Difference between revisions of "Suffering" - New World Encyclopedia

David Doose (talk | contribs) |

David Doose (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

| − | We have had and will continue to have religious wars. Wars cause suffering. Some religions reject the use or development of pain relieving drugs. Alienation results when, because of conviction, one abandons one’s birth religion. Consequently some parents or children disown the other because of their new religious allegiance. This also occurs when one begins to interpret and live the religion differently than the majority. There is the phenomenon known as the ''Dark Night of the Soul'' | + | We have had and will continue to have religious wars. Wars cause suffering. Some religions reject the use or development of pain relieving drugs. Alienation results when, because of conviction, one abandons one’s birth religion. Consequently some parents or children disown the other because of their new religious allegiance. This also occurs when one begins to interpret and live the religion differently than the majority. There is the phenomenon known as the ''Dark Night of the Soul'' <ref>See, ''Dark Night of the Soul'' by St. John of the Cross ; translated and edited, with an introduction, by E. Allison Peers ; from the critical edition of P. Silverio de Santa Teresa. New York : Image Books/Doubleday, 1990. ISBN 0585035660 </ref> |

where an individual loses all sense of purpose and feelings for their religious life. Deep suffering occurs as the individual seeks to make her or his way in a life seemingly without direction because one feels that what formerly made sense and provided direction no longer exists. | where an individual loses all sense of purpose and feelings for their religious life. Deep suffering occurs as the individual seeks to make her or his way in a life seemingly without direction because one feels that what formerly made sense and provided direction no longer exists. | ||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

In economics the question of suffering is addressed by the topics of [[Quality of life|Well-being or Quality of life]], [[Welfare economics]], [[Measuring well-being]], [[Gross National Happiness]], and [[Genuine Progress Indicator]]. | In economics the question of suffering is addressed by the topics of [[Quality of life|Well-being or Quality of life]], [[Welfare economics]], [[Measuring well-being]], [[Gross National Happiness]], and [[Genuine Progress Indicator]]. | ||

| − | "[[Pain and suffering]]" is the term used in the field of law to refer to the mental anguish and/or physical pain endured by the plaintiff as a result of injury for which the plaintiff seeks redress.<ref>http://www5.aaos.org/oko/vb/online_pubs/professional_liability/glossary.cfm</ref> | + | "[[Pain and suffering]]" is the term used in the field of law to refer to the mental anguish and/or physical pain endured by the plaintiff as a result of injury for which the plaintiff seeks redress.<ref>American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons http://www5.aaos.org/oko/vb/online_pubs/professional_liability/glossary.cfm Retrieved March 4, 2007.</ref> |

==Biological perspective== | ==Biological perspective== | ||

Revision as of 04:08, 4 March 2007

Suffering is usually described as a negative basic feeling or emotion that involves a subjective character of unpleasantness, aversion, harm or [threat of harm.

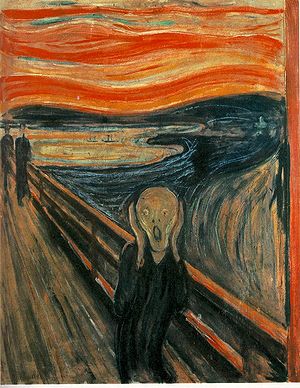

The Scream by Edvard Munch has become a symbol of the mental suffering of modern man.

- Suffering may be said physical or mental, depending whether it refers to a feeling or emotion that is linked primarily to the body or to the mind. Examples of physical suffering are pain, nausea, breathlessness, itching[1]. Examples of mental suffering are anxiety, grief, hatred, boredom[2].

- There is much ambiguity in the use of the words pain and suffering. Sometimes they are synonyms and interchangeable. Sometimes they are used in contradistinction to one another: e.g. "pain is inevitable, suffering is optional", "pain is physical, suffering is mental". Sometimes yet, like in the previous paragraph, they are defined in another way.

- The intensity of suffering comes in all degrees, from the triflingly mild to the unspeakably insufferable. Other factors often considered along with intensity are duration and frequency of occurrence.

