Ichthyosaur

| Ichthyosaurians

| ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

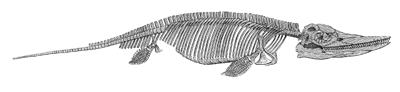

Ichthyosauria, Holzmaden, Museum Wiesbaden

| ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

|

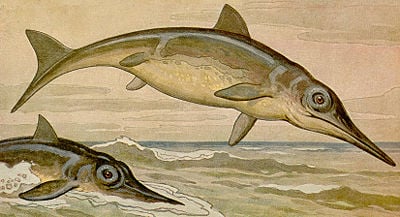

Ichthyosaurs (Greek for "fish lizard"—ιχθυς or ichthyos, meaning "fish" and σαυρος or sauros, meaning "lizard") were giant marine reptiles that resembled fish and dolphins, with an elongated, toothed snout like a crocodile. Ichthyosaurs, which lived during a large part of the Mesozoic era, were the dominant reptiles in the sea at about the same time dinosaurs ruled the land; they appeared about 250 million years ago (mya), slightly earlier than the dinosaurs (230 Mya), and disappeared about 90 mya, about 25 million years before the dinosaurs became extinct. The largest ichthyosaurs exceeded 15 meters (45 feet) in length (Motani 2000a).

Ichthyosaurus is the common name for reptiles belonging to the order known as Ichthyosauria or the subclass or superorder known as Ichthyopterygia ("fish flippers" or "fish paddles"). Ichthyopterygia is a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1840, recognizing their paddle-shaped fins or "flippers." The names Ichthyosauria and Ichthyopterygia until recently referred to the same group, but Ichthyosauria was named by Blainville in 1835 and thus has priority. Ichtyopterygia now is used more for the parent clade of the Ichthyosauria.

The finding of ichthyosaur fossils posed a problem for early eighteenth century scientists and religious adherents, who offered such explanations as their being traces of still existing, but undiscovered creatures or remnants of animals killed in the Great Flood. Today, it is recognized that ichthyosaurs represented one stage in the development of life on earth and disappeared millions of years ago. It is not conclusively known why they became extinct.

Ichthyosaurs are considered to have arisen from land reptiles that moved back into the water, in a development parallel to that of modern-day dolphins and whales. This would have happened in the middle Triassic period. Ichthyosaurs were particularly abundant in the Jurassic period, until they were replaced as the top aquatic predators by plesiosaurs in the Cretaceous Period.

| Mesozoic era (251 - 65 mya) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Triassic | Jurassic | Cretaceous |

Description

Early ichthyosaurs (really basal Ichthyopterygia, prior to true ichthyosaurs) were more slender and lizard like, and later forms (Ichthyosauria) were more fish shaped with a dorsal fin and tail fluke (Motani 2000a).

Ichthyosaurs averaged two to four meters in length, (although a few were smaller, and some species grew much larger). They had a porpoise-like head and a long, toothed snout.

The more advanced, fish-like ichthyosaurs apparently were built for speed, like modern tuna and mackerel; some appear also to have been deep divers, like some modern whales (Motani 2000a). It has been estimated that ichthyosaurs could swim at speeds up to 40 km/h (25 mph).

Similar to modern cetaceans such as whales and dolphins, ichthyosaurs were air-breathing and also considered to have been viviparous (giving live birth; some adult fossils have even been found containing fetuses). Although they were reptiles and descended from egg-laying ancestors, viviparity is not as unexpected as it first might seem. All air-breathing marine creatures must either come ashore to lay eggs, like turtles and some sea snakes, or else give birth to live young in surface waters, like whales and dolphins. Given their streamlined bodies, heavily adapted for fast swimming, it would have been difficult for ichthyosaurs to scramble successfully onto land to lay eggs.

According to weight estimates by Ryosuke Motani (2000b) a 2.4 meter (8 ft) Stenopterygius weighed around 163 to 168 kg (360 to 370 lb), while a 4.0 meter (13 ft) Ophthalmosaurus icenicus weighed 930 to 950 kg (about a ton).

Although ichthyosaurs looked like fish, they were not. Biologist Stephen Jay Gould said the ichthyosaur was his favorite example of convergent evolution, where similarities of structure are not from common ancestry:

converged so strongly on fishes that it actually evolved a dorsal fin and tail in just the right place and with just the right hydrological design. These structures are all the more remarkable because they evolved from nothing—the ancestral terrestrial reptile had no hump on its back or blade on its tail to serve as a precursor.

In fact, the earliest reconstructions of ichthyosaurs omitted the dorsal fin, which had no hard skeletal structure, until finely-preserved specimens recovered in the 1890s from the Holzmaden lagerstätten (sedimentary deposits with great fossil richness or completeness) in Germany revealed traces of the fin. Unique conditions permitted the preservation of soft tissue impressions.

