He died in 2003. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Works == | ||

| + | ==''Social structure and anomie''== | ||

| + | ==="Social structure and anomie" in 1938 edition=== | ||

| + | Robert Merton set out to expand upon the concept of [[Durkheim]]’s [[anomie]]. Merton began by stating that there are two elements of social and cultural structure. The first structure is culturally assigned goals and aspirations (Merton 1938, p. 672). These are the things that all individuals should want and expect out of life. Including success, money, material things, etc. The second aspect of the social structure defines the acceptable mode for achieving the goals and aspirations set by society (Merton 1938, p. 673). | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is the appropriate way that people get what they want and expect out of life. Examples include obeying laws and societal norms, seeking an education and hard work. In order for society to maintain a normative function there must be a balance between aspirations and means in which to fulfill such aspirations (Merton 1938, pp. 673-674). | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to Merton, balance would occur as long as the individual felt that he was achieving the culturally desired goal by conforming to the “''institutionally accepted mode of doing so''” (Merton, 1938, p. 674). | ||

| + | |||

| + | In other words, there must be an intrinsic payoff, an internal satisfaction that one is playing by the rules and there must also be an extrinsic payoff, achieving their goals. It is also important that the culturally desired goals be achievable by legitimate means for all social classes. If goals are not equally achievable through an accepted mode, then illegitimate means might be used to achieve the same goal. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==="Social Structure and anomie" in 1949 edition=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Merton changed the definition of cultural aspirations to include those goals held out as legitimate objectives for all or for diversely located members of society. In his explanation of means he reworded the definition slightly, but the meaning remained relatively the same. He ended his discussion on goals and means much as he did in the earlier version on the paper, except for the fact that he credited the term anomie to [[Emile Durkheim]]. In a footnote he traced the origin of the word to its first use in the late sixteenth century. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The second large expansion of Merton’s original work can be noticed in the typology of individual adaptations in situations of anomie. Under the ''Conformity'' adaptation he added a further explanation of society and its functions in his model. He stated that unless there is a deposit of shared values by individuals, there exists nothing but social relations, no society. He alludes to the fact that this may be the case within society (Merton 1949, p. 236). | |

| − | |||

| − | Merton | + | In describing the adaptation of ''Innovation'', Merton further develops the proposition that an individual who has not properly internalized the appropriate means for arriving at the sought after goal may choose such an avenue of relief. He also draws upon the discipline of Psychology in asserting that a person who has a great deal of emotional investment in the culturally accepted goal may be unusually willing to take risk in the hopes achieving the desired end. At this point Merton inserts ideas contained at the end of the original work under the section on ''Innovation''. |

| − | == | + | == Social Theory and Social Structure== |

| − | + | In 1957 Robert Merton published another revised paper under the title of “Social Structure and Anomie” as a chapter in his book ''Social Theory and Social Structure''. The work features the addition of several more examples in the discussion of the wide spread effects of the American Dream. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The chapter entitled “''Continuities in the Theory of Social Structure and Anomie''” is a further clarification of the components of his theory and a response to several criticisms it has received. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | As previously mentioned, it was Durkheim’s theory of anomie that inspired Merton’s theory of the same name. However, there is a '''fundamental difference between the theories and the direction in which they work'''. Merton, for the most part, accepted Durkheim’s concept of anomie and its meaning of a normless state of society. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | However, he took the concept in another direction. Merton saw a disjunction between culturally devised goals and accepted means of achieving the desired ends while Durkheim theorized that if the human appetite for goals was not regulated and became limitless, anomie would ensue, and from anomie, strain would emerge. Such strain would manifest itself in a variety of forms, one of which could be deviant behavior. | |

| − | + | So while both Durkheim and Merton are considered anomie theorists, they differ significantly in their outlooks. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | While Merton’s anomie theory is structurally different from that of Durkheim, it can be credited with drawing attention to the anomie theory in America. Merton’s theory also could be cited for placing emphasis on the need for development of future anomie and strain theories, such as those by Richard [[Cloward]], Lloyd [[Ohlin]] and Albert [[Cohen]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | It has been suggested that some of Merton’s ideas resulted in several programs in the United States during the 1960’s. Programs dealing with strategies such as affirmative action and equal opportunity, along race and gender lines are keeping with the ideas of the anomie perspective. A particular program that emerged during the Kennedy administration called “Mobilization for Youth” has been specifically credited to Merton. | |

