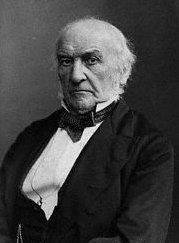

William Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone (December 29, 1809 â May 19, 1898) was a British Liberal Party statesman and prime minister of the United Kingdom (1868â1874, 1880â1885, 1886 and 1892â1894). He was a notable political reformer, known for his populist speeches, and was for many years the main political rival of Benjamin Disraeli.

Gladstone was famously at odds with Queen Victoria for much of his career. She once complained "He always addresses me as if I were a public meeting." Gladstone was known affectionately by his supporters as the "Grand Old Man" (Disraeli is said to have remarked that GOM should have stood for âGod's Only Mistakeâ) or "The People's William." He is still regarded as one of the greatest British prime ministers, with Winston Churchill and others citing Gladstone as their inspiration. A devout Anglican, after his 1874 defeat Gladstone considered leaving politics to enter the Christian ministry. He had a keen interest in theology and literature and was very widely-read.

Gladstone tried to tackle one of the most complex political issues of his day, the question of home rule for Ireland. Reforms during his administration included abolition of the sale of military commissions, the 1870 Education Act that made elementary education free for all children, and the extension of the number of people eligible to vote (1884), while his promotion of free trade overseas was intended to help avoid conflict and secure peace throughout the globe. He opposed the scramble for Africa and several wars as dishonorable, including the Second Afghan War and the Zulu War. He advocated lower taxes so that people would be more content, anticipating the more recent trend to repatriate services from the public to the private sector so that citizens can choose the providers they wish.

A man of deep moral convictions, Gladstone resigned from government in 1845 on a matter of conscience. However, his views also changed over time. In 1845, he disagreed with spending money on a Catholic seminary. Later, he supported the disestablishment of the Protestant Church of Ireland so that Catholics would not have to pay taxes to support Protestant clergy.

Early life

Born in Liverpool in 1809, Gladstone was the fourth son of the merchant Sir John Gladstones and his second wife, Anne MacKenzie Robertson. The final "s" was later dropped from the family surname. Although Gladstone was born and brought up in Liverpool and always retained a slight Lancashire accent, he was of Scottish descent on both his mother's and father's side of the family. Gladstone was educated at Eton College, and in 1828 matriculated at Christ Church, Oxford where he took classics and mathematics in order to obtain a double first-class degree despite the fact that he had no great interest in mathematics. In December 1831 after sitting for his final examinations, he learned that he had indeed achieved the double first he had long desired. Gladstone served as president of the Oxford Union debating society, where he developed a reputation as a fine orator, a reputation that later followed him into the House of Commons. At university Gladstone was a Tory and denounced Whig (Liberal) proposals for parliamentary reform.

He was first elected to Parliament in 1832 as Conservative MP for Newark. Initially he was a disciple of High Toryism, opposing the abolition of slavery and factory legislation. In 1838 he published a book, The State in its Relations with the Church, which argued that the goal of the state should be to promote and defend the interests of the Church of England. In 1839 he married Catherine Glynne, to whom he remained married until his death 59 years later.

In 1840, Gladstone began to rescue and rehabilitate London prostitutes, actually walking the streets of London himself and encouraging the women he encountered to change their ways. He continued this practice even after he'd been elected prime minister decades later.

Minister under Peel

Gladstone was re-elected in 1841. In September 1842 he lost the forefinger of his left hand in an accident while reloading a gun; thereafter he wore a glove or finger sheath (stall). In the second ministry of Robert Peel, he served as president of the Board of Trade (1843â1844). He resigned in 1845 over the issue of funding the Maynooth Seminary in Ireland, a matter of conscience for him (the seminary is Catholic).