- People's attitudes toward a suffering may vary hugely according to how much they deem it is light or severe, avoidable or unavoidable, useful or useless, of little or of great consequence, deserved or undeserved, chosen or unwanted, acceptable or unacceptable.

All sentient beings admittedly suffer during their lives, in various manners, and much often dramatically. Therefore, suffering is an important topic in many fields of human activity. Those fields are concerned with, for instance, the personal or social or cultural behaviors related to suffering, the nature or causes of suffering, its meaning or significance, its remedies or management or uses.

Religious perspectives

Wholistic nature of suffering

Language divides a person into body and soul. Sciences divide the human person into areas such as biology, chemistry, psychology, and sociology. Various agencies from government to business separate us into niches, genders, ethnicities, races, and economics. Because so much of western culture takes for granted we are divided, it is difficult to think and act as if we are whole. Thus, in thinking and acting about our own or another’s suffering we usually do so in this context of division and look at life as bits and pieces instead of together and whole.

One common “piece” of suffering is physical pain. Physical pain is usually reduced to another piece of our self: our body. Our body, to its chemistry; our chemistry, to its atoms, atoms to subatomic particles or combinations of atoms such as DNA, cells, and protons. Most in our society focus on one of these pieces to deal with a person’s suffering and, in doing so, lose sight of Mary, John, Dick and Jane as real suffering people as they are medicated for what ails them. In losing sight of the whole person many times we are blinded to other ways to diminish the person’s suffering. If we look at the whole person, all the pieces together, we can reduce suffering, and pain. How do we know this? Through science and experience. Both have constantly shown such things as the presence of a loved one, a reason to live, and how a positive disposition advances physical, mental, and social cures and reduce suffering.

This way of reducing us to one piece of ourselves is called the “machine model.” This is when we talk and try to understand a person as an assemblage of parts that, when suffering, needs fixing because the person is broken. With this way of thinking each of us is the sum of our parts. Another way to think about the human being is the “organic model.” Here we think of ourselves as a living oganism that is more than those individual things we see, feel, and touch. In this model we grow, decay, and are diseased – not broken. Our growth, decay, and suffering are interdependent upon our physical, mental, social, and spiritual environment. We are our relationships to every living and non-living entity past, present, and future. The diminishment of any of these relationships causes suffering. The enlivening of any one of these relationships helps foster a healthy life. The more enlivened authentic relationships are fostered, the healthier we become.

There are five manifestations of these relationships: our physical self, our social self, our mental self, our self worth, our whole (purposeful) self. These relationships evidence suffering as we feel pain, alienation, ignorance, injustice, and purposelessness.

Answers to why we suffer

There are four famous answers to the question of why we suffer.

1. It's absurd.

Life is absurd. Death is absurd. It’s absurd to even ask the question about suffering. After all, life is just one boring thing after another, so what is the use of even thinking about it?

There is no use thinking about it, but there is a benefit to doing something about it. We prove we can beat life's absurdity. We get up in the morning and face the boredom of life knowing that in facing it we prove we will not let its absurdity do us in. To be human and alive is to thumb our nose at the boredom, absurdity, and stupidity of life itself and any of the suffering inherent in living it.

The ancient myth of Sisyphus is a good example of this response to our question. The story is told that Sisyphus was condemned to push a large boulder up an enormous mountain. Through rain, snow, sleet, cold and hot he strained to get the boulder to the top of the mountain. Day after day, night after night his only goal was to push the boulder to the top. Strained muscles, scraped knees and arms, bruised shoulders and face, did not stop him. Every day he pushed. Every day he inched his way to the top. Then one day he reached the top. In exultation, he paused in triumph. While he paused, the boulder rolled down the mountain. His eternity was to push the boulder to the top. His humanity was to look from the top of the mountain at the boulder below and with shoulders square, turn to begin again. Death? Suffering? Future? - Absurd! But damn it, I'll keep pushing.