| − | + | ==Strain theory== | |

| + | The measure of 'monetary success' ( in Merton 1938 ) is conveniently indefinite and relative. | ||

| − | + | "...''At each income level ... Americans want just about twenty-five per cent more... but of course this 'just a bit more' continues to operate once it is obtained''..."( Merton 1959, p.139 ), and: | |

| − | |||

| − | + | “... ''contemporary American culture continues to be characterised by a heavy emphasis on wealth as a basic symbol of success, without a corresponding emphasis upon the legitimate avenues on which to march toward this goal.'' ….( ibid. p. 140). | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Robert K. Merton borrowed Durkheim's concept of anomie to form his own theory, called “'''Strain Theory'''” (Merton 1938 ). It differs somewhat from Durkheim's in that Merton argued that the real problem is not created by a sudden social change, as Durkheim proposed, but rather by a social structure that holds out the same goals to all its members without giving them equal means to achieve them. It is this lack of integration between what the culture calls for and what the structure permits that causes deviant behaviour. Deviance then is a symptom of the social structure. Merton borrowed Durkheim's notion of anomie to describe the breakdown of the normative system. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Merton's theory does not focus upon crime as such, but rather upon various acts of deviance, which may be understood to lead to criminal behaviour. Merton notes that there are certain goals which are strongly emphasised by society. Society emphasises certain means to reach those goals (such as education, hard work, etc.,) However, not everyone has the equal access to the legitimate means to attain those goals. The stage then is set for anomie. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Merton then presents five modes of adapting to strain caused by the restricted access to socially approved goals and means. He did not mean that everyone who was denied access to society's goals became deviant. Rather the response, or modes of adaptation, depend on the individual's attitudes toward cultural goals and the institutional means to attain them. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

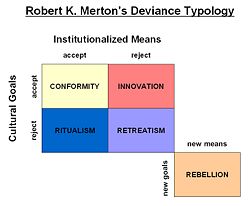

[[Image:Mertons social strain theory.jpg|thumb|right|250 px|Merton's structural-functional idea of deviance and anomie.]] | [[Image:Mertons social strain theory.jpg|thumb|right|250 px|Merton's structural-functional idea of deviance and anomie.]] | ||

The term [[anomie]], derived from [[Emile Durkheim]], for Merton means: a discontinuity between cultural goals and the legitimate means available for reaching them. Applied to the [[United States]] he sees the [[American dream]] as an emphasis on the goal of monetary success but without the corresponding emphasis on the legitimate avenues to march toward this goal. This leads to a considerable amount of (the Parsonian term of) [[deviance]]. This theory is commonly used in the study of [[criminology]] (specifically the [[strain theory]]). | The term [[anomie]], derived from [[Emile Durkheim]], for Merton means: a discontinuity between cultural goals and the legitimate means available for reaching them. Applied to the [[United States]] he sees the [[American dream]] as an emphasis on the goal of monetary success but without the corresponding emphasis on the legitimate avenues to march toward this goal. This leads to a considerable amount of (the Parsonian term of) [[deviance]]. This theory is commonly used in the study of [[criminology]] (specifically the [[strain theory]]). | ||

| Line 91: | Line 96: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | Definition of the terms in the graph : | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Conformity is the most common mode of adaptation. Individuals accept both the goals as well as the prescribed means for achieving those goals. Conformists will accept, though not always achieve, the goals of society and the means approved for achieving them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Innovation; individuals who adapt through innovation accept societal goals but have few legitimate means to achieve those goals, thus they innovate (design) their own means to get ahead. The means to get ahead may be through robbery, embezzlement or other such criminal acts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Ritualism; in ritualism, the third adaptation, individuals abandon the goals they once believed to be within their reach and dedicate themselves to their current lifestyle. They play by the rules and have a daily safe routine. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Retreatism is the adaptation of those who give up not only the goals but also the means. They often retreat into the world of alcoholism and drug addiction. They escape into a non-productive, non-striving lifestyle. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Rebellion; the final adaptation, rebellion, occurs when the cultural goals and the legitimate means are rejected. Individuals create their own goals and their own means, by protest or revolutionary activity. | ||

