United States Korean expedition

| United States Korean expedition | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

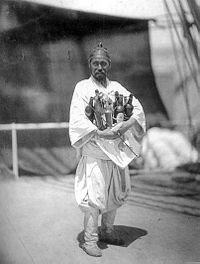

Koreans who died in Gwangseong Garrison. Albumen silver print by Felice Beato, 1871. | ||||||||

| Korean name | ||||||||

|

The United States expedition to Korea in 1871, which came to be known in Korea as Sinmiyangyo (Korean: 신미양요 ,Western Disturbance of the Year Sinmi) started out as a diplomatic mission. During the previous decade, while the United States was consumed by Civil War, England, France and other European nations had expanded their foreign trade relations with Asian countries, particularly China and Japan. Emerging from the Civil War, the United States wanted to catch up, and sought to make a trade agreement with the Joseon Kingdom, as Korea was known at that time. Unfortunately the culture gap between the hermit kingdom Korea and the United States proved insurmountable, and their mutual misunderstanding led to a military conflict which ultimately yielded no useful results for either side.

Background

Korea and China

For several centuries leading up to the nineteenth, Korea had maintained a relationship of tribute with China. In exchange for annual payments of tribute by Korea, China provided a buffer of protection, while still considering Korea an independent nation, and commerce was conducted between the two countries. As a result of this long-standing and effective relationship with China, Korea, a peninsular nation geographically separated from the rest of the world, had not faced the necessity of conducting relations with any other outside countries. As Europe and the United States began to travel to Asia in search of trade relations and colonies, western ships began to make occasional visits to Korea. Korea was not eager to engage in communications with them, feeling that they had no need of relations with any outside peoples, other than China. China did its best to try to explain Korea's position to outside countries and vice versa, but only to the point that it did not threaten or interfere with the China – Korea relationship.

The General Sherman Incident

In 1866, a US merchant ship, the USS General Sherman, landed in Korea seeking trade opportunities. The ship was not welcomed; on the contrary, the crew was all killed or captured, and the General Sherman was burned. The USS Wachusett (1867) and the USS Shenandoah (1868) traveled to Korea to confirm the fate of the General Sherman and try to rescue any survivors, but were not afforded any official meetings or information. From local residents near the Taedong River, they heard that the General Sherman had been destroyed by fire, and were told conflicting stories about survivors.

Since single ships had been unable to obtain any clear information, the United States Department of State decided to send an official delegation of ships to Korea, following the recommendation of the American Consul in Shanghai, General George Seward. In addition to seeking official information about the General Sherman, the delegation would negotiate a trade treaty similar to the treaties Korea had with China and Japan. The State Department stipulated that no military force should used in securing the treaty. About the same time, a US businessman in Shanghai, China, Frederick Jenkins, reported to Seward that Korea had sent a delegation to Shanghai to inquire about the most effective way to respond to the US regarding the General Sherman incident; whether it might be appropriate to send a delegation to Washington to report. It is not known for certain what conclusions were reached, but no such delegation ever arrived in Washington.

Attempts at liaison through China

As the American expedition, based in Shanghai, prepared for the trip to Korea, the US's main representative in China, Minister Frederic Low, prepared a diplomatic message to send to Korea through China's Zongli Yamen (foreign office). The Chinese were reluctant to get involved, eager to maintain their neutrality and avoid jeopardizing their relations with Korea and the US. However, when it became clear that the Americans planned to travel to Korea whether or not China assisted them or approved of the mission, China finally agreed to forward Minister Low official letter to Korea.

On receiving the letter, the Korean government faced a dilemma: they wanted to firmly convey to the Americans that they were not welcome and should not come; on the other hand, any letter of response to the US would in and of itself be considered as the beginning of a relationship of communication, something Korea also did not want. They drafted a response designed to satisfy both of these stances. They wrote a response asking China to tell the US that they could not meet with the US delegation and that there was nothing to discuss about the "General Sherman," since the fate of the 'General Sherman' was brought upon it by the hostile actions of its crew. Unfortunately, the reply reached China too late; the American squadron had already set sail for Korea.

