Il-Khan dynasty

The Ilkhanate (also spelled Il-khanate or Il Khanate in Persian: سÙسÙ٠اÛÙخاÙÛ), was one of the four khanates within the Mongol Empire. It was centered in Persia, including present-day Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkey, and western Pakistan. It was based, originally, on Genghis Khan's campaigns in the Khwarezmid Empire in 1219-1224, and the continual expansion of Mongol presence under the commands of Chormagan, Baiju, and Eljigidei. Il-Khan means "subordinate Khan" and the dynasty was in theory under the authority of the Great Khan, although they lost contact with him. They unified much of Iran following several hundred years of political fragmentation. Adopting Islam, they oversaw what has been described as a Renaissance in Iran. They oscillated between Sunni and Shi'a Islam, though after the beginning of the Safavid dynasty Iran would become officially Shi'a. Although the Khanate disintegrated, it brought stability to the region for about a century. Their rule is usually dated from 1256 to 1353.

Hulegu

After a battle against the Turks in 1243, the Mongols had occupied Anatolia, and the Sultanate of Rum became a vassal of what would later become the Ilkhanate Mongols.

The founder of the Ilkhanate dynasty was Hulegu Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan and brother of Mongke khan. Taking over from Baiju in 1255 or 1256, he had been charged with subduing the Muslim kingdoms to the west "as far as the borders of Egypt." In 1258, they effectively ended the Abbasid caliphate when they took Baghdad, although a surviving member of the family fled to Egypt where Abbasidâs continued to use the title caliph until 1517, when they passed it on to the Ottoman Emperor. This occupation led the Turkmens to move west to escape from the Mongolian tribes, which eventually gave birth to the Ottomans.

Hulegu then returned to the Persian heartland and established his dynasty. His expedition towards Egypt, however, was halted in Palestine in 1260 by a major defeat at the Battle of Ain Jalut at the hands of the Mamluks of Egypt.

Early il-Khanate

The term il-Khan means "subordinate khan" and refers to their initial deference to Mongke as great khan and ultimate sovereign of the entire empire. Hulegu's descendants ruled Persia for the next eighty years, beginning as shamanists, then Buddhists and ultimately converting to Islam. However, the Il-khans remained opposed to the Mamluks (who had defeated both Mongol invaders and crusaders), but were never able to gain significant ground against them, eventually being forced to give up their plans to conquer Syria, and their stranglehold over their vassals the Sultanate of Rum and the Armenian kingdom in Cilicia. This was due to the hostility of the khanates to the north and eastâthe Chagatai khanate in Mughulistan and the Blue Horde of Batu threatened the Il-khanate in the Caucasus and Transoxiana, preventing expansion westward. Even under Hülegü's reign, the Ilkhanate was engaged in open warfare in the Caucasus with the Mongols in the Russian steppes.

Franco-Mongol alliance

Many attempts towards the formation of a Franco-Mongol alliance were made between the courts of Western Europe and the Mongol Empire (primarily the Ilkhanate) in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, starting from around the time of the Seventh Crusade. United in their opposition to the Muslims (mainly the Mamluks), the Ilkhanate and the Franks (designating all western Europeans, but especially those associated with the Crusader States)[1] were only fleetingly and briefly successful at effective cooperation against their common enemy. The fundamental nature of the alliance doomed it from the start and the changing politics of the Middle East sealed its fate.[2]

Conversion to Islam

In the period after Hulegu, the il-khans increasingly adopted Tibetan Buddhism. Christian powers were encouraged by what appeared to be a favoring of Nestorian Christianity but this probably went no deeper than their traditional even handedness (Medieval Persia 1040-1797; David Morgan, 64). Thus the Il-khans were markedly out of step with the Muslim majority they ruled. However, Ghazan, shortly before he overthrew Baidu, converted to Islam and his official favoring of Islam went along with a marked attempt to bring the regime closer to the non-Mongol majority. Christian and Jewish subjects however lost their equal status with Muslims and again had to pay the poll tax. Buddhists had the starker choice of conversion or expulsion.[3] In foreign relations however things this conversion had no effect and Ghazan fought the Mamluks for Syria. For the most part, this policy continued under his brother Ãljeitü despite suggestions that he might seek to favor the Shiah version of Islam. He succeeded in conquering Gilan on the Caspian coast and his magnificent tomb in Soltaniyeh remains the best known monument of Ilkhanid rule in Persia.