Ichthyosaurs had fin-like limbs, which were possibly used for stabilization and directional control, rather than propulsion, which would have come from the large shark-like tail. The tail was bi-lobed, with the lower lobe being supported by the caudal vertebral column, which was "kinked" ventrally to follow the contours of the ventral lobe.

Apart from the obvious similarities to fish, the ichthyosaurs also shared parallel developmental features with marine mammals, particularly dolphins. This gave them a broadly similar appearance, possibly implied similar activity, and presumably placed them generally in a similar ecological niche.

For their food, many of the fish-shaped ichthyosaurs likely relied heavily on ancient cephalopod kin of squids called belemnites. Some early ichthyosaurs had teeth adapted for crushing shellfish. They also most likely fed on fish, and a few of the larger species had heavy jaws and teeth that indicated they fed on smaller reptiles. Ichthyosaurs ranged so widely in size, and survived for so long, that they are likely to have had a wide range of prey. Typical ichthyosaurs have very large eyes, protected within a bony ring, suggesting that they may have hunted at night.

History of discoveries

Ichthyosaurs had first been described in 1699 from fossil fragments discovered in Wales.

The first fossil vertebrae were published twice in 1708 as tangible mementos of the Universal Deluge (Great Flood). The first complete ichthyosaur fossil was found in 1811 by Mary Anning in Lyme Regis, along what is now called the Jurassic Coast. She subsequently discovered three separate species.

In 1905, the Saurian Expedition, led by John C. Merriam of the University of California and financed by Annie Alexander, found 25 specimens in central Nevada (United States), which during the Triassic was under a shallow ocean. Several of the specimens are now in the collection of the University of California Museum of Paleontology. Other specimens are embedded in the rock and visible at Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park in Nye County, Nevada. In 1977, the Triassic ichthyosaur Shonisaurus became the State Fossil of Nevada. Nevada is the only U.S. state to possess a complete skeleton, 55 ft (17 m) of this extinct marine reptile. In 1992, Canadian ichthyologist Dr. Elizabeth Nicholls (Curator of Marine Reptiles at the Royal Tyrrell {"tur ell"} Museum) uncovered the largest fossil specimen ever, a 23m (75ft) long example.

History

These earliest ichthyosaurs, looking more like finned lizards than the familiar fish or dolphin forms, are known from the Early and Early-Middle (Olenekian and Anisian) Triassic strata of Canada, China, Japan, and Spitsbergen in Norway. These primitive forms included the genera Chaohusaurus, Grippia, and Utatsusaurus.

These very early proto-ichthyosaurs are now classified as Ichthyopterygia rather than as ichthyosaurs proper (Motani 1997, Motani et al. 1998). They were mostly small (a meter or less in length) with elongate bodies and long, spool shaped vertebrae, indicating that they swam in a sinuous eel-like manner. This allowed for quick movements and maneuverability that were an advantage in shallow-water hunting (Motani 2000a). Even at this early stage they were already very specialized animals with proper flippers, and would have been incapable of movement on land.

These basal ichthyopterygians (prior to and ancestral to true Ichthyosauria) quickly gave rise to true ichthyosaurs sometime in the latest Early Triassic or earliest Middle Triassic. These latter diversified into a variety of forms, including the sea-serpent like Cymbospondylus, which reached 10 meters, and smaller more typical forms like Mixosaurus. By the Late Triassic, ichthyosaurs consisted of both classic Shastasauria and more advanced, "dolphin"-like Euichthyosauria (Californosaurus, Toretocnemus) and Parvipelvia (Hudsonelpidia, Macgowania). Experts disagree over whether these represent an evolutionary continuum, with the less specialized shastosaurs a paraphyletic grade that was evolving into the more advanced forms (Maisch and Matzke 2000), or whether the two were separate clades that evolved from a common ancestor earlier on (Nicholls and Manabe 2001).

During the Carnian (228.0–216.5 mya) and Norian (216.5–203.6 mya) of the Upper Triassic, shastosaurs reached huge sizes. Shonisaurus popularis, known from a number of specimens from the Carnian of Nevada, was 15 meters long. Norian shonisaurs are known from both sides of the Pacific. Himalayasaurus tibetensis and Tibetosaurus (probably a synonym) have been found in Tibet. These large (10 to 15 meters long) ichthyosaurs probably belong to the same genus as Shonisaurus (Motani et al. 1999, Lucas 2001).

The gigantic Shonisaurus sikanniensis, whose remains were found in the Pardonet formation of British Columbia, reached as much as 21 meters in length—the largest marine reptile known to date.

