Difference between revisions of "Omaha (tribe)" - New World Encyclopedia

(→External links: Checked links, removed bad links, added Retrieved dates.) |

|||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

The Omaha tribe began as a larger woodland tribe comprising both the Omaha and [[Quapaw]] tribes. This original tribe inhabited the area near the [[Ohio River|Ohio]] and [[Wabash River|Wabash]] rivers around the year 1700. | The Omaha tribe began as a larger woodland tribe comprising both the Omaha and [[Quapaw]] tribes. This original tribe inhabited the area near the [[Ohio River|Ohio]] and [[Wabash River|Wabash]] rivers around the year 1700. | ||

| − | As the tribe migrated west it split into what became the Omaha tribe and the Quapaw tribe. The Quapaw settled in what is now [[Arkansas]] and the Omaha tribe, known as ''U-Mo'n-Ho'n'' ("Dwellers on the Bluff").<ref>John Joseph | + | As the tribe migrated west it split into what became the Omaha tribe and the Quapaw tribe. The Quapaw settled in what is now [[Arkansas]] and the Omaha tribe, known as ''U-Mo'n-Ho'n'' ("Dwellers on the Bluff").<ref>Mathews, John Joseph. 1961. ''The Osages: Children of the Middle Waters''. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.</ref> settled near the [[Missouri River]] in what is now northwestern [[Iowa]]. Conflict with the [[Sioux]] and the splitting off of part of the tribe into the Ponca, forced the Omaha tribe to retreat to an area around [[Bow Creek (Nebraska)|Bow Creek]] in northeastern Nebraska in 1775, settling near present day [[Homer, Nebraska]]. |

[[France|French]] [[Fur trapper|fur trappers]] found the Omaha on the eastern side of the Missouri River in the mid-1700s. The Omaha were believed to have ranged from the [[Cheyenne River]] in [[South Dakota]] to the [[Platte River]] in Nebraska. [[Lewis and Clark]] found the tribe on the western side of the Missouri south of present-day [[Sioux City, Iowa]] in 1804. | [[France|French]] [[Fur trapper|fur trappers]] found the Omaha on the eastern side of the Missouri River in the mid-1700s. The Omaha were believed to have ranged from the [[Cheyenne River]] in [[South Dakota]] to the [[Platte River]] in Nebraska. [[Lewis and Clark]] found the tribe on the western side of the Missouri south of present-day [[Sioux City, Iowa]] in 1804. | ||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

[[Image:Logan fontenelle.jpg|thumb|right|200 px|]] | [[Image:Logan fontenelle.jpg|thumb|right|200 px|]] | ||

| − | [[Logan Fontenelle]], also known as '''Shon-ga-ska''' or '''Chief White Horse''', (1825–July 16, 1855), was a [[mixed blood]] Omaha tribal leader who rose from obscurity to become chief. For several years, he also served as an interpreter for the United States government.<ref name=logan> | + | [[Logan Fontenelle]], also known as '''Shon-ga-ska''' or '''Chief White Horse''', (1825–July 16, 1855), was a [[mixed blood]] Omaha tribal leader who rose from obscurity to become chief. For several years, he also served as an interpreter for the United States government.<ref name=logan>[http://www.nde.state.ne.us/SS/notables/fontenelle.html Logan Fontenelle]. Nebraska Department of Education. Retrieved November 11, 2007.</ref> Fontenelle was present in August 1846 when the Omahas signed a treaty with [[Brigham Young]] allowing the [[Mormon]] pioneers to create [[Cutler's Park]] settlement on Omaha territorial lands.<ref>Boughter, Judith A. 1998. ''Betraying the Omaha Nation, 1790-1916'' Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806130910.</ref> |

| − | Fontenelle was elected principal chief of the tribe in 1853 when the United States was urging the Omahas to relinquish their land. In that role he negotiated the Treaty of 1854, selling nearly all of the Omaha land to the government except for the land comprising present-day [[Thurston County, Nebraska|Thurston County]], where a [[Indian reservation|reservation]] was established.<ref name=logan/ | + | Fontenelle was elected principal chief of the tribe in 1853 when the United States was urging the Omahas to relinquish their land. In that role he negotiated the Treaty of 1854, selling nearly all of the Omaha land to the government except for the land comprising present-day [[Thurston County, Nebraska|Thurston County]], where a [[Indian reservation|reservation]] was established.<ref name=logan/> Soon after Fontenelle was killed in a skirmish with the [[Brule]] and [[Arapaho]]. Some regarded Logan Fontenelle as the "last great chief" of the Omaha.<ref>Waitley, Pat. [http://www.kancoll.org/books/andreas_ne/blackbird/blackbird-p1.html Blackbird County]. Andreas' History of Nebraska. Retrieved November 11, 2007.</ref> |

