Anshi, Wang

(copy, credit) |

Laura Brooks (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Claimed}} | {{Claimed}} | ||

| + | {{epname|Anshi, Wang}} | ||

{|cellpadding=3px cellspacing=0px bgcolor=#f7f8ff style="float:right; border:2px solid; margin:5px" | {|cellpadding=3px cellspacing=0px bgcolor=#f7f8ff style="float:right; border:2px solid; margin:5px" | ||

!style="background:#ccf; border-top:2px solid; border-bottom:2px solid" colspan=2|[[Chinese name|Names]] | !style="background:#ccf; border-top:2px solid; border-bottom:2px solid" colspan=2|[[Chinese name|Names]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

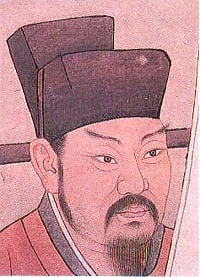

| + | |colspan=2 align=center style="border-top:1px solid"|[[Image:Wang Anshi.jpg|200px|Wáng Ānshí]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

|align=right|[[Chinese surname|Xìng 姓]]:||Wáng 王 | |align=right|[[Chinese surname|Xìng 姓]]:||Wáng 王 | ||

| Line 9: | Line 12: | ||

|align=right|[[Courtesy name|Zì 字]]:||Jièfǔ 介甫 | |align=right|[[Courtesy name|Zì 字]]:||Jièfǔ 介甫 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |align=right|[[Chinese style name|Hào 號]]:||Bànshān Lǎorén 半山老人<br>(Oldman Half-a-Mountain) | + | |align=right|[[Chinese style name|Hào 號]]:||Bànshān Lǎorén 半山老人<br/>(Oldman Half-a-Mountain) |

|- | |- | ||

|align=right|[[Posthumous name|Shì 謚]]:||Wén 文¹ | |align=right|[[Posthumous name|Shì 謚]]:||Wén 文¹ | ||

| Line 18: | Line 21: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|colspan=2 align=left |<small>''2. hence referred to as Wáng Jīnggōng'' </small>王荊公<small/> | |colspan=2 align=left |<small>''2. hence referred to as Wáng Jīnggōng'' </small>王荊公<small/> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|} | |} | ||

| − | {{Chinese | + | '''Wáng Ānshí''' ({{zh-cw|c=王安石|w=Wang An-shih}}) (1021 - May 21, 1086 <ref>6th day of the 4th month of Yuanyou 1 (元祐元年四月六日), which corresponds to May 21, 1086 in the [[Julian calendar]].</ref>) was a [[China|Chinese]] economist, statesman, [[Chancellor of China|chancellor]] and poet of the [[Song Dynasty (960-1279)|Song Dynasty]] who attempted some controversial, major [[socioeconomics|socioeconomic]] [[social reform|reform]]s. These reforms constituted the core concepts and motives of the Reformists, while their nemesis, Chancellor [[Sima Guang]], led the Conservative faction against them. |

| + | |||

| + | ==Background== | ||

| + | Under the Song Dynasty, the unprecedented development of large [[estate (land)|estate]]s, whose owners managed to evade paying their share of [[tax]]es, resulted in an increasingly heavy burden of taxation falling on the [[peasantry]]. The drop in state revenues, a succession of [[budget]] [[deficit]]s, and widespread [[inflation]] prompted the [[Emperor Shenzong of Song]] to seek advice from Wang. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Early career== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Though Wang was from the south, he came from a family of ''[[jinshi]]'' degree winners. He himself placed fourth in the palace degree exams in 1042. He spent the first twenty years of his career in regional government in the Lower [[Yangtze River|Yangtze]] region. During this time, he gained practical experience in meeting the needs of the common people. This experience guided his analysis in formulating solutions to what ailed Song society. <ref> [Mote ch. 6] </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Major Reform== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Wang believed that the [[state]] was responsible for providing its [[citizen]]s the essentials for a decent living standard: "The state should take the entire management of [[commerce]], [[industry]], and [[agriculture]] into its own hands, with a view to succoring the working classes and preventing them from being ground into the dust by the rich." {{Fact|date=June 2007}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Wang came to power in 1069. It was here that he formulated and promulgated New Policies (''xin fa'' 新法). His reforms were classified into three groups: 1) state finance and trade, 2) defense and social order, and 3) education and improving of governance. | ||

| + | Some of the finance reforms included paying cash for labor in place of corvee labor, increase the minting of copper coins, improve management of trade, implementing plans to lend farmers money when they planted to be repaid at harvest. He believed that the common people and their well being were the key to the strength of the state and thus he made it a priority to address their needs. <ref> [Mote p. 139] </ref> To destroy [[speculation]] and break up the [[monopoly|monopolies]], he also initiated a system of fixed commodity prices; and he appointed boards to [[regulation|regulate]] [[wage]]s and plan pensions for the aged and unemployed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A centerpiece of defense and social order reforms was the institution of the [[baojia system]] of organizing households. This was done to ensure collective responsibility in society and was later used to strengthen local defense. He also proposed the creation of systems to breed military horses, the more efficient manufacture of weapons and training of the militia. <ref> [Mote p. 140] </ref> | ||

