Treaty of Utrecht

The Treaty of Utrecht that established the Peace of Utrecht, rather than a single document, comprised a series of individual peace treaties signed in the Dutch city of Utrecht in March and April 1713. Concluded between various European states, it helped end the War of the Spanish Succession (1702-1713). The treaty enforced the Partition Treaties of (1697) and (1700) which stated that the Spanish and French Crowns should never be united. This was part of British foreign policy to make peace in Europe by establishing a balance of power and preventing France in particular from uniting and dominating the continent. The treaty made Philip V, grandson of Louis XIV, King of Spain. The treaty stated that Britain should have Gibraltar, Minorca, Hudson Bay, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. Britain was awarded the Assientoâthe sole right to import black slaves into America for 30 years. Under the treaty France also had to acknowledge the Protestant Succession in England and Austria acquired Milan, Naples, and the Spanish Netherlands.

The treaties were concluded between the representatives of Louis XIV of France and Philip V of Spain on the one hand, and representatives of Queen Anne of Great Britain, the Duke of Savoy, and the Dutch Republic on the other.

The Treaty of Utrecht brought a period of peace in what is sometimes called the Second Hundred Years War (1689-1815) between France and Britain. This rivalry had international dimensions in the scramble for overseas territories, wealth and influence. The treaty significantly contributed to the Anglicization of North America. The Triple Alliance (1717) was formed with France and Holland to uphold the Treaty of Utrecht. In 1718 Austria joined and it was expanded to the Quadruple Alliance against Spain to maintain the peace of Europe.

The Negotiations

France and Great Britain had come to terms in October 1711, when the preliminaries of peace had been signed in London. This initial agreement was based on a tacit acceptance of the partition of Spain's European possessions. Following this, a congress opened at Utrecht on January 29, 1712. The British representative was John Robinson (the Bishop of Bristol). Reluctantly the Dutch United Provinces accepted the preliminaries and sent representatives, but the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles VI, refused to do so until he was assured that these preliminaries were not binding. This assurance was given, and so in February the Imperial representatives made their appearance. As Philip was not yet recognized as its king, Spain did not at first send plenipotentiaries, but the Duke of Savoy sent one, and Portugal was also represented.

One of the first questions discussed was the nature of the guarantees to be given by France and Spain that their crowns would be kept separate, and matters did not make much progress until after July 10, 1712, when Philip signed a renunciation. With Great Britain and France having agreed a truce, the pace of negotiation now quickened, and the main treaties were finally signed on April 11, 1713.

Principal provisions

By the treaties' provisions, Louis XIV's grandson Philip, Duke of Anjou was recognized as King of Spain (as Philip V), thus confirming the succession as stipulated in the will of the late King Charles II. However, Philip was compelled to renounce for himself and his descendants any right to the French throne, despite some doubts as to the lawfulness of such an act. In similar fashion various French princelings, including most notably the Duke of Berry (Louis XIV's youngest grandson) and the Duke of Orléans (Louis's nephew), renounced for themselves and their descendants any claim to the Spanish throne.

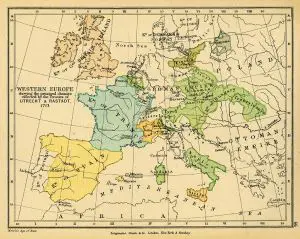

Spain's European empire was also divided: Savoy received Sicily and parts of the Duchy of Milan, while Charles VI (the Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria), received the Spanish Netherlands, the Kingdom of Naples, Sardinia, and the bulk of the Duchy of Milan. In addition, Spain ceded Gibraltar and Minorca to Great Britain and agreed to give to the British the Asiento, a valuable monopoly slave-trading contract.

In North America, France ceded to Great Britain its claims to the Hudson Bay Company territories in Rupert's Land, Newfoundland, and Acadia. The formerly partitioned island of Saint Kitts was also ceded in its entirety to Britain. France retained its other pre-war North American possessions, including Ãle-Saint-Jean (now Prince Edward Island) as well as Ãle Royale (now Cape Breton Island), on which it erected the Fortress of Louisbourg.