2. That's life.

Some see life as a set of immutable laws, patterns, relationships, or recognized expectations that, if broken, result in suffering or death. The immutable laws may be titled natural, physical, social; they may be seen as the deep and expected relationships between all beings. While the "It's absurd" perspective looks at life in a negative way, this perspective may have a positive or negative outlook on life. But, it is accepting of what causes the suffering because it sees all of life in a give-and-take perspective where everything must be balanced. It is enough to say that the person died of cancer or that the war was caused by people's dislike of their dictator. The future, from this perspective, is determined by the present. There are no surprises. If one does everything that is proper physically, socially, and emotionally then one will live forever. Life is an interlocking network of relationships which, when broken, cause suffering and death.

3. Down Deep We Don't Suffer.

Some believe that everything we feel, see, and touch is not real. Suffering is derived from being too attached to what is passing. All that is real is what is permanent not what is changing. This "permanent" reality may be called "soul" by some; self, by others; god, by still others.

There are many names used to describe this permanency but behind the names there is either a claim that there is some personal individuality which never changes or there is a common shared oneness that we all are. In either case, suffering occurs when we get caught up in this changing world. When we get caught up in our changing individual desires, suffering occurs. Death is the deliverance from this suffering. But awareness that all of this is not real is also a way to move beyond the suffering. To realize that down deep, where the real me is, there is no suffering, is to go beyond all suffering - to be a reality which stands still and there is no difference between past, present, and future.

4. It all fits in somehow.

This perspective is dependent upon our Western culture. It sees time and reality not as some permanent circle, as "down deep we don't suffer," but as a vector, a line going somewhere because it has reasons to go somewhere. Our personal history takes a personal direction that results from the interplay of our freedom, loving, and working with our total environment. We are very much our body, our changing emotions, and our relationships. We would be nothing without these dynamic and enfleshed realities. The "why" question is very important to those who approach life from this perspective because its answer indicates to them the direction of their future and the reasonableness of their suffering. Suffering must fit into something more than one's self. This something may be titled history, God, God's will, the Kingdom of God.

There are many images for the plan but behind the plan is always a suggestion that it is a personal plan. The universe and all of life are the consequence of a relationship between the individual, all living and non-living beings, and that which supports the life and direction of this universe and life. When one asks “Why do we suffer?” from this perspective, the expected answer is along the lines of the answer to such a question as “Why did your parent or friend hang up the phone?” The expected answer is a personal answer involving love, responsibility, value or something similar. The "why" question in the other three perspectives is an impersonal question and looks for an impersonal answer. "Why is she suffering?" in "Its absurd" expects a response of "there is no reason, it doesn't makes sense." "Why is he suffering?" in "That's life" will understand an answer framed in impersonal logic such as "It’s a terrible disease. Everyone dies because of it." "Why is she suffering? in "Down Deep We don't suffer" is a question seldom asked. If asked, the expected reply would indicate that the person has not changed by suffering and perhaps death - that we really never knew her, that suffering is part of the life we live until we dig deeper into life and get to where it is really lived. The "why" question may be asked in the "it all fits in somehow" not expecting an answer.

The way one phrases the unknowns of the causes of suffering is significant. We just don't know what it’s all about. We think that what happened is bad, but we know that even from bad good may come. Or, in a sort of ultimate personal relationship, we describe how God suffered and died and that this seems stupid yet it is believed. Notice that the general, "it all fits in somehow," is accepted, but how it fits becomes lost in the mystery of the stories that are part of this approach.

Historical religious positions

These four answers are really spiritualities: spiritualities of the absurd, of consequence, of illusion, and of providence. When recognized and affirmed as the plot of life they are a spirituality that directs our life. These four answers are also institutionalized in specific historical religious traditions.

Humans have faced suffering since the beginning of time. The manner in which they have responded is embodied in a number of traditions. Traditions are our patterned response to the foundational realities of life. We have traditions of eating, of sleeping, of speaking, and suffering. This patterned response may also be expressed in each of the foundational human realities. Thus we have traditions of bodily care, social ritual, emotional linking, and seeking for meaning associated with suffering. Because suffering is so all encompassing, so involved with the foundational realities of life, the traditions that are deeply involved with this question are those we generally describe as religions. Religious communities have always responded to the whole person when dealing with suffering. Some commentators in the last century, because of their philosophical orientation, suggested that religions always were concerned with the future, especially the afterlife. But, if one looks at the major world religions one sees a wholistic commitment to the alleviation of suffering.