| − | + | To improve education and government, he sought to break down the barrier between clerical and official careers as well as improving their supervision to prevent connections being used for personal gain. Tests in law, military affairs and medicine were added to the examination system, with mathematics added in 1104. The National Academy was transformed into a real school rather than simply a holding place for officials waiting for appointments. However, there was deep-seated resistance to the education reforms as it hurt bureaucrats coming in under the old system <ref> [Mote p. 141] </ref> | |

| − | + | Modern observers have noted how remarkably close his theories were to modern concepts of the [[welfare state]] and [[planned economy]]. {{Fact|date=June 2007}} | |

| + | |||

| + | ==Wang’s Downfall== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Although Wang had the alliance of such prominent court figures as [[Shen Kuo]], imperial [[scholar-officials]] such as [[Su Dongpo]] and [[Ouyang Xiu]] bitterly opposed these reforms on the grounds of tradition. They believed Wang's reforms were against the moral fundamentals of the [[Two Emperors]] and would therefore prevent the Song from experiencing the prosperity and peace of the ancients. The tide tilted in favor of the conservatives due to renewed foreign conflict. He was even temporarily removed from power and imprisoned in 1075. {{Fact|date=June 2007}} | ||

| − | + | Like many Chinese officials of the era, he had an up and down career, but the beginning of the end came in 1074. A famine in northern China drove many farmers off their lands. Their circumstances were made worse by the debts they had incurred from the seasonal loans granted under Wang’s reform initiatives. The situation was made even worse when local officials insisted on collecting on the loans as the farmers were leaving their land. This crisis was depicted as being Wang’s fault. The [[empress dowager]] was also an opponent of Wang. Wang wanted to resign, but the emperor still supported him, giving him high honors and an appointment to Jiangning (present-day [[Nanjing]].) | |

| − | + | He was recalled by the emperor the following year, but now he was seen as vulnerable and was openly attacked from groups of conservatives. Wang returned to Nanjing, which be preferred to Kaifeng. He wrote and engaged in scholarship through to his death in 1086. <ref> [Mote p. 141-42] </ref> | |

| − | + | With Shenzhong's death in 1085, Wang was permanently ousted and the New Policies rolled back. | |

| − | + | ==Poet== | |

In addition to his political achievements, Wang Anshi was a noted poet. He wrote poems in the ''[[Shi (poetry)|shi]]'' form, modelled on those of [[Du Fu]]. He was traditionally classed as one of the ''Eight Great Prose Masters of the [[Tang Dynasty|Tang]] and [[Song Dynasty|Song]]'' (唐宋八大家). | In addition to his political achievements, Wang Anshi was a noted poet. He wrote poems in the ''[[Shi (poetry)|shi]]'' form, modelled on those of [[Du Fu]]. He was traditionally classed as one of the ''Eight Great Prose Masters of the [[Tang Dynasty|Tang]] and [[Song Dynasty|Song]]'' (唐宋八大家). | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Notes== |

| − | |||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | * Mote, F.W. ''Imperial China: 900-1800''Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press 1999 ISBN 9780674445154 | ||

| + | |||

| + | == External Links == | ||

| + | |||

| + | * [http://www.pacificrim.usfca.edu/research/perspectives/anderson.pdf To Change China: A Tale of Three Reformers] Retrieved August 20, 2007. | ||

| + | * [http://www.pacificrim.usfca.edu/research/perspectives/index.html ''Asia Pacific: Perspectives''] Retrieved August 20, 2007. | ||

| + | |||

{{start box}} | {{start box}} | ||

| − | {{succession box | before = to be added | title = [[Chancellor of China|Prime Minister of China]]| years = | + | {{succession box | before = to be added | title = [[Chancellor of China|Prime Minister of China]]| years = 1070–1075 | after = to be added}} |

| − | {{succession box | before = to be added| title = [[Chancellor of China|Prime Minister of China]]| years = | + | {{succession box | before = to be added| title = [[Chancellor of China|Prime Minister of China]]| years = 1076–1085 | after = [[Sima Guang]]}} |

{{end box}} | {{end box}} | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:History and biography]] |

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Biography]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{credit| | + | {{credit|149697700}} |

Revision as of 04:11, 20 August 2007

| Names | |

|---|---|

| |

| Xìng 姓: | Wáng 王 |

| Míng 名: | Ānshí 安石 |

| Zì 字: | Jièfǔ 介甫 |

| Hào 號: | Bànshān Lǎorén 半山老人 (Oldman Half-a-Mountain) |

| Shì 謚: | Wén 文¹ |

| title: | Jīngguógōng 荊國公² |

| 1. hence referred to as Wáng Wéngōng 王文公 | |

| 2. hence referred to as Wáng Jīnggōng 王荊公 | |

Wáng Ānshí (Chinese: 王安石; Wade-Giles: Wang An-shih) (1021 - May 21, 1086 [1]) was a Chinese economist, statesman, chancellor and poet of the Song Dynasty who attempted some controversial, major socioeconomic reforms. These reforms constituted the core concepts and motives of the Reformists, while their nemesis, Chancellor Sima Guang, led the Conservative faction against them.

