Betsy Ross

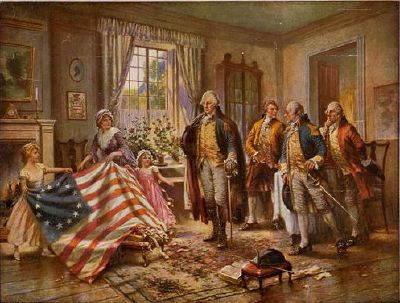

Betsy Ross (January 1, 1752 - January 30, 1836) was an American woman who is said to have sewn the first American flag. Three members of a secret committee from the Continental Congress came to call upon her. Those representatives, George Washington, Robert Morris, and George Ross, asked her to sew the first flag. This meeting occurred in her home some time late in May 1777. George Washington was then commander of the Continental Army. Robert Morris, an owner of vast amounts of land, was perhaps the wealthiest citizen in the Colonies. Colonel George Ross was a respected Philadelphian and also the uncle of her late husband, John Ross.

Early years

Elizabeth ("Betsy") Griscom was born on January 1, 1752, to Samuel Griscom (1717–1793) and Rebecca James Griscom (1721–1793) on the Griscom family farm in Gloucester City, New Jersey.[1] The family moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, when she was very young.[2] She was the eighth of 17 children, of whom only nine survived childhood.

Members of Ross' family were devout Quakers. Her father was a master architect. Ross attended Friends schools, where she learned reading, writing, and sewing. Although Ross is often referred to as a seamstress, she was actually a trained upholsterer. After completing her formal education at a school for Quaker children, Ross went on to apprentice to John Webster, a talented and popular Philadelphia upholsterer. She spent several years with Webster and learned to make and repair curtains, bedcovers, tablecloths, rugs, umbrellas, and Venetian blinds, as well as working on other sewing projects.

First marriage

While she was working as an apprentice upholsterer, she fell in love with another apprentice, John Ross, who was the son of the rector at Christ Church Pennsylvania and a member of the Episcopal clergy. In those times the Quakers disapproved strongly of interdenominational marriages. However, like her mother and father, Betsy eloped with John Ross in 1773 across the Delaware River to New Jersey, where they were married by Benjamin Franklin's son, William Franklin. The couple was subsequently disowned by Ross' Quaker meeting.

The young couple returned to Philadelphia and opened their own upholstery business in 1774. Competition was stiff and business slow. Ross and John attended Christ Church and their pew was next to George Washington's family pew. When the American Revolution began, John joined the militia. He was assigned to guard ammunition stores along the Delaware River. Unfortunately, the gunpowder he was guarding exploded and he eventually died on January 21, 1776.

Legend of sewing the first flag

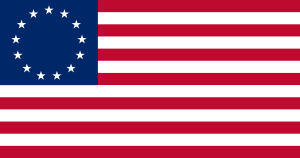

In May of 1777, Ross received a visit from George Washington, George Ross, and Robert Morris of the Second Continental Congress. She was acquainted with Washington through their mutual worship at Christ Church and George Ross was John's uncle. Although there is no record of any such committee, the three men supposedly announced they were a "Committee of Three" and showed her a suggested design that was drawn up by Washington in pencil. The design had six-pointed stars, and Ross, the family story goes, suggested five-pointed stars instead because she could make a five-pointed star in one snip. The flag was sewn by Ross in her parlor. The flag's design was specified in the June 14, 1777 Flag Resolution of the Second Continental Congress, and flew for the first time on September 3, 1777.

No contemporary record of this meeting was made. No "Betsy Ross flag" of thirteen stars in a circle exists from 1776. Historians have found at least 17 other flag makers in Philadelphia at the time. The Betsy Ross story is based solely on oral affidavits from her daughter and other relatives and made public in 1870 by her grandson, William J. Canby. Canby presented these claims in a paper read before the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. No primary sources of the time; letters, journals, diaries, newspaper articles, official records, or business records have surfaced since 1870 confirming or disproving the story. The only further supporting documentation that Betsy Ross was involved in federal flag design is the Pennsylvania State Navy Board commissioning her for work in making "ships colors & c." in May 1777.

Some historians believe it was Francis Hopkinson and not Betsy Ross who designed the official "first flag" of the United States 13 red and white stripes with 13 stars in a circle on a field of blue. Hopkinson was a member of the Continental Congress, a heraldist, a designer of the Great Seal of the State of New Jersey, one of the designer of the Great Seal of the United States, which contains a blue shield with 13 diagonal red and white stripes and 13 five-pointed stars and a signer of the Declaration of Independence.[3]

Later Life

After her husband John's death, Ross joined the "Fighting Quakers" which, unlike traditional Quakers, supported the war effort. In June 1777, she married sea captain Joseph Ashburn at Old Swedes Church in Philadelphia.

Collateral evidence to the claim that Ross indeed provided significant design input in the flag is provided by reference to Ashburn's family coat of arms. The Ashburn crest provides a stars and bars motif not unlike Old Glory itself.[4]

As was their custom and by royal decree, British soldiers forcibly occupied the Ross's house when they controlled the city in 1777.

The couple had two daughters together. Captain Ashburn was captured by the British while procuring supplies for the Continental Army and was sent to Old Mill Prison, where he died in March 1782, several months after the surrender of the British commander in the field, General Charles Cornwallis at Yorktown.

