Mount Vernon

Mount Vernon, Virginia, was the plantation home of the first president of the United States, George Washington. Built of wood in a neoclassical Georgian architectural style, the estate is located near Mount Vernon, Virginia in Fairfax County, on the banks of the Potomac River.

Washington and his family referred to their farm as "Mansion House Farm." A skilled surveyor and horticulturist, Washington created a fine setting for a country gentleman out of five hundred acres. His carefully designed grounds had lush rolling meadows, winding walkways, a pleasure garden, a kitchen garden, groves of trees, and very deep woods. Of special note was a large park located between the mansion and the Potomac River.

With its varied tradesâcarpentry, masonry, blacksmithing, planting, even whiskey distillationâMount Vernon was, as mush as possible, a self-sufficient community. Indeed, Washington instructed that nothing should be purchased that could be made on the farm. To meet these needs, there was a large slave population at the Mansion House Farm, consisting of 316 people at the time of Washingtonâs death. Thus, as was the manner at the time, service lanes use by slaves were designed not to impinge upon the places reserved for the use of Washington, his family, and their many guests.

From the Potomac River on the east to the estate's west-gate entrance ran the pleasure grounds with its wide-open vistas where Washington entertained. Along the north-south line were the outbuildings, where much of the varied work was done by the slaves. Washington had serious misgivings about slavery at the time of the Revolutionary War and, upon his death, had all of his slaves freed at Mount Vernon, a number of whom remained on the estate through the 1830s, at the behest of Washington.

Mount Vernon is one of the most visited colonial sites in America and remains a valuable historical testimony to America's first president and the lifestyle of his times, both good and bad.

Origins

The early history of the land on which Mount Vernon is situated is separate from that of the home, which was not erected until 1741-1742 and occupied for the first time in 1743. In 1674 John Washington and Nicholas Spencer came into possession of the land from which Mount Vernon plantation would be carved. When Washington died in 1677, his son Lawrence, George Washington's grandfather, inherited his father's stake in the property. In 1690, he agreed to formally divide the estimated five thousand-acre estate with the heirs of Nicholas Spencer. The Spencers took the southern half bordering Dogue Creek (originally called "Epsewasson" in the September 1674 land grant from Lord Culpeper, after the former name of the creek) leaving the Washingtons the portion along Little Hunting Creek.

Upon Lawrence Washington's death in 1678, he left the property to his daughter, Mildred. In 1726, at the urging of her brother Augustine (George Washington's father), Mildred sold him the Potomac River estate. In 1735, Augustine Washington moved his young second family, including the toddler George, to the estate, settling into a "Quarter" alongside Little Hunting Creek. In 1738, Augustine recalled his eldest son Lawrence (George's half-brother) home from The Appleby School in England, and set him up on the family's Little Hunting Creek tobacco plantation, thereby allowing Augustine to move his family back to Fredericksburg at the end of 1738.

In 1739, Lawrence, having reached his 'majority' (age 21) began buying up parcels of land from the adjoining Spencer tract, beginning with the land around the Grist Mill on Dogue Creek. In the summer of 1740, Lawrence received a coveted officer's commission in the Regular British Army, and made preparations to go off to war in the Caribbean with the newly formed American Regiment. Part of his preparations included ensuring his father had legal control over the tracts Lawrence had purchased from Spencer. While he was away at war (1739-1743), Lawrence wrote to his father from Jamaica in May 1741, that, should he survive the war, he intended to make his home in the town of Fredericksburg, building a townhouse on one of the three lots he owned there.

Land-sale dispute

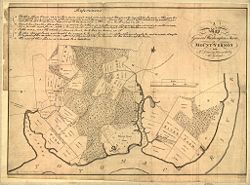

At this same time, the Spencer family was in a legal dispute over additional land sales to Lawrence's neighbors. To adjudicate the boundary-line dispute, a general court for Prince William County ordered a new survey of the entire five thousand-acre, Washington-Spencer land grant. The surviving map of that 1741 survey, a plat, by county surveyor Robert Brooke, revealed the estate had been grossly mismeasured in April 1669, and it contained only about 4,200 acres, not the 5,000 acres conveyed in the 1674 land grant.

The mismeasurement can be attributed to the fact that the property was bounded on three sides by water, and that neither the river nor the two creeks ran straight. Pursuant to the Culpeper land grant, the original 1669 surveyor was charged with estimating an area of five thousand acres, and then blazing a straight-line "back" boundary along a tree line between the winding courses of Dogue Run and Little Hunting Creek. More importantly, this surviving May 1741 property survey by Brooke reveals that the location of the present-day mansion house was then vacant, with the Washingtons depicted as having their quarter alongside Little Hunting Creek.

