Zhang Qian

| Zhang Qian 張騫 |

|---|

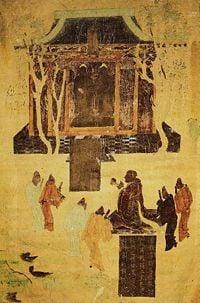

Zhang Qian taking leave from emperor Han Wudi, for his expedition to Central Asia from 138 to 126 B.C.E., Mogao Caves mural, 618-712 C.E.

|

| Born |

| 195 B.C.E. Hanzhong, Shaanxi, China |

| Died |

| 114 B.C.E. China |

Zhang Qian or Chang Ch'ien (張|張, 騫|騫) was an imperial envoy during the second century B.C.E., during the time of the Han Dynasty ( 漢朝). In 138 B.C.E., he was dispatched by Emperor Wu of Han ( 漢武帝), to negotiate an alliance with Yuexhi against the Xiongnu. He was captured by the Xiongnu, who detained him for ten years and gave him a wife. After his escape, he continued his mission to the Yuezhi, but found them at peace with the Xiongnu. He remained with the Yuezhi for a year, collecting information about the surrounding states and people. On his way back to China, he was again captured and detained by the Xiongnu, but escaped during the political unrest caused by the death of their king. In 125 B.C.E., he returned to China with detailed reports for the Emperor which showed that sophisticated civilizations existed to the West, with which China could advantageously develop relations.

Zhang was the first official diplomat to bring back reliable information about Central Asia to the Chinese imperial court. His reports initiated the Chinese colonization and conquest of the region now known as Xinjiang (新疆). Many Chinese missions were sent out throughout the end of the second century B.C.E. and the first century B.C.E., and commercial relations between China and Central, as well as Western, Asia flourished. By 106 B.C.E., the Silk Road was an established thoroughfare. Zhang Qian's accounts of his explorations of Central Asia are detailed in the Early Han historical chronicles "Shiji" (史記, or "Records of the Great Historian"), compiled by Sima Qian (司馬遷) in the first century B.C.E. .

First Embassy to the West

Zhang Qian was born in 195 B.C.E. in present day Hanzhong, Shaanxi, at the border of northeastern Sichuan ( 四川). He entered the capital, Chang'an(長安 ), between 140 B.C.E. and 134 B.C.E. as a gentleman (郎), serving Emperor Wu of Han China. At that time the Xiongnu (匈奴)tribes controlled modern Inner Mongolia and dominated much of modern Xiyu (西域 "Western Regions").

Around 177 B.C.E., led by one of Modu's tribal chiefs, the Xiongnu had invaded Yuezhi territory in the Gansu region and achieved a devastating victory. Modu boasted in a letter to the Han emperor that due to "the excellence of his fighting men, and the strength of his horses, he has succeeded in wiping out the Yuezhi, slaughtering or forcing to submission every number of the tribe." The son of Modu, Jizhu, subsequently killed the king of the Yuezhi and, in accordance with nomadic traditions, "made a drinking cup out of his skull" (Shiji 123; Watson 1961, 231). The Han emperor believed that, after being treated so harshly, the Yuezhi would be ready to form an alliance with the Han dynasty for the purpose of overcoming the Xiongnu. In 138 B.C.E. the Han court despatched Zhang Qian to the Western Regions with a delegation of over one hundred, accompanied by a Xiongnu guide named Ganfu (甘父) or Tangyi Fu, a slave owned by the Chinese family Tangyi (堂邑氏). The objective of Zhang Qian's first mission was to seek a military alliance with the Greater Yuezhi ( 大月氏), in modern Tajikistan.

En route, Zhang Qian and his delegation were captured by the Xiongnu and detained for ten years. They were well treated and gained the trust of the Xiongnu leader; Zhian Qian was given a wife, with whom he had a son. After 12 years of captivity, he finally escaped, together with his wife and his faithful slave, and continue on his mission to reach the Yuezhi, to the north of Bactria. When Zhang finally arrived in Yuezhi territory in 138 B.C.E., he found that the Yuezhi were too settled to desire war against the Xiongnu. He spent about one year in Yuezhi and Bactrian territory, documenting their cultures, lifestyles and economy, before returning to China. He sent his assistant to visit Fergana (Uzbekistan), Bactria (Afghanistan), and Sogdiana (west Turkestan, now in Uzbekistan), and gathered information on Parthia, India, and other states from merchants and other travelers.