In May 1783, Ross married John Claypoole, an old friend who had told her of Ashburn's death. The couple had five daughters together.

In 1793 Ross’s mother, father, and sister died within days of each other from the yellow fever, left Ross to raise her young niece. John Claypool suffered a devastating stroke in 1800. He survived the stroke, but was bedridden and required constant nursing care for the next 17 years. In 1812, Ross and John’s young and newly widowed daughter, Clarissa, moved into their home along with her five young children and a sixth on the way.

When John Claypool died in 1817, both he and Ross were 65. Ross, however, lived until 1836 working at the upholstery business until she was 76. She died, then completely blind, at the age of 84.

Married three times, Ross was also buried in three different locations: the Free Quaker burial ground on South Fifth Street near Locust, Mt. Moriah (formerly Mt. Claypool) Cemetery, and now on Arch Street in the courtyard adjacent to the Betsy Ross House. Despite being one of the three most visited tourist sites in Philadelphia, the claim that Ross once lived at her current place of rest is a matter of dispute.[5]

United States Flag

The flag is customarily flown year-round from most public buildings, and it is far from unusual to find private houses flying full-size flags. Some private use is year-round, but becomes widespread on civic holidays like Memorial Day (May 30), Veterans Day (November 11), Presidents' Day (February 22), Flag Day (June 14), and on Independence Day (July 4). On Memorial Day it is common to place small flags by war memorials and next to the graves of U.S. war dead.

Places of continuous display

By presidential proclamation, acts of Congress, and custom, the American flag is displayed continuously at the following locations:

- Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine (Baltimore, Maryland; 15-star/15-stripe flag), Presidential Proclamation No. 2795, July 2, 1948.

- Flag House Square (Baltimore, Maryland–15-star/15-stripe flag)–Public Law 83-319 (approved March 26, 1954).

- United States Marine Corps War Memorial (Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima), Arlington, Virginia (Presidential Proclamation No. 3418, June 12, 1961).

- Lexington, Massachusetts Town Green (Public Law 89-335, approved November 8, 1965).

- The White House, Washington, D.C. (Presidential Proclamation No. 4000, September 4, 1970).

- Fifty U.S. Flags are displayed continuously at the Washington Monument, Washington, D.C. (Presidential Proclamation No. 4064, July 6, 1971, effective July 4, 1971).

- By order of Richard Nixon at United States Customs Service Ports of Entry that are continuously open (Presidential Proclamation No. 4131, May 5, 1972).

- By Congressional decree, a Civil War era flag (for the year 1863) flies above Pennsylvania Hall (Old Dorm) at Gettysburg College. This building, occupied by both sides at various points of the Battle of Gettysburg, served as a lookout and battlefield hospital.

- Grounds of the National Memorial Arch in Valley Forge National Historic Park, Valley Forge, Pennsylvania (Public Law 94-53, approved July 4, 1975).

- Mount Slover limestone quarry (Colton Liberty Flag), in Colton, California (Act of Congress). First raised July 4, 1917.

- Washington Camp Ground, part of the former Middlebrook encampment, Bridgewater, New Jersey, Thirteen Star Flag, by Act of Congress.

- By custom, at the home, birthplace, and grave of Francis Scott Key, all in Maryland.

- By custom, at the Worcester, Massachusetts war memorial.

- By custom, at the plaza in Taos, New Mexico, since 1861.

- By custom, at the United States Capitol since 1918.

- By custom, at Mount Moriah Cemetery in Deadwood, South Dakota.

- In addition, the American flag is presumed to be in continual display on the surface of the Earth's Moon, having been placed there by the astronauts of Apollo 11, Apollo 12, Apollo 14, Apollo 15, Apollo 16, and Apollo 17. It is possible that Apollo 11's flag was knocked down by the force of return to lunar orbit.

Notes

- ↑ William D. Timmins and Robert W. Yarrington, Betsy Ross: The Griscom Legacy (Woodston, NJ: Salem County Cultural and Heritage Commission, 1983), 127.

- ↑ John Balderston Harker, Betsy Ross’s Five Pointed Star: Elizabeth Claypoole, Quaker Flag Maker — A Historical Perspective (Melbourne Beach, FL: Canmore Press, 2005, ISBN 978-1887774154), 28.

- ↑ The Flag of the United States of America Retrieved November 23, 2021.

- ↑ Ashburn History, Family Crest & Coats of Arms House of Names. Retrieved November 23, 2021.

- ↑ Was This Her House? Betsy Ross and the American Flag. Retrieved November 23, 2021.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Harker, John Balderston. Betsy Ross’s Five Pointed Star: Elizabeth Claypoole, Quaker Flag Maker — A Historical Perspective. Melbourne Beach, FL: Canmore Press, 2005. ISBN 978-1887774154

- Leepson, Marc. Flag: An American Biography. New York: Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin's Press, 2005. ISBN 0312323093

- Timmins, William D., and Robert W. Yarrington. Betsy Ross: The Griscom Legacy. Woodston, NJ: Salem County Cultural and Heritage Commission, 1983. ASIN B004BJ9N3G

External links

All links retrieved September 29, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.