Every religion demands right living from its members. Right living looks toward the diminution of suffering by erasing its immediate cause. It sets the stage for a world free of the suffering caused by humans. Judaism, for instance, has given us many principles of justice and concern. The statement of God in Hosea 6:6 "... what I want is love, not sacrifice," sets the prophetic theme of justice and love for all. And Nathan's statement to David, "You are the man" (2 Samuel 12:7), i.e. you are responsible and accountable to God for the suffering you cause, places the burden upon the individual to relieve suffering. The Christian's obligation vis-a-vis suffering is found both in Jesus' words on the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5:1-12 and Luke 6:20-26) and in his example in healing the blind, the lame, and the deaf. Islam's Five Pillars includes a direct attack on poverty and demands the giving of alms. As the Koran says, "Did he not find you wandering and give you guidance? As for the orphan, then, do him no harm; as for the beggar, turn him not away" (Smriti xciii). For the Hindu, right living consists in specifying duties for each state of life. If lived, they decrease the suffering in the world. In essence, one should cause harm to no one. Buddhism and Hinduism find a common bond in a compassion that seeks unity with the suffering of others in order to destroy all suffering. One of the fundamental teachings in Buddhism is constituted by the Four Noble Truths about dukkha, a term that is usually translated as suffering. The Four Noble Truths state the nature of suffering, its cause, its cessation, and the way to its cessation (this way is called the Noble Eightfold Path). Liberation from suffering is considered essential for leading a holy life and attaining nirvana.

Religions also offer many means of engaging the emotions surrounding suffering and death. This engagement of the emotions is found especially in the tradition of "devotion," and of "mystical union." Not everyone within the various religions engages in these two traditions but they are present in most religions.

"Devotion" is prayer and a lifestyle committed to a significant religious figure— for example, Krishna or Jesus. Prayer is a communication with this most significant religious figure. Our suffering takes on a meaning because of our relationship to this significant religious figure. At the same time our consecration to him or her opens up patterns of endurance, compassion, and forgiveness because we want to base our life upon the object of our devotion who has also suffered.

"Mystical union" is consecration brought to completion by accomplishing oneness with the ultimate in our life. We see this in the Eastern religions, where the ultimate identity of each of us is found in the permanent (Brahman); or in the Far East, in Tao, where we can reach an inner perception of and unity with Tao. The union is with that which is beyond the here and now. In the union, there is no suffering.

The social dimensions of the religion are many— most of which have become enshrined in ritual. The rituals surrounding the preparation of the disposal of the body, the rituals associated with the days and/or weeks following the death, and the prayer rituals within the gathering of the community petitioning for health or comfort. Ritual action copes with suffering in many ways: for example, by enlisting the support of the religious community as in Jewish mourning practices of Shiva or the Catholic Mass; or by placing the sufferer in a positive frame of mind by putting them in contact with their ultimate concern and consequently relativizing the suffering. Some ritual actions are believed to reduce suffering itself, as in forms of faith healing.

Every wholistic approach must also include the human drive to understand the surrounding world. The religious traditions in response to the "why" question have developed such understandings over the centuries. Especially in those religious traditions that acknowledge a personal God (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) there have been various attempts to understand why we suffer, why we die, and what influences our future. There are three basic responses: the instrumental, the punitive, and the redemptive.

The instrumental model of suffering is found, for instance, in the Islamic belief that suffering is an instrument of God's purposes; in Christianity, that God made Jesus perfect through suffering (Hebrews 12:3-10). In any discussion of suffering this way of understanding the "why" of suffering comes to the fore as we tell one another that few good things are produced without pain or as we ask how we can develop into mature persons without suffering. The belief is that suffering is an instrument, sometimes sharp, sometimes blunt, of individual and communal development. A personal God uses it to bring about his goal for humanity.

Suffering considered as punishment changes the emphasis slightly yet significantly. Punishment highlights the judgmental character of a personal God. We suffer because we or others have sinned. Suffering is a way of righting the imbalance of evil over good. As Rabbi Ruba (1500 C.E.) said, "If a man sees that painful suffering visits him, let him examine his conduct." This approach is found in many prayer books of classic religions. In theology, there is a classical problem called the problem of evil: it deals with the difficulty of reconciling the existence of an omnipotent and benevolent God with the existence of evil, of which extreme suffering is often considered one of the worst kinds, especially in innocent children, or in creatures tormented in an eternal hell. Within the Bible, the Book of Job is widely regarded as a profound poetical reflection on the nature and meaning of suffering.