The Omaha never took up arms against the U.S., and several members of the tribe fought for the [[Union (American Civil War)|Union]] during the [[American Civil War]], as well as each subsequent war through today. By the 1870s, bison were fast disappearing from the plains and the Omaha had to increasingly rely upon the [[United States Government]] and its new culture. | The Omaha never took up arms against the U.S., and several members of the tribe fought for the [[Union (American Civil War)|Union]] during the [[American Civil War]], as well as each subsequent war through today. By the 1870s, bison were fast disappearing from the plains and the Omaha had to increasingly rely upon the [[United States Government]] and its new culture. | ||

| Line 60: | Line 60: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * Boughter, Judith A. 1998. ''Betraying the Omaha Nation, 1790-1916''. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. 978-0806130910 | + | * Boughter, Judith A. 1998. ''Betraying the Omaha Nation, 1790-1916''. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806130910. |

| − | * La Fleche, Francis | + | * La Fleche, Francis. 1978. ''The Middle Five: Indian Schoolboys of the Omaha''. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803279018. |

| − | * Fletcher, Alice | + | * Fletcher, Alice. 1896. ''Tribal Life Among the Omaha Indians''. ASIN B000W48Z6K. |

| − | * Mathews, John Joseph. 1982. ''The Osages: Children of the Middle Waters''. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806117706 | + | * Mathews, John Joseph. 1982. ''The Osages: Children of the Middle Waters''. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806117706. |

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | * | + | * [http://www.omahatribeofnebraska.com/ Main Page]. Omaha Tribe of Nebraska. Retrieved November 11, 2007. |

| − | + | * Irving, Washington. [http://www.xmission.com/~drudy/mtman/html/astoria/chap16.htm Washington Irving's Astoria]. Astoria or Anecdotes of an Enterprise Beyond the Rocky Mountains. Retrieved November 11, 2007. | |

| − | + | * [http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/lewisandclark/intro22.htm Lewis and Clark Historical Background]. National Park Service. Retrieved November 11, 2007. | |

| − | * | + | * Campbell, Paulette W. [http://www.neh.gov/news/humanities/2002-11/ancestralbones.html Ancestral Bones Reinterpreting the Past of the Omaha]. National Endowment for the Humanities. Retrieved November 11, 2007. |

| − | * | + | * [http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/omhhtml/omhhome.html Omaha Indian Music] American Memory at the Library of Congress. Retrieved November 11, 2007. |

| − | * | + | *[http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/DTTable?_bm=y&-context=dt&-ds_name=DEC_2000_SF1_U&-CHECK_SEARCH_RESULTS=N&-CONTEXT=dt&-mt_name=DEC_2000_SF1_U_P001&-tree_id=4001&-all_geo_types=N&-redoLog=true&-transpose=N&-_caller=geoselect&-geo_id=label&-geo_id=14000US19133940100&-geo_id=14000US31021940100&-geo_id=14000US31039940100&-geo_id=14000US31173940100&-geo_id=25000US2550&-search_results=25000US2550&-format=&-fully_or_partially=N&-_lang=en&-show_geoid=Y Omaha Reservation, Nebraska/Iowa] United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 11, 2007. |

| − | * [http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/omhhtml/omhhome.html Omaha Indian Music] American Memory at the Library of Congress Retrieved November | + | |

| − | *[http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/DTTable?_bm=y&-context=dt&-ds_name=DEC_2000_SF1_U&-CHECK_SEARCH_RESULTS=N&-CONTEXT=dt&-mt_name=DEC_2000_SF1_U_P001&-tree_id=4001&-all_geo_types=N&-redoLog=true&-transpose=N&-_caller=geoselect&-geo_id=label&-geo_id=14000US19133940100&-geo_id=14000US31021940100&-geo_id=14000US31039940100&-geo_id=14000US31173940100&-geo_id=25000US2550&-search_results=25000US2550&-format=&-fully_or_partially=N&-_lang=en&-show_geoid=Y Omaha Reservation, Nebraska/Iowa] United States Census Bureau | ||

{{credits|Omaha|144737480}} | {{credits|Omaha|144737480}} | ||

Revision as of 02:55, 11 November 2007

| Omaha |

|---|

| Total population |

| 6,000 |

| Regions with significant populations |

| United States (Nebraska) |

| Languages |

| English, Omaha |

| Religions |

| Christianity, other |

| Related ethnic groups |

| other Siouan peoples |

The Omaha tribe is a Native American tribe that currently reside in northeastern Nebraska and western Iowa, United States. The Omaha Indian Reservation lies primarily in the southern part of Thurston County and northeastern Cuming County, Nebraska, but small parts extend into the northeast corner of Burt County and across the Missouri River into Monona County, Iowa. Its total land area is 796.355 km² (307.474 sq mi) and a population of 5,194 was recorded in the 2000 census. Its largest community is Pender.