Home is named

Upon receiving the news of his son's intention to live in Fredericksburg, Augustine Washington appears to have undertaken to erect a modest farm house on the vacant bluff overlooking the Potomac River (where the mansion house now sits) in 1741-1742. It is estimated Lawrence received the news of his father's plans in late 1741, while at Jamaica, and that he may have written back requesting his father to call the new home "Mount Vernon" in honor of Lawrence's commanding officer, Vice Admiral Edward Vernon, then regarded as the greatest military hero of the age in England.

In early August 1742, the place name "Mount Vernon" first appears in a surviving letter, penned by Lawrence's Potomac River neighbor, William Fairfax, of Belvoir. Lawrence Washington returned from the war in late 1742, burying his father in April 1743, married into the Fairfax family and took up residence at his "Mount Vernon" in July 1743. By the late 1740s Lawrence undertook an expansion of the home their father Augustine had built for him.

George Washington's occupancy

Upon Lawrence's untimely death in July 1752, George Washington, age 20, was already living at Mount Vernon and probably managing the plantation. But it was not until 1754 when he actually leased the property from Lawrence's widow, Anne Fairfax, who promptly remarried into the Lee family and moved out. Upon the death of Anne and Lawrence's only surviving child in 1754, George, as executor of his brother's estate, arranged to lease Mount Vernon that December from Fairfax.

In 1757, Washington began the first of two major additions and improvements to the home. The second expansion was begun shortly before the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. On those occasions he entirely rebuilt the main house atop the original foundations, doubling its size each time. The great majority of the work was performed by slaves and artisans. It is important to note that while he twice rebuilt the home, George never changed its patriotic British name.

Upon Anne Fairfax Washington Lee's death in 1761, Washington legally inherited the Mount Vernon estate, where he labored to become a prominent agriculturist. From 1759 until the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, Washington operated the estate as five separate farms. He took a scientific approach to farming and kept extensive and meticulous records of both labor and results. One of his most successful ventures was the establishment of a distillery; he became one of the new nation's largest distillers of whiskey.

Following his service in the war, Washington returned to Mount Vernon and in 1785-1786 spent a great deal of effort in improving the landscaping of the estate. It is estimated that during his two terms as president of the United States (1789-1797) Washington spent 434 days in residence at Mount Vernon. After his presidency, he tended to repairs to the buildings, socializing, and further gardening. The remains of George and his wife, Martha Washington, as well as other family members, are entombed on the grounds.

Dimension of main house

In its prime, Mount Vernon was an eight thousand-acre plantation divided into five farms. Each farm was a complete unit, with its own overseers, slave work force, livestock, equipment, and buildings. The centerpiece of the plantation was the two and a half story, Georgian frame house facing the Potomac River, the Washington's long-time home.

The exterior dimensions of the mansion are 94 feet by 33 feet. With the piazza, the measurements become 94 feet by 47 feet, six inches. Excluding the basement and piazza, there is some seven thousand square feet of livable floor space. The basement adds about three thousand square feet, and the piazza another 1,400 square feet of usable area to the main house.

From the first floor to the ridge of the roof, the height of the mansion is 33 feet, six inches. Another 25 feet is added on to the buildingâs height from the ridge of the roof to the top of the weathervane. The mansionâs colonnades were placed in a quarter circle, measuring 12 feet by 30 feet, and covering 274.85 square feet.

Slavery at Mount Vernon

At Mount Vernon, slaves lived and worked on the five farms which made up Washingtonâs plantation and at the grist mill, located three miles from the mansion. Many slaves were field hands with much of this labor done by women, while others were skilled in trades such as carpentry, masonry, and blacksmithing. House slaves included cooks, butlers and personal valets, and maids.

The buildings devoted to specialized work performed by the slaves at Mount Vernon were as varied as the farm's everyday needs: stable, mule shed and paddock; coach house; wash house and laundry yard; smokehouse; storehouse and clerk's quarters; kitchen; servants' hall; salthouse; overseer's quarters and spinning room; the greenhouse complex, with slave quarters; stove room; and shoemaker's shop.

In 1743, at the age of 11, Washington inherited ten slaves. Before moving to Mount Vernon on a permanent basis in 1754, he inherited eight more slaves, purchasing a like number soon after. When Washington married Martha Custis in 1759, she brought 11 slaves to Mount Vernon. Between the years 1759 to 1772, Washington purchased at least 42 additional slaves. Yet during the years 1775 to 1787, during the Revolution, he resolved never to buy or sell another slave. His slave population continued to grow, since he refused to separate families. In 1786, the earliest completed census of Mount Vernon slaves lists 216 men, women, and children, with 105 of them belonging to George Washington and 111 belonging to the estate of Marthaâs first husband, Daniel Parke Custis.