But classic religion is not alone in such an approach: The blood of many people flows in reparation for the sins of their colonial forefathers; a woman in public office is hounded from it for an offense committed in her teens; those who commit crimes against society are punished for past deeds. The model of suffering as a punishment for wrong doing is evident to anyone who makes a child suffer because of some misdeed. It is a short step to complete the circle and ask of the sufferer what he or she has done wrong because suffering is supposedly always linked to wrong doing. As a Sufi saying has it, "When you suffer pain, your conscience is awakened, you are stricken with remorse and pray God to forgive your trespasses."

The belief in suffering as redemptive is found in many stories and songs: Someone takes upon himself or herself the sins and burdens of others so that all will be free of the consequences of sin. In this view, whenever anyone suffers so that others may live, redemption occurs. The prophets of Israel make this clear in describing the role of the Babylonian captivity in the nation's life. Isaiah summarized it when he said: "By his suffering shall my servant justify many, taking their faults on himself." John's Gospel applies this same principle to Christianity when John the Baptist claims that Jesus is the one who takes away the sins of the world. (John 1:29)

Help or hinderence

Religion, when it is authentic to itself, is a direct aid in the reduction of suffering. Sometimes, however, it may intensify the suffering when its role is misunderstood, its devotees closed to the exercise of compassion, or it is used to advance the power of individuals and or groups.

We have had and will continue to have religious wars. Wars cause suffering. Some religions reject the use or development of pain relieving drugs. Alienation results when, because of conviction, one abandons one’s birth religion. Consequently some parents or children disown the other because of their new religious allegiance. This also occurs when one begins to interpret and live the religion differently than the majority. There is the phenomenon known as the Dark Night of the Soul [3]

where an individual loses all sense of purpose and feelings for their religious life. Deep suffering occurs as the individual seeks to make her or his way in a life seemingly without direction because one feels that what formerly made sense and provided direction no longer exists.

Philosophical, Ethical Perspectives

Suffering in philosophy and ethics is addressed in the study of Epicurus, Stoicism, Arthur Schopenhauer, Jeremy Bentham, Hedonic calculus, Utilitarianism, John Stuart Mill, Friedrich Nietzsche's On the Genealogy of Morals, Humanitarianism, Negative utilitarianism, Peter Singer, Richard Ryder’s Painism, and the Philosophy of pain.

Social Science perspective

Social suffering, according to Iain Wilkinson in Suffering - A Sociological Introduction, is increasingly a concern in sociological fields such as medical anthropology, ethnography, mass media analysis, and Holocaust studies.

Ralph Siu, an American author, urged in 1988 the "creation of a new and vigorous academic discipline, called panetics, to be devoted to the study of the infliction of suffering."[4] The International Society for Panetics was founded in 1991 and is dedicated to the study and development of ways to reduce the infliction of human suffering by individuals acting through professions, corporations, governments, and other social groups.

In economics the question of suffering is addressed by the topics of Well-being or Quality of life, Welfare economics, Measuring well-being, Gross National Happiness, and Genuine Progress Indicator.

"Pain and suffering" is the term used in the field of law to refer to the mental anguish and/or physical pain endured by the plaintiff as a result of injury for which the plaintiff seeks redress.[5]

Biological perspective

The process of suffering is associated with many brain structures. For instance, neuroimaging reveals that the cingulate cortex fires up when unpleasantness is felt from social distress or from physical pain that are experimentally induced. This finding led recently to the pain overlap theory,which proposes that physical pain and social pain share a common phenomenological and neural basis.

According to David Pearce’s Hedonistic Imperative, suffering is the result of Darwinian genetic design, and it can be abolished. BLTC Research and the Abolitionist Society promote replacing the pain/pleasure axis through genetic engineering and other scientific advances.

