Difference between revisions of "Plesiosaur" - New World Encyclopedia

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

m (Remove * from 'optional' links) |

||

| (18 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{copyedited}} | ||

| + | |||

{{Taxobox_begin | color = pink | name = Plesiosaur}}<br/>{{StatusFossil}} | {{Taxobox_begin | color = pink | name = Plesiosaur}}<br/>{{StatusFossil}} | ||

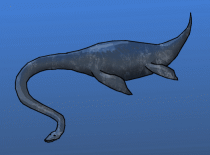

{{Taxobox_image | image = [[Image:Plesiosaur-illustration.png]]|caption =Plesiosaur illustration|}} | {{Taxobox_image | image = [[Image:Plesiosaur-illustration.png]]|caption =Plesiosaur illustration|}} | ||

| Line 6: | Line 8: | ||

{{Taxobox_phylum_entry | taxon = [[Chordate|Chordata]]}} | {{Taxobox_phylum_entry | taxon = [[Chordate|Chordata]]}} | ||

{{Taxobox_classis_entry | taxon = [[Reptile|Reptilia]]}} | {{Taxobox_classis_entry | taxon = [[Reptile|Reptilia]]}} | ||

| − | {{Taxobox_superordo_entry | taxon = [[Sauropterygia]] | + | {{Taxobox_superordo_entry | taxon = [[Sauropterygia]]}} |

| − | {{Taxobox_ordo_entry | taxon = '''Plesiosauria''' | + | {{Taxobox_ordo_entry | taxon = '''Plesiosauria'''}}<br/>{{Taxobox_authority | author = [[Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville|de Blainville]] | date = 1835}} |

{{Taxobox_end_placement}} | {{Taxobox_end_placement}} | ||

{{Taxobox_section_subdivision | color = pink | plural_taxon = Suborders}} | {{Taxobox_section_subdivision | color = pink | plural_taxon = Suborders}} | ||

| − | + | '''Plesiosauroidea''' <br /> | |

| − | + | '''Pliosauroidea''' | |

{{Taxobox_end}} | {{Taxobox_end}} | ||

| + | '''Plesiosaurs''' (Greek: ''plesios'' meaning "near" or "close to" and ''sauros'' meaning "lizard") were carnivorous, aquatic (mostly marine) [[reptile]]s that lived from the [[Triassic]] to the [[Cretaceous]] periods. They were the largest aquatic animals of their time. | ||

| − | ''' | + | The common name "plesiosaur" is variously applied both to the "true" plesiosaurs, belonging to the Suborder ''Plesiosauroidea,'' and to the larger [[taxonomy|taxonomic]] rank, the Order ''Plesiosauria.'' The Order Plesiosauria is divided into two suborders, Plesiosauroidea, made up (mostly) of long-necked forms, and Pliosauroidea, consisting of short-necked, elongated-headed forms. Plesiosaurs that belong to the suborder Pliosauroidea are more properly called "[[pliosaur]]s." |

| − | + | In this article, the term "plesiosaur" will refer to the order, while "true plesiosaur" and "pliosaur" will be used to designate organisms belonging to the suborders. | |

| − | True plesiosaurs" (''sensu'' Plesiosauroidea) first appeared at the very start of the [[Jurassic]] period, while the Order Plesiosauria appeared earlier, in the Middle [[Triassic]]. Plesiosaurs (including pliosaurs) thrived until the [[mass extinction#Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event|K-T extinction]], at the end of the [[Cretaceous]] period. Plesiosaurs were [[Mesozoic]] reptiles that lived at the same time as dinosaurs, | + | "True plesiosaurs" (''sensu'' Plesiosauroidea) first appeared at the very start of the [[Jurassic]] period, while the Order Plesiosauria appeared earlier, in the Middle [[Triassic]]. Plesiosaurs (including pliosaurs) thrived until the [[mass extinction#Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event|K-T extinction]], at the end of the [[Cretaceous]] period. Plesiosaurs were [[Mesozoic]] reptiles that lived at the same time as dinosaurs, and though they are often lumped together with the "terrible lizards," they were not [[dinosaur]]s. |

| − | There were many species of plesiosaurs and not all of them were as large as ''Liopleurodon'' | + | Although plesiosaurs are not considered to have direct, living descendants, they live today in the human imagination, in books, [[film]]s, and even as the source of the fabled "[[Loch Ness Monster]]." |

| + | |||

| + | There were many species of plesiosaurs and not all of them were as large as ''Liopleurodon,'' ''Kronosaurus,'' or ''Elasmosaurus.'' | ||