Return to China

On his return trip to China he was captured by Tibetan tribes allied with the Xiongnu, who again spared his life because they valued his sense of duty and composure in the face of death. Two years later, the Xiongnu leader died and in the midst of chaos and infighting Zhang Qian escaped. Of the original delegation, only Zhang Quian and the faithful slave completed the journey. Zhang Quian returned to China accompanied by his wife. Zhang Quian was given a high position in the imperial bureaucracy, and the slave was ennobled and given the title, 'Lord Who Carries Out His Mission'.

Zhang Qian returned in 125 B.C.E. with detailed reports for the Emperor which showed that sophisticated civilizations existed to the West, with which China could advantageously develop relations. The Shiji relates that "the emperor learned of the Dayuan, Daxia, Anxi, and the others, all great states rich in unusual products whose people cultivated the land and made their living in much the same way as the Chinese. All these states, he was told, were militarily weak and prized Han goods and wealth." (Shiji, 123, trans. Burton Watson).

In 119 B.C.E. Zhang Quian set out on a second, more organized expedition, a trade mission to the Wu-sun( (烏孫) people, an Indo-European tribe living in the Ili Valley north of the Tarim Basin. The expedition was successful and led to trade between China and Persia.

Zhang Qian's Report

The report of Zhang Qian's travels is quoted extensively in the Chinese historic chronicles "Records of the Great Historian" (Shiji) written by Sima Qian in the first century B.C.E.. Zhang Qian himself visited the kingdom of Dayuan in Ferghana, the territories Yuezhi in Transoxonia, the Bactrian country of Daxia with it remnants of Greco-Bactrian rule, and Kangju (康居). He also made reports on neighbouring countries that he did not visit, such as Anxi (Parthia), Tiaozhi (Mesopotamia), Shendu (India), and the Wusun.

Dayuan (Ferghana)

Zhang Qian began with a report on the first country he visited after his captivity among the Xiongnu, Dayuan( a people of Ferghana, in eastern Uzbekistan), west of the Tarim Basin. He described them as sophisticated urban dwellers, on the same footing with the Parthian and the Bactrians. The name Dayuan (meaning Great Yuan), may be a transliteration of the word Yona used to designate Greeks, who occupied the region from the fourth to the second century B.C.E..

- "Dayuan lies southwest of the territory of the Xiongnu, some 10,000 li (5,000 kilometers) directly west of China. The people are settled on the land, plowing the fields and growing rice and wheat. They also make wine out of grapes. The people live in houses in fortified cities, there being some seventy or more cities of various sizes in the region. The population numbers several hundred thousand" (Shiji, 123, trans. Burton Watson).

Yuezhi

After obtaining the help of the king of Dayuan, Zhang Qian went southwest to the territory of the Yuezhi, with whom he was supposed to obtain a military alliance against the Xiongnu.

- "The Great Yuezhi live some 2,000 or 3,000 li (1,000 or 1,500 kilometers) west of Dayuan, north of the Gui (Oxus) river. They are bordered to the south by Daxia (Bactria), on the west by Anxi (Parthia), and on the north by Kangju (康居). They are a nation of nomads, moving place to place with their herds and their customs are like those of the Xiongnu. They have some 100,000 or 200,000 archer warriors." (Shiji, 123, trans. Burton Watson).

Zhang Qian also describes the origins of the Yuezhi, explaining they came from the eastern part of the Tarim Basin, significant information which has encouraged historians to connect them to the Caucasoid mummies, as well as to the Indo-European-speaking Tocharians who have been identified as originating from precisely the same area:

- "The Yuezhi originally lived in the area between the Qilian or Heavenly Mountains (Tian Shan) and Dunhuang, but after they were defeated by the Xiongnu they moved far away to the west, beyond Dayuan (Ferghana), where they attacked the people of Daxia (Bactria) and set up the court of their king on the northern bank of the Gui (Oxus) river." (Shiji, 123, trans. Burton Watson).