Footnotes

- ↑ More examples of physical suffering: pain, nausea, shortness of breath, weakness, dryness, various feelings of sickness, certain kinds of itching, tickling, tingling, numbness[1][2].

- ↑ More examples of mental suffering: grief, depression or sadness, disgust, irritation, anger, rage, hate, contempt, jealousy, envy, craving or yearning, frustration, heartbreak, anguish, anxiety, angst, fear, panic, horror, sense of injustice or righteous indignation, shame, guilt, remorse, regret, resentment, repentance, embarrassment, humiliation, boredom, apathy, confusion, disappointment, despair or hopelessness, doubt, emptiness, homesickness, loneliness, rejection, pity, self-pity...

- ↑ See, Dark Night of the Soul by St. John of the Cross ; translated and edited, with an introduction, by E. Allison Peers ; from the critical edition of P. Silverio de Santa Teresa. New York : Image Books/Doubleday, 1990. ISBN 0585035660

- ↑ Ralph G.H. Siu, Panetics − The Study of the Infliction of Suffering, Journal of Humanistic Psychology, Vol. 28 No. 3, Summer 1988.

- ↑ American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons http://www5.aaos.org/oko/vb/online_pubs/professional_liability/glossary.cfm Retrieved March 4, 2007.

Bibliography

- Cassell, Eric J.. 2002. The Nature of Suffering: And the Goals of Medicine. New York: New York: Oxford. Revised. ISBN 0195156161

- Wilkinson, Iain. 2005. Suffering : a sociological introduction. Cambridge, UK: Polity. ISBN 0745631967

- Kollar, Nathan. (1993) "Spiritualities of Suffering and Grief" in Death and Spirituality. K. Doka and J. Morgan eds. Baywood. ISBN 089503106X

- Kushner, Harold S. 2004. When Bad Things Happen to Good People. New York: New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell. Reprint. ISBN 0805241930

- Matlins, Stuart M. & Magida, Arthur J. 2006. How to Be a Perfect Stranger: A Guide to Other People’s Religious Ceremonies. 6th ed. Woodstock, VT Skylight Paths Publishing. ISBN 1594731403

- Yancey, Philip. 2007. Where is God When It Hurts?: A Comforting, Healing Guide for Coping with Hard Times. Grand Rapids: Michigan, Zondervan. ISBN 0310354102

- Lewis, C. S.. 2001. The Problem of Pain. HarperSanFrancisco; New Ed edition. ISBN 0060652969

- Graham, Billy. 1981. Till Armageddon : a perspective on suffering. Waco, Tex: Word Books. ISBN 0849901952

- Escalante Gonzalbo, Fernando. 2006. In the eyes of God : a study on the culture of suffering. LLILAS Translations from Latin America series. Austin: University of Texas Press, Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies. ISBN 0292713401

- Bowker, John. 1970. Problems of Suffering in Religions of the World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521074126

External links

- Pope John Paul II. 1984. http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/apost_letters/documents/hf_jp-ii_apl_11021984_salvifici-doloris_en.html Libreria Editrice Vaticana. On the Christian Meaning of Human Suffering. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- Ham, Ken and Sarafati, Dr Jonathan. http://www.answersingenesis.org/docs2002/death_suffering.asp Why is there death and suffering? AnswersinGenesis.org. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- Braybrooke, Marcus. 2002. http://www.religion-online.org/showchapter.asp?title=3269&C=2703 Religion-online.org. What can We Learn from Islam: The Struggle for True Religion. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- Leventry, Ellen. 2007. http://www.beliefnet.com/story/158/story_15870_1.html Beliefnet. Why Bad Things Happen:How different religions view the reasons for undeserved human suffering. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- Pearce, David, et al. 2002. http://www.abolitionist-society.com Abolitionist Society: Towards the Abolition of Suffering through Science. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- BLTC Research. 1995. http://www.gradients.com Life in the Far North:An information-theoretic perspective on Heaven. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- New York University. 2007. http://litmed.med.nyu.edu/Keyword?action=listann&id=54 Literature, Arts and Medicine database. Suffering. Retrieved March 4, 2007.

- International Society for Panethics. http://www.panetics.info. Retrieved March 4, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.