{{Mesozoic Footer}} | {{Mesozoic Footer}} | ||

| − | ==Description | + | ==Description== |

| − | [[Image:Plesiosaur anning.gif|thumb|left|220px|The first plesiosaur fossil, discovered by | + | [[Image:Plesiosaur anning.gif|thumb|left|220px|The first plesiosaur fossil, discovered by Mary Anning, 1821]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | When discovered, plesiosaur [[fossil]]s, were somewhat fancifully said to have resembled [http://www.oceansofkansas.com/Snaketurtle.html "a snake threaded through the shell of a turtle"]. | |

| − | + | Major types of plesiosaur are primarily distinguished by head and neck size. The Plesiosauroidea, such as Cryptoclididae, Elasmosauridae, and Plesiosauridae had long necks and may have been bottom-feeders, in shallow waters. The neck of ''Elasmosaurus'' was very long, twice the length of the body. The Pliosauridae (pliosaurs) had a short neck with large, elongated head and may have been at home in deeper waters. However, in recent classifications, one short-necked and large-headed [[Cretaceous]] group, the Polycotylidae, are included under the Plesiosauroidea, rather than under the traditional Pliosauroidea. | |

| − | + | The typical plesiosaur had a broad body and a short [[tail]]. They retained their ancestral two pairs of limbs, which evolved into large flippers. Plesiosaurs are considered to have evolved from the earlier [[nothosaur]]s, which had a more crocodile-like body. | |

| − | + | All plesiosaurs had four paddle-shaped flipper limbs. This is an unusual arrangement in aquatic animals and it is thought that they were used to propel the animal through the water by a combination of rowing movements and up-and-down movements. They had no tail fin and the tail was most likely used for helping in directional control. This arrangement is in contrast to that of the later [[mosasaur]]s and the earlier [[ichthyosaur]]s. There may be similarities with the method of swimming used by penguins and [[turtle]]s, which respectively have two and four flipper-like limbs. | |

| + | As a group, the plesiosaurs were the largest aquatic animals of their time, and even the smallest were about two meters (6.5 feet) long. They grew to be considerably larger than the largest giant [[crocodile]]s, and were bigger than their successors, the mosasaurs. However, their predecessors as rulers of the sea, the [[dolphin]]-like ichthyosaurs, are known to have reached 23 m in length, and the modern whale [[shark]] (18 m), sperm [[whale]] (20 m), and especially the blue [[whale]] (30 m) have produced considerably larger specimens. | ||

| − | + | The anteriorly placed internal nostrils have palatal grooves to channel water, the flow of which would be maintained by hydrodynamic pressure over the posteriorly placed external nares during locomotion. During its passage through the nasal ducts, the water would have been "tasted" by olfactory epithelia. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | "True plesiosaurs" appeared to have evolved from earlier, similar forms such as pistosaurs or very early, longer-necked pliosaurs. There are a number of families of true plesiosaurs, which retain the same general appearance and are distinguished by various specific details. These include the Plesiosauridae, unspecialized types which are limited to the Early [[Jurassic]] period; Cryptoclididae, (e.g. ''Cryptoclidus''), with a medium-long neck and somewhat stocky build; Elasmosauridae, with very long, inflexible necks and tiny heads; and the Cimoliasauridae, a poorly known group of small [[Cretaceous]] forms. | |

| − | == | + | == Behavior== |

| − | Plesiosaurs have been discovered with [[fossil]]s of | + | Plesiosaurs have been discovered with [[fossil]]s of belemnites ([[squid]]-like animals), and [[ammonite]]s (giant nautilus-like [[mollusk]]s) associated with their stomachs. They had powerful jaws, probably strong enough to bite through the hard shells of their prey. The bony fish (Osteichthyes), flourished in the Jurassic, and were likely prey as well. Recent evidence seems to indicate that some plesiosaurs may have, in fact, been bottom feeders.<ref>BBC News. [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/4341204.stm Plesiosaur bottom feeding shown.] Retrieved May 24, 2007.</ref> |

| − | + | Skeletons of plesiosaurs have also been discovered with [[gastrolith]]s in their stomachs, though whether to help break down food in a muscular gizzard, or to help with buoyancy has not been established (Everhart 2000). | |

| − | + | It had once been theorized that smaller plesiosaurs may have crawled up on a beach to lay their eggs, like the modern leatherback [[turtle]], but it is now widely held that plesiosaurs gave birth to live young. | |

| − | + | [[Image:Plesiosaur paddle c.jpg|thumb|right|Plesiosaur paddle in the Charmouth Heritage Coast Centre.]] | |