Background

Under the Song Dynasty, the unprecedented development of large estates, whose owners managed to evade paying their share of taxes, resulted in an increasingly heavy burden of taxation falling on the peasantry. The drop in state revenues, a succession of budget deficits, and widespread inflation prompted the Emperor Shenzong of Song to seek advice from Wang.

Early career

Though Wang was from the south, he came from a family of jinshi degree winners. He himself placed fourth in the palace degree exams in 1042. He spent the first twenty years of his career in regional government in the Lower Yangtze region. During this time, he gained practical experience in meeting the needs of the common people. This experience guided his analysis in formulating solutions to what ailed Song society. [2]

Major Reform

Wang believed that the state was responsible for providing its citizens the essentials for a decent living standard: "The state should take the entire management of commerce, industry, and agriculture into its own hands, with a view to succoring the working classes and preventing them from being ground into the dust by the rich." [citation needed]

Wang came to power in 1069. It was here that he formulated and promulgated New Policies (xin fa 新法). His reforms were classified into three groups: 1) state finance and trade, 2) defense and social order, and 3) education and improving of governance. Some of the finance reforms included paying cash for labor in place of corvee labor, increase the minting of copper coins, improve management of trade, implementing plans to lend farmers money when they planted to be repaid at harvest. He believed that the common people and their well being were the key to the strength of the state and thus he made it a priority to address their needs. [3] To destroy speculation and break up the monopolies, he also initiated a system of fixed commodity prices; and he appointed boards to regulate wages and plan pensions for the aged and unemployed.

A centerpiece of defense and social order reforms was the institution of the baojia system of organizing households. This was done to ensure collective responsibility in society and was later used to strengthen local defense. He also proposed the creation of systems to breed military horses, the more efficient manufacture of weapons and training of the militia. [4]

To improve education and government, he sought to break down the barrier between clerical and official careers as well as improving their supervision to prevent connections being used for personal gain. Tests in law, military affairs and medicine were added to the examination system, with mathematics added in 1104. The National Academy was transformed into a real school rather than simply a holding place for officials waiting for appointments. However, there was deep-seated resistance to the education reforms as it hurt bureaucrats coming in under the old system [5]

Modern observers have noted how remarkably close his theories were to modern concepts of the welfare state and planned economy. [citation needed]

Wang’s Downfall

Although Wang had the alliance of such prominent court figures as Shen Kuo, imperial scholar-officials such as Su Dongpo and Ouyang Xiu bitterly opposed these reforms on the grounds of tradition. They believed Wang's reforms were against the moral fundamentals of the Two Emperors and would therefore prevent the Song from experiencing the prosperity and peace of the ancients. The tide tilted in favor of the conservatives due to renewed foreign conflict. He was even temporarily removed from power and imprisoned in 1075. [citation needed]

Like many Chinese officials of the era, he had an up and down career, but the beginning of the end came in 1074. A famine in northern China drove many farmers off their lands. Their circumstances were made worse by the debts they had incurred from the seasonal loans granted under Wang’s reform initiatives. The situation was made even worse when local officials insisted on collecting on the loans as the farmers were leaving their land. This crisis was depicted as being Wang’s fault. The empress dowager was also an opponent of Wang. Wang wanted to resign, but the emperor still supported him, giving him high honors and an appointment to Jiangning (present-day Nanjing.)

He was recalled by the emperor the following year, but now he was seen as vulnerable and was openly attacked from groups of conservatives. Wang returned to Nanjing, which be preferred to Kaifeng. He wrote and engaged in scholarship through to his death in 1086. [6]

With Shenzhong's death in 1085, Wang was permanently ousted and the New Policies rolled back.

Poet

In addition to his political achievements, Wang Anshi was a noted poet. He wrote poems in the shi form, modelled on those of Du Fu. He was traditionally classed as one of the Eight Great Prose Masters of the Tang and Song (唐宋八大家).

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Mote, F.W. Imperial China: 900-1800Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press 1999 ISBN 9780674445154

External Links

- To Change China: A Tale of Three Reformers Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- Asia Pacific: Perspectives Retrieved August 20, 2007.

| Preceded by: to be added |

Prime Minister of China 1070–1075 |

Succeeded by: to be added |

| Preceded by: to be added |

Prime Minister of China 1076–1085 |

Succeeded by: Sima Guang |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.