| + | |||

===Sociology of science=== | ===Sociology of science=== | ||

| Line 103: | Line 120: | ||

He introduced many relevant concepts to the field, among them '[[obliteration by incorporation]]' (when a concept becomes so popularized that its inventor is forgotten) and '[[Multiple (sociology)|multiples]]' (theory about independent similar discoveries). | He introduced many relevant concepts to the field, among them '[[obliteration by incorporation]]' (when a concept becomes so popularized that its inventor is forgotten) and '[[Multiple (sociology)|multiples]]' (theory about independent similar discoveries). | ||

| − | == | + | == Legacy== |

| − | + | Merton has received many national and international honors for his research. He was one of the first sociologists elected to the [[National Academy of Sciences]] and the first American sociologist to be elected a foreign member of the [[Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences]] and a [[Corresponding Fellow]] of the [[British Academy]]. He was also a member of the [[American Philosophical Society]], the [[American Academy of Arts and Sciences]], which awarded him its [[Parsons Prize]], the [[National Academy of Education]] and [[Academica Europaea]].[http://www.columbia.edu/cu/record/archives/vol20/vol20_iss2/record2002.13.html] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ==References== | + | He received a [[Guggenheim Fellowship]] in 1962 and was the first sociologist to be named a [[MacArthur Fellow]] (1983-88). More than 20 universities awarded him [[honorary degree]]s, including Harvard, Yale, Columbia and Chicago, and, abroad, the Universities of Leyden, Wales, Oslo and Kraków, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Oxford.[http://www.columbia.edu/cu/record/archives/vol20/vol20_iss2/record2002.13.html] |

| − | * | + | |

| − | * Robert Merton, | + | In [[1994]], Merton was awarded the US [[National Medal of Science]] for his work in the field[http://www.columbia.edu/cu/record/archives/vol20/vol20_iss2/record2002.13.html]. He was the first sociologist to receive the prize. |

| − | * | + | |

| + | == References == | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Calhoun, C., "[http://www.asanet.org/footnotes/mar03/indextwo.html , Remembered]," ''Footnotes'' (an internet website), March 2003. | ||

| + | *Merton, Robert K. “Social Structure and Anomie,” American Sociological Review 3, 1938, pp. 672-682 | ||

| + | *Merton, Robert K. “Social Structure and Anomie: Revisions and Extensions”, pp. 226-257; in: The Family, edited by Ruth Anshen, Harper Brothers, New York, 1949 | ||

| + | *Merton, Robert K. ,Social Theory and Social Structure rev. ed. Glencoe: Free Press 1957 | ||

| + | *Merton, Robert K.. “Social Conformity, Deviation, and Opportunity-Structures: A Comment on the Contributions of Dubin and Cloward.” American Sociological Review 24, 1959, pp.177-189 | ||

| + | *Robert K. Merton, The Sociology of Science, 1973 | ||

| + | *Robert K. Merton, Sociological Ambivalence, 1976 | ||

| + | *Robert K. Merton, On the Shoulders of Giants; in: Tristram Shandy|Shandean Postscript, 1985 | ||

| + | *[http://www.pupress.princeton.edu/titles/7576.html The Travels and Adventures of Serendipity: A Study in Sociological Semantics and the Sociology of Science, 2004] | ||

| + | *Sarton, G., Episodic Reflections by an Unruly Apprentice, Isis, 76, 1985, pp. 470-486. | ||

| + | *Sztompka, P.,Robert K. Merton, in: Blackwell Companion to Major Contemporary Social Theorists, [[George Ritzer]] (ed.), Blackwell Publishing, 2003, ISBN 140510595X [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN140510595X&id=xYPMCNQxLzsC&pg=PA12&lpg=PA12&q=merton&vq=merton&dq=140510595X&sig=rbgH_vzBs5ImX5FkxCrUix5uck8 Google Print, p.12-33] | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| Line 121: | Line 147: | ||