| − | [[Image:Plesiosaur paddle c.jpg|thumb|right|Plesiosaur paddle in the | + | Another curiosity is their four-flippered design. No modern animals have this swimming adaptation, so there is considerable speculation about what kind of stroke they used. The short-necked pliosaurs (e.g. ''Liopleurodon'') may have been fast swimmers. However, unlike their pliosaurian cousins, the long-necked true plesiosaurs (with the exception of the Polycotylidae) were built more for maneuverability than for speed, and were probably relatively slow swimmers. It is likely that they cruised slowly below the surface of the water, using their long flexible neck to move their head into position to snap up unwary fish or [[cephalopod]]s. Their unique, four-flippered swimming adaptation may have given them exceptional maneuverability, so that they could swiftly rotate their bodies as an aid to catching their prey. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Contrary to many reconstructions of true plesiosaurs, it would have been impossible for them to lift their head and long neck above the surface, in the "swan-like" pose that is often shown. Even if they had been able to bend their necks upward, to that degree (and they could not), gravity would have tipped their body forward and kept most of the heavy neck in the water. In 2006, Leslie Noè of the Sedgwick Museum in Cambridge, UK, announced research on fossilized vertebrae of a Muraenosaurus, concluding that the neck evolved to point downward, allowing the plesiosaur to feed on soft-shelled animals living on the sea floor. <ref>New Scientist. [http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg19225764.900-why-the-loch-ness-monster-is-no-plesiosaur.html Why the Loch Ness Monster is no Plesiosaur.] Retrieved May 24, 2007.</ref> | ||

==Taxonomy== | ==Taxonomy== | ||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

** '''Order PLESIOSAURIA''' | ** '''Order PLESIOSAURIA''' | ||

*** Suborder '''[[Pliosaur]]oidea''' (pliosaurs) | *** Suborder '''[[Pliosaur]]oidea''' (pliosaurs) | ||

| − | **** '' | + | **** ''Thalassiodracon'' |

| − | **** '' | + | **** ''Attenborosaurus'' |

| − | **** '' | + | **** ''Eurycleidus'' |

| − | **** Family | + | **** Family Rhomaleosauridae |

| − | **** Family | + | **** Family Pliosauridae |

*** Suborder '''[[Plesiosaur]]oidea''' (true plesiosaurs) | *** Suborder '''[[Plesiosaur]]oidea''' (true plesiosaurs) | ||

| − | **** Family | + | **** Family Plesiosauridae |

| − | **** (Unranked) ''' | + | **** (Unranked) '''Euplesiosauria''' |

| − | ***** Family | + | ***** Family Elasmosauridae |

***** Superfamily Cryptoclidoidea | ***** Superfamily Cryptoclidoidea | ||

| − | ****** Family | + | ****** Family Cryptoclididae |

| − | ****** (Unranked) | + | ****** (Unranked) Tricleidia |

| − | ******* '' | + | ******* ''Tricleidus'' |

| − | ******* Family | + | ******* Family Cimoliasauridae |

| − | ******* Family | + | ******* Family Polycotylidae (= "Dolichorhynchopidae") |

==Discovery== | ==Discovery== | ||

| − | The first plesiosaur skeletons were found in England by | + | The first plesiosaur skeletons were found in England by Mary Anning, in the early 1800s, and were among the first [[fossil]] [[vertebrate]]s to be described by science. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Many plesiosaur fossils have since been found, some of them virtually complete, and new discoveries are made frequently. One of the finest specimens was found in 2002 on the coast of Somerset in the United Kingdom by someone fishing from the shore. Another, less complete skeleton was found in 2002, in the cliffs at Filey, Yorkshire, England, by an amateur paleontologist. | |

| − | + | Many museums all over the world contain plesiosaur specimens. Notable among them is the collection of plesiosaurs in the Natural History Museum of London. Several historically important specimens can be found there, including the partial skeleton from Nottinghamshire reported by Stukely in 1719, which is the earliest written record of any marine reptile. | |

| − | The [[ | + | == Plesiosaurs and humans == |

| + | The plesiosaur has a popular place in the human imaginatin. Plesiosaurs are featured in many children's books, fiction (such as [[Jules Verne]]'s novel, ''[[Journey to the Center of the Earth]]''), and films, sometimes serving as a [[symbol]] of a lost, child-like sense of wonder. | ||

| − | + | Lake or sea monster sightings are occasionally explained as plesiosaurs. While the survival of a small, unrecorded breeding colony of plesiosaurs for the 65 million years since their apparent [[extinction]] is not seriously considered by scientists, the discovery of real and even more ancient living fossils such as the ''[[Coelacanth]],'' and of previously unknown but enormous deep-sea animals such as the giant squid, have fueled imaginations. | |

