Yoshida Kenko

Yoshida KenkŇć (Japanese: ŚźČÁĒįŚÖľŚ•Ĺ; Yoshida KenkŇć; 1283 - 1350) was a Japanese author and Buddhist monk. His major work, Tsurezuregusa (Essays in Idleness), is one of the most studied works of medieval Japanese literature; the consistent theme of the series of 243 essays is ‚Äúthe universal principle of change,‚ÄĚ one of the central ideas of Zen Buddhism. The work expresses the sentiment of "mono no aware" (the sorrow which results from the passage of things) found in the undercurrent of traditional Japanese culture since antiquity. Kenko described how the momentariness and transiency of an event or a process intensified its beauty.

According to legend, the monk Yoshida Kenko lived in a hermitage inside a Zen temple called Jyo‚ÄďGyo Ji (modern-day Yokohama City). Kenko wrote during the Muromachi and Kamakura periods. After the seventeenth century, Tsurezuregusa became a part of the curriculum in the Japanese educational system, and Kenko's views have held a prominent place in Japanese life ever since. Turezuregusa is one of the three representative Japanese classics, together with Hojoki by Kamo no Chomei (1212), and The Pillow Book (Makura no soshi) by Sei Shonagon(990).

Life and Work

KenkŇć was probably born in 1283, the son of a government official. His original name was "Urabe Kaneyoshi" (ŚćúťÉ®ŚÖľŚ•Ĺ). Urabe had been the official clan which served the Imperial Court by divining the future. Yoshida Kenko‚Äės family came from a long line of priests of the Yoshida Shinto shrine; for this reason he is called Yoshida Kenko instead of Urabe Kenko.

Kenko was born just two years after the second Mongol Invasion. One year after his birth, Hojo Tokimune, regent of the Kamakura shogunate, known for defending Japan against the Mongol forces, died. In 1336, the year that Kenko accomplished the 234 passages of Tsurezuregusa, Ashikaga Takauji founded the Muromachi shogunate and became the first shogun.

In his youth, Kenko became an officer of guards at the Imperial palace. Late in life he retired from public life, changed his name to Yoshida KenkŇć, and became a Buddhist monk and hermit. The reasons for this are unknown, but it has been conjectured that his transformation was caused by either his unhappy love for the daughter of the prefect of Iga Province, or his mourning over the death of Emperor Go-Uda.

Although he also wrote poetry and entered some poetry contests at the Imperial Court (his participation in 1335 and 1344 is documented), Kenko's enduring fame is based on Tsurezuregusa, his collection of 243 short essays, published posthumously. Although traditionally translated as "Essays in Idleness," a more accurate translation would be "Notes from Leisure Hours" or "Leisure Hour Notes." Themes of the essays include the beauty of nature, the transience of life, traditions, friendship, and other abstract concepts. The work was written in the zuihitsu ("follow-the-brush") style, a type of stream-of-consciousness writing that allowed the writer's brush to skip from one topic to the next, led only by the direction of thoughts. Some are brief remarks of only a sentence or two; others recount a story over a few pages, often with discursive personal commentary added.

The Tsurezuregusa was already popular in the fifteenth century, and was considered a classic from the seventeenth century onward. It is part of the curriculum in modern Japanese high schools, as well as internationally in some International Baccalaureate Diploma Program schools.

The Thought of Tsurezuregusa

The book was composed of random ideas written on small pieces of paper and stuck to the wall. After Kenko‚Äôs death, one of his friends compiled them into Tsurezuregusa. When the book is read through from beginning to end, the 243 essays appear to be consecutive. This was not the way they were written, nor did Kenko intend them as a series of consecutive arguments. The consistent theme of the essays is ‚Äúthe universal principle of change.‚ÄĚ Tsurezuregusa is also acclaimed for its treatment of aesthetics. For Kenko, beauty implied impermanence; the more short-lived a moment or object of beauty, the more precious he considered it to be.