During the late 1700s and early 1800s, the Omaha were briefly the most powerful Indians on the Great Plains. The tribe was the first in that region to master equestrianism, and developed an extensive trade network with early white explorers and voyageurs. Never known to take up arms against the U.S., members of the tribe assisted the U.S. during the American Civil War.

Omaha, Nebraska, the largest city in Nebraska, is named after them.

Language

The Omaha speak a Siouan language which is very similar to that spoken by the Ponca, who were once a part of the Omaha before splitting off into a separate tribe in the mid 1700s.

History

The Omaha tribe began as a larger woodland tribe comprising both the Omaha and Quapaw tribes. This original tribe inhabited the area near the Ohio and Wabash rivers around the year 1700.

As the tribe migrated west it split into what became the Omaha tribe and the Quapaw tribe. The Quapaw settled in what is now Arkansas and the Omaha tribe, known as U-Mo'n-Ho'n ("Dwellers on the Bluff").[1] settled near the Missouri River in what is now northwestern Iowa. Conflict with the Sioux and the splitting off of part of the tribe into the Ponca, forced the Omaha tribe to retreat to an area around Bow Creek in northeastern Nebraska in 1775, settling near present day Homer, Nebraska.

French fur trappers found the Omaha on the eastern side of the Missouri River in the mid-1700s. The Omaha were believed to have ranged from the Cheyenne River in South Dakota to the Platte River in Nebraska. Lewis and Clark found the tribe on the western side of the Missouri south of present-day Sioux City, Iowa in 1804.

Chief Blackbird was the leader of the Omaha from the late 1770s until his death during a smallpox epidemic in 1800. Under his leadership, the tribe became the most powerful in the region. Chief Blackbird established trade with the Spanish and French and used trade as a security measure to protect his people. The Omaha became the first tribe to master equestrianism on the Great Plains, which gave them a temporary superiority over the Sioux and other larger tribes as far as hunting and movement. Aware they traditionally had a lack of a large population to protect themselves from neighboring tribes, Chief Blackbird believed that fostering good relations with white explorers and trading were the keys to their survival. The village of Tonwantongo was home to Chief Blackbird and another 1,100 people around the year 1795. The Spanish built a fort nearby and traded regularly with the Omaha during this period. In 1800, a smallpox epidemic killed Chief Blackbird and at least 400 more residents in Tonwantongo. When Lewis and Clark visited Tonwantongo in 1804, most of the inhabitants were gone on a buffalo hunt and they ended up meeting with the Oto indians instead, however they were led to Chief Blackbird's gravesite before they continued on their expedition west.

Omaha villages were established and lasted from 8 to 15 years. Eventually, disease and Sioux aggression forced the tribe to move south. Villages were established near what is now Bellevue, Nebraska and along Papillion Creek between 1819 and 1856.

Loss of land

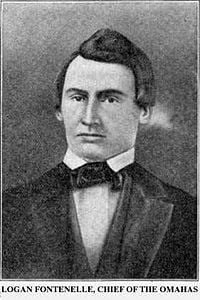

Logan Fontenelle, also known as Shon-ga-ska or Chief White Horse, (1825–July 16, 1855), was a mixed blood Omaha tribal leader who rose from obscurity to become chief. For several years, he also served as an interpreter for the United States government.[2] Fontenelle was present in August 1846 when the Omahas signed a treaty with Brigham Young allowing the Mormon pioneers to create Cutler's Park settlement on Omaha territorial lands.[3]

Fontenelle was elected principal chief of the tribe in 1853 when the United States was urging the Omahas to relinquish their land. In that role he negotiated the Treaty of 1854, selling nearly all of the Omaha land to the government except for the land comprising present-day Thurston County, where a reservation was established.[2] Soon after Fontenelle was killed in a skirmish with the Brule and Arapaho. Some regarded Logan Fontenelle as the "last great chief" of the Omaha.[4]

The Omaha never took up arms against the U.S., and several members of the tribe fought for the Union during the American Civil War, as well as each subsequent war through today. By the 1870s, bison were fast disappearing from the plains and the Omaha had to increasingly rely upon the United States Government and its new culture.