| − | + | The 1977 discovery of a carcass with flippers and what appeared to be a long neck and head, by the [[Japan]]ese [[fishing]] trawler ''Zuiyo Maru,'' off New Zealand, created a plesiosaur craze in Japan. Members of a blue-ribbon panel of eminent marine scientists in Japan reviewed the discovery. Professor Yoshinori Imaizumi, of the Japanese National Science Museum, said, "It's not a fish, whale, or any other mammal." However, the general consensus amongst scientists today is that it was a decayed basking shark.<ref>Kuban, Glen J. [http://paleo.cc/paluxy/plesios.htm Sea-monster or Shark?] Retrieved May 24, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | + | The [[Loch Ness Monster]] is reported to resemble a plesiosaur. Arguments against the plesiosaur theory include the fact that the lake is too cold for a [[cold-blooded]] animal to survive easily, that air-breathing animals like plesiosaurs would be easily spotted when they surface to breathe, that the lake is too small to support a breeding colony. and that the loch itself formed only 10,000 years ago during the last ice age. The famous "Surgeon's Photo" of the Loch Ness Monster was explained in November 1993, when Christian Spurling confessed on his deathbed that he made it from a toy submarine and putty. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The National Museums of Scotland confirmed that vertebrae discovered on the shores of Loch Ness, in 2003, belong to a plesiosaur, although there are some questions about whether the [[fossil]]s were planted (BBC News, July 16, 2003). It was reported in ''The Star'' (Malaysia) on April 8th, 2006, that fishermen discovered bones resembling that of a Plesiosaur near Sabah, [[Malaysia]]. The creature was speculated to have died only a month before. A team of researchers from University of Malaysia Sabah investigated the specimen but the bones were later determined to be those of a whale. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==Notes== | ||

| + | <references/> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | *Carpenter, K. 1996. A review of short-necked plesiosaurs from the Cretaceous of the western interior, North America. Neues Jahrbuch fuer Geologie und Palaeontologie Abhandlungen (Stuttgart) 201(2):259-287. | + | * Carpenter, K. 1996. A review of short-necked plesiosaurs from the Cretaceous of the western interior, North America. ''Neues Jahrbuch fuer Geologie und Palaeontologie Abhandlungen'' (Stuttgart) 201(2): 259-287. |

| − | *Carpenter, K. 1997. Comparative cranial anatomy of two North American Cretaceous plesiosaurs. | + | * Carpenter, K. 1997. Comparative cranial anatomy of two North American Cretaceous plesiosaurs. In J. M. Calloway, and E. L. Nicholls, eds., ''Ancient Marine Reptiles''. San Diego: Academic Press. Pg. 91-216. |

| − | *Carpenter, K. 1999. Revision of North American elasmosaurs from the Cretaceous of the western interior. Paludicola 2(2):148-173. | + | * Carpenter, K. 1999. Revision of North American elasmosaurs from the Cretaceous of the western interior. ''Paludicola'' 2(2): 148-173. |

| − | *Cicimurri, D., and M. Everhart | + | * Cicimurri, D., and M. Everhart. 2001. An elasmosaur with stomach contents and gastroliths from the Pierre Shale (late Cretaceous) of Kansas. ''Trans. Kansas. Acad. Sci.'' 104: 129-143. |

| − | *Cope, E. D. 1868. Remarks on a new enaliosaurian, ''Elasmosaurus platyurus''. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 20:92-93. | + | * Cope, E. D. 1868. Remarks on a new enaliosaurian, ''Elasmosaurus platyurus''. ''Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia'' 20:92-93. |

| − | *Ellis, R. 2003 | + | * Ellis, R. 2003. ''Sea Dragons''. Kansas University Press. |

| − | *Everhart, M. J., 2000. Gastroliths associated with plesiosaur remains in the Sharon Springs Member of the Pierre Shale (Late Cretaceous), western Kansas. Kansas Acad. Sci. Trans. 103(1-2):58-69. | + | * Everhart, M. J., 2000. Gastroliths associated with plesiosaur remains in the Sharon Springs Member of the Pierre Shale (Late Cretaceous), western Kansas. ''Kansas Acad. Sci. Trans.'' 103(1-2):58-69. |

| − | *Everhart, M. J. 2002. Where the elasmosaurs | + | * Everhart, M. J. 2002. Where the elasmosaurs roam. ''Prehistoric Times'' 53: 24-27. |

| − | *Everhart, M. J. 2004. Plesiosaurs as the food of mosasaurs; new data on the stomach contents of a ''Tylosaurus proriger'' (Squamata; Mosasauridae) from the Niobrara Formation of western Kansas. The Mosasaur 7:41-46. | + | * Everhart, M. J. 2004. Plesiosaurs as the food of mosasaurs; new data on the stomach contents of a ''Tylosaurus proriger'' (Squamata; Mosasauridae) from the Niobrara Formation of western Kansas. ''The Mosasaur'' 7:41-46. |

| − | *Everhart, M. J. 2005. Bite marks on an elasmosaur (Sauropterygia; Plesiosauria) paddle from the Niobrara Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) as probable evidence of feeding by the lamniform shark, ''Cretoxyrhina mantelli''. PalArch, Vertebrate | + | * Everhart, M. J. 2005. Bite marks on an elasmosaur (Sauropterygia; Plesiosauria) paddle from the Niobrara Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) as probable evidence of feeding by the lamniform shark, ''Cretoxyrhina mantelli''. PalArch, ''Vertebrate Paleontology'' 2(2): 14-24. |

| − | *Everhart, M.J. 2005. | + | * Everhart, M. J. 2005. ''Oceans of Kansas: A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea''. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34547-2 |