"Tsure- zure" means ennui, the state of being bored and having nothing in particular to do, of being quietly lost in thought. However some interpretations say it means ‚Äúidleness‚ÄĚ or ‚Äúleisure.‚ÄĚ ‚ÄúGusa‚ÄĚ is a compound variant of the Japanese word ‚Äúkusa‚ÄĚ (grass). There are several popular classics, for example, the works of Shakespeare, which people want to read over and over, like a cow chewing its cud. Kenko‚Äôs work has been ‚Äúchewed‚ÄĚ over and over by the Japanese people throughout the centuries. The title suggests ‚Äúplayfulness;" Kenko write freely and playfully according to the flow of ideas in mind and emotional feelings.

During the middle ages of Japanese history, Yoshida Kenko already had a modern mind. Traditionally, a Japanese poet and person of literature adhered to old habits and traditions, but Kenko praised the attitude of indifference to these habits and traditions (especially in the description in the one-hundred-and-twelfth passage). In sixtieth passage Kenko admired the attitude of one high-ranking priest, who lived a poor life eating only taro roots. When this priest suddenly inherited a large fortune from his predecessor, he bought taro roots with his inheritance and continued to live on them. This priest spent his life that way, and even at a Court dinner party he never followed rules of formal etiquette. Although he was an unusual priest, the people never disliked him. Kenko praised his attitude as that of a person of virtue.

In the fifty-sixth and one-hundred-and-seventieth passages Kenko criticized contemporary human relationships. Kenko’s expression of his personal opinions was unusual in a feudal society. In the seventy-forth passage Kenko wrote:

the general people gathered as the ants did, and they hurried from the east to the west and from the south to the north. Some people belonged to the upper class, some did not. Some were old and some were young, some were greedy for wealth; eventually they all grew old and died. They did not know about “the universal principle of Change"."

When young people read Tsurezuregusa, they tend to regard it as a moralizing discourse. As people become older, the words of Tsurezuregusa take on a profound meaning. For example, in the one-hundred-and-ninety-first passage Kenko remarks that a situation can be understood better in the night (aged) than during the daytime (youth).

At the beginning of the seventeenth century (in the Keicho period, just between the end of the Shokuho period and the beginning of the Edo age), Tsurezuregusa was very popular. Matsunaga Teitoku gave public lectures on ‚ÄúTsurezuregusa.‚ÄĚ Hata Soha, a physician and poet, wrote an annotated edition of Tsurezuregusa. He summarized the essence of Tsurezuregusa, ‚ÄúMujo‚ÄĚ (mutability), from the viewpoints of Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism. In his writings on the process of change undergone by nature and things, Kenko well depicted "mono no aware" (the sorrow which results from the passage of things) in his unique literary style. The modern critic Kobayashi Hideo noted that Tsurezuregusa was a kind of literary piece that was "the first and probably the last‚ÄĚ in literary history.

In the world of Japanese literature, Yoshida Kenko during the Middle Ages, and Natsume Soseki during the Meiji era, pioneered the idea of individual self-awareness, and the attitude of freely expressing personal feelings and opinions.

Quotes

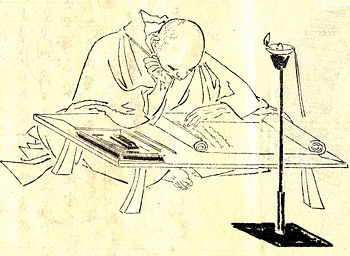

- "To sit alone in the lamplight with a book spread out before you hold intimate converse with men of unseen generations‚ÄĒsuch is pleasure beyond compare. "

- "Blossoms are scattered by the wind and the wind cares nothing, but the blossoms of the heart no wind can touch."

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chance, Linda H. Formless in Form: Kenko, 'Tsurezuregusa', and the Rhetoric of Japanese Fragmentary Prose. Stanford, Stanford University Press, 1997. ISBN 9780804730013

- Keene, Donald. Essays in Idleness: The Tsurezuregusa of Kenko. Columbia University Press, 1967.

- Yoshida, Kenko. et al. Idle Jottings: Zen Reflections from the Tsure-Zure Gusa of Yoshido Kenko. Associated Publishers Group , 1995. ISBN 9780951353608

- Yoshida, Kenko, and William H. Porter (trans.). The Miscellany of a Japanese Priest. Tuttle Publishing , 1973

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.