*[http://www.garfield.library.upenn.edu/merton/list.html Merton Bibliography] | *[http://www.garfield.library.upenn.edu/merton/list.html Merton Bibliography] | ||

*[http://www.mdx.ac.uk/www/study/xmer.htm Extracts from Merton] | *[http://www.mdx.ac.uk/www/study/xmer.htm Extracts from Merton] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

* [http://www.as.ua.edu/ant/Faculty/murphy/ecologic.htm ANTHROPOLOGICAL THEORIES: A GUIDE PREPARED BY STUDENTS FOR STUDENTS Dr. M.D. Murphy] | * [http://www.as.ua.edu/ant/Faculty/murphy/ecologic.htm ANTHROPOLOGICAL THEORIES: A GUIDE PREPARED BY STUDENTS FOR STUDENTS Dr. M.D. Murphy] | ||

* [http://www.diligio.com/notes26.htm THE UNANTICIPATED CONSEQUENCES OF HUMAN ACTION: A Synoposis of the Structure-Functional Theories of Robert K. Merton], Diligio, 2000 | * [http://www.diligio.com/notes26.htm THE UNANTICIPATED CONSEQUENCES OF HUMAN ACTION: A Synoposis of the Structure-Functional Theories of Robert K. Merton], Diligio, 2000 | ||

* [http://www.faculty.rsu.edu/~felwell/TheoryWeb/Merton.htm Merton, Robert K. 1957. Social Theory and Social Structure, revised and enlarged edition. New York: Free Press of Glencoe.] Excerpts, selected by [[Frank Elwell]] | * [http://www.faculty.rsu.edu/~felwell/TheoryWeb/Merton.htm Merton, Robert K. 1957. Social Theory and Social Structure, revised and enlarged edition. New York: Free Press of Glencoe.] Excerpts, selected by [[Frank Elwell]] | ||

* [http://www.angelfire.com/or/sociologyshop/manlat.html Manifest and Latent Functions] Excerpt from Invitation to Sociology by [[Peter L. Berger]], pp. 40-41 (NY: Doubleday (Anchor Books), 1963) | * [http://www.angelfire.com/or/sociologyshop/manlat.html Manifest and Latent Functions] Excerpt from Invitation to Sociology by [[Peter L. Berger]], pp. 40-41 (NY: Doubleday (Anchor Books), 1963) | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Credit2|Robert_K._Merton|65806124|Manifest_and_latent_functions_and_dysfunctions|56887091|}} | {{Credit2|Robert_K._Merton|65806124|Manifest_and_latent_functions_and_dysfunctions|56887091|}} | ||

Revision as of 23:39, 25 September 2006

Robert King Merton (July 4, 1910 – February 23, 2003, born Meyer R. Schkolnick to immigrant parents) was a distinguished American sociologist perhaps best known for having coined the phrase "self-fulfilling prophecy." He also coined many other phrases that have gone into everyday use, such as "role model" and "unintended consequences". He spent most of his career teaching at Columbia University, where he attained the rank of University Professor.

The dissertation, a quantitative social history of the development of science in seventeenth-century England, reflected this interdisciplinary committee.[Merton, 1985]

Biography

Robert K. Merton was born in working class Jewish Eastern European immigrants family, on July 4, 1910, in Philadelphia. Educated in the South Philadelphia High School, he became a frequent visitor of the nearby Andrew Carnegie Library, The Academy of Music, Central Library, Museum of Arts and other cultural and educational centres. He started his sociological career under the guidance of George E. Simpson in Temple College (1927-1931), and Pitrim A. Sorokin in Harvard University (1931-1936).[Sztompka, 2003].