| − | *Everhart, M.J. 2005. | + | * Everhart, M. J. 2005. Gastroliths associated with plesiosaur remains in the Sharon Springs Member (Late Cretaceous) of the Pierre Shale, Western Kansas" ''Kansas Acad. Sci. Trans.'' 103(1-2): 58-69. |

| − | *Hampe, O. | + | * Hampe, O. 1992. Ein groBwuchsiger Pliosauride (Reptilia: Plesiosauria) aus der Unterkreide (oberes Aptium) von Kolumbien. ''Courier Forsch.-Inst. Senckenberg'' 145: 1-32. |

| − | *Lingham-Soliar, T., | + | * Lingham-Soliar, T. 1995. Anatomy and functional morphology of the largest marine reptile known, ''Mosasaurus hoffmanni'' (Mosasauridae, Reptilia) from the Upper Cretaceous, Upper Maastrichtian of the Netherlands''. ''Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. Lond.'' 347: 155-180 |

| − | *O'Keefe, F. R. | + | * O'Keefe, F. R. 2001. A cladistic analysis and taxonomic revision of the Plesiosauria (Reptilia: Sauropterygia). ''Acta Zoologica Fennica'' 213: 1-63. |

| − | *Storrs, G. W. | + | * Storrs, G. W. 1999. An examination of Plesiosauria (Diapsida: Sauropterygia) from the Niobrara Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) of central North America. ''University of Kansas Paleontologcial Contributions'' (N.S.), No. 11. |

| − | *Welles, S. P. 1943. Elasmosaurid plesiosaurs with a description of the new material from California and Colorado. University of California Memoirs 13:125-254 | + | * Welles, S. P. 1943. Elasmosaurid plesiosaurs with a description of the new material from California and Colorado. ''University of California Memoirs'' 13:125-254. |

| − | *Welles, S. P. 1952. A review of the North American Cretaceous elasmosaurs. University of California Publications in Geological Science 29:46-144 | + | * Welles, S. P. 1952. A review of the North American Cretaceous elasmosaurs. ''University of California Publications in Geological Science'' 29:46-144. |

| − | *Welles, S. P. 1962. A new species of elasmosaur from the Aptian of Columbia and a review of | + | * Welles, S. P. 1962. A new species of elasmosaur from the Aptian of Columbia and a review of the Cretaceous plesiosaurs. ''University of California Publications in Geological Science'' 46. |

| − | the Cretaceous plesiosaurs. University of California Publications in Geological Science 46 | + | * White, T. 1935. On the skull of ''Kronosaurus queenslandicus'' Longman. ''Occasional Papers Boston Soc. Nat. Hist.'' 8: 219-228 |

| − | *White, T. | + | * Williston, S. W. 1890. A new plesiosaur from the Niobrara Cretaceous of Kansas. ''Kansas Academy of Science Transactions'' 12:174-178. |

| − | *Williston, S. W. 1890. A new plesiosaur from the Niobrara Cretaceous of Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science | + | * Williston, S. W. 1902. Restoration of ''Dolichorhynchops osborni'', a new Cretaceous plesiosaur. ''Kansas University Science Bulletin'' 1(9):241-244. |

| − | *Williston, S. W. 1902. Restoration of ''Dolichorhynchops osborni'', a new Cretaceous plesiosaur. Kansas University Science Bulletin | + | * Williston, S. W. 1903. North American plesiosaurs. ''Field Columbian Museum, Publication 73, Geology Series'' 2(1): 1-79. |

| − | *Williston, S. W. 1903. North American plesiosaurs. Field Columbian Museum, Publication 73, Geology Series 2(1): 1-79 | + | * Williston, S. W. 1906. North American plesiosaurs: ''Elasmosaurus'', ''Cimoliasaurus'', and ''Polycotylus''. ''American Journal of Science'', Series 4, 21(123): 221-234. |

| − | *Williston, S. W. 1906. North American plesiosaurs: ''Elasmosaurus'', ''Cimoliasaurus'', and ''Polycotylus''. American Journal of Science, Series 4, 21(123): 221-234 | + | * Williston, S. W. 1908. North American plesiosaurs: ''Trinacromerum''. ''Journal of Geology'' 16: 715-735. |

| − | *Williston, S. W. 1908. North American plesiosaurs: ''Trinacromerum''. Journal of Geology 16: 715-735 | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{credit2|Plesiosaur|94843554|Plesiosauria|93261268}} | {{credit2|Plesiosaur|94843554|Plesiosauria|93261268}} | ||

[[Category:Life sciences]] | [[Category:Life sciences]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Animals]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Reptiles]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Paleontology]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Evolution]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:15, 29 August 2008

| Plesiosaur Conservation status: Fossil | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Plesiosaur illustration | ||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Suborders | ||||||||||

|

Plesiosauroidea |

Plesiosaurs (Greek: plesios meaning "near" or "close to" and sauros meaning "lizard") were carnivorous, aquatic (mostly marine) reptiles that lived from the Triassic to the Cretaceous periods. They were the largest aquatic animals of their time.