A smaller group of Yuezhi, the "Little Yuezhi" were not able to follow the exodus and reportedly found refuge among the "Qiang barbarians" (Tibetans).

Daxia (Bactria)

Zhang Qian reported that Bactria had a different culture from the surrounding regions, because a conqueror, Alexander the Great, had come there from the west. As a result, Bactria had Greek coins, Greek sculpture and a Greek script. Zhang Qian's presence there was the first recorded interaction between the civilizations of the Far East and of the Mediterranean. Zhang Qian probably witnessed the last period of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom( today's northern Afghanistan and parts of Central Asia), as it was being subjugated by the nomad Yuezhi. Only small powerless chiefs remained, who were apparently vassals to the Yuezhi horde. Their civilization was urban, almost identical to the civilizations of Parthia and Dayuan, and the population was numerous.

In Bactria, Zhang Qian found objects of bamboo and cloth made in southern China. He was told that they had been brought by merchants from a land to the southeast, situated on a great river, where the inhabitants rode elephants when they went into battle.

- "Daxia is situated over 2,000 li (1,000 kilometers) southwest of Dayuan (Ferghana), south of the Gui (Oxus) river. Its people cultivate the land, and have cities and houses. Their customs are like those of Dayuan. It has no great ruler but only a number of petty chiefs ruling the various cities. The people are poor in the use of arms and afraid of battle, but they are clever at commerce. After the Great Yuezhi moved west and attacked and conquered Daxia, the entire country came under their sway. The population of the country is large, numbering some 1,000,000 or more persons. The capital is Lanshi (Bactra) where all sorts of goods are bought and sold." (Shiji, 123, translation Burton Watson).

Shendu (India)

Zhang Qian also reported about the existence of India southeast of Bactria. The name Shendu comes from the Sanskrit word "Sindhu," used for the province of Sindh (now a province of Pakistan) by its local people. Sindh was one of the most advanced regions of India at the time. Although it was part of India, it had an autonomous government. Because of its coastal borders with Persia and the Arabian Sea, it invited great wealth from these regions. Parts of Northwestern India (modern Pakistan) were ruled by the Indo-Greek Kingdom at the time, which explains the reported cultural similarity between Bactria and India.

- "Southeast of Daxia is the kingdom of Shendu (India) ... Shendu, they told me, lies several thousand li southeast of Daxia (Bactria). The people cultivate the land and live much like the people of Daxia. The region is said to be hot and damp. The inhabitants ride elephants when they go in battle. The kingdom is situated on a great river (Indus)" (Shiji, 123, Zhang Qian quote, trans. Burton Watson).

Anxi (Parthia)

Zhang Qian clearly identified Parthia as an advanced urban civilization, like Dayuan (Ferghana) and Daxia (Bactria). The name "Anxi" is a transliterations of "Arsacid," the name of the Parthian dynasty.

- "Anxi is situated several thousand li west of the region of the Great Yuezhi. The people are settled on the land, cultivating the fields and growing rice and wheat. They also make wine out of grapes. They have walled cities like the people of Dayuan (Ferghana), the region contains several hundred cities of various sizes. The coins of the country are made of silver and bear the face of the king. When the king dies, the currency is immediately changed and new coins issued with the face of his successor. The people keep records by writing on horizontal strips of leather. To the west lies Tiaozhi (Mesopotamia) and to the north Yancai and Lixuan (Hyrcania)." (Shiji, 123, trans. Burton Watson).

Tiaozhi

Zhang Qian also reported on Mesopotamia, beyond Parthia, although in rather tenuous terms, because he was only able to report other's accounts.

- "Tiaozhi (Mesopotamia) is situated several thousand li west of Anxi (Parthia) and borders the Western Sea (Persian Gulf/Mediterranean?). It is hot and damp, and the people live by cultivating the fields and planting rice... The people are very numerous and are ruled by many petty chiefs. The ruler of Anxi (Parthia) gives orders to these chiefs and regards them as vassals." (Shiji, 123, trans. Burton Watson).