It is a popular misconception that Robert K. Merton was one of Talcott Parsons’ students. Parsons was only a junior member of his dissertation committee, the others being Pitirim Sorokin, Carle C. Zimmermanm and the historian of science, George Sarton. Merton was, on the other hand, heavily influenced by Pitirim Sorokin, who tried to balance large-scale theorizing with a strong interest in empirical research and statistical studies. Sorokin and Paul Lazarsfeld influenced Merton to occupy himself with middle-range theories.

He taught at Harvard until 1939, when he became professor and chairman of the Department of Sociology at Tulane University. In 1941 he joined the Columbia University faculty, becoming Giddings Professor of Sociology in 1963. He was named to the University's highest academic rank, University Professor, in 1974 and became Special Service Professor upon his retirement in 1979, a title reserved by the Trustees for emeritus faculty who "render special services to the University."

In recognition of his lasting contributions to scholarship and the University, Columbia established the Robert K. Merton Professorship in the Social Sciences in 1990. He was associate director of the University's Bureau of Applied Social Research from 1942 to 1971. He was an adjunct faculty member at Rockefeller University and was also the first Foundation Scholar at the Russell Sage Foundation.[1] He withdrew from teaching in 1984.[Sztompka, 2003]

Merton was married twice, including to fellow sociologist Harriet Zuckerman. He has two sons and two daughters from the first marriage, including Robert Carhart Merton, winner of the 1997 Nobel Prize in economics. He died in 2003.

Works

Social structure and anomie

"Social structure and anomie" in 1938 edition

Robert Merton set out to expand upon the concept of Durkheim’s anomie. Merton began by stating that there are two elements of social and cultural structure. The first structure is culturally assigned goals and aspirations (Merton 1938, p. 672). These are the things that all individuals should want and expect out of life. Including success, money, material things, etc. The second aspect of the social structure defines the acceptable mode for achieving the goals and aspirations set by society (Merton 1938, p. 673).

This is the appropriate way that people get what they want and expect out of life. Examples include obeying laws and societal norms, seeking an education and hard work. In order for society to maintain a normative function there must be a balance between aspirations and means in which to fulfill such aspirations (Merton 1938, pp. 673-674).

According to Merton, balance would occur as long as the individual felt that he was achieving the culturally desired goal by conforming to the “institutionally accepted mode of doing so” (Merton, 1938, p. 674).

In other words, there must be an intrinsic payoff, an internal satisfaction that one is playing by the rules and there must also be an extrinsic payoff, achieving their goals. It is also important that the culturally desired goals be achievable by legitimate means for all social classes. If goals are not equally achievable through an accepted mode, then illegitimate means might be used to achieve the same goal.

"Social Structure and anomie" in 1949 edition

Merton changed the definition of cultural aspirations to include those goals held out as legitimate objectives for all or for diversely located members of society. In his explanation of means he reworded the definition slightly, but the meaning remained relatively the same. He ended his discussion on goals and means much as he did in the earlier version on the paper, except for the fact that he credited the term anomie to Emile Durkheim. In a footnote he traced the origin of the word to its first use in the late sixteenth century.

The second large expansion of Merton’s original work can be noticed in the typology of individual adaptations in situations of anomie. Under the Conformity adaptation he added a further explanation of society and its functions in his model. He stated that unless there is a deposit of shared values by individuals, there exists nothing but social relations, no society. He alludes to the fact that this may be the case within society (Merton 1949, p. 236).

In describing the adaptation of Innovation, Merton further develops the proposition that an individual who has not properly internalized the appropriate means for arriving at the sought after goal may choose such an avenue of relief. He also draws upon the discipline of Psychology in asserting that a person who has a great deal of emotional investment in the culturally accepted goal may be unusually willing to take risk in the hopes achieving the desired end. At this point Merton inserts ideas contained at the end of the original work under the section on Innovation.

Social Theory and Social Structure

In 1957 Robert Merton published another revised paper under the title of “Social Structure and Anomie” as a chapter in his book Social Theory and Social Structure. The work features the addition of several more examples in the discussion of the wide spread effects of the American Dream.

The chapter entitled “Continuities in the Theory of Social Structure and Anomie” is a further clarification of the components of his theory and a response to several criticisms it has received.