The common name "plesiosaur" is variously applied both to the "true" plesiosaurs, belonging to the Suborder Plesiosauroidea, and to the larger taxonomic rank, the Order Plesiosauria. The Order Plesiosauria is divided into two suborders, Plesiosauroidea, made up (mostly) of long-necked forms, and Pliosauroidea, consisting of short-necked, elongated-headed forms. Plesiosaurs that belong to the suborder Pliosauroidea are more properly called "pliosaurs."

In this article, the term "plesiosaur" will refer to the order, while "true plesiosaur" and "pliosaur" will be used to designate organisms belonging to the suborders.

"True plesiosaurs" (sensu Plesiosauroidea) first appeared at the very start of the Jurassic period, while the Order Plesiosauria appeared earlier, in the Middle Triassic. Plesiosaurs (including pliosaurs) thrived until the K-T extinction, at the end of the Cretaceous period. Plesiosaurs were Mesozoic reptiles that lived at the same time as dinosaurs, and though they are often lumped together with the "terrible lizards," they were not dinosaurs.

Although plesiosaurs are not considered to have direct, living descendants, they live today in the human imagination, in books, films, and even as the source of the fabled "Loch Ness Monster."

There were many species of plesiosaurs and not all of them were as large as Liopleurodon, Kronosaurus, or Elasmosaurus.

| Mesozoic era (251 - 65 mya) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Triassic | Jurassic | Cretaceous |

Description

When discovered, plesiosaur fossils, were somewhat fancifully said to have resembled "a snake threaded through the shell of a turtle".

Major types of plesiosaur are primarily distinguished by head and neck size. The Plesiosauroidea, such as Cryptoclididae, Elasmosauridae, and Plesiosauridae had long necks and may have been bottom-feeders, in shallow waters. The neck of Elasmosaurus was very long, twice the length of the body. The Pliosauridae (pliosaurs) had a short neck with large, elongated head and may have been at home in deeper waters. However, in recent classifications, one short-necked and large-headed Cretaceous group, the Polycotylidae, are included under the Plesiosauroidea, rather than under the traditional Pliosauroidea.

The typical plesiosaur had a broad body and a short tail. They retained their ancestral two pairs of limbs, which evolved into large flippers. Plesiosaurs are considered to have evolved from the earlier nothosaurs, which had a more crocodile-like body.

All plesiosaurs had four paddle-shaped flipper limbs. This is an unusual arrangement in aquatic animals and it is thought that they were used to propel the animal through the water by a combination of rowing movements and up-and-down movements. They had no tail fin and the tail was most likely used for helping in directional control. This arrangement is in contrast to that of the later mosasaurs and the earlier ichthyosaurs. There may be similarities with the method of swimming used by penguins and turtles, which respectively have two and four flipper-like limbs.

As a group, the plesiosaurs were the largest aquatic animals of their time, and even the smallest were about two meters (6.5 feet) long. They grew to be considerably larger than the largest giant crocodiles, and were bigger than their successors, the mosasaurs. However, their predecessors as rulers of the sea, the dolphin-like ichthyosaurs, are known to have reached 23 m in length, and the modern whale shark (18 m), sperm whale (20 m), and especially the blue whale (30 m) have produced considerably larger specimens.

The anteriorly placed internal nostrils have palatal grooves to channel water, the flow of which would be maintained by hydrodynamic pressure over the posteriorly placed external nares during locomotion. During its passage through the nasal ducts, the water would have been "tasted" by olfactory epithelia.

"True plesiosaurs" appeared to have evolved from earlier, similar forms such as pistosaurs or very early, longer-necked pliosaurs. There are a number of families of true plesiosaurs, which retain the same general appearance and are distinguished by various specific details. These include the Plesiosauridae, unspecialized types which are limited to the Early Jurassic period; Cryptoclididae, (e.g. Cryptoclidus), with a medium-long neck and somewhat stocky build; Elasmosauridae, with very long, inflexible necks and tiny heads; and the Cimoliasauridae, a poorly known group of small Cretaceous forms.

Behavior

Plesiosaurs have been discovered with fossils of belemnites (squid-like animals), and ammonites (giant nautilus-like mollusks) associated with their stomachs. They had powerful jaws, probably strong enough to bite through the hard shells of their prey. The bony fish (Osteichthyes), flourished in the Jurassic, and were likely prey as well. Recent evidence seems to indicate that some plesiosaurs may have, in fact, been bottom feeders.[1]

Skeletons of plesiosaurs have also been discovered with gastroliths in their stomachs, though whether to help break down food in a muscular gizzard, or to help with buoyancy has not been established (Everhart 2000).

It had once been theorized that smaller plesiosaurs may have crawled up on a beach to lay their eggs, like the modern leatherback turtle, but it is now widely held that plesiosaurs gave birth to live young.