In order to improve relations with Irish Catholics, Peel's government had proposed increasing the annual grant paid to the Seminary for training Catholic priests. Gladstone, who had previously argued in a book that a Protestant country should not pay money to other churches, supported the increase in the Maynooth grant and voted for it in Commons, but resigned rather than face charges that he'd compromised his principles to remain in office. After accepting Gladstone's resignation, Peel confessed to a friend, "I really have great difficulty sometimes in exactly comprehending what he means."

Gladstone returned to Peel's government as secretary of state for war and the colonies in December. The following year, Peel's government fell over the prime minister's repeal of the Corn Laws and Gladstone followed his leader into a course of separation from mainstream Conservatives. After Peel's death in 1850, Gladstone emerged as the leader of the Peelites in the House of Commons.

As chancellor he pushed to extend the free trade liberalizations in the 1840s and worked to reduce public expenditures, policies that, when combined with his moral and religious ideals, became known as "Gladstonian Liberalism." He was re-elected for the University of Oxford in 1847 and became a constant critic of Lord Palmerston.

In 1848 he also founded the Church Penitentiary Association for the Reclamation of Fallen Women. In May 1849 he began his most active "rescue work" with "fallen women" and met prostitutes late at night on the street, in his house, or in their houses, writing their names in a private notebook. He aided the House of Mercy at Clewer near Windsor, Berkshire (which exercised extreme in-house discipline) and spent much time arranging employment for ex-prostitutes. There is no evidence he ever actually used their services, and it is known that his wife supported these unconventional activities. In 1927, during a court case over published claims that he had had improper relationships with some of these women, the jury unanimously found that the evidence "completely vindicated the high moral character of the late Mr. W. E. Gladstone."

From 1849 until 1859, Gladstone is known to have drawn a picture of a whip in his diary, suggesting that he may have suffered temptation, either in the presence of the prostitutes or from "marginally salacious (published) material" he read (as Roy Jenkins has described it), and may have used self-flagellation as a means of self-regulation or repentance, a practice also adopted by Cardinal John Henry Newman and Edward Pusey.

Chancellor of the Exchequer

After visiting Naples in 1850, Gladstone began to support Neapolitan opponents of the Two Sicilies Bourbon rulers. In 1852, following the ascendance of Lord Aberdeen, as premier, head of a coalition of Whigs and Peelites, Gladstone became chancellor of the exchequer and unsuccessfully tried to abolish the income tax. Instead, he ended up raising it because of the Crimean War.

He served until 1855. Lord Stanley became prime minister in 1858, but Gladstone declined a position in his government, opting not to work with Benjamin Disraeli, then chancellor of the exchequer and leader of the House of Commons. In 1859, Lord Palmerston formed a new mixed government with Radicals included, and Gladstone again joined the government as chancellor of the exchequer, leaving the Conservatives to become part of the new Liberal Party.

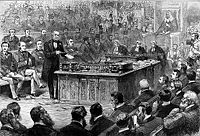

During consideration of his budget for 1860, it was generally assumed that Gladstone would use the budget's surplus of ÂŁ5 million to abolish the income tax, as in 1853 he had promised to do this before the decade was out. Instead, Gladstone proposed to increase it and use the additional revenue to abolish duties on paper, a controversial policy because the duties had traditionally inflated the costs of publishing and disseminating radical working-class ideas. Although Palmerston supported continuation of the duties, using them and income tax revenues to make armament purchases, a majority of his Cabinet supported Gladstone. The bill to abolish duties on paper narrowly passed Commons but was rejected by the House of Lords. As no money bill had been rejected by Lords for over two hundred years, a furor arose over this vote. The next year, Gladstone included the abolition of paper duties in a finance bill in order to force the Lords to accept it, and they did.

Significantly, Gladstone succeeded in steadily reducing the income tax over the course of his tenure as chancellor. In 1861 the tax was reduced to ninepence; in 1863 to sevenpence; in 1864 to fivepence; and in 1865 to fourpence.[1] Gladstone believed that government was extravagant and wasteful with taxpayers' money and so sought to let money "fructify in the pockets of the people" by keeping taxation levels down through "peace and retrenchment."