George Washington wrote to Lawrence Lewis in 1797: âI wish my soul that the legislature of this State could see a policy of gradual abolition of slavery.â In his will, Washington freed his slaves and left detailed instructions for their care and support. In July 1799, Washington drafted a second inventory in his will, in preparation of freeing his slaves (Virginia law prevented Washington from emancipating the slaves belonging to the Custis estate). Listed were 316 slaves, with 123 belonging to Washington.

When Washington died in December 1799, 316 slaves were living at Mount Vernon, of whom approximately 42 percent were too young or too old to work, but were provided for by the estate. In January 1801, Washingtonâs 123 slaves were freed. He left detailed instructions in his will for the care and support of the newly freed people, and records indicate that some lived on at Mount Vernon as pensioners until the 1830s.

Located 50 yards southwest of George Washingtonâs tomb is a cemetery for slaves and free blacks who worked for the Washington family. The graves are unmarked, and identities and numbers of those buried are largely unknown. William Lee, George Washingtonâs personal servant during the Revolutionary War, is buried there. He was freed in 1801 and died in 1828.

Preservation of the estate

After Washington's death in 1799, plantation ownership passed through a series of descendants who lacked either the will or the means to maintain the property. After trying unsuccessfully for five years to restore the estate, John Augustine Washington offered it for sale in 1848. The Virginia and United States governments declined to buy the home and estate.

| I have no objection to any sober or orderly person's gratifying their curiosity in viewing the buildings, Gardens, &ca. about Mount Vernon. âGeorge Washington, letter to William Pearce (November 23, 1794) |

In 1860, the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association of the Union, under the leadership of Ann Pamela Cunningham, acquired the mansion and a portion of the land for $200,000, rescuing it from a state of disrepair and neglect. The estate served as neutral ground for both sides during the American Civil War, although fighting raged across the nearby countryside. Mount Vernon was designated a National Historic Landmark on December 19, 1960, and later administratively listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The mansion has been restored by the Association (without accepting any state or Federal funds), complete with period furniture and fixings, and today serves as a popular tourist attraction. The estate is also well known for its exceptional landscaping and ancillary buildings.

Archaeological discoveries

There have been several architectural digs at Mount Vernon, with special significance given to the portersâ lodges measuring 12 by 14 feet that were discovered. Most view them as subsequent additions to the estate constructed by Washingtonâs nephew, Bushrod Washington, who owned the property from 1802 until his death in 1829. Rather than the traditional brick buildings, the lodges were built of pise, or rammed earth. Pise buildings, characterized by clay walls, are occasionally tempered with sand. Other pise structures at Mount Vernon include a barn, greenhouse, icehouse, and cow food boiler, the foundations of which are made of sandstone (possibly from 1812), and experimentations for pise slave quarters were also unearthed.

As to the dating of the lodges themselves, the evidence, as scarce as it may be, suggests that the sandstone foundations are the originals built in 1812, and do not date back to the time of George Washington. Further, soils found outside of the south lodge have nineteenth-century deposits that could provide information about the people who resided in the dwellings and how life at the west gate changed over the years.

Other educational attractions

On March 30, 2007, Washingtonâs Mount Vernon estate officially opened a reconstruction of Washingtonâs distillery. This fully functional replica received special legislation from the Virginia General Assembly to produce up to five thousand gallons of whiskey annually, for sale only at the Mount Vernon gift shop. The construction of this operational distillery cost $2.1 million and is located on the exact site as Washington's original distillery, a short distance from his mansion on the Potomac River. Funded by the Distilled Spirits Council, the distillery is designed to serve as a gateway to the American Whiskey Trail.

In October 2006, following a $110-million, fundraising campaign, two new buildings were opened as venues for much additional background on George Washington and the American Revolution. The Ford Orientation Center introduces visitors to George Washington and Mount Vernon with displays and a film. The Donald W. Reynolds Museum and Education Center houses many artifacts related to Washington along with multimedia displays and further films using modern entertainment technology.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dalzell, Robert F. and Lee Baldwin Dalzell. George Washington's Mount Vernon: At Home in Revolutionary America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0195136289

- Garrett, Wendell. Mount Vernon. Monacelli, 1998. ISBN 978-1580930109

- Griswold, Mac. Washington's Gardens at Mount Vernon. Houghton Mifflin, 1999. ISBN 978-0395929704

- Lewis, Taylor Biggs. Washington's Mount Vernon. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1973. ISBN 978-0030039614

- Wilstach, Paul and Paul Washington. Mount Vernon: Washington's Home and the Nation's Shrine. Doubleday, Page and Company, 1916. ASIN B000K5Q9WI

External links

All links retrieved June 2, 2025.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.