As previously mentioned, it was Durkheim’s theory of anomie that inspired Merton’s theory of the same name. However, there is a fundamental difference between the theories and the direction in which they work. Merton, for the most part, accepted Durkheim’s concept of anomie and its meaning of a normless state of society.

However, he took the concept in another direction. Merton saw a disjunction between culturally devised goals and accepted means of achieving the desired ends while Durkheim theorized that if the human appetite for goals was not regulated and became limitless, anomie would ensue, and from anomie, strain would emerge. Such strain would manifest itself in a variety of forms, one of which could be deviant behavior.

So while both Durkheim and Merton are considered anomie theorists, they differ significantly in their outlooks.

While Merton’s anomie theory is structurally different from that of Durkheim, it can be credited with drawing attention to the anomie theory in America. Merton’s theory also could be cited for placing emphasis on the need for development of future anomie and strain theories, such as those by Richard Cloward, Lloyd Ohlin and Albert Cohen.

It has been suggested that some of Merton’s ideas resulted in several programs in the United States during the 1960’s. Programs dealing with strategies such as affirmative action and equal opportunity, along race and gender lines are keeping with the ideas of the anomie perspective. A particular program that emerged during the Kennedy administration called “Mobilization for Youth” has been specifically credited to Merton.

Strain theory

The measure of 'monetary success' ( in Merton 1938 ) is conveniently indefinite and relative.

"...At each income level ... Americans want just about twenty-five per cent more... but of course this 'just a bit more' continues to operate once it is obtained..."( Merton 1959, p.139 ), and:

“... contemporary American culture continues to be characterised by a heavy emphasis on wealth as a basic symbol of success, without a corresponding emphasis upon the legitimate avenues on which to march toward this goal. ….( ibid. p. 140).

Robert K. Merton borrowed Durkheim's concept of anomie to form his own theory, called “Strain Theory” (Merton 1938 ). It differs somewhat from Durkheim's in that Merton argued that the real problem is not created by a sudden social change, as Durkheim proposed, but rather by a social structure that holds out the same goals to all its members without giving them equal means to achieve them. It is this lack of integration between what the culture calls for and what the structure permits that causes deviant behaviour. Deviance then is a symptom of the social structure. Merton borrowed Durkheim's notion of anomie to describe the breakdown of the normative system.

Merton's theory does not focus upon crime as such, but rather upon various acts of deviance, which may be understood to lead to criminal behaviour. Merton notes that there are certain goals which are strongly emphasised by society. Society emphasises certain means to reach those goals (such as education, hard work, etc.,) However, not everyone has the equal access to the legitimate means to attain those goals. The stage then is set for anomie.

Merton then presents five modes of adapting to strain caused by the restricted access to socially approved goals and means. He did not mean that everyone who was denied access to society's goals became deviant. Rather the response, or modes of adaptation, depend on the individual's attitudes toward cultural goals and the institutional means to attain them.

The term anomie, derived from Emile Durkheim, for Merton means: a discontinuity between cultural goals and the legitimate means available for reaching them. Applied to the United States he sees the American dream as an emphasis on the goal of monetary success but without the corresponding emphasis on the legitimate avenues to march toward this goal. This leads to a considerable amount of (the Parsonian term of) deviance. This theory is commonly used in the study of criminology (specifically the strain theory).

| Cultural goals | Institutionalized means | Modes of adaptation |

|---|---|---|

| + | + | Conformity |

| + | - | Innovation |

| - | + | Ritualism |

| - | - | Retreatism |

| ± | ± | Rebellion |

Definition of the terms in the graph :

- Conformity is the most common mode of adaptation. Individuals accept both the goals as well as the prescribed means for achieving those goals. Conformists will accept, though not always achieve, the goals of society and the means approved for achieving them.

- Innovation; individuals who adapt through innovation accept societal goals but have few legitimate means to achieve those goals, thus they innovate (design) their own means to get ahead. The means to get ahead may be through robbery, embezzlement or other such criminal acts.