Kangju (康居) northwest of Sogdiana (粟特)

Zhang Qian also visited the area of Sogdiana( an ancient civilization of an Iranian people), home to the Sogdian nomads:

- "Kangju is situated some 2,000 li (1,000 kilometers) northwest of Dayuan (Bactria). Its people are nomads and resemble the Yuezhi in their customs. They have 80,000 or 90,000 skilled archer fighters. The country is small, and borders Dayuan. It acknowledges sovereignty to the Yuezhi people in the South and the Xiongnu in the East." (Shiji, 123, trans. Burton Watson).

Yancai 奄蔡 (Vast Steppe)

- "Yancai lies some 2,000 li (832 km) northwest of Kangju (centered on Turkestan (a city in the southern region of Kazakhstan) at Bei'tian). The people are nomads and their customs are generally similar to those of the people of Kangju. The country has over 100,000 archer warriors, and borders a great shoreless lake, perhaps what is known as the Northern Sea (Aral Sea, distance between Tashkent to Aralsk is about 866 km)" (Shiji, 123, trans. Burton Watson).

Development of East-West Contacts

Following Zhang Qian's embassy and report, commercial relations between China and Central as well as Western Asia flourished. Many Chinese missions were sent throughout the end of the second century B.C.E. and the first century B.C.E.. By 106 B.C.E., the Silk Road was an established thoroughfare:

- "The largest of these embassies to foreign states numbered several hundred persons, while even the smaller parties included over 100 members... In the course of one year anywhere from five to six to over ten parties would be sent out." (Shiji, trans. Burton Watson).

Many objects were soon exchanged, and traveled as far as Guangzhou( 廣州) (the modern capital of Guangdong Province in the southern part of the People's Republic of China.) in the East, as suggested by the discovery of a Persian box and various artifacts from Central Asia in the 122 B.C.E. tomb of the Chinese King Wen of Nanyue. New plants such as grapes and alfalfa, were introduced China as well as a superior breed of horse.

Murals in Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, an oasis in modern province of Gansu, China, depict the Emperor Han Wudi ( 漢武帝Emperor Wu of Han) (156-87 B.C.E.) worshipping Buddhist statues, explaining that they are "golden men brought in 120 B.C.E. by a great Han general in his campaigns against the nomads," although there is no other mention of Han Wudi worshipping the Buddha in Chinese historical literature.

China also sent a mission to Parthia, a civilization situated in the northeast of modern Iran, which was followed up by reciprocal missions from Parthian envoys around 100 B.C.E.:

- "When the Han envoy first visited the kingdom of Anxi (Parthia), the king of Anxi dispatched a party of 20,000 horsemen to meet them on the eastern border of the kingdom... When the Han envoys set out again to return to China, the king of Anxi dispatched envoys of his own to accompany them... The emperor was delighted at this." (Shiji, 123, trans. Burton Watson).

The Roman historian Florus describes the visit of numerous envoys, including Seres (Chinese), to the first Roman Emperor Augustus, who reigned between 27 B.C.E. and 14 C.E.:

- "Even the rest of the nations of the world which were not subject to the imperial sway were sensible of its grandeur, and looked with reverence to the Roman people, the great conqueror of nations. Thus even Scythians and Sarmatians sent envoys to seek the friendship of Rome. Nay, the Seres came likewise, and the Indians who dwelt beneath the vertical sun, bringing presents of precious stones and pearls and elephants, but thinking all of less moment than the vastness of the journey which they had undertaken, and which they said had occupied four years. In truth it needed but to look at their complexion to see that they were people of another world than ours." ("Cathey and the way thither," Henry Yule).

In 97 C.E., the Chinese general Ban Chao went as far west as the Caspian Sea with 70,000 men, secured Chinese control of the Tarim Basin region, and established direct military contacts with the Parthian Empire, also dispatching an envoy to Rome in the person of Gan Ying. Several Roman embassies to China soon followed from 166 C.E., and are officially recorded in Chinese historical chronicles.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Liu, Xinru, and Shaffer, Lynda. 2007. Connections across Eurasia: transportation, communication, and cultural exchange on the Silk Roads. Explorations in world history. Boston: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780072843514 ISBN 0072843519

- Quian, Sima (trans.). 1961. "Records of the Great Historian." Han Dynasty II, Sima Qian. Translated by Burton Watson, Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231081677

- Wood, Frances. 2002. The Silk Road: two thousand years in the heart of Asia. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520237862 ISBN 9780520237865

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.