Joseph LaFlesche (ca 1820-1888), also known as E-sta-mah-za or Iron Eye, was the last recognized chief according to the old rituals of the Omaha tribe. He was the son of the French fur trader Joseph LaFlesche and his Ponca Indian wife. Iron Eye became the adopted son of Chief Big Elk of the Omaha; Big Elk personally selected him as his successor for chief. Iron Eye believed that his people's future lay in education and assimilation, including the adoption of the white man's agriculture and in accepting Christianity. This was met with some resistance among members of the tribe. He was a strong influence on his children, among them the Native American activists Susette LaFlesche Tibbles and Francis LaFlesche, and physician Susan La Flesche Picotte. Although these siblings disagreed about political and economic issues, all of them worked for the improvement of the quality of life for Native Americans and particularly for the Omaha tribe in Nebraska.

Culture

In pre-settlement times, the Omaha had a very intricately developed social structure that was closely tied to the people's concept of an inseparable union between sky and earth. This union was viewed as critical to perpetuation of all living forms and pervaded Omaha culture. The tribe was divided into two moieties, Sky and Earth people. Sky people were responsible for the tribe's spiritual needs and Earth people for the tribe's physical welfare. Each moiety was composed of five clans.

Omaha beliefs were symbolized in their dwelling structures. During most of the year Omaha Indians lived in earth lodges, ingenious structures with a timber frame and a thick soil covering. At the center of the lodge was a fireplace that recalled their creation myth. The earthlodge entrance faced east, to catch the rising sun and remind the people of their origin and migration upriver. The circular layout of tribal villages reflected the tribe's beliefs. Sky people lived in the north half of the village, the area that symbolized the heavens. Earth people lived in the south half which represented the earth. Within each half of the village, individual clans were carefully located based on their member's tribal duties and relationship to other clans. Earth lodges were as large as 60 feet in diameter and might hold several families, even their horses.

As the tribe migrated westward from the Ohio River region, the woodland custom of bark lodges was replaced with tipis (borrowed from the Sioux) and earth lodges (borrowed from the Pawnee). Tipis were used primarily during buffalo hunts and when relocating from one village area to another. They would sleep in lodges during the winter.

Contemporary Omaha

The Omaha Reservation today is located in northeastern Nebraska, approximately 26 miles southeast of Sioux City, Iowa, and severnty miles north of Omaha, Nebraska. The Missouri River is considered the eastern boundary of the reservation. The northern side borders the Winnebago Reservation, and over 93% within the reservation boundaries are owned by the Tribe and by Tribal members. The Omaha Tribal homelands total 2,594 square miles, throughout the counties of Thurston, Burt, Cuming, Wayne in Nebraska, and Monona County in Iowa. The national headquarters for the Omaha Tribe of Nebraska is located in Macy, Nebraska. The maintenance of the land, and the protection of the natural inhabitants is extremely important to the Omaha people, and they pride themselves on the preservation of their heritage for future generations.

Notes

- ↑ Mathews, John Joseph. 1961. The Osages: Children of the Middle Waters. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Logan Fontenelle. Nebraska Department of Education. Retrieved November 11, 2007.

- ↑ Boughter, Judith A. 1998. Betraying the Omaha Nation, 1790-1916 Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806130910.

- ↑ Waitley, Pat. Blackbird County. Andreas' History of Nebraska. Retrieved November 11, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boughter, Judith A. 1998. Betraying the Omaha Nation, 1790-1916. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806130910.

- La Fleche, Francis. 1978. The Middle Five: Indian Schoolboys of the Omaha. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803279018.

- Fletcher, Alice. 1896. Tribal Life Among the Omaha Indians. ASIN B000W48Z6K.

- Mathews, John Joseph. 1982. The Osages: Children of the Middle Waters. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806117706.

External links

- Main Page. Omaha Tribe of Nebraska. Retrieved November 11, 2007.

- Irving, Washington. Washington Irving's Astoria. Astoria or Anecdotes of an Enterprise Beyond the Rocky Mountains. Retrieved November 11, 2007.

- Lewis and Clark Historical Background. National Park Service. Retrieved November 11, 2007.

- Campbell, Paulette W. Ancestral Bones Reinterpreting the Past of the Omaha. National Endowment for the Humanities. Retrieved November 11, 2007.

- Omaha Indian Music American Memory at the Library of Congress. Retrieved November 11, 2007.

- Omaha Reservation, Nebraska/Iowa United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 11, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.