Initial Contact

The expeditionary force that set out for Korea from China included over 1,200 sailors and Marines and five ships: USS Colorado, USS Alaska, USS Palos, USS Monocacy, and USS Benicia, as well as a number of smaller support vessels. On board the Colorado, Rear Admiral John Rodgers' flag ship, was Frederick F. Low, the United States Ambassador to China. Accompanying the American contingent was photographer Felice Beato, known for his photographic work in Asia, and one of the earliest war photographers. The Korean forces, known as "Tiger Hunters," were led by general Eo Je-yeon (Korean: 어재연 Hanja: 魚在淵).

The Americans safely made contact with the Korean inhabitants, described as people wearing white clothes, and, when they inquired them about the USS General Sherman incident, the Koreans were initially reluctant to discuss the topic, because they feared paying any recompense.

Request Permission to Explore the Coast

When an official delegation from King Gojong visited the American flagship U.S.S. Colorado on May 31, the Americans, speaking to the delegation through their Chinese-speaking interpreter, told the Koreans that they planned to explore and survey the coastline in the upcoming days. They also presented the Korean delegation with some gifts. The Americans assumed that the Koreans' failure to voice any objections to the surveying trip indicated tacit approval. This was far from the truth. The Korean policy at the time allowed no safe passage for foreign ships into the Han River, for the river led directly to the Korean capital Hanyang (modern Seoul). Also, no vessel was permitted to journey past the bend in the river at Sandolmok, near Ganghwa city, without express written permission from the local authorities.

Permission Denied

On June 1, the Alaska and the Monocacy, which had drafts shallow enough to maneuver in the shallow waters of the Ganghwa Straights began their surveying trip, manned by a crew of about 650 men, including about 100 marines. They proceeded up the river with what they thought was tacit permission from the Koreans. The Koreans, on the other hand, considered the waters closed to foreigners unless specific permission had been given to enter the waters, and as soon as the US ships reached Sandolmok, the Korean soldiers in the fortresses on the riverbank fired their cannons at the US ships. The Korean cannons were outdated, poorly positioned and in disrepair such that the Koreans could not aim well, and most of the shots sailed over the US ships. Since the Americans did not understand why the Koreans had opened fire, the Americans planned a punitive assault.

The armed conflict

On June 10, 1871, the Americans attacked Choji Garrison on Ganghwa and met nearly no opposition; they camped nearby overnight. The next morning, they finished destroying the fort and its guns. This same fort had previously been destroyed and rebuilt following the French incursions of 1866, and was later shelled again by the Japanese in 1876 in the events leading to the Treaty of Ganghwa. The Korean forces banded together as guerrilla units but, armed with only matchlocks, and being kept in check by American 12 pound howitzers, they could not get within effective firing range. The US troops moved on toward the next objective, Deokjin Garrison (Fort Monocacy).

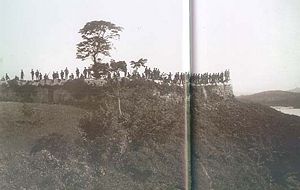

The Korean forces had abandoned Deokjin and chose to mass together further north. The Marines quickly dismantled this fortress in the same fashion as they did for the Choji garrison. American forces continued to Gwangseong Garrison (the Citadel). By that time, Korean forces had regrouped there en masse. Along the way, some Korean units tried to flank the US forces; they were checked, again, by the strategic placement of artillery on two hills near the Citadel.

Artillery from both ground and USS Monocacy and the other 4 ships offshore pounded the Citadel and the hill directly west of it, in preparation for an assault by US forces. The US troops of nine companies of sailors and one company of Marines, grouped on the facing hill, keeping cover and returning fire.

When a signal was given, the bombardments stopped and the Americans made a charge against the Citadel, with Lt. Hugh McKee in the lead. The slow reload time of the Korean matchlock rifles allowed the Americans, who were armed with superior bolt action rifles, to overwhelm the walls; the Koreans even ended up throwing rocks at the attackers. Lt. McKee, the first to make it into the Citadel, was shot in the groin and speared by the side. After him came Commander Schley, avenging his comrade.