Another curiosity is their four-flippered design. No modern animals have this swimming adaptation, so there is considerable speculation about what kind of stroke they used. The short-necked pliosaurs (e.g. Liopleurodon) may have been fast swimmers. However, unlike their pliosaurian cousins, the long-necked true plesiosaurs (with the exception of the Polycotylidae) were built more for maneuverability than for speed, and were probably relatively slow swimmers. It is likely that they cruised slowly below the surface of the water, using their long flexible neck to move their head into position to snap up unwary fish or cephalopods. Their unique, four-flippered swimming adaptation may have given them exceptional maneuverability, so that they could swiftly rotate their bodies as an aid to catching their prey.

Contrary to many reconstructions of true plesiosaurs, it would have been impossible for them to lift their head and long neck above the surface, in the "swan-like" pose that is often shown. Even if they had been able to bend their necks upward, to that degree (and they could not), gravity would have tipped their body forward and kept most of the heavy neck in the water. In 2006, Leslie Noè of the Sedgwick Museum in Cambridge, UK, announced research on fossilized vertebrae of a Muraenosaurus, concluding that the neck evolved to point downward, allowing the plesiosaur to feed on soft-shelled animals living on the sea floor. [2]

Taxonomy

The classification of the Plesiosauria has varied over time; the following represents one current version (mostly following O'Keefe 2001)

- Superorder SAUROPTERYGIA

- Order PLESIOSAURIA

- Suborder Pliosauroidea (pliosaurs)

- Thalassiodracon

- Attenborosaurus

- Eurycleidus

- Family Rhomaleosauridae

- Family Pliosauridae

- Suborder Plesiosauroidea (true plesiosaurs)

- Family Plesiosauridae

- (Unranked) Euplesiosauria

- Family Elasmosauridae

- Superfamily Cryptoclidoidea

- Family Cryptoclididae

- (Unranked) Tricleidia

- Tricleidus

- Family Cimoliasauridae

- Family Polycotylidae (= "Dolichorhynchopidae")

- Suborder Pliosauroidea (pliosaurs)

- Order PLESIOSAURIA

Discovery

The first plesiosaur skeletons were found in England by Mary Anning, in the early 1800s, and were among the first fossil vertebrates to be described by science.

Many plesiosaur fossils have since been found, some of them virtually complete, and new discoveries are made frequently. One of the finest specimens was found in 2002 on the coast of Somerset in the United Kingdom by someone fishing from the shore. Another, less complete skeleton was found in 2002, in the cliffs at Filey, Yorkshire, England, by an amateur paleontologist.

Many museums all over the world contain plesiosaur specimens. Notable among them is the collection of plesiosaurs in the Natural History Museum of London. Several historically important specimens can be found there, including the partial skeleton from Nottinghamshire reported by Stukely in 1719, which is the earliest written record of any marine reptile.

Plesiosaurs and humans

The plesiosaur has a popular place in the human imaginatin. Plesiosaurs are featured in many children's books, fiction (such as Jules Verne's novel, Journey to the Center of the Earth), and films, sometimes serving as a symbol of a lost, child-like sense of wonder.

Lake or sea monster sightings are occasionally explained as plesiosaurs. While the survival of a small, unrecorded breeding colony of plesiosaurs for the 65 million years since their apparent extinction is not seriously considered by scientists, the discovery of real and even more ancient living fossils such as the Coelacanth, and of previously unknown but enormous deep-sea animals such as the giant squid, have fueled imaginations.

The 1977 discovery of a carcass with flippers and what appeared to be a long neck and head, by the Japanese fishing trawler Zuiyo Maru, off New Zealand, created a plesiosaur craze in Japan. Members of a blue-ribbon panel of eminent marine scientists in Japan reviewed the discovery. Professor Yoshinori Imaizumi, of the Japanese National Science Museum, said, "It's not a fish, whale, or any other mammal." However, the general consensus amongst scientists today is that it was a decayed basking shark.[3]

The Loch Ness Monster is reported to resemble a plesiosaur. Arguments against the plesiosaur theory include the fact that the lake is too cold for a cold-blooded animal to survive easily, that air-breathing animals like plesiosaurs would be easily spotted when they surface to breathe, that the lake is too small to support a breeding colony. and that the loch itself formed only 10,000 years ago during the last ice age. The famous "Surgeon's Photo" of the Loch Ness Monster was explained in November 1993, when Christian Spurling confessed on his deathbed that he made it from a toy submarine and putty.

The National Museums of Scotland confirmed that vertebrae discovered on the shores of Loch Ness, in 2003, belong to a plesiosaur, although there are some questions about whether the fossils were planted (BBC News, July 16, 2003). It was reported in The Star (Malaysia) on April 8th, 2006, that fishermen discovered bones resembling that of a Plesiosaur near Sabah, Malaysia. The creature was speculated to have died only a month before. A team of researchers from University of Malaysia Sabah investigated the specimen but the bones were later determined to be those of a whale.