Controversy surrounding Conversion

One of the most distinguished scholars of the time, Ibn Taymiyyah refused to recognize the legitimacy of the Mongolâs claim to be Muslim, and encouraged jihad against them. He considered their claim to be true Muslim was compromised by their adherence to the law of Yasa Code, rather than to Sharia, Islamic Law. He introduced the idea that the term jahilia (ignorance) could be used of Mongol society, and that it was a religious duty to oppose them. He also opposed alliances with the Christian Crusaders, and with Shiâa although his own Sultan was attempting to foster an alliance with the latter. Tayymiyyah moved to Damascus in 1268, then under the Mamluks of Egypt who had halted the Mongol's advance east in 1260 when they won the Battle of Ain Jalut. In 1300, he was dispatched to Cairo to recruit support for a war against the Mongols. That year he was also part of the resistance against the Mongol attack on Damascus and personally went to the camp of the Mongol general to negotiate release of captives, insisting that Christians as âprotected peopleâ as well as Muslims should be released, despite his generally hostile attitude towards them. In 1305, he took part in the anti-Mongol Battle of Shakhab. In 1400, Timur succeeded in sacking Damascus, despite the best efforts of Ibn Khaldun to negotiate a truce.

Disintegration

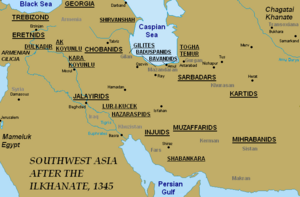

After Abu Sa'id's death in 1335, the khanate began to disintegrate rapidly, and split up into several rival successor states, most prominently the Jalayirids. The last of the obscure Il-khan pretenders was assassinated in 1353. Timur later carved a state from the Jalayirids, ostensibly to restore the old khanate.

The historian Rashid al-Din of whom Mahmud Ghazan was patron wrote a universal history for the khans around 1315 which provides much material for their history.

Il-Khanid Dynasty rulers

- Hülegü (1256-1265)

- Abaqa (1265-1282)

- Ahmad Tegüder (1282-1284)

- Arghun (1284-1291)

- Gaykhatu (1291-1295)

- Baydu (1295)

- Mahmud Ghazan (1295-1304)

- Muhammad Khodabandeh (Oljeitu) (1304-1316)

- Abu Sa'id Bahadur (1316-1335)

Post-Ilkhanate rulers

After the Ilkhanate, the regional states established during the disintegration of the Il-khanate raised their own candidates as claimants.

- Arpa Ke'ün (1335-1336)

- Musa (1336-1337) (puppet of 'Ali Padshah of Baghdad)

- Muhammad (1336-1338) (Jalayirid puppet)

- Sati Beg (1338-1339) (Chobanid puppet)

- Sulayman (1339-1343) (Chobanid puppet, recognized by the Sarbadars 1341-1343)

- Jahan Temur (1339-1340) (Jalayirid puppet)

- Anushirwan (1343-1356) (non-dynastic Chobanid puppet)

- Ghazan II (1356-1357) (known only from coinage)

Claimants from eastern Persia (Khurasan):

- Togha Temür (c. 1338-1353) (recognized by the Kartids 1338-1349; by the Jalayirids 1338-1339, 1340-1344; by the Sarbadars 1338-1341, 1344, 1353)

- Luqman (1353-1388) (son of Togha Temür)

See Also

Notes

- â Between the eleventh to the fifteenth century, the Crusaders were usually called Franks. More broadly the term applied to any persons originating in Catholic Western Europe (medieval Middle Eastern history). The term led to derived usage by other cultures, such as Farangi, firang, farang and barang. "The term [Frank] was used by all the populations of the eastern Mediterranean to designate the totality of the Crusaders as well as the settlers." Riley-Smith, Jonathan Atlas des Croisades, Paris: Autrememt, 1996.

- â "Despite numerous envoys and the obvious logic of an alliance against mutual enemies, the papacy and the Crusaders never achieved the often-proposed alliance against Islam." Atwood, p. 583, "Western Europe and the Mongol Empire."

- â David Morgan, Medieval Persia 1040-1797 (London: Longman, 1998, ISBN 9780582014831), 72.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Amitai-Preiss, R. Mongols and Mamluks: The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War 1260-1281. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 9780521462266

- Atwood, Christopher P. The Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. NY: Facts on File, Inc. 2004. ISBN 0-8160-4671-9

- Bosworth, C. E. The New Islamic Dynasties, New York: Columbia University Press, 1996. ISBN 9780231107143

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.