A series of commercial treaties were also signed.

After the signing of the Utrecht treaties, the French continued to be at war with Emperor Charles VI and with the Holy Roman Empire itself until 1714, when hostilities were ended with the Treaty of Rastatt and the Treaty of Baden. Spain and Portugal remained formally at war with each other until the Treaty of Madrid in 1715, while the Empire and the now-Bourbon Spain did not conclude peace until 1720.

Responses to the treaties

The treaty's territorial provisions did not go as far as the Whigs in Britain would have liked, considering that the French had made overtures for peace in 1706 and again in 1709. The Whigs considered themselves the heirs of the staunch anti-French policies of William III and the Duke of Marlborough. Indeed, later in the century the Whig John Wilkes contemptuously described it as like "[the] Peace of God, for it passeth all understanding." However, in the Parliament of 1710 the Tories had gained control of the House of Commons, and they wished for an end to Britain's participation in a European war. Jonathan Swift complained fiercely about the cost of the war and the debts that had been incurred. People were also weary of war and the taxation to finance it. Queen Anne and her advisers had also come to the same position which led to the Whig administration being dismissed by the Queen and a Tory one formed under Robert Harley (created Earl of Oxford and Mortimer on May 23, 1711) and Viscount Bolingbroke.

Harley and the Bolingbroke proved more flexible at the bargaining table and were accused by the Whigs of being "pro-French." They persuaded the Queen to create twelve new "Tory peers."[1][2] to ensure ratification of the treaty in the House of Lords.

Although the fate of the Spanish Netherlands in particular was of interest to the United Provinces, Dutch influence on the outcome of the negotiations was fairly insignificant, even though the talks were held on their territory. This led to the creation of a Dutch proverbial saying: "De vous, chez vous, sans vous," literally meaning "concerning you, in your house, but without you."

Balance of power

The European concept of the balance of power, first mentioned in 1701 by Charles Davenant in Essays on the Balance of Power, became a common topic of debate during the war and the conferences that led to the signing of the treaties. Boosted by the issue of Daniel Defoe's A Review of the Affairs of France in 1709, a periodical which supported the Harley ministry, the concept was a key factor in British negotiations, and was reflected in the final treaties. This theme would continue to be a significant factor in European politics until the time of the French Revolution (and was to resurface in the nineteenth century and also during the Cold War in the second half of the twentieth century).

Notes

- â The twelve peers consisted of two who were summoned in their father's baronies, Lords Compton (Northampton) and Bruce (Ailesbury), and ten recruits, namely Lords Hay (Kinnoull), Mountjoy, Burton (Paget), Mansell, Middleton, Trevor, Lansdowne, Masham, Foley, and Bathurst.

- â David Backhouse, Tory Tergiversation In The House Of Lords, 1714-1760, University of London, 2007. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Backhouse, David. Tory Tergiversation In The House Of Lords, 1714-1760. University of London, 2007. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- Frey, Linda, and Marsha Frey. A Question of Empire Leopold I and the War of Spanish Succession, 1701-1705. East European monographs, no. 146. Boulder: East European Monographs, 1983. ISBN 9780880330381

- Müllenbrock, Heinz-Joachim. The Culture of Contention A Rhetorical Analysis of the Public Controversy About the Ending of the War of the Spanish Succession, 1710-1713. München: Fink, 1997. ISBN 9783770532087

- Stanhope, Philip Henry Stanhope. History of England from the Peace of Utrecht to the Peace of Versailles, 1713-1783. New York: AMS Press, 1975. ISBN 9780404062408

External links

All links retrieved May 2, 2023.

- "The Treaties of Utrecht (1713)" â Brief discussion and extracts of the various treaties on François Velde's Heraldica website, with particular focus on the renunciations and their later reconfirmations.

- Article X of the treaty between Great Britain and Spain â Concerning the cession of Gibraltar (text in English, Spanish, and the original Latin).

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.