Notes

- ↑ BBC News. Plesiosaur bottom feeding shown. Retrieved May 24, 2007.

- ↑ New Scientist. Why the Loch Ness Monster is no Plesiosaur. Retrieved May 24, 2007.

- ↑ Kuban, Glen J. Sea-monster or Shark? Retrieved May 24, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carpenter, K. 1996. A review of short-necked plesiosaurs from the Cretaceous of the western interior, North America. Neues Jahrbuch fuer Geologie und Palaeontologie Abhandlungen (Stuttgart) 201(2): 259-287.

- Carpenter, K. 1997. Comparative cranial anatomy of two North American Cretaceous plesiosaurs. In J. M. Calloway, and E. L. Nicholls, eds., Ancient Marine Reptiles. San Diego: Academic Press. Pg. 91-216.

- Carpenter, K. 1999. Revision of North American elasmosaurs from the Cretaceous of the western interior. Paludicola 2(2): 148-173.

- Cicimurri, D., and M. Everhart. 2001. An elasmosaur with stomach contents and gastroliths from the Pierre Shale (late Cretaceous) of Kansas. Trans. Kansas. Acad. Sci. 104: 129-143.

- Cope, E. D. 1868. Remarks on a new enaliosaurian, Elasmosaurus platyurus. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 20:92-93.

- Ellis, R. 2003. Sea Dragons. Kansas University Press.

- Everhart, M. J., 2000. Gastroliths associated with plesiosaur remains in the Sharon Springs Member of the Pierre Shale (Late Cretaceous), western Kansas. Kansas Acad. Sci. Trans. 103(1-2):58-69.

- Everhart, M. J. 2002. Where the elasmosaurs roam. Prehistoric Times 53: 24-27.

- Everhart, M. J. 2004. Plesiosaurs as the food of mosasaurs; new data on the stomach contents of a Tylosaurus proriger (Squamata; Mosasauridae) from the Niobrara Formation of western Kansas. The Mosasaur 7:41-46.

- Everhart, M. J. 2005. Bite marks on an elasmosaur (Sauropterygia; Plesiosauria) paddle from the Niobrara Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) as probable evidence of feeding by the lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli. PalArch, Vertebrate Paleontology 2(2): 14-24.

- Everhart, M. J. 2005. Oceans of Kansas: A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34547-2

- Everhart, M. J. 2005. Gastroliths associated with plesiosaur remains in the Sharon Springs Member (Late Cretaceous) of the Pierre Shale, Western Kansas" Kansas Acad. Sci. Trans. 103(1-2): 58-69.

- Hampe, O. 1992. Ein groBwuchsiger Pliosauride (Reptilia: Plesiosauria) aus der Unterkreide (oberes Aptium) von Kolumbien. Courier Forsch.-Inst. Senckenberg 145: 1-32.

- Lingham-Soliar, T. 1995. Anatomy and functional morphology of the largest marine reptile known, Mosasaurus hoffmanni (Mosasauridae, Reptilia) from the Upper Cretaceous, Upper Maastrichtian of the Netherlands. Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. Lond. 347: 155-180

- O'Keefe, F. R. 2001. A cladistic analysis and taxonomic revision of the Plesiosauria (Reptilia: Sauropterygia). Acta Zoologica Fennica 213: 1-63.

- Storrs, G. W. 1999. An examination of Plesiosauria (Diapsida: Sauropterygia) from the Niobrara Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) of central North America. University of Kansas Paleontologcial Contributions (N.S.), No. 11.

- Welles, S. P. 1943. Elasmosaurid plesiosaurs with a description of the new material from California and Colorado. University of California Memoirs 13:125-254.

- Welles, S. P. 1952. A review of the North American Cretaceous elasmosaurs. University of California Publications in Geological Science 29:46-144.

- Welles, S. P. 1962. A new species of elasmosaur from the Aptian of Columbia and a review of the Cretaceous plesiosaurs. University of California Publications in Geological Science 46.

- White, T. 1935. On the skull of Kronosaurus queenslandicus Longman. Occasional Papers Boston Soc. Nat. Hist. 8: 219-228

- Williston, S. W. 1890. A new plesiosaur from the Niobrara Cretaceous of Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science Transactions 12:174-178.

- Williston, S. W. 1902. Restoration of Dolichorhynchops osborni, a new Cretaceous plesiosaur. Kansas University Science Bulletin 1(9):241-244.

- Williston, S. W. 1903. North American plesiosaurs. Field Columbian Museum, Publication 73, Geology Series 2(1): 1-79.

- Williston, S. W. 1906. North American plesiosaurs: Elasmosaurus, Cimoliasaurus, and Polycotylus. American Journal of Science, Series 4, 21(123): 221-234.

- Williston, S. W. 1908. North American plesiosaurs: Trinacromerum. Journal of Geology 16: 715-735.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.