When Gladstone first joined Palmerston's government in 1859, he opposed further electoral reform, but he moved toward the left during Palmerston's last premiership, and by 1865 he was firmly in favor of enfranchising the working classes in towns. This latter policy created friction with Palmerston, who strongly opposed enfranchisement. At the beginning of each session, Gladstone would passionately urge the Cabinet to adopt new policies, while Palmerston would fixedly stare at a paper before him. At a lull in Gladstone's speech, Palmerston would smile, rap the table with his knuckles, and interject pointedly, "Now, my Lords and gentlemen, let us go to business".[2]

As chancellor, Gladstone made a controversial speech at Newcastle upon Tyne on October 7, 1862 in which he supported the independence of the Confederate States of America in the American Civil War, claiming that Jefferson Davis had a "made a nation." Great Britain was officially neutral at the time, and Gladstone later regretted the Newcastle speech. In May 1864, Gladstone said that he saw no reason in principle why all mentally-able men could not be enfranchised, but admitted that this would only come about once the working classes themselves showed more interest in the subject. Queen Victoria was not pleased with this statement, and an outraged Palmerston considered it seditious incitement to agitation.

Gladstone's support for electoral reform and disestablishment of the Anglican Church in Ireland had alienated him from his constituents in his Oxford University seat, and he lost it in the 1865 general election. A month later, however, he stood as a candidate in South Lancashire, where he was elected third MP (South Lancashire at this time elected three MPs). Palmerston campaigned for Gladstone in Oxford because he believed that his constituents would keep him "partially muzzled." A victorious Gladstone told his new constituency, "At last, my friends, I am come among you; and I am comeâto use an expression which has become very famous and is not likely to be forgottenâI am come 'unmuzzled.'"

In 1858 Gladstone took up the hobby of tree felling, mostly of oak trees, an exercise he continued with enthusiasm until he was 81 in 1891. Eventually, he became notorious for this activity, prompting Lord Randolph Churchill to snicker, "The forest laments in order that Mr. Gladstone may perspire." Less noticed at the time was his practice of replacing the trees he'd felled with newly-planted saplings. Possibly related to this hobby is the fact that Gladstone was a lifelong bibliophile.

First ministry, 1868â1874

Lord Russell retired in 1867 and Gladstone became a leader of the Liberal Party. In the next general election in 1868 he was defeated in Lancashire but was elected MP for Greenwich, it being quite common then for candidates to stand in two constituencies simultaneously. He became prime minister for the first time and remained in the office until 1874.

In the 1860s and 1870s, Gladstonian Liberalism was characterized by a number of policies intended to improve individual liberty and loosen political and economic restraints. First was the minimization of public expenditure on the premise that the economy and society were best helped by allowing people to spend as they saw fit. Secondly, his foreign policy aimed at promoting peace to help reduce expenditures and taxation and enhance trade. Thirdly, laws that prevented people from acting freely to improve themselves were reformed.

Gladstone's first premiership instituted reforms in the British Army, civil service, and local government to cut restrictions on individual advancement. He instituted abolition of the sale of commissions in the army as well as court reorganization. In foreign affairs his overriding aim was to promote peace and understanding, characterized by his settlement of the Alabama Claims in 1872 in favor of the Americans.

Gladstone transformed the Liberal Party during his first premiership (following expansion of the electorate in the wake of Disraeli's Reform Act of 1867). The 1867 Act gave the vote to every male adult householder living in a borough constituency. Male lodgers paying ÂŁ10 for unfurnished rooms also received the vote. This Act expanded the electorate by approximately 1.5 million men. It also changed the electoral map; constituencies and boroughs with less than 10,000 inhabitants lost one of their MPs. The 45 seats left available through the reorganization were distributed by the following procedures:

- giving fifteen to towns which had never had an MP

- giving one extra seat to some larger townsâLiverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds

- creating a seat for the University of London

- giving 25 seats to counties whose population had increased since 1832

The issue of disestablishment of the Church of Ireland was used by Gladstone to unite the Liberal Party for government in 1868. The Act was passed in 1869 and meant that Irish Roman Catholics did not need to pay their tithes to the Anglican Church of Ireland. He also instituted Cardwell's Army Reform that in 1869 made peacetime flogging illegal; the Irish Land Act; and the Forster's Education Act in 1870. In 1871 he instituted the University Test Act. In 1872, he secured passage of the Ballot Act for secret voting ballots. In 1873, his leadership led to the passage of laws restructuring the High Courts.