The fighting lasted 15 minutes. Those who saw defeat as inevitable, including General Eo, took their lives by the river. In the end, about 350 Koreans and three Americans died (Lt. McKee, Ordinary Seaman Seth Allen, and USMC Pvt. Dennis Hannahan), nine Americans were wounded, and 20 wounded Koreans were captured. The Korean deputy commander was among the wounded who were captured. The US hoped to use the captives as a bargaining chip to meet with Korean officials, but the Koreans would not negotiate.

Who are the civilized, Who are not?

In Hanyang, scholar Kim Pyeong-hak advised the young King Gojong that the United States consisted merely of a collection of settlements, adding that it was not necessary to take them too seriously. Back in the US, on the other hand, a New York newspaper described the incident as America's Little War with the Heathens. Neither the Koreans nor the Americans came even close to understanding the strengths of the other's culture. One of the oldest cultures in the world, Korea had a history of more than 4,000 years. The United States, it is true, was a very young civilization, but it was not a nation formed by peoples recently banded together from a life of hunting and gathering. The United States was a new territory settled by immigrants from some of the strongest cultures in the contemporary world, and possessed strengths and an international standing far beyond its years as a nation.

Aftermath

The Americans met stiff resistance a short time later when they made second attempt to continue up the Han River toward Hanyang. The US diplomatically was not able achieve its objectives, as the Koreans refused to open up the country to them (and the US forces did not have the authority or strength to press further). Concluding that staying longer would not produce any superior results, the US fleet departed for China on July 3.

For their part, the Koreans were convinced that it was their military superiority that drove the Americans away. It did not seem to matter that the US had suffered only a handful of casualties and their own forces had lost several hundred. The regent Daewongun was emboldened to strengthen his policy of isolation and issue a national proclamation against appeasing the barbarians.

Foreign trade treaties

However, despite Daewongun's efforts to maintain isolation throughout the rest of his administration, and King Gojong's policies when his direct reign starting in 1873, continuing with the same emphasis on isolation, it was not possible for Korea to stay separated from the world forever, and in 1876, Korea established its first modern treaty, a trade treaty with Japan after Japanese ships approached Ganghwado and threatened to fire on Seoul. This treaty, the Treaty of Ganghwa, was the first in a series of unequal treaties that Korea signed near the end of the nineteenth century, and, at least in the eyes of Japan and Korea, signaled the end of Korea's tributary relationship with China.

A few years later, in 1882, after some Japanese citizens were killed during local unrest in Korea, Japan demanded that Korea signed a new, stronger treaty, which had several provisions protecting Japanese citizens in Korea. This Treaty of Jemulpo is named for the place where it was signed, now part of the city of Incheon. There were also treaties with European countries and the US followed the same year. Negotiated and approved in April and May 1882 between the United States, working with Chinese negotiators and Korea, the Treaty of Peace, Amity Commerce and Navigation, sometimes also referred to as the Jemulpo Treaty, contained 14 articles, which established mutual friendship and defense in case of attack, the ability of Koreans to emigrate to the US, most favored nation trade status, extraterritorial rights for American citizens in Korea, and non-interference with Christian missionaries proselytizing in Korea.

The treaty remained in effect until the annexation of Korea in 1910 by Japan, which maintained control over Korea until the end of World War II. The next US military presence in Korea took place at the end of WWII, in 1945; and the next military conflict in Korea, also involving the US, was the 1950-1953 Korean War.

See also

- History of Korea

- Military history of Korea

- Joseon Dynasty

- French Campaign against Korea, 1866

- Ganghwa Island incident

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Axelrod, Alan. 2007. Political history of America's wars. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. ISBN 9781568029566

- Nahm, Andrew C. 1988. A history of the Korean People: Korea; tradition & transformation. Korea: Hollym. OCLC: 55238016

- Yi, Ki-baek. 1984. A new history of Korea. Cambridge, Mass: Published for the Harvard-Yenching Institute by Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674615755

External links

All links retrieved May 3, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.