- Ritualism; in ritualism, the third adaptation, individuals abandon the goals they once believed to be within their reach and dedicate themselves to their current lifestyle. They play by the rules and have a daily safe routine.

- Retreatism is the adaptation of those who give up not only the goals but also the means. They often retreat into the world of alcoholism and drug addiction. They escape into a non-productive, non-striving lifestyle.

- Rebellion; the final adaptation, rebellion, occurs when the cultural goals and the legitimate means are rejected. Individuals create their own goals and their own means, by protest or revolutionary activity.

Sociology of science

Merton carried out extensive research into the sociology of science, developing the Merton Thesis explaining some of the causes of the scientific revolution, and the "Mertonian norms" of science. This is a set of ideals that scientists should strive to attain, specifically:

- Communalism - science is an open community;

- Universalism - science does not discriminate;

- Disinterestedness - science favors an outward objectivity;

- Organized Skepticism - all ideas must be tested and are subject to community scrutiny;

He introduced many relevant concepts to the field, among them 'obliteration by incorporation' (when a concept becomes so popularized that its inventor is forgotten) and 'multiples' (theory about independent similar discoveries).

Legacy

Merton has received many national and international honors for his research. He was one of the first sociologists elected to the National Academy of Sciences and the first American sociologist to be elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and a Corresponding Fellow of the British Academy. He was also a member of the American Philosophical Society, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, which awarded him its Parsons Prize, the National Academy of Education and Academica Europaea.[2]

He received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1962 and was the first sociologist to be named a MacArthur Fellow (1983-88). More than 20 universities awarded him honorary degrees, including Harvard, Yale, Columbia and Chicago, and, abroad, the Universities of Leyden, Wales, Oslo and Kraków, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Oxford.[3]

In 1994, Merton was awarded the US National Medal of Science for his work in the field[4]. He was the first sociologist to receive the prize.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Calhoun, C., ", Remembered," Footnotes (an internet website), March 2003.

- Merton, Robert K. “Social Structure and Anomie,” American Sociological Review 3, 1938, pp. 672-682

- Merton, Robert K. “Social Structure and Anomie: Revisions and Extensions”, pp. 226-257; in: The Family, edited by Ruth Anshen, Harper Brothers, New York, 1949

- Merton, Robert K. ,Social Theory and Social Structure rev. ed. Glencoe: Free Press 1957

- Merton, Robert K.. “Social Conformity, Deviation, and Opportunity-Structures: A Comment on the Contributions of Dubin and Cloward.” American Sociological Review 24, 1959, pp.177-189

- Robert K. Merton, The Sociology of Science, 1973

- Robert K. Merton, Sociological Ambivalence, 1976

- Robert K. Merton, On the Shoulders of Giants; in: Tristram Shandy|Shandean Postscript, 1985

- The Travels and Adventures of Serendipity: A Study in Sociological Semantics and the Sociology of Science, 2004

- Sarton, G., Episodic Reflections by an Unruly Apprentice, Isis, 76, 1985, pp. 470-486.

- Sztompka, P.,Robert K. Merton, in: Blackwell Companion to Major Contemporary Social Theorists, George Ritzer (ed.), Blackwell Publishing, 2003, ISBN 140510595X Google Print, p.12-33

External links

- A website on Merton

- Review materials for studying Robert King Merton

- The Unanticipated Consequences of Purposive Social Action

- Merton Bibliography

- Extracts from Merton

- ANTHROPOLOGICAL THEORIES: A GUIDE PREPARED BY STUDENTS FOR STUDENTS Dr. M.D. Murphy

- THE UNANTICIPATED CONSEQUENCES OF HUMAN ACTION: A Synoposis of the Structure-Functional Theories of Robert K. Merton, Diligio, 2000

- Merton, Robert K. 1957. Social Theory and Social Structure, revised and enlarged edition. New York: Free Press of Glencoe. Excerpts, selected by Frank Elwell

- Manifest and Latent Functions Excerpt from Invitation to Sociology by Peter L. Berger, pp. 40-41 (NY: Doubleday (Anchor Books), 1963)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.