Out of office and the Midlothian Campaign

In 1874, the Liberals lost the election. In the wake of Benjamin Disraeli's victory, Gladstone retired temporarily from the leadership of the Liberal Party, although he retained his seat in the House. He considered leaving politics and entering the Anglican ministry.

A pamphlet published in 1876, Bulgarian Horrors and the Questions of the East, attacked the Disraeli government for its indifference to the violent repression of the Bulgarian rebellion in Ottoman Empire (Known as the Bulgarian April uprising). An often-quoted excerpt illustrates his formidable rhetorical powers:

<blockquuote>Let the Turks now carry away their abuses, in the only possible manner, namely, by carrying off themselves. Their Zaptiehs and their Mudirs, their Bimbashis and Yuzbachis, their Kaimakans and their Pashas, one and all, bag and baggage, shall, I hope, clear out from the province that they have desolated and profaned. This thorough riddance, this most blessed deliverance, is the only reparation we can make to those heaps and heaps of dead, the violated purity alike of matron and of maiden and of child; to the civilization which has been affronted and shamed; to the laws of God, or, if you like, of Allah; to the moral sense of mankind at large. There is not a criminal in a European jail, there is not a criminal in the South Sea Islands, whose indignation would not rise and over-boil at the recital of that which has been done, which has too late been examined, but which remains unavenged, which has left behind all the foul and all the fierce passions which produced it and which may again spring up in another murderous harvest from the soil soaked and reeking with blood and in the air tainted with every imaginable deed of crime and shame. That such things should be done once is a damning disgrace to the portion of our race which did them; that the door should be left open to their ever so barely possible repetition would spread that shame over the world.

During his rousing election campaign (the so-called Midlothian campaign) of 1879, he spoke against Disraeli's foreign policies during the ongoing The Second Anglo-Afghan War in Afghanistan. He saw the war as "great dishonour" and also criticized British conduct in the Zulu War.

Second ministry, 1880â1885

In 1880 the Liberals won again, and the new Liberal leader, Spencer Compton Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, retired in Gladstone's favor. Gladstone won his constituency election in Midlothian and also in Leeds, where he had also been adopted as a candidate. As he could lawfully only serve as MP for one constituency; Leeds was passed to his son Herbert Gladstone. One of his other sons, William Henry Gladstone, was also elected as an MP.

Queen Victoria asked Spencer Compton Cavendish, to form a ministry, but he persuaded her to send for Gladstone. Gladstone's second administrationâboth as prime minister and again as chancellor of the exchequer until 1882âlasted from June 1880 to June 1885. Gladstone had opposed himself to the "colonicolonial lobby" pushing for the scramble for Africa. He thus saw the end of the Second Anglo-Afghan War, First Boer War and the war against the Mahdi in Sudan.

However, he couldn't respect his electoral promise to disengage from Egypt. June 1882 saw a riot in the Egyptian city of Alexandria, with about three hundred people being killed as part of the Urabi Revolt. In Parliament an angry and retributive mood developed against Egypt, and the Cabinet approved the bombardment of Urabi's gun emplacements by Admiral Sir Beauchamp Seymour and the subsequent landing of British troops to restore order to the city. Gladstone defended this in the Commons by exclaiming that Egypt was "in a state of military violence, without any law whatsoever."[3]

In 1881 he established the Irish Coercion Act, which permitted the viceroy to detain people for as "long as was thought necessary." He also extended the franchise to agricultural laborers and others in the 1884 Reform Act, which gave the counties the same franchise as the boroughsâadult male householders and ÂŁ10 lodgersâand added about six million to the total number who could vote in parliamentary elections. Parliamentary reform continued with the Redistribution of Seats Act 1885.