These giants (along with their smaller cousins) seemed to have disappeared at the end of the Norian. Rhaetian (latest Triassic) ichthyosaurs are known from England, and these are very similar to those of the Early Jurassic. Like the dinosaurs, the ichthyosaurs and their contemporaries, the plesiosaurs survived the end-Triassic extinction event, and immediately diversified to fill the vacant ecological niches of the earliest Jurassic.

The Early Jurassic, like the Late Triassic, saw ichthyosaurs flourish, which is represented by four families and a variety of species, ranging from one to ten meters in length. Genera include Eurhinosaurus, Ichthyosaurus, Leptonectes, Stenopterygius, and the large predator Temnodontosaurus, along with the persistently primitive Suevoleviathan, which was little changed from its Norian ancestors. All these animals had streamlined, dolphin-like forms, although the more primitive animals were perhaps more elongated than the advanced and compact Stenopterygius and Ichthyosaurus.

Ichthyosaurs were still common in the Middle Jurassic, but by then had decreased in diversity. All belonged to the single clade Ophthalmosauria. Represented by the 4 meter long Ophthalmosaurus and related genera, they were very similar to Ichthyosaurus, and had attained a perfect "tear-drop" streamlined form. The eyes of Ophthalmosaurus were huge, and it is likely that these animals hunted in dim and deep water (Motani 2000a).

Ichthyosaurs seemed to decrease in diversity even further with the Cretaceous. Only a single genus is known, Platypterygius, and although it had a worldwide distribution, there was little diversity species-wise. This last ichthyosaur genus fell victim to the mid-Cretaceous (Cenomanian-Turonian) extinction event (as did some of the giant pliosaurs), although ironically less hydrodynamically efficient animals like mosasaurs and long-necked plesiosaurs flourished. It seems that the ichthyosaurs became the victim of their own overspecialization and were unable to keep up with the fast swimming and highly evasive new teleost fishes, which were becoming dominant at this time and against which the sit-and-wait ambush strategies of the mosasaurs proved superior (Lingham-Soliar 1999).

Taxonomy of species

- Order ICHTHYOSAURIA

- Family Mixosauridae

- Suborder Merriamosauriformes

- Guanlingsaurus

- (unranked) Merriamosauria

- Family Shastasauridae

- Infraorder Euichthyosauria ("true ichthyosaurs")

- Family Teretocnemidae

- Californosaurus

- (Unranked) Parvipelvia ("small pelves")

- Macgovania

- Hudsonelpidia

- Suevoleviathan

- Temnodontosaurus

- Family Leptonectidae

- Infraorder Thunnosauria ("tuna lizards")

- Family Stenopterygiidae

- Family Ichthyosaurus

- Family Ophthalmosauridae

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ellis, R. 2003. Sea Dragons - Predators of the Prehistoric Oceans. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-1269-6

- Gould, S. J.. 1994. Bent out of shape. In S. J. Gould, Eight Little Piggies. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0393311392

- Lingham-Soliar, T. 1999. A functional analysis of the skull of Goronyosaurus nigeriensis (Squamata: Mosasauridae) and its bearing on the predatory behavior and evolution of the enigmatic taxon. N. Jb. Geol. Palaeont. Abh. 2134 (3): 355-74.

- Maisch, M. W., and A. T. Matzke. 2000. The ichthyosauria. Stuttgarter Beitraege zur Naturkunde. Serie B. Geologie und Palaeontologie 298: 1-159.

- McGowan, C. 1992. Dinosaurs, Spitfires and Sea Dragons. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-20770-X

- McGowan, C., and R. Motani. 2003. Ichthyopterygia. Handbook of Paleoherpetology, Part 8, Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil

- Motani, R. 1997. Temporal and spatial distribution of tooth implantation in ichthyosaurs. In J. M. Callaway and E. L. Nicholls (eds.), Ancient Marine Reptiles. Academic Press. pp. 81-103.

- Motani, R. 2000a. Rulers of the Jurassic seas. Scientific American 283(6):52-59.

- Motani, R. 2000b. Ichthyosaur weight. Berkely University. Retrieved April 2, 2014.

- Motani, R., Hailu, Y., and C. McGowan. 1996. Eel-like swimming in the earliest Ichthyosaurs. Nature 382: 347–348.

- Motani, R., N. Minoura, and T. Ando. 1998. Ichthyosaurian relationships illuminated by new primitive skeletons from Japan. Nature 393: 255-257.

- Motani, R., M. Manabe, and Z-M. Dong. 1999. The status of Himalayasaurus tibetensis (Ichthyopterygia). Paludicola 2(2):174-181.

- Motani, R., B. M. Rothschild, and W. Wahl. 1999. Nature 402: 747.

- Nicholls, E. L., and M. Manabe. 2001. A new genus of ichthyosaur from the Late Triassic Pardonet Formation of British Columbia: bridging the Triassic-Jurassic gap. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 38: 983-1002.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.