Gladstone was becoming increasingly uneasy about the direction in which British politics was moving. In a letter to John Dalberg-Acton, 1st Baron Acton on 11 February 1885, Gladstone criticised Tory Democracy as "demagogism" that "put down pacific, law-respecting, economic elements that ennobled the old Conservatism" but "still, in secret, as obstinately attached as ever to the evil principle of class interests." He found contemporary Liberalism better, "but far from being good." Gladstone claimed that this Liberalism's "pet idea is what they call construction, that is to say, taking into the hands of the State the business of the individual man." Both Tory Democracy and this new Liberalism, Gladstone wrote, had done "much to estrange me, and had for many, many years".[4]

The fall of General Gordon in Khartoum, Sudan, in 1885 was a major blow to Gladstone's popularity. Many believed Gladstone had neglected military affairs and had not acted promptly enough to save the besieged Gordon. Critics inverted his acronym, "G.O.M." (for "Grand Old Man"), to "M.O.G." (for "Murderer of Gordon"). He resigned as prime minister in 1885 and declined Victoria's offer of an Earldom.

Third ministry, 1886

In 1886 Gladstone's party was allied with Irish Nationalists to defeat Lord Salisbury's government; Gladstone regained his position as PM and combined the office with that of Lord Privy Seal. During this administration he first introduced his Home Rule Bill for Ireland. The issue split the Liberal Party and the bill was thrown out on the second reading, ending his government after only a few months and inaugurating another headed by Lord Salisbury.

Fourth ministry, 1892â1894

In 1892 Gladstone was re-elected Prime Minister for the fourth and final time. In February 1893 he re-introduced a Home Rule Bill. It provided for the formation of a parliament for Ireland, or in modern terminology, a regional assembly of the type Northern Ireland gained from the Good Friday Agreement. The Home Rule Bill did not offer Ireland independence, but the Irish Parliamentary Party had not demanded independence in the first place. The Bill was passed by the Commons but rejected by the House of Lords on the grounds that it had gone too far. On March 1, 1894, in his last speech to the House of Commons, Gladstone asked his allies to override this most recent veto. He resigned two days later, although he retained his seat in the Commons until 1895. Years later, as Irish independence loomed, King George V exclaimed to a friend, "What fools we were not to pass Mr. Gladstone's bill when we had the chance!"

Gladstone's Christianity

Gladstone's faith informed his policies, his passion for justice and his hatred of oppression. From his Oxford days onwards he identified with the high church form of Anglicanism. He published several works on Horace and Homer including Studies on Homer (1858). He knew many of the most renowned literary figures of the day, a distinction he shared with his chief political opponent, Benjamin Disraeli. He enjoyed a reputation for his scholarship, although his critics suggested that he would rather read widely than think deep thoughts.

His faith combined belief in traditional doctrines of the Church of England with a Homeric confidence in human ability. He always observed Sunday worship and often attended church daily. In his writing, he tried to reconcile Christianity with the modern world. He saw upholding and teaching religious truth as a duty of government. He supported the alliance between church and state; while the church cared for the soul of the nation, the state cared for people and property. Governmentâs role, indeed, was paternal towards its citizens.[5]

According to Gladstone, Anglicanism had got the relationship between church and state right; each was equal but exercised their authority in different spheres. He was critical of low-church Anglicanism and of some other denominations for either opposing the State or for being too servile towards the state. On moral issues, however, the church could rightly check the power of the state.

Gladstone was famous for his wide reading, which ranged from the classics to such contemporary authors as Charles Dickens and the Brontës. From 1874 onwards, he also read a great deal of theology and religious history. The sermons and homilies he read may have influenced his oratory, which has been described as an art form. He denounced the 1874 bull on papal infallibility. He was upset when several life-long friend became Catholic, as did his own sister. His main objection was that Catholicism was illiberal and too superstitious. He was a life-long friend and admirer of Alfred Lord Tennyson, once commenting that the poet's life had been lived on a higher plane than his own.

Final years

In 1895 at the age of 85, Gladstone bequeathed 40,000 Pounds sterling and much of his library to found St. Deiniol's Library, the only residential library in Britain. Despite his advanced age, he himself lugged most of his 23,000 books a quarter mile to their new home, using his wheelbarrow.

In 1896 in his last noteworthy speech, he denounced Armenian massacres by Ottomans in a talk delivered at Liverpool.

Gladstone died at Hawarden Castle in 1898 at the age of 88 from metastatic cancer that had started behind his cheekbone. His coffin was transported on the London Underground before he was buried in Westminster Abbey. His wife, Catherine Glynne Gladstone, was later laid to rest with him (see image at right).

A statue of Gladstone, erected in 1905, is situated at Aldwych, London, nearby to the Royal Courts of Justice.[6] There is also a statue of him in Glasgow's George Square and in other towns around the country.

Liverpool's Crest Hotel was renamed The Gladstone Hotel in his honor in the early 1990s.

Near to Hawarden in the town of Mancot, there is a small hospital named after Catherine Gladstone. A statue of her husband also stands near the high school in Hawarden.

Gladstone's Governments

- First Gladstone Ministry (December 1868âFebruary 1874)

- Second Gladstone Ministry (April 1880âJune 1885)

- Third Gladstone Ministry (FebruaryâAugust 1886)

- Fourth Gladstone Ministry (August 1892âFebruary 1894)

Footnotes

- â L. C. B. Seaman, Victorian England: Aspects of English and Imperial History, 1837-1901 (London: Routledge, 1973), pp. 183-184.

- â Jasper Ridley, Lord Palmerston (London: Constable, 1970), p. 563.

- â Lawrence James, The Rise and Fall of the British Empire (New York: St. Martinâs Press, 1999, ISBN 0312264291), p. 272.

- â John Morley, The Life of William Ewart Gladstone: Volume III, pp. 172-3. NY: Greenowood Press, 1968, original 1903

- â William Gladstone, âThe State in its Relations with the Church,â in Critical and Historical Essays, Volume 2, edited by Thomas B. Macaulay. Available online from World Wide School. Retrieved August 10, 2007.

- â A&A: W. E. Gladstone Monument, Art & Architecture. Retrieved August 10, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bebbington, David. The Mind of Gladstone: Religion, Homer and Politics. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 0199267650

- Bebbington, David. William Ewart Gladstone: Faith and Politics in Victorian Britain. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1993. ISBN 0802801528

- Burdett, Osbert. W. E. Gladstone. London: Constable & Co., 1928.

- Gunsaulus, Frank W. William Ewart Gladstone: A Biographical Study. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2005. ISBN 978-1417902484

- Jenkins, Roy. Gladstone. New York: Random House, 1995. ISBN 0679451447

- Magnus, Philip. Gladstone: A Biography. London: J. Murray, 1954.

- Matthew, H. C. Gladstone: 1809-98. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 0192821229

Books by Gladstone

- Gladstone, William E. Juventus Mundi: The Gods and Men of the Heroic Age. London: Macmillan and Co., 1869.

- Gladstone, William E. The Odes of Horace. New York: C. Scribnerâs Sons, 1901.

- Gladstone, William E. Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1858.

- Gladstone, William E. Correspondence on Church and Religion. London: J. Murray, 1910.

- Gladstone, William E. Protestantism and Catholicism in Their Bearing upon the Liberty and Prosperity of Nations. Toronto: Belford Bros., 1876.

External links

All links retrieved May 8, 2023.

- William Ewart Gladstone by M. B. Synge â The Baldwin Project

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.